If you’re a college student, you have probably encountered various loaded terms and accusations directed at Israel. You might find it difficult to refute or engage in discussions about such broad claims about the Jewish state. Below we will break down some common myths about Israel.

“Israel is committing genocide against Palestinians.”

Today, the word “‘genocide”’ is unfortunately used casually, so it is important to understand what this word actually means.

Genocide refers to the deliberate and systematic killing of a group of people with the intent of eradicating them due to their ethnicity, nationality, religion or race.

Past genocides include the Holocaust, where 6 million Jews were systematically murdered, the Rwandan Genocide, where over 600,000 Tutsis were killed by Hutu militias, and the Darfur Genocide, where 300,000 civilians were murdered.

While the number of Palestinians and Israelis who have been killed is tragic, it is one of the grim realities of war.

The IDF, unlike any other army, goes to great lengths to minimize civilian casualties. In the current war, this includes issuing warnings and distributing leaflets in Gaza to advise residents to evacuate, even if it goes against their military strategy.

IDF releases an audio recording of an officer in the Military Intelligence Directorate's Unit 504 — which specializes in HUMINT — speaking to a Gazan man, during which he describes how Hamas is preventing people from evacuating from the northern part of the Gaza Strip. pic.twitter.com/VgMJO3SzVo

— Emanuel (Mannie) Fabian (@manniefabian) October 26, 2023

Minimizing civilian casualties is a core principle in the IDF’s code of ethics known as tohar ha’neshek, “purity of arms.”

Read more: Is Israel doing enough to protect Palestinian civilians in Gaza?

While the IDF aims to minimize civilian casualties, Hamas intentionally uses its citizens as human shields, significantly influencing the death toll and public perception of the conflict.

Hamas stores rockets and weapons in homes and schools, with many tunnel entrances located in or near civilian infrastructure.

Who stores RPG missiles, anti-tank missiles, explosive devices, long-range missiles, grenades and UAVs at a school and a medical facility in Gaza?

— Israel Defense Forces (@IDF) December 6, 2023

The answer: Hamas.

Hamas doesn’t hide their terrorism. Stop excusing it. pic.twitter.com/az4Es0Vh5v

A 2019 NATO report explained Hamas’s strategy of using human shields: “If the IDF uses lethal force and causes an increase in civilian casualties, Hamas…can accuse Israel of committing war crimes, which could result in the imposition of a wide array of sanctions.”

The claim that Israel is committing genocide against Palestinians is contradicted by demographic data as well. Typically, genocides result in a significant decline in the targeted population. However, the Palestinian population has doubled 10 times since 1948, when Israel was first accused of committing genocide against Palestinians.

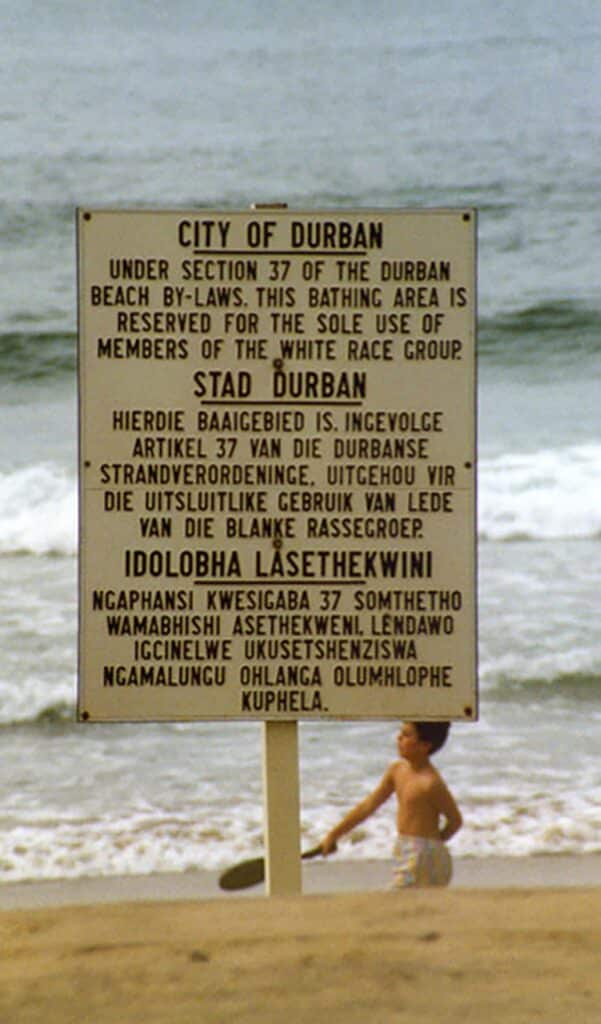

“Israel is an apartheid state.”

The term “apartheid” originates from the system of institutionalized racial segregation and discrimination. It involves state-sanctioned, racially based laws that deny certain groups equal rights, like access to the same living spaces and education opportunities.

Accusations of apartheid against Israel often cite unequal rights for Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank compared to Israeli citizens. However, this comparison overlooks the fact that Palestinians in these areas are not Israeli citizens.

In Israel, all citizens, including over 2 million Arab citizens, have equal rights under the law. Under an apartheid system, those 2 million Arab citizens of Israel would have different rights from their Jewish counterparts.

While there are indeed disparities between Arab and Jewish Israelis, such as socioeconomic gaps, it’s important to note that such disparities exist in most countries. However, these disparities differ significantly from apartheid.

As the only democracy in the Middle East, Israel’s commitment to equal rights is enshrined in the Principle of Equality, which guarantees social and political rights for all citizens, regardless of religion, race, or gender.

Arab citizens hold positions as Supreme Court judges, government ministers, military officers, and business leaders. An Islamist party was a part of the previous Israeli government coalition, showing how Arab citizens take part in every corner of Israeli society.

Michael Koplow points out that the use of the term “apartheid” “rests squarely on the concept of racial domination.” Yet, the Israeli system includes citizens from diverse racial backgrounds, even in the highest offices of government.

The reason Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank don’t have the same rights as Israelis is because they are not Israeli citizens. It’s worth noting that by international law, countries have an obligation to prioritize their own citizens, and this is not unique to Israel.

Proponents of the “apartheid” claim often cite Israel’s Law of Return, which grants all Jews the ability to gain Israeli citizenship.

However, similar laws exist in other countries, including Mexico, Finland, Greece, Poland, Germany, Italy and Denmark. These laws, allowing indigenous populations to return, are common aspects of national immigration policies and do not constitute apartheid.

“Israel is a settler colonial state.”

The label “settler-colonial” for Israel stems from the concept of settler colonialism, where a foreign power establishes settlements with the economic, cultural, or religious imposition on an indigenous population, often with the intent of displacement or elimination.

Zionism — the belief that Jews have the right to self-determination in the land of Israel — diverges from the classic model of settler colonialism for many reasons.

Read more: What is Zionism? 6 different types of Zionist thinking

First, the Jewish immigrants who arrived in Palestine before the establishment of the State of Israel were largely refugees fleeing persecution. Unlike the typical settler colonial narrative, their migration to Palestine did not involve state-sponsored expansionism.

Second, the intent to displace or transfer Arabs living on the land was fringe and isolated. Theodore Herzl, the father of modern political Zionism, did not advocate for the displacement or transfer of Arab inhabitants.

In a letter, he emphasized the mutual prosperity of both Arab and Jewish inhabitants, stating, “Who would think of sending [Palestinian Arabs] away? It is their well-being, their individual wealth that we would increase in bringing our own.”

Lastly, characterizing Israel as a settler colony disregards the historical connection of Jews to the land of Judea, now Israel. Evidence, including the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Arch of Titus, attests to the ancient Jewish presence on the land and their lasting connection to it.

Even the term “Jew” is derived from Judea, underscoring these historical and deep religious ties. Accusing Israel of ”settler colonialism” devoid of a factual basis undermines the seriousness of the term. While there is legitimate criticism of the Israeli government, using loaded terms without historical support distorts the narrative and delegitimizes Israel’s historical ties to the land.

“Israel is an occupying power”

“Occupation,” under international law, refers to a situation where a territory is under the authority of a hostile army, without the host state’s consent. This control doesn’t necessarily involve violence and can result from a show of force.

To understand whether Israel is “occupying” the West Bank and Gaza Strip, we need to start with how Israel initially gained control of these territories in 1967.

In May 1967, Arab forces lined up along Israel’s borders, openly threatening to annihilate the Jewish state. Outnumbered by these Arab armies and seeing this as an act of war, Israel responded with a preemptive strike.

Within six days, Israel pushed these armies back and gained control of the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, East Jerusalem, the Golan Heights, and the Sinai Peninsula. With this new territory, Israel tripled its size practically overnight.

Israelis saw this new territory as fairly won in a defensive war. However, the Arab world refused to recognize Israel’s gains in the war, setting the stage for decades of conflict that persist to this day.

With this historical context in mind, we can now consider the current situation. Israel does not occupy the Gaza Strip, which it unilaterally withdrew from in 2005.

While Israel and Egypt have maintained control over Gaza’s borders, airspace and maritime borders for security reasons, Israel does not govern or administer the Gaza Strip and did not have a presence there between 2005 and the current war.

In the West Bank, the issue is more complex. The Jewish people have had a continuous presence in the land of Israel — including in the West Bank — for thousands of years, making them native and indigenous to this land.

Judea and Samaria (commonly known as the West Bank) are deeply ingrained in Jewish history, religion and identity, with Jewish historical ties there dating back to ancient times.

So, while the land is deeply Jewish, the question of “occupying Palestinian people” is more nuanced. The Israeli presence in these areas reflects a complicated mix of security measures, administrative control, and cohabitation with Palestinian residents.

In his book “Catch 67: The Left, the Right, and the Legacy of the Six-Day War,” Micah Goodman captures the nuances of the situation:

“On the one hand, the territories are not stolen land that came under Israel’s control by immoral means, so they are not in themselves occupied. On the other…Israel imposes a military rule on a Palestinian population that has no say over the state’s decisions, so the Palestinians are a nation that lives under occupation. The conclusion is that the territories are not occupied, but the Palestinian people are.” (page 104)

This perspective reflects a critical distinction between the land itself — with its ancient Jewish connections and captured by Israel in a defensive war — and the complex realities of governing a Palestinian population in some parts of the West Bank.

For a deeper dive into the question, read Unpacked’s article, “Is Israel occupying the West Bank?”

“Israel expelled Palestinians in 1948”

The term “Nakba,” meaning “catastrophe” in Arabic, refers to the Palestinian perspective on Israel’s establishment on May 14, 1948.

Nearly 700,000 Palestinian Arabs either fled the area or were expelled before, during, or after Israel’s independence. So, what happened?

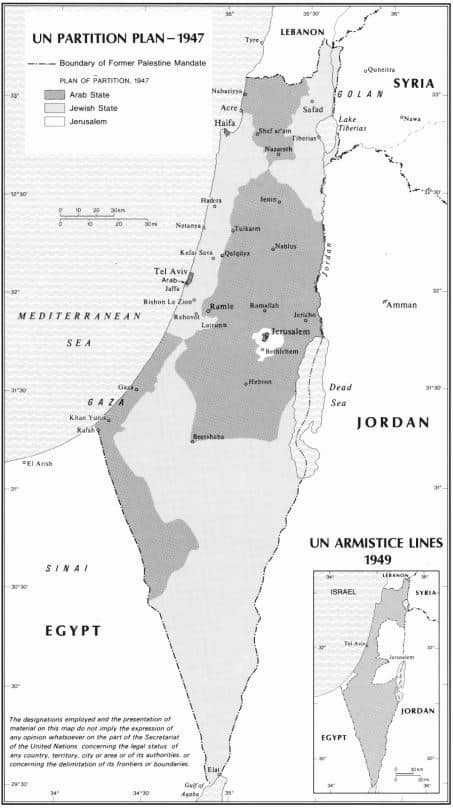

In 1947, the U.N. General Assembly adopted a Partition Plan, which called for both an independent Jewish and an Arab state in what was then British-controlled Mandatory Palestine.

Partition was hardly ideal for either people, as both states were left with vulnerabilities, separated territories, and Jerusalem — sacred to Jews, Muslims and Christians — designated as an international zone.

Ultimately, the Zionists accepted the plan, but Arab leaders rejected it and then launched a wave of terror attacks on Jews, attempting to undermine the hope for stability promised by the Partition Plan.

The Arab League, a coalition of surrounding Arab states, warned that partition would lead to “a war of annihilation.” Even in the face of these threats, on May 14, 1948, Israel’s provisional government declared an independent Jewish state in line with the Partition Plan.

The very next day, seven surrounding armies invaded the newly established Israel.

Many Palestinians left their homes, anticipating a quick Arab victory and planning to return once the conflict ended. However, Israel won the war and they didn’t return. Some Palestinians were instructed by Arab leaders to evacuate in order to make way for strategic military operations.

It is also acknowledged by historians like Anita Shapira that Israeli forces did expel portions of the Arab population.

At a meeting of the provisional government on June 16, 1948, Moshe Sharett (who would serve as Israel’s second prime minister, for one year) addressed the issue:

“Had any of us said that one day we must get up and expel them all — it would have been considered madness,” he said.

“But if it came about during the upheavals of war, a war declared on us by the Arab nation, and as the Arabs themselves were fleeing — then it is one of those revolutionary changes after which history does not return to the [earlier] status quo.”

Meanwhile, in nearly every neighboring Arab country, civilian mobs directed their rage at local Jews who supported Israel’s creation.

They committed waves of violence against Middle Eastern Jewish communities, some of whom had been there for thousands of years. About 850,000 Jews were forced out or relocated, and Israel absorbed nearly 700,000 of them. Learn more by listening to our “Unpacking Israeli History” episode below:

Israel, whose total population doubled after the war, refused to allow back the 700,000 Arabs, either for demographic reasons or because many supported the invading Arab armies.

It is also important to note that when a new state is founded, the unfortunate and sad reality is that displacement occurs. Take the founding of India in 1947, just one year prior to that of Israel, where nearly 20 million Muslims were displaced.

Despite Israel’s population having the highest percentage of Muslims outside of Muslim-majority countries, it has faced disproportionate scrutiny.

Since 1948, Palestinians have rejected multiple offers of statehood, hindering the possibility of their return through numerous proposed two-state solutions.

“Zionism is racism”

In 1975, the global perception of Zionism changed forever after the United Nations passed a resolution declaring that “Zionism is a form of racism and racial discrimination.”

The resolution labeled Zionism as racism without providing any reasoning or depth. It lacked substantiated arguments and failed to define its terms, making the accusation baseless and politically motivated.

Although this resolution was later repealed in 1991, it had negative consequences for Jews all around the world, labeling them as racist for simply believing in the right to return to their ancestral homeland. The resolution turned “Zionism” into an ugly word, one associated with white supremacy and discrimination.

While the claim that Zionism is a form of racism is commonly heard today, it is important to understand that Zionism is fundamentally not about racial superiority or discrimination.

At its core, Zionism embodies a multifaceted ideology that asserts the right of Jews to self-determination in their ancestral homeland. It is a national liberation movement similar to those that have sought to restore the rights and independence of other historically oppressed peoples around the world.

Read more: What is the definition of Zionism? 6 different types of Zionist thinking

Zionism’s roots extend far beyond the modern political movement initiated by Theodor Herzl in the late 19th century. It dates back thousands of years, starting with the biblical patriarch Abraham, and is deeply intertwined with Jewish history, culture and religious aspirations.

The longing for a return to Zion, the biblical name for Jerusalem, has been a central theme in Jewish prayers and rituals for millennia.

Moreover, Zionism also represents a cultural revival of the Jewish people, celebrating their rich heritage and contributing to the diversity of global cultures. It is about re-establishing a Jewish presence in a land where they have had a historical and continuous connection for over 3,000 years.

To equate Zionism with racism is to misunderstand its true nature and objectives. It is a misrepresentation that ignores the legitimate aspirations of the Jewish people for self-determination and the restoration of their historical ties to their homeland.

For more history and context surrounding the current Israel-Hamas war, visit our Israel at War page.

Originally Published Jan 8, 2024 08:45PM EST