Editor’s note: This article is part 1 of a three-part series on Israel’s presence in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Read parts 2 and 3 on whether Israel is occupying the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

The Six-Day War of 1967 was a pivotal moment in Israel’s history, dramatically changing the region’s geopolitical landscape.

In May 1967, Arab forces lined up along Israel’s borders, openly threatening to annihilate the Jewish state.

“The armies of Egypt, Jordan, Syria and Lebanon are poised on the borders of Israel…This act will astound the world,” Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser declared the day before the war. “Today they will know that the Arabs were arranged for battle; the crucial hour has arrived.”

Outnumbered by these Arab armies and seeing this as an act of war, Israel responded with a preemptive strike.

Within six days, Israel pushed these armies back and gained control of the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, East Jerusalem, the Golan Heights, and the Sinai Peninsula. With this new territory, Israel tripled its size practically overnight.

However, the Arab world refused to recognize Israel’s gains in the war, setting the stage for decades of conflict that persist to this day. Understanding this historical background is essential for understanding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict today.

Here’s how Israel initially gained control of the West Bank and Gaza in 1967 and how the Arab world responded.

The Jewish connection to the land

The Jewish people have had a continuous presence in the land of Israel — including Judea and Samaria (commonly known as the West Bank) and Gaza — for thousands of years, making them native and indigenous to this land.

This bond is not solely historical; it’s deeply embedded in Jewish culture, literature and religion. Jerusalem is mentioned over 600 times in the Tanakh, the Hebrew Bible, and is a focal point of daily and holiday prayers.

Jewish traditions and the Hebrew calendar, with holidays like Passover, Shavuot, and Sukkot, are intimately tied to the land’s agricultural cycles, reflecting a profound bond with their ancestral homeland. This land isn’t just an ancient birthplace; it’s integral to Jewish identity.

How Israel gained control of the territories in 1967

From the moment the British expressed support for the creation of a Jewish state with the Balfour Declaration in 1917 up until Israel’s establishment in 1948, many Jews began pushing for a Jewish return to the land, which was then British Mandate Palestine. Tensions between Jews, Arabs, and British forces increased.

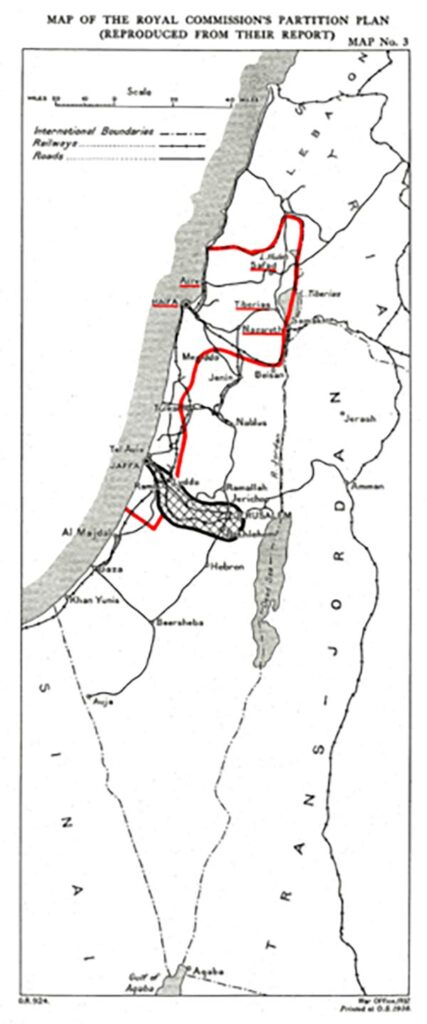

In the 1930s, the British created the Peel Commission to propose a solution to the land conflict

between the Jews and the Arabs. It was the first official attempt to divide the land into two states.

In 1937, the Peel Commission proposed that the British allocate 75% of the land to the Arabs and roughly 25% to the Jews, with the British government controlling Jerusalem.

Jewish leadership was pretty divided in opinion but ultimately, they accepted the proposal, but the Arab leadership, led by Amin al-Husseini, immediately rejected it.

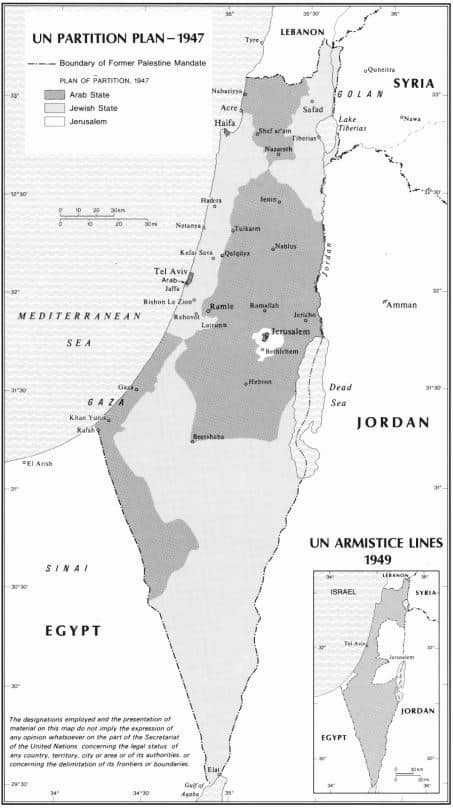

After years of violence and Britain’s relinquishing control, the U.N. proposed the 1947 Partition Plan for a Jewish and Arab state, with Jerusalem under international governance.

The plan — Resolution 181 — was extremely detailed, as you can see in the map below.

Partition was hardly ideal for either people, as both states were left with vulnerabilities, separated territories, and Jerusalem — sacred to Jews, Muslims and Christians — designated as an international zone.

Once again, Jewish leaders were conflicted about the partition proposal.

“Supporters saw it as the seed of an independent Jewish state, while for opponents it meant giving up the vision of the historical Land of Israel,” historian Anita Shapira explained in her book “Israel: A History” (p. 85).

Others opposed the plan for practical reasons, arguing that the partitioned Jewish state “would be unable to sustain itself and to absorb and be a refuge for masses of Jews,” Shapira wrote.

But the proposal presented a real hope for Jewish sovereignty. Ultimately, the Zionists — led by David Ben-Gurion and Chaim Weizmann — accepted the plan. When faced with the best offer they’d gotten in millennia, they were not going to pass it up.

By contrast, the Arab leaders were united in their opposition to the plan. They opposed any territorial division that would give the Jewish people a homeland.

They also argued that the international community did not have a right to divide up land that the Arabs considered rightfully theirs.

To learn more about the 1947 Partition Plan, listen to our “Unpacking Israeli History” episode on this topic:

Arabs launched a new wave of terror attacks on Jews, attempting to undermine the hope for stability promised by the Partition Plan.

Pan-Arabism reached a fever pitch, and the head of the Arab League, a coalition of surrounding Arab states, warned that partition would lead to “a war of annihilation.”

Even in the face of these threats, on May 14, 1948, Israel’s provisional government declared an independent Jewish state in line with the Partition Plan.

The next morning, seven surrounding armies invaded newborn Israel.

At the end of the war in 1949, Israel signed armistice agreements with Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan, and Syria, establishing the borders and lines we recognize today.

As part of these agreements, Jordan occupied and later annexed the West Bank and East Jerusalem, while Egypt took control of the Gaza Strip.

From 1949-1967, over 500 Israelis were killed in attacks by Palestinian groups called “Fedayeen,” as well as in clashes with Egyptian forces during the Suez Crisis.

In 1967, leading up to the Six-Day War, Syrian, Jordanian and Egyptian forces gathered near Israel’s borders, openly threatening to annihilate the Jewish state and cutting off Israel’s access to the Suez Canal, a red line for Israel. The Arab forces on Israel’s borders greatly outnumbered the Jewish state’s military.

Israel responded with a preemptive strike against Egypt’s air force. It also sent a message to Jordan urging them not to join the conflict.

However, Jordan disregarded this warning and attacked Israel, prompting Israel to respond. Syria also engaged in the conflict shortly after.

Within six days, Israel pushed these armies back and gained control of East Jerusalem, the West Bank, the Golan Heights, the Gaza Strip, and the Sinai Peninsula. With this new territory, Israel tripled its size practically overnight.

It was after this war that the term “occupation” became commonly used in reference to Israel’s control of the West Bank, Gaza (which Israel withdrew from in 2005), and the Golan Heights.

However, this term disregards the ancient and ongoing Jewish connection to the land and the complex history that led to Israel’s current boundaries. Let’s explore what happened next.

The aftermath of the Six-Day War

Israel’s capture of East Jerusalem, the West Bank, the Golan Heights, the Gaza Strip, and the Sinai Peninsula created intense resentment in the region, with Palestinians referring to the war as the “Naksa,” the setback.

Three months after the Six-Day War, Arab leaders declared their “Three No’s”: “No peace with Israel, no recognition of Israel, and no negotiations with Israel.” In their eyes, Israel’s newly acquired lands didn’t really belong to Israel.

Two months later, the U.N. Security Council passed Resolution 242 asserting “the inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by war.” The council demanded that Israel withdraw from territories it captured in the Six-Day War.

This period also marked a pivotal shift in the Arab League’s approach toward the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Prior to the war, the focus of Arab nations was primarily on broader regional disputes with Israel rather than the specific pursuit of a Palestinian state.

However, after Israel’s gains in the Six-Day War, the Arab League began to increasingly advocate for the establishment of an independent Palestinian state — marking a departure from the previous focus on Egyptian and Jordanian control over these territories.

This shift signified the rise of the Palestinian national movement — which officially emerged in 1964 with the establishment of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) — as a central issue in the Arab-Israeli conflict.

In 1974, the Arab League declared that the PLO would be the sole representative of the Palestinian people in any land that was “liberated” from Israeli control. This endorsement significantly boosted the PLO’s status and role in the Palestinian national movement.

Jordan, which initially sought to incorporate the West Bank, officially relinquished its claim to the territory in 1988, acknowledging the PLO’s role.

With respect to Jerusalem, Arab leaders believed it belonged to them due to the deep significance of Jerusalem for Muslims and the fact that an Arab population had lived there for centuries.

Palestinian Arabs viewed Israel as wrongly “occupying” the city, with all Palestinian leaders in the years since insisting that East Jerusalem be part of any future Palestinian state.

But many Israelis disagreed. For them, the Jewish state had fairly won control of East Jerusalem and the other territories in a defensive war.

Watch our Today Unpacked video to learn more about the debate over Jerusalem:

This dispute over Jerusalem, regarded as sacred by both Jews and Muslims, remains unresolved, with both sides claiming rights to the city. Of course, many within those populations believe that the sacred city can be shared, but others disagree.

Conclusion

The ramifications of the Six-Day War continue to resonate in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict today. The war not only altered the geopolitical landscape of the Middle East but also significantly shaped the narrative and perceptions surrounding the conflict.

The territorial gains made by Israel in 1967 and the subsequent responses from the Arab world and the international community have become focal points in the ongoing debate over sovereignty.

The rejection of these gains by Arab nations, the rise of the Palestinian national movement, and the dispute over Jerusalem and these territories have entrenched positions on both sides.

The Six-Day War was not just a turning point in the history of Israel and its neighboring countries; it was a catalyst that reshaped the dynamics of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The war’s aftermath has defined the contours of peace negotiations, diplomatic discourse, and the struggle for self-determination that persist to this day.

Read more:

Originally Published Dec 6, 2023 04:47PM EST