One of the themes of this podcast is that Israeli history doesn’t begin with Ben-Gurion’s Declaration of Independence in 1948. Seriously, look at our archive. One-third of our episodes cover events before 1948. That’s by design. Because – as I constantly remind you – the story of Israel is the story of a modern state in an ancient land.

And yet, we’ve never actually talked about Israel’s first moments as a state. About the six months between the UN Partition Plan – when the world officially carved out a sliver of real estate that the Jews could call their own – and the Declaration of Independence, when that Jewish state shifted from promise to reality.

I can’t think of a better time to tell that thrilling, painful, bloody, miraculous story than the lead-up to Israel’s 75th birthday. So for the next three weeks, we’re going to do something different. Consider the next three episodes as one long story, told in mostly chronological order. We won’t skip around. We won’t recap at the end with five fast facts. I’m not going to share what I find to be enduring lessons, or even a letter from a listener. Until we reach the last chapter, we’re telling one story that starts with the UN vote to officially partition Palestine and ends with the moment Ben-Gurion declared hakamat medina yehudit b’Eretz Yisrael, hee Medinat Yisrael. The establishment of a Jewish state in the Land of Israel, the State of Israel. It’s a story in three parts, triumphant and tragic in turn. A story of war. A story of sacrifice. And ultimately, a story of liberation – the final chapter of which we’ll recount on the 75th anniversary of Ben-Gurion’s declaration.

This isn’t the start of Israeli history. But it is where the State of Israel officially begins.

David Ben-Gurion knew that war was coming.

It had been bubbling around the edges of everyday life for some time now. Sporadic Arab attacks on Jewish communities. Reprisals from the hardline Jewish paramilitaries. Mixed signals from the Brits, who seemed entirely ready to wash their hands of this fractured land and its fractious inhabitants. Occasional tensions between the three Jewish paramilitaries, whose different approaches often had them butting heads. In short: the Yishuv was ready to ignite. (And yes, we’ve talked about all of these things before – check out the show notes for a refresher.)

The only question was what kind of fight it would be. Would the Yishuv face its first real war as a self-determining country with an organized army? Or would the world decide that there would be no Jewish state, leaving the Yishuv at the mercy of Arabs both within and outside of Palestine?

On November 29, 1947, delegates from around the world gathered in Long Island, New York, to answer that question. (Side note: not what I think about when I think about Long Island.) Here it was, at last, the result of so many years of planning and praying and hoping, of fighting and dying and defying. Finally, the UN would decide whether to split the area known as Palestine into two states: one for Arabs, one for Jews, with Jerusalem under international control.

As the delegates half a world away voted on the future of Palestine, the land’s inhabitants – Jews and Arabs alike – huddled around their radios, stomachs churning with anxiety or excitement, each acutely conscious that this was it. Jews around the world prayed that the world would recognize the right of a stateless minority to return to its ancestral homeland. Meanwhile, most Arabs hoped – with equal fervor – that the world would end this foolish Zionist gambit once and for all. All they needed was a two-thirds majority in either direction, and then the Jews would either have a state, or they wouldn’t.

Imagine the tension. In living rooms, in government buildings, in cafes, on the streets: everyone was glued to a radio as the faraway voice of Oswaldo Aranha, the President of the UN General Assembly, read out the votes. Nerd corner alert: there’s a reason several streets in Israel are named after this guy. Though he wasn’t Jewish, Aranha was a staunch Zionist. So when he suspected that the Zionists wouldn’t have enough votes to achieve the two-state solution, he asked his allies in the UN to delay the vote by giving extra-long speeches – that’s nuts! With the vote delayed, the Zionist camp was able to lobby hard, ultimately gaining the majority needed to officially partition Palestine. So he must have been pretty satisfied as he read out the names of the countries who had just created the world’s newest states:

“Afghanistan, no. Argentina, abstention. Australia, yes…” All the way through “Venezuela, yes. Yemen, no. Yugoslavia, abstain. The resolution of the committee on Palestine was adopted by 33 votes, 13 against, ten abstentions.”

The UN General Assembly erupted in applause – but it was nothing compared to the Yishuv’s celebration. Jewish people dancing, crying, clapping, lighting bonfires, waving flags. Hoisting each other aloft, as though at a wedding.

The Israeli author Amos Oz later recalled the night of the UN vote. He was eight years old, living in Jerusalem, which would soon be, in his words, “besieged, shelled, starved, the water supply cut off.” But that night, as Aranha tallied the votes over crackling radio waves, Oz’s father Arieh crawled into bed with him. Both of Oz’s parents were refugees from Europe, with relatives who had not made it out in time. And so both knew exactly what this vote meant for the Jewish people. Holding his son tight, Arieh explained: “From now on, from the moment we have our own state, you will never be bullied just because you are a Jew. Not that. Never again. From tonight that’s finished. Forever.” Oz later said this was the only time he ever saw his father cry.

Similar scenes played out all over the future state. Parents hugging children who would never know the fury of a pogrom. Partisans who had fought in the forests of Europe, tears in their eyes. Children who had spent years hidden in attics and basements, now free to grow up strong and proud in the open air. Immigrants who had braved rickety boats and choppy seas, just to sneak onto Palestine’s shore under cover of darkness. And from a balcony in Jerusalem, future prime minister Golda Meir addressed the throng: “For two thousand years we have waited for our deliverance. Now that it is here, it is so great and wonderful that it surpasses human words. Jews, mazel tov.”

From a balcony in Jerusalem, future prime minister Golda Meir addressed the throng: “For two thousand years we have waited for our deliverance. Now that it is here, it is so great and wonderful that it surpasses human words. Jews, mazel tov.”

I get choked up hearing those words. Jews, mazel tov.

It wasn’t just the Jews of Palestine she was talking to. This vote was a sea change for world Jewry. Sure, it’s hard to predict the future – would diaspora Jews leave their comfortable lives in America or Argentina or Australia for a tiny and soon-to-be-embattled Jewish state? But at least now they would have the option, in the not-unimaginable event that their lives abroad ever became less than comfortable.

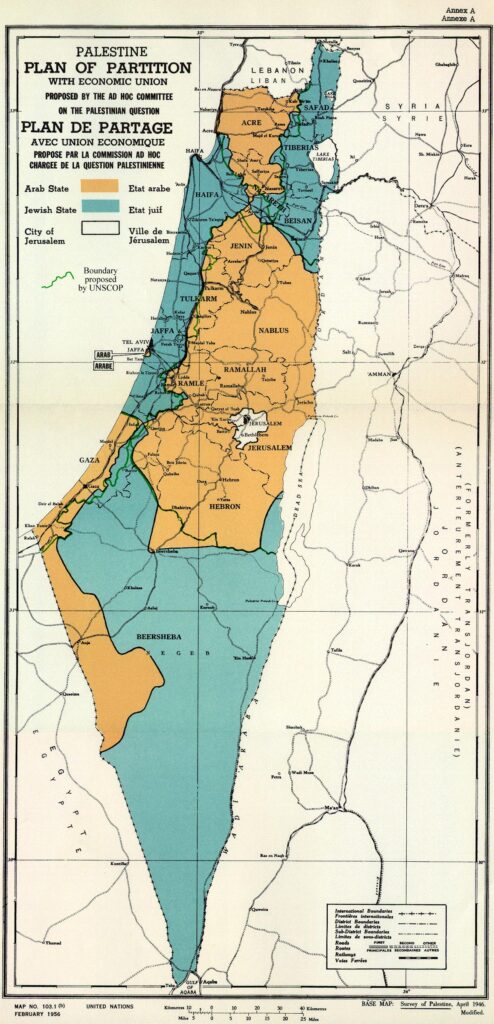

Remember, the UN had just carved out two separate states from tiny Palestine: one for Jews, comprising the holy cities of Tzfat and Tiberias in the north, the coastal cities of Haifa and Tel Aviv in the west, and the Negev desert to the south. The Arab state would include the northern cities of Akko and Nazareth, the region we now know as the West Bank, plus a portion of what we now think of as central Israel, and the coastline of the Gaza strip. Jerusalem – that fraught and sacred city – would be placed under international control.

Was this exactly what the Jews had been waiting for? No. It wasn’t. This plan carved up the land clumsily, turning the spiritual and national capital of the Jewish people into international property. Certainly, Revisionist Zionists, who believed that Israel should include even the East Bank of the Jordan River, were less than thrilled. But it was a state. A tiny, flawed, vulnerable state where the Jewish people could finally be free. And so the streets teemed with celebration.

But not everyone was celebrating. David Ben-Gurion wrote later, “I could not dance, I could not sing that night. I looked at them so happy, dancing, and I could only think that they were all going to war.” He was right, even if most of the Yishuv wouldn’t realize it for weeks. For most of the Arab world, state-building was a zero-sum game. Two states meant that they had lost. But Palestine’s Arabs weren’t going down without a fight. And soon, volunteers from across the Arab world would join them.

By 8:20 the next morning, Arabs in Jaffa and Jerusalem and Haifa began to mobilize. A group of eight Arabs ambushed one bus, then another. Throughout the day, snipers shot into Jewish neighborhoods. All told, at least eight Jews died that day – the first casualties of a war that would ultimately cost the nascent state 1% of its population.

A day after these attacks, the Arab Higher Committee in Cairo called for a three-day Arab strike in Palestine – which ended up being accompanied by riots, lootings, and destruction of Jewish property. Jerusalem’s streets boiled and seethed. The British, who had administered Palestine since 1922, stood by, some even participating in the looting, as the Haganah tried desperately to defend its community.

Civil war had come to Palestine.

In previous episodes, we’ve alluded to the war that Israelis call Milhemet HaShichrur, or The War of Liberation, and Palestinians call al-Nakbah, the catastrophe. And the way we’ve always described it, is that the day after Ben-Gurion declared independence, five – or six, or seven, depending on how you count them – Arab armies attacked the newborn Jewish state. The IDF fended them off, Israel emerged with a lot more territory than it had originally been allotted in the partition plan, Egypt took Gaza, Jordan took the West Bank, and the tiny Jewish state proved its mettle against its much bigger neighbors.

And to be clear, all of that is true. But that’s not the whole story. THERE IS A WHOLE STORY BEFORE THAT WHOLE STORY.

Before the Declaration of Independence on May 14, 1948, before the invasion of the Jewish state by multiple Arab armies on May 15th, Palestine would buckle and convulse under a wave of violence that few at the time recognized for what it was: the opening act of a war. Sounds ridiculous, right? How can you not know you’re at war? Turns out, pretty easily, when you live in one of the most contentious places on earth. Seriously. It sounds dark, but sporadic outbreaks of violence were – and still are – more or less status quo in the region.

The Yishuv caught on soon enough that something bigger was happening here. Because for the first few months after that fateful UN vote, Palestine’s Jews found themselves constantly on the defensive. The general pattern went something like this, though of course, different people, with different viewpoints, would portray the order of events a little differently. An Arab group would attack. Jews would fight them off. People on both sides would die, sometimes in horrific ways. All while the British – who knew that their days in Palestine were numbered – tried and failed to maintain their neutrality.

In classic British fashion, the British High Commissioner – and no, I don’t know exactly what that is, but I know it’s important – insisted that the British withdrawal would be organized, leaving Palestine in a ship-shape state. Very British, right?

But the British High Commissioner was fighting a losing battle. Because as you know from previous episodes of this podcast – again, check the show notes – the situation in Palestine had spiraled out of British control. They’d seen massacres and riots and strikes and a general Arab revolt. They’d been sabotaged and subverted by the Haganah, shot at and bombed by the Irgun and Lehi. And now, they were exiting a country that didn’t technically yet exist but had just exploded into war. So it’s not exactly a surprise that “law and order” was thin on the ground.

Complicating the whole messy situation was a general inconsistency towards both sides. Officially, the Brits were supposed to defend themselves and protect anyone who was being attacked, which, for the first few months of the war, mostly meant Jews. So it’s true that British soldiers did come to the aid of the vulnerable convoys that supplied Jewish Jerusalem. But they also handed over Jewish fighters to the so-called “justice” of Arab mobs – a “justice” that included lynching, mutilation, and death. And while the Haganah’s official policy was restraint and defense, the hardline paramilitaries had no such compunction. The Irgun and Lehi repaid the British in full for every drop of Jewish blood they spilled – which, in turn, made the Brits all the more likely to make life difficult for the Jews. And that’s to say nothing of their attacks on local Arabs.

Yeah, it was a mess. So let me make it as simple as I can, before I introduce a whole new layer of complexity. For the first few months of the war – which, at first, few recognized for what it was – Palestine’s Arabs went on the offensive, while the Jews played defense and the British backed whoever suited them at that moment. But we all know the end. The British leave. The Jews fend off multiple Arab armies. The Jewish people not only defend themselves, but emerge with more land than originally allotted to them by the partition plan. But a victory like that doesn’t come out of nowhere, and it certainly doesn’t come from a constant game of defense. So how did the Yishuv turn the tide?

As we’ve said many times before, the story of Israel is a story of beating the odds. But in November of 1947, Israel’s odds seemed pretty, pretty, pretty bad. Still, it was no accident that Israel emerged bloody but victorious in 1948. Because as we said at the start of this episode, David Ben-Gurion knew that war was coming. Back in 1946, he’d warned the delegates at the 22nd Zionist Congress that “The Land of Israel is surrounded by independent Arab states that have the right to purchase and produce arms, to set up armies and train them… there is danger that the neighboring Arab states will send their armies to attack and destroy the Yishuv.” In other words, sure, constant low level attacks are a pain. But I’m a lot more stressed about being flattened by Jordan, Egypt, and Syria. Ben-Gurion was not the sort of guy who sat by while the fate of his unborn country was at stake. It was he who reorganized the Haganah, helping it become, according to one British source, “the most powerful force in the Middle East, apart from the British Army.” (A good number of the Haganah’s fighters were in fact veterans of the British Army, having thrown in their lot with the Brits, against the Nazis, during WWII.)

There’s something so pleasing to me about the fact that the mighty Israeli army more or less owes its existence to a tiny little man with flyaway hair and a strong Eastern European accent. But it’s true: it was sixty-year-old Ben-Gurion, who stood five foot three on a good day, who shaped the core of what would soon become the IDF, one of the world’s most formidable armies. Pretty cool.

By 1947, the Haganah had started producing some of its own weapons – though it still lacked big-ticket capabilities like tanks and planes. It streamlined its branches and expanded its brigades. And – most importantly – it prepared a shift in strategy that would grow more pronounced as Arab attacks grew more severe. This was no guerilla force. No auxiliary unit embedded within another nation’s army. This was, finally, the first proper Jewish army in thousands of years. And it was ready for a fight.

As previous episodes have made clear, the Israel of 1947 and 1948 wasn’t exactly the economic, military, technological powerhouse it is today. So when I say they were ready for a fight, I don’t mean they were 100% confident in their weaponry, or their abilities, or their power. But the Jews had a number of things that their opponents lacked. And ultimately, it was those things – many of them intangible – that made the difference.

I mean, think about the state of world Jewry in 1947. We’re two years out from the Holocaust. A third of world Jewry is simply gone. If there’s a better motivator to defend yourself than a genocide that happened under the world’s watch, I don’t want to imagine it. The Holocaust proved to the Jews that they couldn’t rely on anyone but themselves. Which meant that nearly all the Jews in Palestine – even the hardliners in the Irgun and Lehi – were united behind one cause. It was fight or die. And in the wake of the Holocaust, “die” was just not an option.

Palestinian Arab society, on the other hand, had no such social cohesion. Muslim turned on Christian. Rival clans bickered and sniped. Many Arabs – particularly those who lived in heavily Jewish areas – simply got up and left. Those who could afford it decamped for less fractious shores, like Cyprus or Lebanon. Others simply relocated to Arab-majority areas within Palestine, like Gaza or the West Bank. And those who needed to stay put, whether because they couldn’t afford to move or because their livelihoods were linked to their land? Well, as one source reported it: “The fellah (peasant) is afraid of the Jewish terrorists… the town dweller admits that his strength is insufficient to fight the Jewish force and hopes for salvation from outside…” But there would be no salvation from either within or without. Palestinian society’s lack of social cohesion extended to their military. Simply put, there were too many groups running around. Small armed guerilla bands. The Arab Liberation Army. The Arab Higher Committee. All either unwilling or incapable of coordinating with one another. The wider Arab world was no better. True, other Arab countries roared and blustered and even sent troops – some of them experienced veterans. But they contributed little in the way of money or usable weapons. (In the words of historian Benny Morris, Saudi Arabia’s weapons shipments were, and I quote, “particularly decrepit.” Shade.)

Meanwhile, the Haganah, though scrappy, was increasingly well-funded in the later stages of the war, thanks to the largesse of global Jewry. Between March and June of 1948, Golda Meir raised upwards of one hundred million dollars for Jewish defense – money that ultimately helped the Haganah turn the tide in their favor. But we’ll get there.

The Haganah’s military prowess – not to mention the occasional brutality of the other paramilitaries – was well established. And so some Arab communities, keenly aware that war was at their doorstep, signed peace agreements that guaranteed they’d be left alone. They were serious about these agreements, even turning away Arab fighters seeking refuge or supplies. Others, like the Druze (who deserve their own episode, by the way), declared their loyalty to the future Jewish state, even forming their own unit within the IDF in the summer of 1948.

And I want us to pause here for a second, because this is important. As we said, today, historians describe this period of Israeli history as a “civil war.” In Hebrew, milhemet achim – a war of brothers. And there’s something so sad and so ironic about that designation. Because the Arabs and the Jews of Palestine could have been brothers. Before 1948, yes, there were clashes, but Arabs and Jews mingled, often regardless of their politics. Not enemies. Not combatants. It makes me sad to think about what could have been.

But at the same time, maybe I’m being nostalgic for something that never existed. As former mayor New York Ed Koch famously said, “It never was the way it was.” Because this was the birth of a state. And there is no birth that isn’t bloody, painful, and traumatic. No doubt the extremists on all sides exacerbated an already tense situation. All the way back in 1944, the hardline Zionist paramilitary group Lehi had threatened the British: “This is how you British will walk the streets of Zion from now on: armed to the teeth… and fear in your eyes… because the Jewish youth have become dynamite.”

Now, as the British prepared to leave Palestine, that dynamite began exploding in Arab towns. A New York Times article from December 1947 reads: “Three bombing incidents, attributed to the Jewish underground Irgun Zvai Leumi, killed today sixteen Arabs and wounded sixty-seven, of whom three are expected to die. These attacks confirm the recent impression that Irgun has rejected the Jewish Agency’s policy of strict legality and is carrying the fight to the Arabs.” Between November 29, 1947 and May 14, 1948, Lehi and the Irgun killed or wounded hundreds of Arabs, most of them unarmed civilians going about their business. In strict defiance of Haganah and Jewish Agency policy, these militias bombed marketplaces and blew up theaters, killing merchants and traders, women and children. Sometimes, their missions killed fellow Jews.

Every bomb was meant to intimidate Arab villagers to leave. To remind them this land is our land, not yours. And – as you’ll hear later in the episode – often, that strategy worked. Arabs fled in fear, carrying little with them but bloodcurdling stories of brutality.

Meanwhile, from the other side, Arab militias brought the war to Jewish communities. And though they were disorganized, poorly equipped, and often corrupt, these forces had one thing going for them. They had control of the roads.

If you’ve ever been to Jerusalem, you probably remember the journey there. Roads cut into the hillside, winding higher and higher. Ears popping slightly with the altitude. Random trucks on the side of the road. The sparse and timeless beauty of low trees and rocky cliffs and scrubby grass. It doesn’t matter how many times I make that trip. It always makes me catch my breath.

But the Haganah men driving poorly-armored trucks towards Jerusalem in 1947 and 1948 didn’t have time to reflect on the scenery. They were too busy scanning the road for an ambush. See, you might not think of supply runs as being particularly dangerous. You’d be wrong.

Because the Yishuv – and the Haganah – may have enjoyed social cohesion, and conviction, and money, and – soon – weapons. But many of its communities were geographically isolated, boxed in on all sides by Arab villages. And without heavy weaponry – like tanks – the convoys that supplied these isolated communities were at serious risk of attack.

Now, “convoy” might sound like a fancy military word. But in this case, we’re talking about a couple of cars or trucks jerry-rigged with some steel plating, full of food and medical supplies. And it doesn’t matter how good a shot the men or women inside may have been. They were outnumbered, and alone. The roads were surrounded by Arab villages. And they simply didn’t have the manpower – or firepower – to hold off an attack by armed gangs. Travel into Jerusalem became a game of Russian roulette.

OK, maybe you’re asking. Why not just forget about supplying these isolated communities and focus on a more defensible position? Well, because there were 100,000 Jews living in Jerusalem. And without supplies, they’d starve. And so the roads became a battlefield. Of the 136 supply trucks sent to Jerusalem in March of 1948, only forty one made it. Forty one. Out of a hundred and thirty six. To add fuel to the fire, every attack on a Jewish convoy touched off a revenge attack courtesy of Etzel and Lechi. Innocent people – Jews and Arabs alike – were dying. Arab states were howling. The entire region seemed poised on the brink of a bloodbath – a bloodbath with potentially global consequences.

And that’s why on March 17, 1948, the US approached the UN Security Council to suggest the Partition Plan be revoked and an alternate solution found – one that would be less, shall we say, violent.

Yeah, lemme say that again, because it’s crazy. Israel and the US both like to emphasize their “special relationship.” Pundits have written endless think-pieces about the “Israel lobby” – some accurate, some tipping over into antisemitic conspiracy. But few articles say much about the two states’ rocky beginnings. Because though the United States voted in favor of UN Resolution 181, the eruption of civil war in the region really freaked them out for reasons we’ll explain in episode 3.

Understandably, Yishuv leadership was livid. The Jewish Agency called the decision “shocking… we are at an utter loss to understand the reason.” But the Jews of Palestine – centrists and hardliners alike – had no intention of kowtowing to international pressure. The US’ new position was a big impetus for what happened next. Because David Ben-Gurion was not going to let his new state die before it ever had a chance to live. He would prove to everyone – the Arab states, the Americans, the whole damn world – that Jews were not merely victims. They would show teeth if they had to.

So he and the Yishuv leadership came up with a plan. They called it Tochnit Daled, or Plan D. (You might be wondering what happened to Plans A through C. In typical Jewish fashion, the Yishuv leadership debated their next move for a while. Plans A through C were merely the previous, never-implemented drafts of the final plan.)

We like to give different perspectives on Unpacking Israeli history. Depending on who you ask, Plan D was either a totally neutral, even positive, plan for defending the Jewish state; an ugly but necessary evil; or an unjust, unjustified policy of ethnic cleansing.

We like to give different perspectives on Unpacking Israeli history. Depending on who you ask, Plan D was either a totally neutral, even positive, plan for defending the Jewish state; an ugly but necessary evil; or an unjust, unjustified policy of ethnic cleansing.

I mean, just listen to these two very different descriptions from Israeli and Palestinian textbooks. According to Israeli textbooks: “In April 1948, the Yishuv leadership went on the offensive with Plan Dalet. The goals included: gaining control of the roads (capturing Arab villages in strategic locations overlooking roadways), gaining control of Arab neighborhoods in the mixed cities, and the conquest and evacuation of villages representing a threat to Jewish population. Via Plan Dalet, the Yishuv leaders intended to take control of the territory allocated to the Jewish state under the partition plan.” Sounds pretty neutral, even justified: simply taking control of what was promised.

But Palestinian textbooks tell a different story. “Plan D called for waging a wide-scale attack in order to seize Palestinian lands and keep them after the withdrawal of the British forces from Palestine. In this regard, Yigael Yadin, commander of the Palmach, declared: “Were it not for the entry of the Arab armies, there would not have been a way to stop the expansion of the Haganah forces, which would have been able to reach to the western natural borders of Israel, as most of the enemy forces were paralyzed at that time.” Which sounds a lot less neutral, doesn’t it? This textbook paints the Haganah as violent and expansionist, and it makes the invading Arab armies sound noble, stepping in to defend the Palestinians rather than attacking unprovoked. It’s a valuable reminder that the two sides see the war through completely different lenses.

Officially, Plan D’s only goal was the defense of the Jewish state along its 1947 borders, as described in the UN Partition Plan. But in practice, the plan did require the evacuation or destruction of Arab villages that dotted the way to Jerusalem. Ben-Gurion was done losing his people. It was time to take back the roads. Which is how the Haganah, whose policy had so long been “restraint” and “defense,” came to adopt a policy of either conquering or destroying strategically placed Arab villages that might pose a danger to the Jewish convoys making their way toward Jerusalem.

By April 1, 1948, the Haganah was ready to put Plan D into action. Golda Meir had returned from the first of two fundraising trips to the US with fifty million dollars – enough to buy a huge shipment of desperately-needed weapons from Czechoslovakia. (That’s over six hundred million in today’s money.) (And by the way, her second trip later that summer would bring in a further $50 million.) The weapons arrived in secret by air and by sea, one shipment hiding under a heap of onions and potatoes. Some Haganah fighters could barely contain themselves, kissing the rifles in relief. Finally: the top brass could stop borrowing weapons from local units or even random Jewish settlements, which were, understandably, not particularly enthusiastic about giving up their guns.

So the Haganah had the arms. The will. The plan. Now, it was time to turn the tables.

Plan D’s first official battle was called Operation Nahshon. And, side note, this is another one of those things that gives me chills. Because the operation was named after the Biblical figure Nahshon the son of Aminadav – who, according to the Rabbis, was the first person to walk into the Sea of Reeds during the Exodus from Egypt. Before the seas even split, Nahshon had enough faith in God that he waded into the sea until the water reached his neck. Only then did God part the waters. Israel’s founding fathers were largely secular. But they treated the Hebrew Bible as history, poetry, inspiration. Because what were they doing, if not conducting their own exodus, ushering in the Jewish people’s liberation?

Now, of course I wish that Jewish liberation didn’t involve bloodshed. But in April of 1948, the Jewish people felt they had no choice. The way they saw it – They could go on the offensive, securing their borders before the inevitable Arab invasion. Or they could keep playing nice and dying on the roads.

They chose the offensive.

Operation Nahshon had two directives. The first was to safely send a convoy from Kibbutz Hulda in central Israel to Jerusalem. The second was to ensure that the road from Hulda to Jerusalem would remain clear for future convoys. And to do that, the Haganah had to accomplish their second directive: conquering villages. They started with al-Qastal – a small but strategically important village west of Jerusalem that overlooked the road. (Nerd alert: the town was named for the Crusader castle that had been built there – a reminder both of European conquest and of the Muslim might that drove the Crusaders from the Holy Land. No doubt the name held great resonance for the Arabs defending it.)

But they didn’t stop with al-Qastal. They blew up the HQ of one of the militias operating in the area, killing dozens of fighters and prompting the Arabs of nearby villages to flee. And then, for good measure, they conquered two additional villages, securing the western portion of the road to Jerusalem. Kibbutz Hulda’s convoy reached Jerusalem without incident but with great fanfare from the city’s Jews, who cheered from the sidewalk as the sixty-car convoy chugged its way through the streets.

This mission, at least, had been victorious. But… that wasn’t true of Tochnit Daled’s other missions. See, the Haganah had conquered al-Qastal relatively easily. But they hadn’t given much thought to holding it. So when Abd al-Qadir al-Husseini launched the attack to take back al-Qastal, the Haganah scrambled to defend their position. And though they managed to kill Husseini, effectively crippling the Army of the Jihad, they lost many, many fighters to the wrath of Husseini’s men. And so Tochnit Daled took on an additional dimension. The Jewish paramilitaries had to be prepared to hold their positions. Otherwise, their victories were fruitless and short-lived.

Which brings us to a tragic chapter in this story. You see, once they realized their mistake, the Haganah had asked one of the other Jewish paramilitaries, Etzel, for help holding al-Qastal. But Etzel chose instead to conquer a different Arab village near Jerusalem. Fine, the Haganah said. Just make sure you hold the village once you take it. But I don’t think Etzel interpreted that command exactly how the Haganah intended. Because the village they chose to conquer… was called Deir Yassin.

We did an episode on Deir Yassin way back in season one. The link is in the show notes. Perhaps they chose Deir Yassin because it was very close to the Jerusalem neighborhood of Givat Shaul. And true, the residents of Deir Yassin had attacked Jews in the riots of 1929. But that was decades in the past, and by 1947, the Arab village had signed a nonaggression pact with its Jewish neighbor, even turning away Arab forces who showed up asking for shelter or support.

Well… mostly turning them away. Because in April of 1948, there were reports that the village was sheltering Iraqi and Syrian irregulars, who had begun firing on their Jewish neighbors. So despite the nonaggression pact, Etzel decided it was time to conquer the village and ensure the Jews of Jerusalem were safe.

And I want to be crystal clear about something. I keep using the terms “conquer” and “hold.” Conquer the villages. Hold the positions. But these are pretty ambiguous terms. Because conquer can include a lot of things. It can mean killing all the inhabitants of a village. It can mean letting civilians go but razing the village to the ground. It can mean turning the village into a military base, ensuring that its inhabitants cannot come back. I’m not going to shy away from the fact that Etzel discussed – and decided against – killing all the village’s inhabitants. But, I do want you to know that Etzel high command gave explicit orders not to harm the women, children, and prisoners of war.

The command was ignored.

We’ve already recorded an episode that recounts the gory details, and I strongly recommend you listen to it. Etzel and Lehi killed more than one hundred people – combatants and civilians alike – that day. The death toll was soon inflated to 250+. And along with the casualty rate, stories of Jewish atrocities – some no doubt true, some almost certainly exaggerated – began to circulate through the Arab countryside. A man ordered to throw his child into an oven, then thrown in himself when he refused. A boy tied to a tree and set on fire. Mutilation. Rape. Looting. Yair Tsaban, a former Member of Knesset and Palmach fighter, testified years later that “I don’t remember encountering the corpse of a fighting man. Not at all. I remember mostly women and old men.”

Why am I telling you these gruesome facts? Am I trying to demonize Etzel and Lehi? Trying to make Israel look bad?

No. I’m not. I’m trying to be honest. To show both sides. But I’m also trying to explain what happened next. Because you have to understand: Deir Yassin, as a village, had limited strategic value. But as a story? As a rumor of Jewish brutality? As a propaganda tool for all sides? It may have been the most important battle of the war. Its legacy has reverberated for 75 years and counting.

As reports of Zionist brutality spread throughout the Arab world, again, some fact, some fiction, Arab villages began emptying out. No one wanted their village to be the next Deir Yassin. Etzel’s leader, Menachem Begin, later commented that “the legend of Deir Yassin was worth half a dozen battalions to the forces of Israel. Panic overwhelmed the Arabs.” Even his rivals agreed. David Ben-Gurion. The British. Israel’s left-wing. All pointed to Deir Yassin as a “decisive factor” in the mass Arab exodus from Palestine.

But this is the Middle East, where the concept of an eye for an eye was invented. The Egyptians and Jordanians had been on the fence about whether to send in troops to fight the Jews once the British were out. But reports of the brutality at Deir Yassin, as well as Palestinian military setbacks, crystallized their resolve. The Jews had to be stopped.

The massacre had other, more immediate consequences. Four days after Deir Yassin, hundreds of Arabs ambushed a ten-vehicle convoy filled with doctors, nurses, students, professors, and wounded Etzel fighters on the road to Hadassah Hospital in Jerusalem. Six of the vehicles were able to turn around and flee to safety. The other four were not. The shooting went on for hours. But the convoy’s defenders exhausted their bullets. The Haganah’s rescue efforts were repelled. The Arab militias got closer and closer. They set the vehicles on fire, burning 78 victims alive.

I’m not telling you this to talk about the nature of good, or evil, or demonstrate who was good and who was bad. I’m telling you this because I want you to understand the more existential issue of war: namely, that war is hell. All of it. That the six-month period between partition and independence indelibly shaped the competing and enduring narratives – and traumas – of Israelis and Palestinians alike. And that the state of Israel was born in blood – some of it sacrificed on the battlefield, some of it stolen in a brutal cycle of revenge. Whatever your opinion on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, it’s important that you know this: both sides went through hell.

Ben-Gurion knew that more was coming. That these constant attacks were nothing in the face of a full-scale Arab invasion. And despite the partial success of Nahshon and its follow-up operations, Israel’s survival was nowhere near guaranteed.

We know what happens next. But Ben-Gurion didn’t. And that’s where this chapter ends. With excitement and uncertainty and anxiety and pain. With terror and grief and anticipation. With the knowledge that the fate of the Jewish people was poised on a precipice. And that whatever happened next would change the world forever.

Now, I want to let you know that the next chapter of this story is going to be tough. We’re going to delve into some of the pain and terror and grief of early 1948. But it’s a story that every single person needs to know. Because like so many of Israel’s stories, it’s become an important part of the Zionist narrative and the Zionist ethos. A narrative forged by the Jewish people, fighting for control of their destiny at last.