We’re curious…

“Arab society [in Israel] has completely lost its sense of security,” Thabet Abu Rass, an Arab citizen, told Haaretz earlier this month. “The amount of crime we’re witnessing in all Arab towns, especially in the Triangle area where I live, is truly scary.”

And on Sunday, Prime Minister Naftali Bennett underscored the severity of the issue: “We are losing the country,” he said.

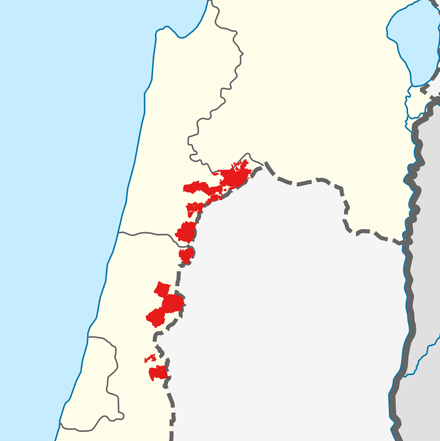

The Triangle refers to a largely Arab region in central Israel. It’s adjacent to the Green Line, within the most eastern boundaries of the Central District and Haifa District.

Violent crime in Israel’s Arab communities has surged in recent months: more than 100 Arab citizens of Israel have been killed, by Arabs, since the beginning of 2021. This is on track to make 2021 the deadliest year for the community in recent memory. The vast majority of the deaths involved guns.

Making matters worse, Haaretz reported that “the vast majority of killers are never brought to justice. Only 23% of the killings in the Arab Israeli community this year have been solved.”

The government seems committed to addressing the problem. Earlier this month, the government vowed to advance an unprecedented NIS 35 billion ($10.3 billion) in funding for the Arab community over the next five years.

The plan includes initiatives to fight crime, increase access to healthcare and improve infrastructure, and is more than triple the amount of the $3.8 billion Israel announced it was investing in the community in 2016 (which was then unprecedented).

Separately, the government announced that the Shin Bet (Israel’s internal security service) and IDF would be involved in efforts to fight crime in the Arab community, especially in combating the proliferation of illegal weapons.

This prompted a debate among Israelis about whether the Shin Bet — which is typically involved with counterterrorism activities in the West Bank and Gaza Strip — should be handling crime in these areas.

With the recent surge in violence in Arab towns, we wanted to unpack this issue and how we got here. First, who are Arab citizens of Israel? What do they think of the idea of the Shin Bet fighting crime in their neighborhoods? Is the government’s plan enough to reverse the trend of violence in Arab communities?

We spoke with Mohammad Darawshe of the Center for Shared Society at Givat Haviva, an organization promoting Jewish-Arab relations, to get his perspective on these questions. Darawshe was skeptical that the government’s plan would make a big difference, but he expressed hope in the future of the relationship between Israel’s Jews and Arabs.

How we got here: Who are Arab citizens of Israel?

First of all, what should the Arab community in Israel be called: Israeli Arabs, Arab citizens of Israel, or Palestinian citizens of Israel? And why does this even matter?

Kali Robinson of the Council of Foreign Relations explained that “the Israeli government and Israeli and global media tend to refer to the community as “Israeli Arabs.” Within the community itself, some “identify themselves as ‘Palestinian citizens of Israel’ or just as Palestinian to indicate their rejection of Israeli identity. Others prefer to be referred to as Arab citizens of Israel.”

So, who is this community? Arab citizens represent approximately 20% of Israel’s population. Most Arab citizens of Israel are Sunni Muslim, while a minority are Christian. In contrast to Palestinian residents living in the West Bank (which is governed by the Palestinian Authority), the Gaza Strip (governed by Hamas) and East Jerusalem, Arab citizens of Israel are Israeli citizens and have the same rights as Jewish Israelis under Israeli law.

However, many Arab citizens of Israel feel they are treated as second-class citizens, pointing to studies showing persistent socioeconomic gaps between Arab and Jewish Israelis.

The major difference between Israel’s Arab and Jewish populations is that unlike Israeli Jews, Arab citizens of Israel are not required to serve in the army. Some Arab citizens of Israel, especially from the Druze community, still choose to serve the army. In fact, 85% of Druze men serve in the IDF, primarily in combat units; this is actually higher than the percentage of Israeli Jews who serve (at a rate of 73%).

Studies show that there are indeed disparities between the two communities. According to a report by the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics, in 2018, the median monthly income for Arab citizens of Israel was 61% that of Jewish Israelis. Additionally, Israel’s National Insurance Institute (the equivalent of the U.S. Social Security Administration) published a report this past January showing that 35.8% of Arab citizens of Israel live in poverty, compared to 17.7% of the Jewish population and 23% of Israelis overall.

There are some signs that the situation is improving for Israel’s Arab community. First, in 2016, approximately 50% of Arab citizens of Israel were living in poverty, a significant decline in recent years.

Additionally, although Arab and Jewish doctors and nurses have long worked side by side in Israel’s hospitals, their cooperation was particularly visible in recent months, as medical teams of Arabs and Jews worked together to fight Covid-19.

On the political front, Mansour Abbas, head of the Islamist Ra’am party, made history this past June when he became the first leader of an independent Arab party to join a coalition government. One of the promises that Abbas secured from his coalition partners was billions of dollars in investment to fight violence and organized crime, and improve infrastructure, in Arab communities; now, the government is following through.

Despite these positive developments, there is also evidence that the situation for Arab citizens of Israel — and the relationship between the two communities — is getting worse. The record-setting number of murders in Arab cities and villages is a deeply worrying trend.

Additionally, this past May, during the war between Hamas and Israel, violence broke out in mixed Arab-Jewish cities. In the central city of Lod, Arab rioters burned synagogues and Jewish-owned stores, and attacked Jews on the streets of Israel, while Jewish extremists chanted “death to Arabs.” Leading up to this, threats of evictions in the East Jerusalem neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah escalated tensions between the two communities.

When we asked Mohammad Darawshe of the Center for Shared Society at Givat Haviva, an organization promoting Jewish-Arab relations, about current relations between the two communities, he said that overall, the relationship is healthier than it was last year, 10 years ago and 20 years ago.

“I think we have accumulated enough strength in the collective civic identity, and a great deal of interdependency in the medical industry, high-tech industry, and universities,” Darawshe said, adding that the percentage of Arab students in Israeli universities jumped from 3% in 2000 to almost 19% today.

“These are amazing accomplishments that testify to the fact that Jews and Arabs on the ground are actually learning to live together, they are succeeding in living with each other… We have a middle class that is beginning to develop. In the overall assessment, I think we are on the right track. I think we are accumulating more and more success stories between the two communities.”

Diversity of perspectives

When asked about his reaction to the government’s plan to invest billions of dollars in funding to Arab communities, Darawshe said that while he welcomed the proposal, money alone is not the solution.

He noted that despite the government’s previous, five-year investment in the Arab community in 2016, crime in Arab neighborhoods actually increased in that time. “We need an actual plan of solving the problems,” including solutions for education, recreation and employment for Arab youth.

Darawshe said that 40% of Arab youth ages 18-25 are in the streets, neither working nor studying. That 40%, he said, are responsible for 90% of the violence in the towns.

“You need to be able to absorb those people, either in extracurricular activities, or professional or academic training, to provide them something that creates some kind of connection between them and their community,” he said. “It’s not just about bringing in more police…but provide social, economic, employment solutions so that people can see a horizon in normal behavior.”

What about the issue of the Shin Bet? Both Bennett and Israeli Justice Minister Gideon Sa’ar defended the involvement of the Shin Bet in the fight against crime. Bennett explained that the measure is intended “to protect Arab citizens from the blight of crime, illegal weapons and murder.”

Similarly, Sa’ar said, “This is a hard situation and we need all of the state authorities” to address it, adding that the Shin Bet has valuable capabilities that could help combat the approximately 500,000 illegal weapons circulating in Israel’s Arab communities.

However, former Israeli attorney general Yehuda Weinstein disagreed with the idea that the Shin Bet was the appropriate agency to deal with the problem. “They are for a surprise solution to an extreme situation,” like capturing the prisoners who escaped from Gilboa jail, Weinstein said. “Their tools are for combating terrorism. I don’t think we are in a place yet where we need to use the Shin Bet.”

Meanwhile, Daniel Gordis reported that most Israelis “are very worried” about the situation. “The reports of murder in the Arab community every few days has become numbing and heartbreaking,” Gordis wrote. He added that the violence is also impacting Jewish communities: “Israeli Jews living in Jewish towns in the Negev report hearing shooting on a regular basis,” and some are afraid to leave their homes at night.

“As for what to do, no one has any great ideas,” Gordis continued. “Even explanations of the problem are contradictory. Some people explain that the crime is due in large measure to poverty and lack of opportunity…Others, though, believe that much of the crime stems from the growing middle class in Arab communities, with young people trying to angle in on the money.”

He concluded that “anyone who cares about the future of Israel must hope” that the situation improves. Justice Minister Sa’ar agreed, telling The Jerusalem Post that “the phenomenon of organized crime [in the Arab sector] endangers Israel more than external threats,” including Hamas and Hezbollah.

The bottom line

The question of how to integrate the Arab community into the Jewish state is not new: this is a challenge Israel has grappled with since the founding of the state. Even before Israel was established, Zionist thinkers and leaders were imagining how a future state would solve for this challenge.

Israel is mostly concerned with foreign policy and its relationships with neighboring Arab states, and on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict more locally, and it’s understandable that the Jewish state would be focused on these external threats. But the issue of violence in Arab towns — and the relationship between Israel’s Arab and Jewish populations — is no less important; in many ways, it’s much more important. The Israeli government seems poised to confront this challenge head on. For those who want to understand Israeli society and for all those who love Israel, this is an issue that should be on our radar.

Originally Published Oct 19, 2021 12:03AM EDT