What do Jerry Seinfeld, Helen Mirren, Sacha Baron Cohen, Sigourney Weaver, Bernie Sanders, Noam Chomsky, and Boris Johnson all have in common? Answer: They all volunteered on a kibbutz. So, what is a kibbutz and why did all these celebrities go there?

What is a kibbutz in Israel?

The word “kibbutz” comes from the Hebrew word for “group,” Kvutza. A “kibbutz” is like a cross between summer camp and boot camp for grownups. The kibbutz began as a communal farm, where everyone shared everything.

“Kibbutzniks” — as kibbutz members were called — shared the burdens of working the land, and the responsibilities of running and protecting the community. They shared profits (if they had any). And perhaps most important: they shared values that bound them together in a common purpose.

Kibbutzniks did everything together. They dressed alike, ate the same food together in dining halls, and lived in simple, similar-looking concrete blocks. Originally, even the children lived together — away from their parents — in communal children’s houses.

These kibbutzim were Socialist. There was no private property and everyone earned exactly the same amount. Unlike most socialist experiments, kibbutzim were also highly democratic. Kibbutzniks debated everything, from what crops they should plant to whether it was okay to buy a TV. These debates could go on for hours, deep into the night.

These kibbutzniks were also Zionists who were building the land of Israel. They were not just pie-in-the-sky idealists. They were pragmatic doers, getting the job done, working the land to build the state.

How the kibbutz movement grew

In 1909, 12 pioneers founded the first kibbutz, called “Degania.” Over the next 40 years, dozens of kibbutzim formed. They became romantic symbols of the Jewish people’s rebirth. A people raised to be scholars and merchants became farmers and fighters who made the desert bloom.

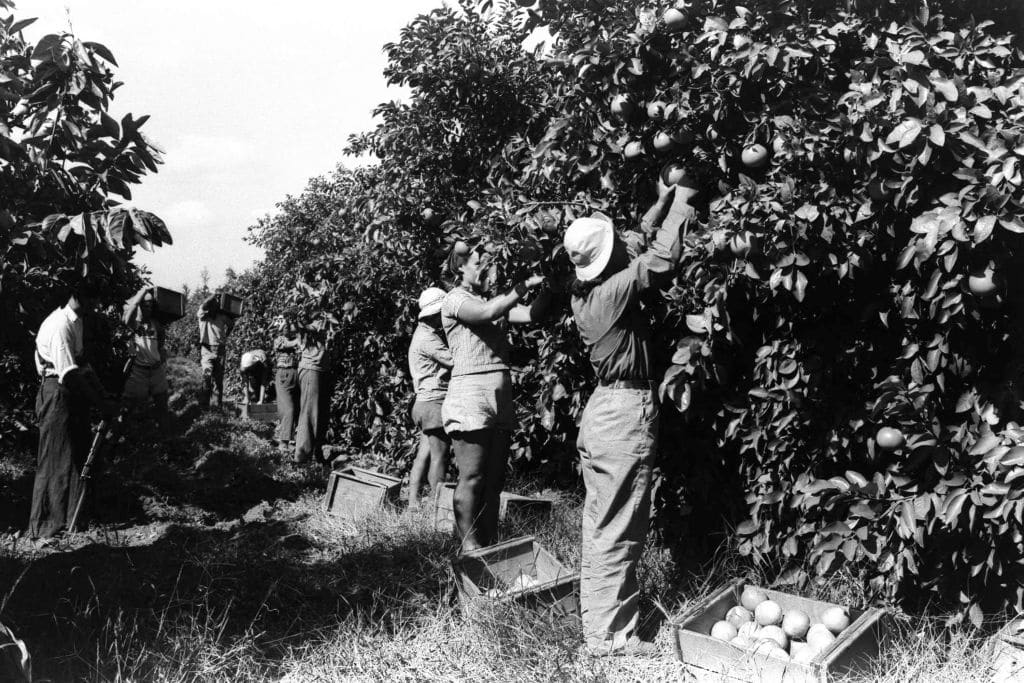

Reviving this long-neglected barren land was no picnic! Swamp by swamp, field by field, these communal farms helped turn the once-overwhelmingly brown country green. By 1948, only 4.5 percent of the new country of Israel lived on a kibbutz. But these new bronzed Jews, with shovels in their hands and rifles by their side, had an outsized impact.

They changed the Jews’ image and self-image as wanderers, peddlers, and victims, and flipped it on its head. While sweating day to day to transform the land, the kibbutzniks kept debating, brainstorming, and innovating, trying to make their communal experiment even more egalitarian.

Many kibbutzim were early laboratories for feminism. Women worked in the fields equally with men. For example, some kibbutz wives rejected the Hebrew word for “my husband” “ba’alee” (literally, “my master”), saying “eeshee” (“my man”) instead.

The challenges of kibbutz life

Living with such intense idealists wasn’t always so ideal. The environment of the kibbutz could be quite harsh. Workers deemed “lazy,” “bourgeois,” or “not socialist enough” could find themselves shunned, or, in extreme cases, even kicked off of the kibbutz!

Sometimes kibbutzim fractured over deep divides between more-moderate leftists and more-doctrinaire Marxists. In the 1950s, a few kibbutzim like Ein Harod, split when some of their members supported the Soviet Communist dictator Josef Stalin. To this day, two Kibbutzim, each named “Ein Harod” are located side by side, and are keeping the split very much alive.

As Israel grew, the kibbutz movement grew along with it. Especially during the 1960s and 1970s, kibbutzim made Israel popular, even trendy, with progressives worldwide. These Socialist Zionist communal farms showed off socialism at its most humane, happiest, and democratic.

The kibbutz is one of the most well-known expressions of Labor Zionism. Labor Zionists believed that through working the land, the Jewish people would not only rebuild themselves — they would also create an egalitarian, cooperative society. Read more about Labor Zionism and five other types of Zionism.

Celebrities who lived on a kibbutz

Over the years, more than 350,000 youngsters, especially from Europe and North America, have volunteered on a kibbutz. Some, like a 17-year-old Jerry Seinfeld, were Jews looking to explore their Jewish identity in an idyllic, rural setting. After exhausting days working the banana fields, Seinfeld and his buddies spent lots of time “hanging out” and telling jokes. Seinfeld himself has said: “My comedy career honestly, really, began at Kibbutz Sa’ar.”

Some of these volunteers were non-Jews. Helen Mirren, for instance, followed her Jewish boyfriend to Kibbutz Ha’on. Mirren recalls “being sent out with a big plastic bag to comb for grapes,” but also remembers being charmed by the country and its idealistic farmers in the months after Israel won the 1967 war.

Most volunteers were fascinated by this experiment in democratic socialism, including Bernie Sanders and Noam Chomsky, who told an interviewer: “I liked the kibbutz life and the kibbutz ideals.”

How the kibbutz has changed

Then the 1980s hit and things changed. In 1977, the Labor Party, Israel’s powerhouse political party led by Kibbutzniks, lost power for the first time. Inflation hit Israel hard, nearly bankrupting many kibbutzim. And this was precisely as farming became less profitable.

More and more kibbutz kids started opting out and moving to the city, lacking their parents’ ideology and zeal. As Israel became more consumerist, capitalist, and individualist, the Kibbutz started to look out of date.

Golda Meir once cut off a rival who started a sentence with the words, “I think.” “There is no ‘I’ here,” Golda said. “Only ‘we.’” But suddenly, “I” stopped being a dirty word in Israel. This new individualism posed all kinds of fresh challenges to the increasingly old-fashioned kibbutz.

Those who chose to remain realized they had to adapt. Most kibbutzim relented, allowing children to sleep in their parents’ houses. They hired more outside workers. They began to recognize individual members’ privacy and autonomy.

To profit, kibbutzim developed new business models, building over 350 factories and dozens of tourist guest houses. They hosted start-ups. They invented agricultural and irrigation techniques to feed and water Israel and the developing world. Today, kibbutzim are leading Israel’s entry into the medical marijuana business.

Kibbutzim in Israel today

Of 273 kibbutzim, 60 remain as communal as “Deganiah” was more than a century ago. The rest were privatized. While retaining a cooperative spirit, they did begin welcoming more outside income and allowing different workers to earn different amounts. More than 100 city communes, irbutzes (“ir” meaning city), have also emerged.

The kibbutz movement still punches way above its weight in Israel. Although constituting barely two percent of Israelis, kibbutzim generate 10 percent of Israel’s agricultural output and 9.2 percent of Israel’s industrial production.

Today’s kibbutzniks, 130,000 strong, also tell a story about Israel’s emergence as not just a start-up nation but a values nation. Israel has evolved in unimaginable ways since the first pioneering kibbutz experiment in 1909. But the kibbutz of yesterday still echoes in today’s Israel in Israelis’ strong sense of community, their culture of patriotism and sacrifice, as well as their simplicity, creativity, stubbornness and bluntness.

That’s why today, even as billions in new investments pour into Israeli high-tech and business ventures, millions of people still consider Israel one big kibbutz, a place where people still look out for one another, hope to change the world together, and are ready to argue about it anytime, anywhere, deep into the night.