In August, 2021, the Brooklyn neighborhood of Crown Heights came together for “One Crown Heights,” a day of music, entertainment, rides, children’s activities, and community conversation.

The atmosphere was reminiscent of the historic cooperation during the civil rights movement – when so many Jews stood together with Black Americans against racism.

The peace and joy on the streets was in stark contrast to the violence and mayhem that occurred on those same streets 30 years prior. In August, 1991, the extreme tensions between Jews and Blacks in Crown Heights exploded into 3 days of riots directed toward the Jewish community.

How did the relationship between these communities deteriorate so dramatically? And how did the sides rebound and rebuild the meaningful partnerships we are starting to see more of today?

Black and Jewish relations

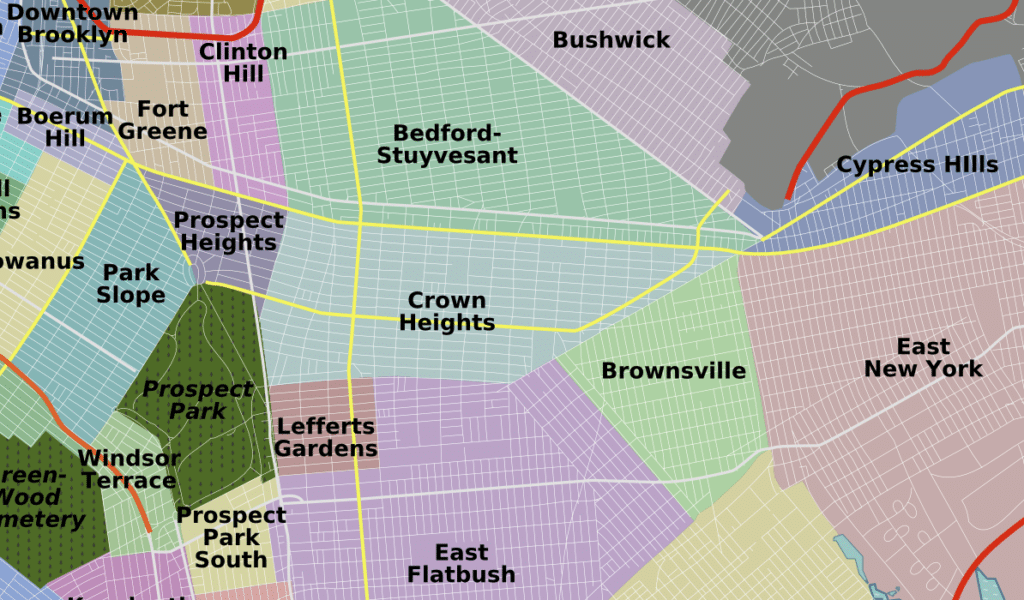

The civil rights movement brought Jewish and Black Americans together in the fight for racial equality and an end to discrimination. The movement was, perhaps, the height of the deep, trusting relationship between the two communities. The beginning of the disintegration of that relationship is best represented through the story of Brownsville, Brooklyn.

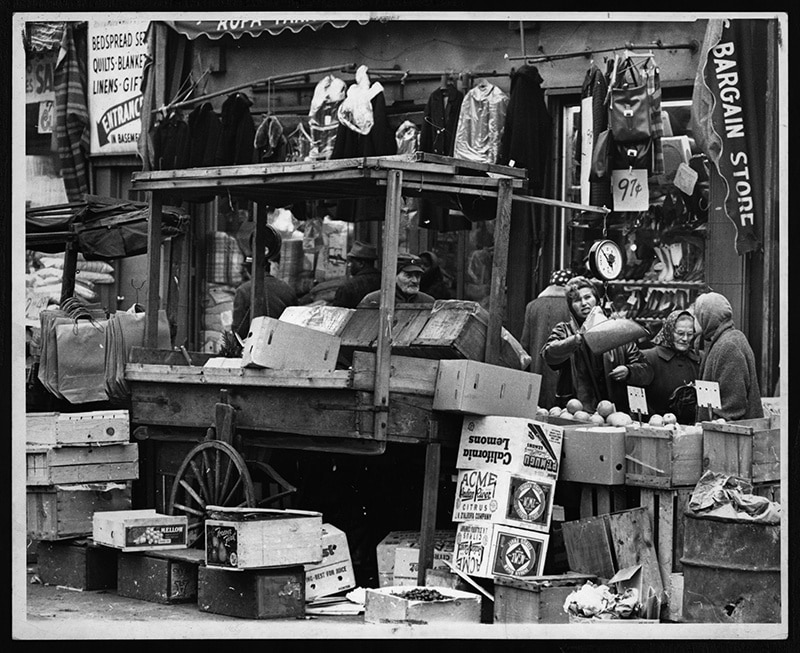

From the 1880s until the 1950s, Brownsville, Brooklyn, was mostly made up of Jews of European descent. In the first half of the 20th century, large numbers of Russian Jews came to America, fleeing persecution – and many of them moved to Brownsville. By the 1950s, the neighborhood had the highest density of Jews in America. “Little Jerusalem,” as it came to be known, was as diverse as the general American Jewish community; and included radical leftists, orthodox Jews, Jewish mobsters, and ordinary Jews raising their families and putting food on the table.

White flight

The adjacent Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood was home to the first large Black community in Brooklyn. At first, the two adjacent communities were well integrated with strong ties economically, educationally, and personally, despite some prejudices. The Brownsville Jewish community had a strong contingent of civil rights supporters, who opposed school segregation and other racial discrimination.

Just as the Black community started to expand, a shift in the American economy led to local factories closing down, hitting Black laborers hard. In the 1950s, the New York Housing Authority started building public housing projects in Brownsville. Due to rising crime rates and a need for greater social and economic mobility, the Jews of Brownsville quickly moved out and Black and Latino residents replaced them.

This relocation was occurring across the U.S. as Black neighborhoods expanded and White people headed to the suburbs, a phenomenon that became known as “white flight.” While nearly all the Jews left, many retained businesses and property in the newly-Black neighborhoods. Soon, interactions between Blacks and Jews, who had previously lived side-by-side, became increasingly defined by employer-employee and landlord-tenant relationships.

That change in power dynamics would increasingly sour the connection between the communities. As James Baldwin wrote (April 9, 1967 NY Times) “[T]he most ironical thing about Negro anti-Semitism is that the Negro is really condemning the Jew for having become an American white man.”

1968 teachers strike

In Brownsville, the predominantly Black schools still had some white teachers and administrators, many of whom were Jewish. In the late 1960s, Black community leaders, unhappy with their children’s education, fought for greater control over local schools. This culminated in the firing of 13 teachers and 6 administrators from Junior High School 271, almost all of whom were Jewish.

The firings violated the teachers union contract, which resulted in all New York City public school teachers going on strike. And it didn’t help that the public face of the strike, the head of the teacher’s union, was Jewish. The issue soon devolved into a struggle over class and race – and turned ugly; a few Black radio hosts even aired antisemitic content, in one on air interview the host read a poem that contained the lines: “Hey, Jewboy, with that yarmulke on your head / You pale-faced Jew boy – I wish you were dead.” Additionally, Jewish teachers claimed to have discovered antisemitic pamphlets among their students.

The strike lasted for 36 days and finally ended when a state education commission took control of the school district and reinstated the dismissed teachers.

National changes and tensions

The population movements that played a role in the Brownsville story were not unique. In Kansas City, for example, before and during the civil rights movement, Jews and Blacks lived and worked together on some of the most important legal cases tackling racial discrimination in the state. But by the 1970s, most Jews had left for the suburbs; as the communities changed and their priorities shifted over time, their common cause slowly evaporated. This kind of slow growing apart between communities was true from New York to Chicago to Los Angeles.

During this same period, affirmative action became another source of division as the government tried to address racial disparities in areas like employment, education, and housing.

While supporters of affirmative action felt it was necessary to rebalance the scales in America, many Jews were concerned. For over 100 years, Jews were subjected to antisemitic discrimination in the U.S. that limited their options in education, housing, and employment. But, the Civil Rights movement ended such institutional antisemitism, and American Jews were advancing socially, economically, and politically like never before. Some Jews felt affirmative action put Jewish advances at risk, and they felt the system was too close to the antisemitic quotas they had faced in the recent past. Color, they argued, shouldn’t matter: merit should. The Black community responded that although color shouldn’t matter, it does – and opposition to affirmative action is racist.

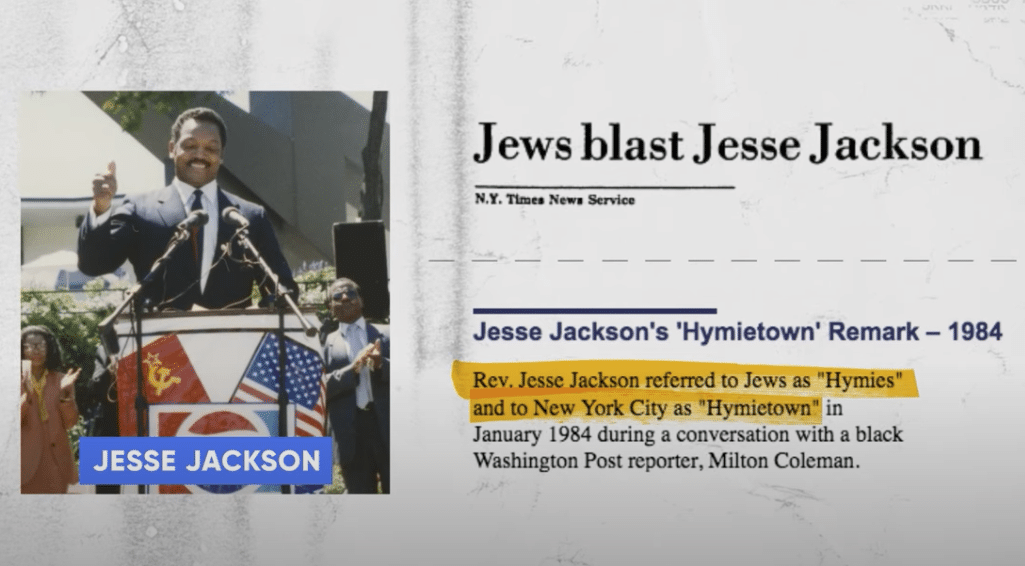

The end of the 1970s and the bulk of the 1980s saw more troubling divisions between the communities. Public expressions of antisemitism increased in the Black community. Presidential candidate Jesse Jackson even called Jews “hymies” during his 1984 campaign and Nation of Islam leader, Louis Farrakhan, called Judaism a “gutter religion.” But the tension didn’t prepare anyone for what went down in 1991.

Crown Heights riots

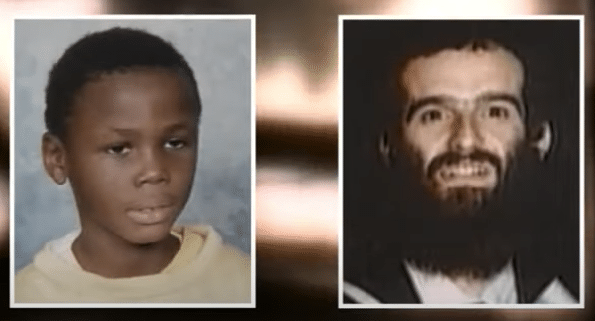

Tensions had been growing for years in Crown Heights, a neighborhood shared by Blacks and Jews. On August 19th, 1991 a driver in the Lubavitcher Rebbe’s motorcade lost control of his car and hit two Black children, killing one of them. At the same time, crowds of West Indian Brooklynites spilled onto the sidewalk from a reggae concert and began to gather around. There were murmurs that a local Jewish ambulance service, Hatzolah, showed up but only helped the Jewish driver. This was later disproven, but the rumor spread like wildfire.

Shouts of “Kill the Jew!” could be heard from the streets, and later that night, a 29-year-old Hasidic man, Yankel Rosenbaum, was stabbed to death.

Riots swept through Crown Heights for three days. Mobs of young Black men roamed the streets, targeting Jews and Jewish businesses, ambulances and police. The violence shocked the Jewish community. As historian Edward Shapiro writes, “It was the only riot in American history in which the violence was directed at Jews.”

In the aftermath of the Crown Heights riots, members of both communities realized that healing and cooperation were the best path forward. Against all odds, Black and Jewish leaders found commonality in the need to rebuild their shared space. In one memorable event, a Jewish teacher named David Lazerson and a Black teacher named Paul Chandler brought together a bunch of people from Crown Heights to host a public conversation so each side could feel heard. A mediation center for the communities was created in 1998. Over time, efforts like these continue to bear fruit.

More recently, in 2019, a bipartisan group of congressmembers announced the formation of the Congressional Caucus on Black Jewish relations “with the hopes of strengthening the trust and advancing our issues in a collective manner.” (Rep. Brenda Lawrence). In 2019, after two Black men murdered four people in a kosher market in Jersey City, Jews and Blacks overcame pain and anger to speak to one another, understand one another, and learn to confront difficult issues together.

Thirty years after the riots, the “One Crown Heights” event stands as a testament to the enduring efforts of Black and Jewish Americans to overcome their differences, see the humanity in each other, and build a better community together.

Originally Published Feb 16, 2022 12:02AM EST