Editor’s note: This article is part of a three-part series covering the untold Jewish histories of your favorite ice cream brands. Read Part 1 on Häagen-Dazs and Part 3 on Ben & Jerry’s.

Across the world, arguably the most well-known name in ice cream is Baskin-Robbins. However, its story of success — how the company evolved from a single shop into a worldwide empire, spearheaded by two Jewish founders — is not as widely-known as its creamy product.

Flavors like Jamoca Almond Fudge and Cherries Jubilee were born from the innovative thinking and creativity of Jewish founders Burt Baskin and Irv Robbins — at a time when Jewish entrepreneurs began to dominate the U.S. ice cream industry.

Whether you only frequent locally-owned ice cream shops or are a devoted Baskin-Robbins fan enjoying all 31 flavors each month, you’ll still be surprised to learn the fascinating Jewish history behind Baskin-Robbins, starting with a man named Irv Robbins.

Irv Robbins: From a family business to an ice cream empire

Born on December 6, 1917, in Canada, Irv Robbins grew up in Tacoma, Washington, where his father owned a downtown ice cream parlor. From the time he could lift a scooper, Robbins worked in his father’s store. He loved the joy he was able to give people by scooping out ice cream and “finished a day’s work happy.”

During college at the University of Washington, Robbins joined Zeta Beta Tau, the first Jewish fraternity, and studied political science, but knew he wanted to return to the ice cream business to continue spreading delight with his work.

After graduating, he further honed his skills as a lieutenant serving the U.S. Navy during World War II. Robbins began making ice cream for his fellow soldiers, innovating with new flavors and slightly-tweaked recipes.

After the war, the aspiring ice cream mogul tapped into his $6,000 bar mitzvah fund to open his first Snowbird Ice Cream shop in Glendale, California. He quickly earned acclaim for offering 21 different flavors — a surprisingly high number for a time when most ice cream parlors carried no more than five.

“There was really no such thing anyplace as a pure ice cream store,” Robbins told the Los Angeles Times in 1985. “I just had the crazy idea that somebody ought to open a store that sold . . . nothing but ice cream, and could do it in an outstanding way.”

In the 1940s, most ice cream parlors offered just vanilla, chocolate, strawberry, and coffee, often with an icy consistency and chemically flavored. But a shift was underway in the United States — creamy, dense ice cream was rising in popularity as businesses innovated to make richer versions.

On the East Coast, Jewish entrepreneur Reuben Mattus was crafting a recipe so thick and luxurious, it would redefine store-bought ice cream. He called it Häagen-Dazs.

Meanwhile, as Baskin-Robbins made its mark, it’s worth noting that currently, all Baskin-Robbins flavors are certified kosher, except for Rocky Road.

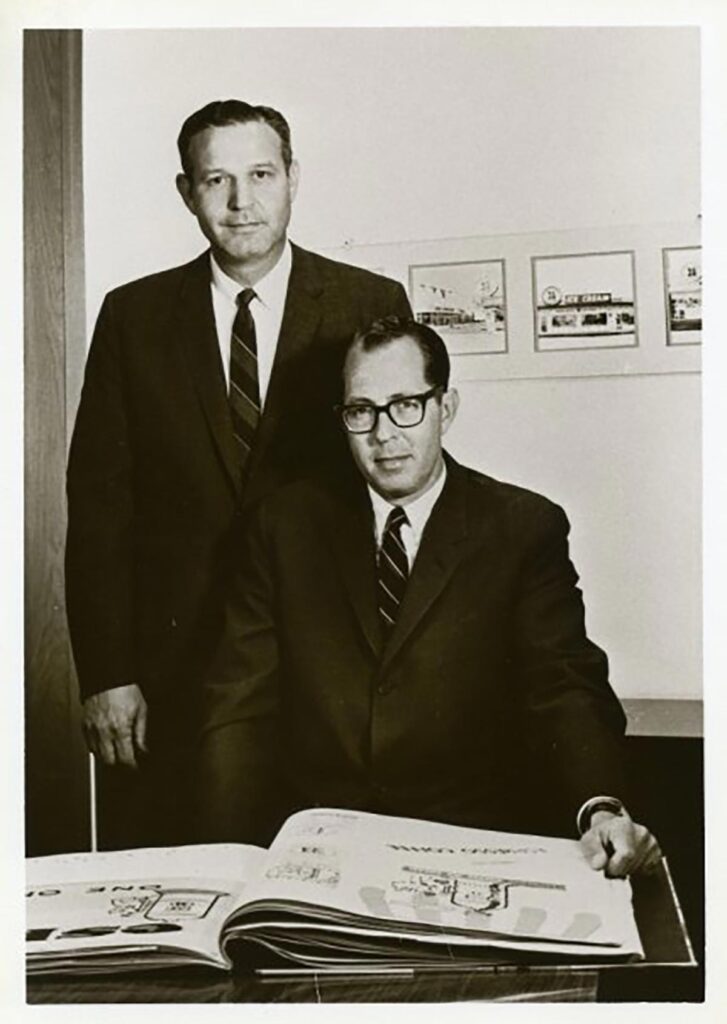

Baskin-Robbins: A family and ice cream business marriage

So, that’s the story of Robbins’ early life — now, let’s explore his partner’s journey. Born in Streator, Illinois, in 1913 to Russian-Jewish immigrant parents who ran a local clothing store, Burt Baskin attended the University of Illinois. Like Irv Robbins, he also joined Zeta Beta Tau. He met his wife Shirley Robbins — Irv Robbin’s sister — in 1941 and the two were married the next year in her hometown of Tacoma.

A member of B’nai B’rith Lodge 2625, a Jewish social advocacy group, Baskin served in the Navy during World War II. Upon returning home from the South Pacific in 1946, Baskin and Shirley moved to California, where Robbins was operating his Snowbird shop in Glendale.

Baskin began his career as the owner of a men’s clothing store, following in his family’s footsteps. However, his brother-in-law convinced him that selling ice cream was much more enjoyable than selling clothing, and Baskin founded Burton’s Ice Cream in Pasadena.

By 1948, the duo merged their eight ice cream parlors — five Snowbird locations and three Burton’s ice cream shops — to form one company enterprise. They retained their individual names on their stores, based on advice from Robbins’ father. The elder Robbins suggested they first build their businesses separately to understand their strengths and desires without conflict, and then consider merging.

Five years later, they united their shops under the iconic Baskin-Robbins banner, flipping a coin to determine whose name would come first. This merger resulted in the company’s now-legendary 31 flavors, one for each day of the month.

Baskin-Robbins became a quick hit for the variety of flavor options. Both founders focused on crafting innovative ice cream flavors, which resonated deeply with their customers.

Baskin-Robbins paved the way for food franchises across the country

As Baskin-Robbins continued to grow, opening more ice cream shops across Southern California, they noticed that they were able to pay less attention to each store they owned.

“[Soon after merging] we hit on selling our stores to our managers,” Robbins told the Los Angeles Times. “Without realizing it at the time, we were in the franchise business before the word ‘franchise’ was fashionable. We opened another store and another and another…”

Seizing an opportunity, Baskin and Robbins brokered deals with store managers, transferring ownership while stipulating the operational guidelines for each Baskin-Robbins store.

With these innovative agreements, they inadvertently set a milestone in restaurant history: Baskin-Robbins became the first food company to franchise. Their trailblazing approach later inspired their milkshake machine salesman, Ray Kroc, to replicate the model for his enterprise, McDonald’s.

Franchising allows businesses to license their name to entrepreneurs eager to establish their own branch. For company leaders, this model ensures each individual store is well taken care of since franchisees invest their personal funds.

For Baskin-Robbins, this approach let Baskin and Robbins focus on overarching brand development and flavor innovation, rather than the day-to-day operations of each ice cream parlor. Their strategic shift allowed the business to continue expanding without compromising quality or individual store attention.

Baskin-Robbins pioneered another industry first: providing franchisees with specific products made at a central facility.

The company also implemented certain policies across all the franchises, like offering customers unlimited free samples. Their iconic little pink spoon became a staple of Baskin-Robbins’ commitment to helping customers pick their favorite flavor.

Robbins put it this way: “Not everyone likes all our flavors, but each flavor is someone’s favorite.”

Baskin-Robbins’ swift innovation in flavor development

Baskin and Robbins were dedicated to having complete control over their ice cream production and flavor innovation. However, the lack of instant access to large quantities of dairy hampered their speed.

In 1949, to boost production, they purchased their first dairy farm, supplying milk to their 40 West Coast stores. This direct control accelerated their flavor creation process. Their ideas could be transformed into new flavors within days, leading to themed ice creams.

When the Dodgers, including Jewish baseball legend Sandy Koufax, moved to Los Angeles in 1958, Baskin-Robbins introduced “Baseball Nut” to honor the team.

In 1964, Robbins was asked by the New York Post how he’d honor the Beatles’ arrival in the U.S. to play on the Ed Sullivan Show. While Baskin-Robbins had no flavor in the works, Robbins replied, “Uh, Beatle Nut, of course.” Within five days, it was available in every store.

In 1969, the company celebrated America’s successful moon landing with “Lunar Cheesecake,” and the list went on. From their Burbank factory, the team devised hundreds of unique flavors, but only 12 would be promoted as the flavor of the month. This left flavors like “Ketchup,” “Lox and Bagels,” and “Grape Britain” to be scrapped on the tasting floor.

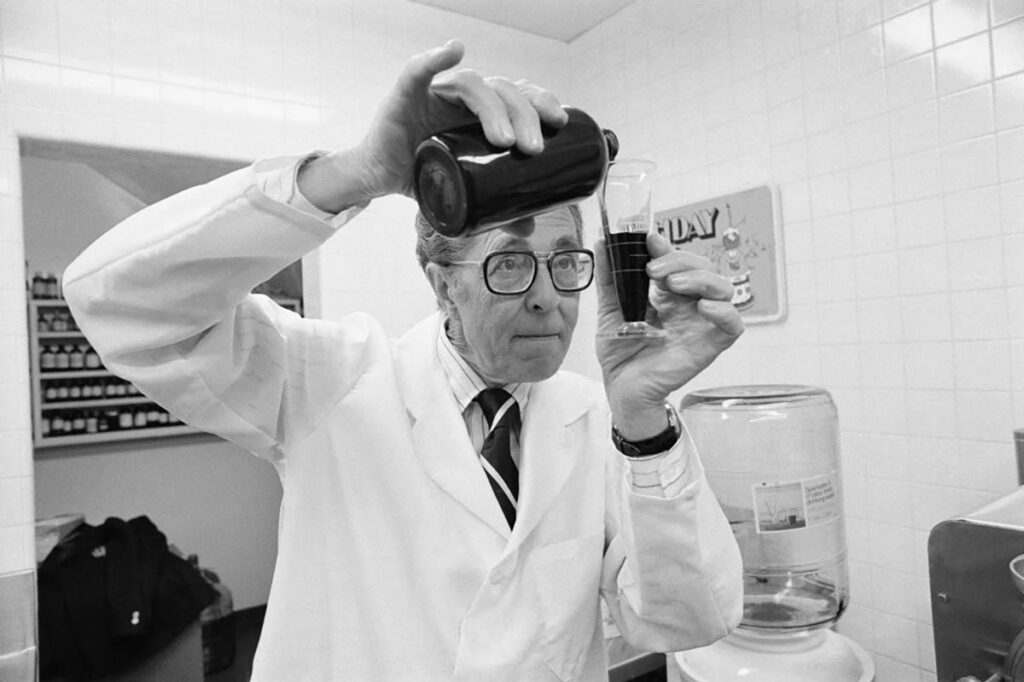

In an interview with the New York Times, Robbins — who prided himself on eating several scoops daily himself — proudly declared that the company’s rotating, exotic flavors allowed Americans to break out of their comfort zones.

“They’re not embarrassed to ask for some of these wild flavors,” he said. “I think we’ve had a little bit to do with making it more acceptable.”

Baskin-Robbins post-founders

In 1967, when Baskin Robbins had around 500 locations, it was sold to United Fruit Company (now Chiquita) for $12 million. Tragically, Baskin passed away from a heart attack six months later, at age 53.

Distraught and concerned about the health effects of mass-produced ice cream, Robbins’ son, John, distanced himself from the family business. He attributed his uncle’s untimely death to the very brand they had built. As John put it, “He was a very big man who ate a lot of ice cream.”

Meanwhile, Irv Robbins remained involved in the company he founded and lectured about entrepreneurship at UCLA and USC until he retired in 1978.

In his retirement, Robbins lived in a California mansion featuring an ice cream cone-shaped swimming pool and a personal ice cream bar with six flavors. He also enjoyed spending time on his boat, fittingly named “32nd Flavor.” While he may have withdrawn from business life, Robbins remained a local celebrity, and people often approached him with new flavor ideas.

Recalling one such encounter, Robbins told Investor’s Business Daily in 1999, “I’ve even had people stop me in my car, which has the license plate ’31 BR,’ on the freeway. I guess some people think it’s legal to stop on a California freeway if you’re doing it for ice cream.”

A new era: The union of Baskin-Robbins and Dunkin Donuts

As the decades went on, Baskin-Robbins sought new opportunities to continue its legacy. In 1994, marking a significant moment in its history, Baskin-Robbins was acquired by Dunkin’ Donuts. This iconic doughnut chain was founded by William Rosenberg, a fellow Jewish entrepreneur and son of German-Jewish immigrants.

With the combined strength of both brands, Baskin-Robbins expanded dramatically, eventually becoming the world’s largest chain of ice cream shops with over 8,000 locations. The brand not only integrated with Dunkin’ Donuts locations worldwide, but also further franchised on its own internationally.

Robbins passed away on May 5, 2008, at the age of 90. Until the end, his mornings began with a bowl of cereal topped with a scoop of banana ice cream.

The legacy of Baskin-Robbins

So, that’s the story of the two Jewish founders who shaped the Baskin-Robbins empire. Here are some takeaways from their story:

Irv Robbins and Burt Baskin not only changed the ice cream landscape with their staggering array of flavors. They also introduced the franchising business model, setting a precedent that countless others followed and kicking off the fast food revolution.

Their continuously innovative approach — from pioneering themed-flavors that reflected contemporary events to their transformative franchising model — laid the foundation for the brand’s enduring success.

For aspiring entrepreneurs, the story of Baskin-Robbins is a reminder that innovative practices — such as the simple act of offering unlimited free samples — not only showcase a product’s excellence but also create a genuine connection with customers.

Originally Published Aug 18, 2023 06:12PM EDT