Editor’s note: This article is the first of a three-part series covering the untold Jewish histories of your favorite ice cream brands. Read Part 2 on Baskin-Robbins and Part 3 on Ben & Jerry’s.

When you walk into your local grocery store, the freezer aisle may not be the first place you think to look for Jewish products.

But surprisingly, many of your favorite ice cream companies were actually founded by Jewish entrepreneurs. These iconic brands didn’t just magically appear, but were born from the tenacity, ambition, and creativity of Jewish creators, some even designing unique flavors inspired by Jewish holidays.

Even if your Ashkenazi genes have gifted you a sensitive stomach that recoils from dairy, or if you’re the type to prefer a silky swirl of soft serve, you’ll still be surprised to learn about the Jewish history of the most famous ice cream brands. Let’s start with the untold story of Häagen-Dazs.

Jews and the ice cream industry: A sweet and complex history

But first, let’s take a step back. What’s the connection between Jews and the ice cream industry?

Ice cream is often linked with Italian immigrants, who indeed opened a plethora of ice cream parlors across U.S. cities. In Europe, the frozen treat is typically connected with Italian vendors who peddled the treat from quaint carts and cafes. However, the role Jewish entrepreneurs played in shaping the industry is a lesser-told story.

Unfortunately, antisemitism adds a bitter note to this otherwise sweet tale.

In Britain, in the early 1900s, Italians ruled the ice cream trade. However, wild antisemitic conspiracy theories emerged. Jews were accused of “controlling” the influx of Italian ice cream vendors and corrupting British children with the sugary dessert.

During a 1903 immigration meeting in Britain, locals alleged that Italian ice cream vendors were encouraging children to consume ice cream on Sundays, promoting loitering around the cart. British newspapers portrayed these vendors as trying to “posion” the youth and undermine the British empire.

However, across the Atlantic, the story was very different. For the waves of Jewish immigrants setting foot on Ellis Island, ice cream was a sweet symbol of American culture. The officials who greeted them were convinced that serving new immigrants ice cream “was an efficient method for making our future citizens more at home in their new environment.”

Once settled in the U.S., some of these immigrants saw a chance to redefine the ice cream landscape. Moving beyond the traditional vanilla, chocolate, and strawberry, they experimented with diverse textures and flavors, turning a simple indulgence into an even more lavish experience.

As Mitch Berliner, a veteran food distributor with 35 years in the ice cream business, told Tablet Magazine, “Jews have always been entrepreneurs and think out of the box. Even about ice cream.”

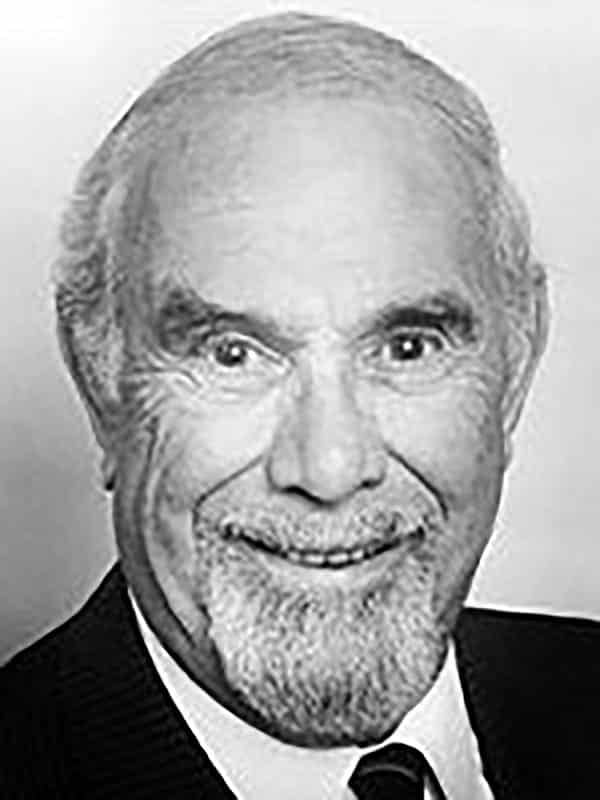

Creating an ice cream empire: The story of Jewish entrepreneur Reuben Mattus

One of those innovators was Reuben Mattus, a Jewish immigrant from Poland. After arriving in the U.S. at age 10 in the 1920s, Mattus worked for his uncle’s Italian ice business in Brooklyn, squeezing lemons with his widowed mother and selling the tart, icy treat from a horse-drawn cart.

Running an Italian ice business was difficult before the invention of refrigerators and freezers. Mattus recalled how his family would purchase ice from the Great Lakes region during winter and store it underground, insulated with sawdust, until it was time to sell in the summer.

Over the next decade, the Mattus family expanded their business to include ice cream sandwiches, chocolate-covered ice cream bars, and popsicles. However, these new products received lukewarm reception. To complicate matters, major ice cream suppliers instigated a price war against local vendors, putting extra pressure on the family to maintain sales.

Mattus, undeterred, believed he could change customers’ minds and keep his family in business — not by engaging in a price war, but by focusing on the quality of the ice cream itself.

“I realized I couldn’t keep up and maintain any kind of quality,” Mattus told People Magazine in 1981. “I thought maybe if I made the very best ice cream, people would be willing to pay for it.”

25 years in pursuit of the perfect recipe

Motivated by his desire to create a thicker, creamier ice cream, Mattus dedicated a quarter of a century to tireless experimentation. The result was an ice cream so rich and dense that it broke all of the family’s existing ice cream machines.

Mattus’ wife, Rose, also a Jewish immigrant from Poland, shared a unique anecdote in her autobiography, “The Emperor of Ice Cream.” She revealed that the couple discovered their final recipe somewhat accidentally, when the air injection pump in their ice cream machine broke, altering the ice cream’s texture.

Mattus’ magic formula increased the butterfat ratio for added creaminess and reduced air content for a denser scoop. He also swapped artificial flavoring and nonfat dry milk for all-natural ingredients sourced from across the globe.

@haagendazs_us That first taste happy dance. #thatsdazs #icecream #desserttok

♬ original sound – Häagen-Dazs – Häagen-Dazs

Mattus figured that this innovative, ultra-rich version of ice cream would exude an air of sophistication, particularly given that ice cream was already perceived as a luxurious treat.

An 1896 article in the Jewish women’s magazine, “American Jewess,” captured this: “Ice cream is generally regarded by families of limited means as a luxury only to be indulged in on special occasions, when company is expected or for birthdays and high holidays.”

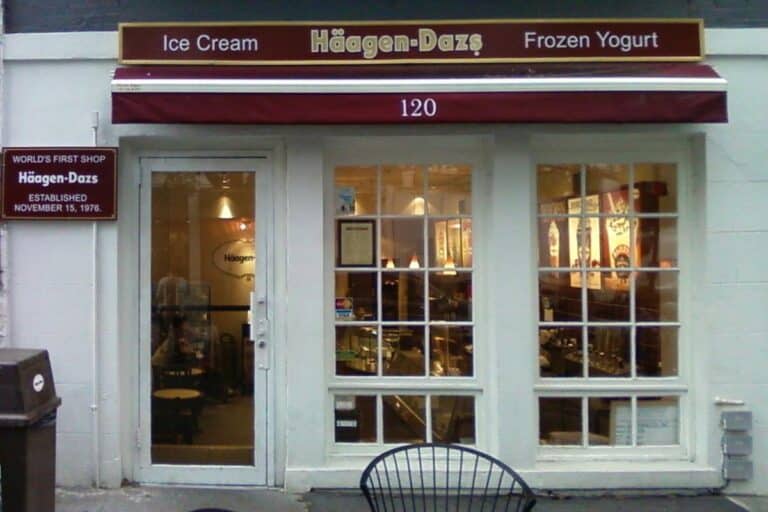

In a bid to appeal to a more affluent clientele, Mattus rebranded with a foreign-sounding name: Häagen-Dazs. A master marketer, he believed that wealthy Americans would be drawn to a brand with an exotic, European ring to it. He specifically chose a Danish-sounding name to honor Denmark’s notable actions in World War II.

“The only country which saved the Jews during World War II was Denmark, so I put together a totally fictitious Danish name and had it registered,” Mattus told Tablet, referring to Denmark’s 1943 rescue operation that ferried the majority of its Jewish population to safety in neutral Sweden.

DID YOU KNOW: Reuben & Rose Mattus, Polish #Jews, founded the renowned ice cream company @HaagenDazs_US. They chose a Danish(ish) name to pay tribute to Denmark’s efforts to save #Jews during the #Holocaust & were passionate about the fate of the Jewish people 🙏🇮🇱 @benshapiro pic.twitter.com/gZx78wBKj4

— Shahar Azani (@ShaharAzani) July 19, 2021

“Häagen-Dazs doesn’t mean anything,” Mattus admitted. “[But] it would attract attention, especially with the umlaut.” (The umlaut, or the two dots placed over the “a” in the brand name, are not even a feature of the Danish language.)

To further enhance the impression of the product’s Danish roots, Mattus printed maps of Denmark on the back of the cartons, implying a sense of imported sophistication.

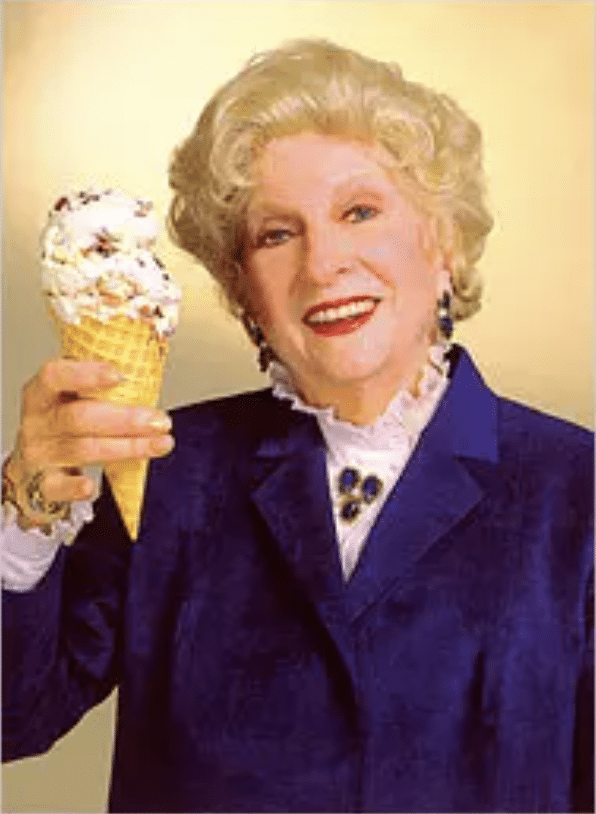

Rose Mattus: The business brain behind Häagen-Dazs

While Reuben Mattus focused on inventing new flavors, Rose played a pivotal role in shaping Häagen-Dazs’ business strategy. She spearheaded client expansion and meticulously built the brand’s image through ingenious marketing.

Rose started working as the bookkeeper for Mattus’ family ice cream business right after graduating from high school. Excited to work alongside her high school sweetheart, she quickly acquired an understanding of business and accounting. By the time Häagen-Dazs was launched, she was well-versed in the nuances of business operations.

“Rose was a true partner of her husband in operating the business, making decisions,” Roy Sloane, Häagen-Dazs’ advertising manager until 1987, said. “Reuben was a true dairy expert, a bug about quality. Rose basically ran the business, holding the company together and making it possible for a dreamer like Reuben to be successful.”

With this dynamic duo at the helm, Häagen-Dazs quickly gained popularity in New York City. Dressed in her finest attire, Rose hand-delivered samples to upscale grocers, who were quick to purchase pints for their affluent customers.

Häagen-Dazs sold at almost 50% more than its competitors in supermarkets, a premium price justified by Reuben’s belief that he had created “a special ice cream for people who wanted a special taste.”

The brand’s popularity grew primarily by word-of-mouth during these early years. Customers could not get enough of the high-quality ice cream and the air of luxury that the name Häagen-Dazs carried.

To further expand their clientele, Rose began offering free samples to local grocery stores and bodegas. She assured business owners that it would fly off the shelves despite the steep price.

By the early 1970s, Häagen-Dazs emerged as the only luxury ice cream brand in the U.S. with nationwide distribution. A name that initially meant nothing took on a new definition.

“We made a name and created a meaning for it. It means ‘the best,’” Mattus proudly declared in an interview with People Magazine.

Inclusive Marketing: Reaching overlooked communities

The Mattus family also embraced marketing toward groups other companies looked over.

Rose Mattus saw an opportunity in the burgeoning counterculture of the 1960s. Envisioning Häagen-Dazs being enjoyed by a younger crowd, she embarked on a cross-country tour, peddling Häagen-Dazs on college campuses from a Greyhound bus.

Despite its upscale reputation in Manhattan, Häagen-Dazs also became a go-to choice for satisfying “the munchies” among marijuana smokers in college towns.

“We found an alternate market, one steeped in the marijuana culture of the sixties,” Rose Mattus reflected years later in her memoir. “Our early clients were a motley assortment of oddballs with long hair, fringe tastes, and decidedly eccentric business styles.”

The strategy of inclusive marketing also extended to the Jewish community. From the outset, Reuben Mattus ensured that Häagen-Dazs was kosher-certified. “If I was to create exceptional ice cream, I wanted my people to enjoy it, so I made it kosher,” he said. This certification not only respected the dietary preferences of their community but also broadened the brand’s consumer base.

Following retirement, the Mattus family moves their focus from ice cream to Israel

In 1983, the Mattus family bid farewell to their ice cream empire, selling Häagen-Dazs to Pillsbury for $70 million. Their pioneering work in the ice cream industry inspired other entrepreneurs in the field, including Jerry Greenfield, the Jewish co-founder of Ben & Jerry’s.

“Rose and Reuben were pioneers and legends in the ice cream field,” Greenfield said.

Flush with funds and free time, the couple shifted their focus toward supporting Jewish, Israeli and Zionist causes.

“Though not observant in the religious sense, Reuben and I were always concerned about the welfare of others and passionately concerned about the fate of the Jewish people,” Rose Mattus wrote in her autobiography.

Rose served on the board of the Zionist Organization of America. Together with her husband, they donated millions to various cultural and educational initiatives in Israel, including funding the construction of a technology-focused high school in Herzliya named after them.

However, their philanthropic endeavors also attracted controversy. The couple faced criticism for their role in funding the construction of multiple settlements in the West Bank.

Moreover, the Mattus family’s support for ultra-nationalist rabbi and former MK Meir Kahane, the controversial founder of the radical Orthodox Kach Party and the Jewish Defense League (JDL), drew criticism. While some perceived the JDL’s mission to fight antisemitism as noble, others considered their methods violent and counter-productive.

Reuben Mattus died on Jan. 30, 1994 at the age of 82; Rose Mattus passed away on Nov. 28, 2006 at age 90.

The Häagen-Dazs success story: Embracing innovation and quality

Häagen-Dazs introduced luxury and diversity to an ice cream market saturated with low-quality products. The brand, feigning Danish origins, won over ice cream lovers nationwide with its high-quality offerings and playful branding.

“When I came out with Häagen-Dazs, the quality of ice cream had deteriorated to the point that it was just sweet and cold,” Mattus told the New York Times. “Ice cream had become cheaper and cheaper, so I just went the opposite way.”

The success of Häagen-Dazs hinged on a harmonious combination of Mattus’ tenacity in crafting an exceptional ice cream recipe and his wife’s keen ability to market it to the right clients. The brand is an example of what entrepreneurs can achieve when they understand their product and branding inside and out.

As low-income Jewish immigrants, Reuben and Rose Mattus used the skills they learned from their family business and their distinct expertise to magnify it into a worldwide brand. Their story is a testament to the transformative power of relentless innovation and a commitment to quality.

Originally Published Aug 9, 2023 05:13PM EDT