In the early 20th Century, American xenophobia and antisemitism, combined with the desire to fit in, pushed many Jewish immigrants to downplay their Judaism. They turned their backs on their old countries to embrace their new home, even when that new home wasn’t too happy to have them. But when their brothers and sisters in Europe faced a crisis of unimaginable horror, these American Jews were forced to reconsider their place in America.

While Jews began arriving in America in the 1600s, there were less than 200,000 American Jews until the end of the 19th Century, when over two million Jews from Russia arrived, fleeing pogroms. Unfortunately for these new immigrants, they arrived as part of a wave of over 20 million immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe that sparked a backlash among Anglo-Americans who wanted to keep out immigrants they considered racially or culturally inferior.

Congress passed the Johnson-Reed Act in 1924, limiting the annual quota of immigrants from each country to only 2% of the population from that country recorded on the US Census of 1890. Lawmakers purposely chose a census taken before the peak of the immigration wave to ensure the law would place strict quotas on Italians, Poles, Jews and other immigrants from outside of Western Europe. In doing so, Senators sought to massively decrease the immigration of what one of the law’s sponsors called, “men of alien speech and thoughts and habits.”

After the Johnson-Reed Act, the influx of Jews all but stopped and, as the Jews who were already in America had children, native-born Jewish Americans became a larger and larger portion of the population. These native-born Jews sought to rise beyond the hard labor and crowded tenements that characterized the lives of many of their parents. They excelled in school and pursued higher education to gain access to middle-class careers. By 1900, Jews made up 8.5% of college students despite representing only 2% of the US population and by 1935, 60% of native-born Jews in New York were working in clerical or related white-collar work, compared to only 10% of their immigrant parents.

Education offered an opportunity to join the middle class, but it also compounded the threat of assimilation. Public schools sought to “Americanize” Jewish children by promoting American values, celebrating holidays like Halloween and Christmas, and sometimes even encouraging them to look down on their parents for being “Greenhorns” who couldn’t speak proper English. As a result of these pressures, many young Jews rejected aspects of their Jewish identity and even changed their names to conceal their heritage.

Educated Jews with white collar jobs began to build a new Jewish middle class in the 1910s, 20s and 30s. These newly prosperous Jews often cared more about social and educational opportunities than religious responsibilities. To maintain the relevance of synagogues for these less observant Jews, many rabbis added events and classes that focused on cultural rather than religious concerns. For example, the bar mitzvah transformed from a meaningful but simple religious ceremony into an elaborate social affair with food and dancing.

While Jews embraced America, much of America didn’t reciprocate. Over 50% of Americans polled said that Jews were distinct from other Americans and shouldn’t try to mingle socially. As economically mobile Jews sought out middle class opportunities like universities, suburbs, and vacations, institutions restructured admission to keep them out. Suburbs relied on restrictive housing covenants and universities instated Jewish quotas, while many hotels and resorts simply banned Jews outright. Public figures like the famed pilot Charles Lindbergh and radio personality Father Charles Coughlin expressed sympathy for German fascism while the German American Bund drew over 20,000 supporters to a fascist rally in Madison Square Garden.

Barred from access to many aspects of middle-class America, Jews built parallel institutions that mimicked the organizations that rejected them, embracing American values despite American resistance. They established communities in neighborhoods like Grand Concourse in the Bronx and the Upper West Side in Manhattan that offered tree-lined streets and parks similar to the suburbs. They built community centers in cities and resorts in the Poconos and Catskills. But as the community was turning inwards and embracing the ideals in their new home, a new threat was rising back in Europe.

When the Nazis took over Germany in the 1930s, American Jewish communities struggled to reconcile their desire to help their Jewish brethren with their fear of rocking the boat. When a group of Jewish veterans boycotted German goods in 1935, the president of the American Jewish Committee called it “dangerous” because it would alienate the rest of America. Organizations such as the Joint Distribution Committee, formed by wealthy members of the Reform movement, and the Orthodox Vaad ha-Hatzala rescue committee did manage to fund rescue efforts that saved tens of thousands of Jews. Overall though, the response among American Jews was muted by a desire to fit in and avoid triggering further anti-semitism.

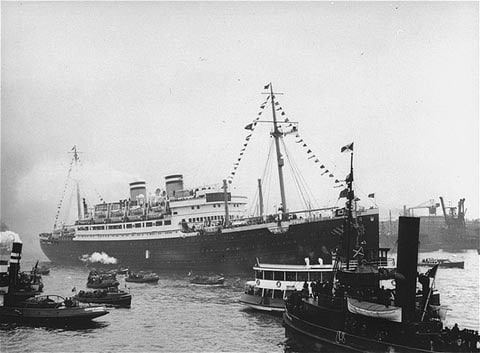

While it is impossible to know if a more forceful response from the Jewish would have affected policy, it is clear that the US Government proved tragically resistant to helping Jews escape the Holocaust. America accepted around 200,000 refugees between 1933 and 1945, most of them Jewish, but authorities rejected hundreds of thousands of desperate asylum seekers and boats of desperate refugees were turned back to die in Nazi gas chambers.

Once America joined World War II, the discovery of the full extent of the Nazi extermination machine galvanized Jewish and non-Jewish Americans to confront the horror of anti-semitic ideology. Open anti-semitism faded, institutions struck down quota systems, and the suburbs opened up to Jews.

Yet while America became more willing to integrate Jews, the devastation of the Holocaust pushed many American Jews to double down on their specifically Jewish identity. Between 1945 and 1965, the Jewish community built over a thousand synagogues, and the number of children attending Jewish schools more than doubled. While non-Jewish institutions became more accessible, the parallel organizations that Jews had set up grew even further, creating a vibrant uniquely Jewish identity in the postwar years.

Like so many immigrant groups in the past and the present, Jews fought for decades to be included in what it means to be American. They embraced the country’s ideals even when America rejected them. They struggled to straddle two identities with a complex, and at times antagonistic, history. This has resulted in a proud, complicated, diverse community that has found a way to build a hybrid identity, both Jewish and American.