The Holocaust didn’t start with death camps. It was a gradual process, a slow burn that eventually erupted into an overwhelming catastrophe. But by that point, it was too late. The fire was raging. The boxcars were full. Within 12 years, Europe’s diverse and thriving Jewish communities had turned to ash.

How did the Holocaust start? Post-World War I Germany

World War I left Germany in tatters. Millions of Germans were dead. And it was the victors who determined Germany’s fate after the war. Germany didn’t want to sign a treaty that demanded it reduce its military, give up territory, and pay other countries for the cost of the war — but they didn’t have much of a choice.

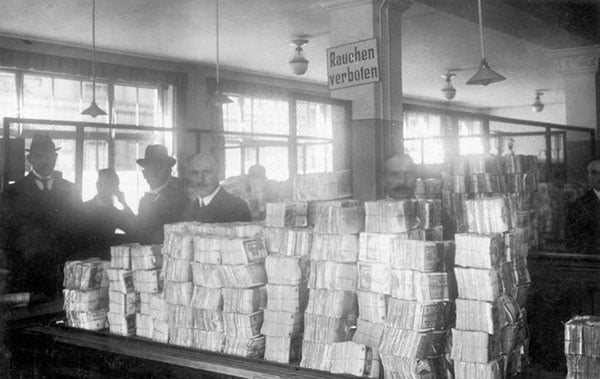

Ordinary Germans seethed with anger and humiliation. And their feelings of betrayal only intensified as their country buckled under the weight of reparations payments. By 1923, the German mark was more or less worthless. The government was printing billion-mark notes, and they weren’t enough to buy a cup of coffee.

People were desperate, demoralized and angry. How could their leaders have allowed this to happen?

The Nazis provided German society with a perfect scapegoat — the Jews.

Jews have lived in Germany for over 1500 years. Some of those years were good, but most were not. But by World War I, Jews were German citizens, many of whom served their country proudly during the war. Though some of Germany’s Jews were quite religious, a significant percentage were fully secular and integrated into German society. Still, they maintained their Jewish identity, a marker of their difference.

By 1923, the Nazis were ready to seize their moment, but the German government wasn’t ready to cede its power. The Nazis’ attempted coup failed miserably and Hitler was charged with treason and sentenced to five years in prison.

But Hitler didn’t exactly suffer in jail. In fact, he used this time to write a 720-page book called Mein Kampf outlining his life story and his vision for Germany. By the time he left prison, having served less than nine months of his five-year sentence, he was ready for a career in politics.

The coup had convinced him that violence wasn’t the answer. If he wanted real power, he’d have to get it legally. But the Nazi Party got less than 3% of the vote in the 1928 parliamentary elections.

The Great Depression and the rise of the Nazis

That should have been that and it would have been if not for the stock market crash of 1929.

The Great Depression erased whatever progress Germany had been able to scratch out in the years after World War I. As people grew impoverished and disillusioned once again, Nazi ideology started taking off. In the 1932 election, the Nazis managed to garner 37% of the vote. It wasn’t enough to make Hitler the president of Germany, but it was enough for the current president to start getting worried.

So, instead of ignoring the Nazis, President Paul von Hindenburg took his advisor’s very bad suggestion to heart. “Keep your enemies close,” they told him. And that’s how Hitler became the chancellor of Germany — effectively making him head of the German government.

But if President Hindenburg had hoped to control Hitler, he was in for a rude awakening. In his first month as chancellor, Hitler convinced the president to suspend individual rights and due process.

Overnight, the German government gave itself the power to round up political dissidents, censor newspapers, overthrow state governments, and outlaw political organizations it didn’t like. Ordinary Germans, whether Jewish or not, could no longer rely on freedom of speech or assembly. And they could no longer trust the media, which was now another arm of the state.

But Hitler wasn’t going to stop there. By March of 1933, he’d built a concentration camp to house his political opponents. And then he began the systematic process of stripping Jews of their rights.

The slow build-up to the Holocaust

First, he organized an anti-Jewish boycott. Then, he forbade Jews from holding civil service positions or practicing law. He was crafty, though. Some Jews were allowed to keep their civil service jobs — if they met certain strict conditions.

Then came the quotas. Soon, Jews could no longer make up more than 5% of any public school or university. Those who were allowed to stay were forced to endure the grotesque new Nazi curriculum.

All of this was legal, and protesting grew increasingly dangerous. Follow-up laws targeted the so-called “undesirables” of society — the mentally or physically disabled, non-violent or low-level offenders, and even alcoholics.

It was a test. Would German society protest a government measure to keep them “safe” by eliminating criminals? Did German society really object to the government keeping the gene pool strong by weeding out the sick?

There was only one check on Hitler’s power: German President Hindenburg. But he was 86, and dying of cancer. When he passed away in the summer of 1934, Hitler passed a law that made him both president and chancellor. The last check on his power was gone.

Germany’s new president-chancellor-dictator banned Jehovah’s Witnesses, made homosexuality a crime, and passed race laws that stripped Jews and other racial minorities of their citizenship and their protections under the law.

Herschel Grynszpan: Protesting against the Nazis

The Nazis needed everything needed to look legal, so they waited for a pretext. They found it in Herschel Grynszpan.

Grynszpan was only 17 when he entered the German embassy in Paris with a pistol. He asked to speak to a diplomat, any diplomat. He got a young Nazi named Ernst vom Rath. “You’re a filthy Kraut,” Grynzspan told vom Rath in perfect German. And then, he shot him five times.

Grynzspan didn’t resist arrest. A postcard in his pocket explained why he’d killed the Nazi. His parents, along with 12,000 other Polish Jews living in Germany, had just been deported without cause. Grynzspan was horrified and heartbroken.

He wrote to his mom and dad: “I could not do otherwise. May God forgive me, the heart bleeds when I hear of your tragedy and that of the 12,000 Jews. I must protest so that the whole world hears my protest, and that I will do. Forgive me.”

Kristallnacht: The night of the broken glass

The whole world heard his protest but it was soon drowned out by the sound of breaking glass. The Nazis seized their chance. They framed the whole affair as proof of a Jewish conspiracy against all Germans.

It was time to punish the architects of Germany’s misfortune. Nazi top brass instructed their three paramilitaries to raise hell in Jewish communities across Germany. Police and fire departments were told not to intervene.

They stood by as the SA, SS and Hitler Youth burned synagogues, vandalized Jewish cemeteries and destroyed Jewish property. They beat Jews to death in the street, and German police deported 30,000 Jewish men to Dachau and Buchenwald solely because they were Jewish.

German Jews scrambled to escape, but there was nowhere to go.

How did the world react to Kristallnacht?

The world condemned Kristallnacht and President Franklin Roosevelt even demanded the American ambassador to Germany return home. But no one stopped trading with the Nazis. Even Germany’s harshest critics were reluctant to take in the masses of Jewish refugees scrambling to get away.

The Nazis’ plan had worked. The police had fallen in line, just as instructed. The fire department had let the synagogues burn. Neighbors watched, but few, if any, protested.

The rest of the world could mouth platitudes about how awful this was, how uncivilized, how bad they felt. But no one was taking concrete action. No one sanctioned or protested the Nazis and no one took in the thousands upon thousands of refugees who needed somewhere to go.

Kristallnacht: The start of the Holocaust

Many historians view Kristallnacht as the start of the Holocaust because it just might have been the moment that the Nazis realized that they could get away with it. They took this as proof that they could do whatever they wanted to the Jews.

Things were moving quickly now. Within seven years of Kristallnacht, two-thirds of Europe’s Jews would be gone.

The reason we commemorate the Night of Broken Glass each year is because this was the moment that reality sank in. It’s a reminder to us to be vigilant and to intervene when we see something go so terribly wrong. It’s a reminder to make good on our promise of Never Again.