Schwab: Welcome to Jewish History Nerds, where we do exactly what it sounds like, nerd out on awesome stories in Jewish history.

Yael: I’m Yael Steiner, and my childhood dream was to stay in school forever.

Schwab: I’m Jonathan Schwab, and I am in school forever. Yael, I woke up this morning in the mood for a great nerdy Jewish history story, so I hope you have a good one for us today.

Yael: Of course you did. How else do you ever wake up in the morning? Well, I’m glad to tell you that today we’re gonna be talking about a woman who I have admired for a very long time, and who might be well known to some of our listeners and is quite well known in the state of Israel. We are going to be talking about some of the little known background of Hannah Szenes.

Schwab: Based on you saying that it was a woman you admired who was famous in Israel. I thought it was gonna be Golda Meir, but Hannah Szenes is an even better option.

Yael: You didn’t think it was gonna be Netta from Eurovision?

Schwab: Didn’t cross my mind, but that also would be a great choice for a topic.

Yael: Have you seen the Eurovision movie?

Schwab: The Will Ferrell one?

Yael: Yes. So good.

Schwab: I was like, is this is the movie about real Eurovision or just the one making fun of it? Yeah, that one is great. Love it.

Yael: Let’s put that aside. Hannah Szenes was a Hungarian-born Jewish poet, writer, Zionist, and paratrooper who paratrooped or parachuted, I don’t know if paratrooped is a word, into Yugoslavia in 1944, crossed over into Hungary and was executed after being tortured and refusing to give up radio transmission codes that she had memorized. That is a way fast-forward into this story.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: But just to give some of our listeners who may not be familiar with her, a sense of what she did and why she’s important and why she has become a hero on a national scale in Israel. But we’re gonna take it back to her childhood, what kind of person she was, what inspired her and what her legacy is. Is she someone you learned about in school?

Schwab: Yes. Forever etched into my mind is, I wanna say it’s either fourth or fifth grade. And our Hebrew teacher was telling us the story of Hannah Szenes and our Hebrew teacher was Israeli and did not have perfect English. She kept referring to Hannah Szenes as a parachute, and we kept trying to tell her, “I don’t know what you’re trying to say, but I don’t think she’s a parachute.”

Yael: (laughs) Maybe in the spirit of Hannah being a poet, your teacher anthropomorphized the parachute. And just combined, you know, “Hannah was one with her parachute.” But that might be going a little overboard. So, yes, Hannah Szenes is someone who is taught about in many Jewish day schools, in all Israeli schools, and in many Jewish homes around the world. Because of her unusual story and her unusual heroism for such a young woman. When she was executed in 1944, she was only 23 years old.

Schwab: Oh, wow.

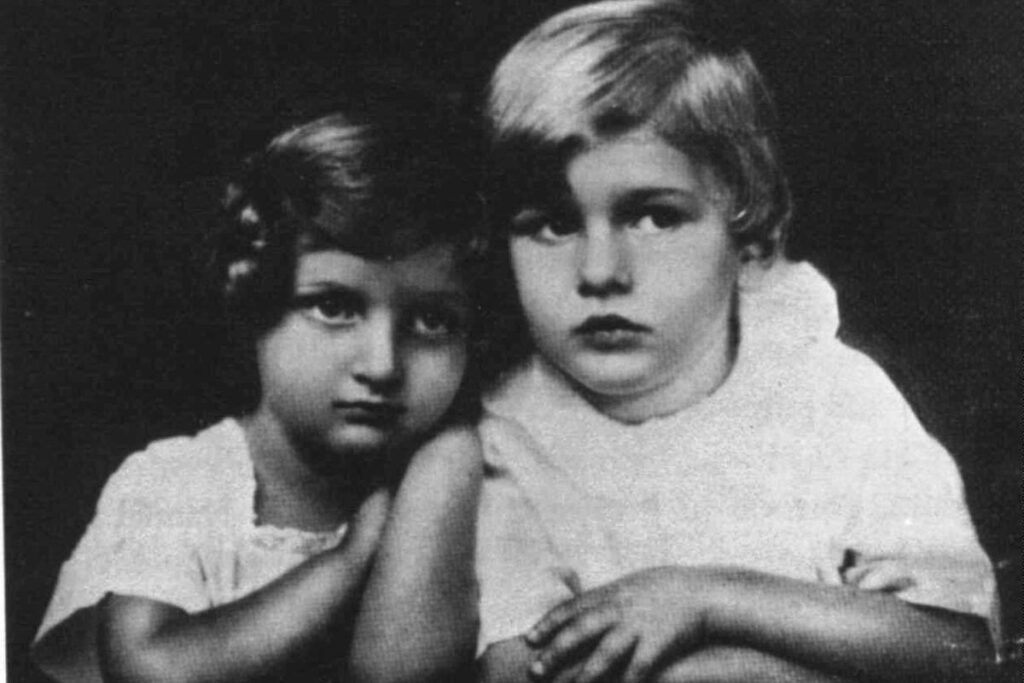

Yael: So I’ll take you back to the beginning of her life. Hannah Szenes was born in Budapest, Hungary in 1921. She was the daughter of Bela and Catherine Szenes. Bela Szenes was an extremely well known and popular Hungarian playwright whose works were admired widely in Budapest. She had one brother, George, he’s later known in Israel as Gyorga, is also known I think as Gyorgy, which is Hungarian for George.

Schwab: All these Hungarian names, very familiar to me because they are all my great-great-grandparents names. Like Bela, Gyorgy, we got ’em all in the family.

Yael: I’m also Hungarian, and I think that’s part of the reason that I have a soft spot for this story, but there are actually a few others as well. One is obviously, as a young girl, learning about Hannah Szenes when most of the heroes, both in American life and Jewish life that we learned about were men, was unusual. And so I think I took note of her especially. I also sang some of her poetry. Some of her poetry has been very famously put to music, but one of her songs, Halikha LeKeisarya, A Walk to Caesarea, is one of my favorites, an extremely, extremely powerful poem. I am not going to sing it for you, though. I have been singing it in its entirety, very operatically throughout my apartment for the past several days.

Schwab: Of course.

Yael: And when I was in college, I visited a 102-year-old woman who lived nearby through a fellowship with the Claims Conference that provides reparations or helps get reparations to Holocaust survivors. I visited this 102-year-old woman who was bed bound and basically blind, but what we did together was read the poetry of Hannah Szenes and talk about her.

Schwab: Wow, that sounds really powerful.

Yael: Mrs. Rubin. This was a long time ago, and she was 102 then, so she is no longer with us, but that was a very powerful experience for me. And I think one of the reasons we were able to bond over Hannah Szenes, though at that time we were 80 years apart, was that her story and her heroism transcends generations.

Schwab: So how does a poet become a paratrooper?

Yael: Great question. So she’s born to Bela and Catherine in Budapest. They are a proud Jewish family, though not traditionally observant, and she, Hannah attends a Catholic school. The way the Catholic school was set up is interesting. There’s one price for Catholics, Protestants pay double that price. And Jews pay triple that price. She was an extremely, extremely talented student. She really rose to the top at school. And in her seventh form, she was unanimously elected to hold the title of literary chair of the literary magazine. And that was a position that normally went to the girls in the eighth form. And not only was she not in the eighth form, but she was also a Jew. And the girls in the eighth form kind of revolted, and the title ended up being taken away from her and given to another girl. And that girl went to Hannah crying, apologizing, and just really telling her that she felt she wasn’t deserving and that Hannah was the much more deserving one.

She started keeping a diary at 13, and she was really a very eloquent, well-spoken and talented girl. The experience of having been stripped of that title on the literary magazine also really sparked something in Hannah with respect to her Judaism. She became more acutely aware of antisemitism, and she became an ardent Zionist.

Schwab: Hmm.

Yael: In 1939, when she was 18 years old, that ardent Zionism caused her to decide to go to Palestine. Unfortunately, that was also the time when World War II started.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: And people were no longer able to leave Hungary to go to Palestine. She goes to the Jewish Agency to speak to someone she was connected to there. And the gentleman at the Jewish Agency happened to be a fan of Hannah’s father’s plays, and he had one visa left to leave Hungary. And because he was a fan of Hannah’s father, he gave that visa to her, but she had to leave the very next day.

Schwab: Wow.

Yael: By that time, Hannah’s father had passed away. And her brother had previously gone to Paris. So she was leaving her mother alone in Budapest. Something her mother was obviously not happy about, but she did go the very next day and leave for Palestine. She goes to a women’s agricultural school in Nahalal. She does extremely well there. She, of course, speaks at the graduation ceremony for her classmates, to her classmates.

Schwab: This was not taken away and given to a Catholic student instead.

Yael: No, it was not. And she joins a Kibbutz called Sdot Yam, which is outside Caesarea.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: Caesarea, as we’ve spoken about in the past, was a city built by Herod, very much in the Roman style, very beautiful.

Schwab: Check out episode one of this season, if you don’t know what we’re talking about.

Yael: Yes. And one of her famous poems, which I mentioned earlier, “A Walk to Caesarea,” has been set to music and is basically now considered a hymn in the state of Israel. And it’s a very beautiful and very powerful.

Schwab: Which you’re not gonna sing.

Yael: (laughs) Do not tempt me. She continues to journal, write poetry, and she’s working on this Kibbutz, and she’s very successful at it. She’s successful at everything she does. She’s a real renaissance woman. And in fact, I watched some video testimony of her friends at the Kibbutz, and you could tell by the way that they spoke about her that they admired her tremendously and they loved her. And one of them said, “All we really wanted was for her to grow old with us.”

Schwab: Wow.

Yael: But Hannah wants to do more for the Jewish people. She gets to Palestine in 1939. So in the ensuing years, things have gotten substantially worse for European Jewry. And she hears about a British plan to gather volunteers to do some kind of work on behalf of the Allies in Europe. And she volunteers. Out of the 200 and something volunteers, 30 odd people are chosen. She’s one of them. And she’s one of only three women. And these 30 odd people are trained as, not parachutes, but paratroopers.

Schwab: (laughs): She was just one of these people who was so talented, like everything she touched she could do well, like, fantastically talented poet, and then also just physically gifted enough that was chosen for this.

Yael: You know, when people have passed, the things that they’re good at tend to rise to the top. But if you do research into her life, you really see that everything she touched was fantastic.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: The National Library of Israel has some wonderful artifacts of Hannah’s, her typewriter, her writings, her journals, her diploma from agricultural school. I read some letters that she wrote to the headmistress of this agricultural school about why she wants to be there. And you could just tell that there was this real fire in her.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: So in addition to being artsy and emotionally in touch, she was also obviously physically very capable as she trained to be a paratrooper. Something that most of the poets I know probably would not be able to do.

Schwab: Most of the athletic people I know are not always the best poets.

Yael: Fair enough. Sweeping generalizations there, but fair enough. And in March 1944, she parachutes into Yugoslavia with the plan of fighting with the partisans. Three days later, the Germans move into Hungary. Up until that point, Hungary had been an ally of the Germans, but the Germans had not been in Hungary. But when Hannah jumped into Yugoslavia, she was not under the impression that the Germans were in Hungary. And it appears to us now in hindsight, that she had a personal agenda in parachuting into Yugoslavia, that her plan all along was to cross into Hungary. Specifically to save her mother.

Schwab: Right. That’s what I was gonna ask.

Yael: So her mother is in Budapest. And her mother has no idea that Hannah has trained for this mission.

Schwab: And hasn’t seen her in five years. Right?

Yael: Correct. I do believe they wrote letters to one another. But her mother is under the impression that she is safely working on a Kibbutz outside of Caesarea, has no idea that she has undertaken this heroic enterprise. And because the Germans move into Hungary just a few days after their jump, the entry into Hungary by Hannah is delayed. And she ends up fighting in Yugoslavia with the partisans until June 1944. So she arrives March 1944, and she doesn’t cross into Hungary until June 6th, 1944, which some of you may recognize as D-Day.

Schwab: D-Day.

Yael: So auspicious timing. Also auspicious, or inauspicious timing from March to June, from the time that the Germans entered Hungary, there was a major, major deportation of Hungarian Jewry to Birkenau. Hundreds of thousands of Hungarian Jews were deported. In fact, by the time that Hannah entered Hungary in June, and we don’t know whether or not she was aware of this at all, the only Jews who remained in Hungary were the Jews in Budapest. Everyone outside of Budapest had been deported.

So, you know, she may have heard about the deportations and wanted to get to Hungary faster to see if her mother, she may have thought her mother had already been deported. We’re not 100% sure what information reached her, because she would have been getting information either from the British or from the partisans. So we’re not 100% sure what she knew, but it was a very inauspicious time for Hungarian Jewry during those few months that Hannah was in Yugoslavia. She crosses into Hungary on June 6th, and she is immediately captured within a few hours. Even though she is technically a British paratrooper and she is uniformed as a British paratrooper, when it is discovered that she is a Hungarian-

Schwab: And, Hungarian and a Jew, or just when it’s realized that she’s Hungarian?

Yael: To my knowledge, this had little to do with her being a Jew, and almost everything to do with her being a traitor to Hungary.

Schwab: Ah, okay.

Yael: They put her in a Hungarian prison as a traitor. The Germans don’t jail her, the Hungarians do.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: If she had been a run-of-the-mill British paratrooper, she probably would have gone to a prisoner of war camp. She is taken to this prison where she is heavily, heavily tortured. And through an unbelievable amount of resilience, she does not give up the radio transmission codes that she has memorized that are key to the British and probably their communication and strategy. And that is why they’re torturing her to get these codes or any other information, because as I mentioned, it had just been D-Day, and the war is about to take a tremendous turn against the Nazis and their collaborators at this time, the Hungarians. So they’re starting to get extremely, extremely worried.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: And so it’s just terrible, terrible timing to be captured as a Jewish and British soldier in Hungary at that time.

Schwab: I don’t know if there were any good times to be captured as a Jewish British soldier in Hungary.

Yael: Probably not. And she’s put in this prison in Hungary, they get nothing out of her.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: She won’t talk. And obviously they could kill her, but I think they are hopeful that under continued torture, she will give up what she knows.

Schwab: How do we know about this part of the story? Like obviously we have her diary and stuff previously, but like how do we know about what happened to her in prison?

Yael: That’s a great question. We actually have a lot of testimony of her fellow prisoners. But we also have the memoirs of Catherine Szenes. And why the memoirs of Catherine Szenes are relevant here is that when Hannah refused to give up any of this information, whoever’s running the show there decides they’re gonna bring in Catherine Szenes to the jail and jail her.

Schwab: Wow.

Yael: And hope that that is sufficient motivation for Hannah to give up something. They basically put her mother in a cell on the other side of the courtyard from her, where they could see each other-

Schwab: The person she came to Hungary to save.

Yael: Basically, yes.

Schwab: And hasn’t seen in five years.

Yael: And hasn’t seen in five years. And her mother gets to jail and has no idea that Hannah has returned to Europe.

Schwab: Oh, wow.

Yael: Which is another amazing thing about this story that I haven’t brought up before. But this is someone who had the immense good fortune to get out of Europe in 1939 as a Jewish woman and make her way to Palestine.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: Most of the refugees from Europe were trying to get to Palestine or the United States, and she volunteers to go back.

Schwab: Yeah. I know there’s more of her life to discuss, but it’s so easy to see how she is a national hero of Israel because it really represents this sort of like ethos of what Israel is, of it’s not just a place to run away to it, it stands for the safety of the Jewish people. Like there’s this Israeli Zionist obligation to make all Jews in the world safe.

Yael: Yes. And it’s interesting that you say that. One of the historians whose lectures I listened to in preparation for this podcast says that Hannah Szenes was the perfect hero for a nascent state of Israel because she embodied both the intellectual excellence that the Jews wanted to bring to their new state, but also specifically the physical excellence, the fighting, he actually used the word Maccabean to describe it. And that’s obviously something we’ve talked about in the past. He said, “The heroes of the new state of Israel were David who fought Goliath.”

Schwab: And obviously this is, this is like a stereotyping, it’s not actually true, but the image of a Holocaust victim who was not able to or did not, you know, like resist in any way. And counter to that is this like Israeli symbol of fighting wholeheartedly. Oh, and like with physical strength.

Yael: Exactly. I think why Hannah Szenes has been canonized almost in the state of Israel. Exactly. And skipping ahead, because I already told you that she’s ultimately executed. When her body is repatriated to the state of Israel in 1950, she is given the most extravagant of state funerals. Her body, I think, travels for three days through the state of Israel until she’s buried in Har Herzl.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: Which is extremely unusual for a Jewish funeral in general. They’re usually very simple, but she was such a national hero. And also the state was not particularly religious at that time. Certainly significantly less religious than it is now. But before we get to her burial, let’s talk about how, unfortunately, she gets to that point.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael Bringing her mother into the prison does not work. Her mother is ultimately released about two months before Hannah is executed.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: Her mother during those two months tries desperately to intervene on Hannah’s behalf with government officials, Jewish leaders, anyone that she thinks might be able to help. She’s unable to do so, and in November 1944, Hannah is executed by a firing squad in the courtyard of the prison.

Schwab: Like, by Hungarians as a traitor to Hungary?

Yael: Yes. And she refuses the blindfold that she has offered. She wants to face her executioners.

Schwab: How do you know that detail?

Yael: So I watched some video testimony of other prisoners in the jail in Budapest. And the way one man described it, he just described the way her body crumpled. And that word crumpled was so evocative to me.

Schwab: Yeah. That’s like really vivid.

Yael: We really do know a lot about her and a lot about what happened to her, because there are a lot of people who saw what happened to her in prison and survived, because it was a Hungarian prison, it wasn’t a concentration camp.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: There were a lot of other non-Jewish Hungarians there, so it wasn’t as though most of the people in this jail were then taken to a death camp and killed. There are a lot of people who were ultimately released from that prison and lived to tell the story.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Yeah. And it sounds like she’s not one of these characters who later is made into a hero, but during her life, people even recognize that, like, while she was in prison, people already saw like, “Wow, this is a heroic person.”

Yael: So I watched a lot of videos of people talking about the Hannah they knew. And in one video I saw a name that looked very familiar to me, it was the name of someone who went to my synagogue growing up.

Schwab: Oh, wow.

Yael: I didn’t know her well, but I definitely met her and liked her. She was a lovely, lovely woman. And she grew up in Hungary, and I found out for the first time while researching this podcast, she was in prison with Hannah Szenes.

Schwab: Wow.

Yael And, she and her parents had been trying to flee Hungary, and they were caught, and they were put in this prison. And the few minutes of interview that I saw with her, she talks about how clear it was that Hannah was a special person and how much she admired her, how she admired how she carried herself, even though she was beaten and bloody, and had her teeth kicked out, and the way that she spoke about how you face your oppressor. When they were leaving either the prison or another place where they were being held during the Shoah, it was suggested to her, this woman, that if she gives up a gold watch and a gold ring that her family had, that they might be saved. And she knows from her conversations with Hannah, that that is not true.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: And that she thinks to herself, she’s like, “What would Hannah do in this situation?” And she flushed the watch and the ring down the toilet. And said, “I’m not handing this over to someone who is going to kill me anyway.”

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: So that was eerie to me, that I knew this woman who was in jail with Hannah Szenes.

Schwab: There’s something sort of Jewish about that.

Yael: So like Jewish.

Schwab: Somehow we just like are connected to, you know, through not too many degrees of separation, like all the other Jews, you know, like Jewish heroes are not that far away from us.

Yael: It’s true. This particular woman also mentioned in her video that she visited Catherine Szenes in Israel many years later. Catherine and her son, visited her later on in the United States, and they maintained a correspondence. And she said that Catherine’s home, she lived in this small house and it was a shrine of Hannah, understandably so. Catherine worked very, very hard at making sure that Hannah’s story was told. She published Hannah’s diaries. She got Hannah’s poems published. And I wanna read a few-

Schwab: Yeah. Definitely, yeah.

Yael: … of Hannah’s poems. They’re short.

Schwab: I assume that she grew up not writing in Hebrew-

Yael: Hungarian.

Schwab: And then when she was in Israel, she wrote her poetry in Hebrew?

Yael: Yes.

Schwab: But you’re gonna read a translation of it in English?

Yael: I’m gonna read a translation. But it, it’s still very poignant.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: One of the poems she wrote, called “Stars,” is unbelievable in its prescience. Like, she had no way of knowing what her fate would be. And based on other things I’ve read about her, you know, she was extremely confident, maybe overconfident and arrogant in certain ways. So I can’t believe that she thought she would come to the end that she came to. But when you read this poem, you think she could have been writing it about herself in retrospect. It’s unreal.

“There are stars whose radiance is visible on earth, though they have long been extinct. There are people whose brilliance continues to light the world, even though they are no longer among the living. These lights are particularly bright when the night is dark, they light the way for humankind.”

“There are stars whose radiance is visible on earth, though they have long been extinct. There are people whose brilliance continues to light the world…they light the way for humankind.”

Schwab: Wow. Yeah. I love that.

Yael: Which is a poem that someone would write about Hannah Szenes.

Schwab: Yeah. And it’s so fitting this idea of just like the light that is created only reaches us, but the source is gone at that point.

Yael: Yeah. And aside from “The Walk to Caesarea,” which I mentioned before, which is a national hymn in Israel, there’s one other poem that is very famous of hers that basically every Israeli school child knows. And, an interview that I watched with an officer in the paratroopers, he mentioned that this poem is a guiding ethos of the tens of thousands of paratroopers that have come in her wake. It’s called “Ashrei HaGafrur,” Blessed is the Match. And it’s not a perfect translation, but it’s good enough.

“Blessed is the match consumed in kindling flame. Blessed is the flame that burns in the heart’s secret places. Blessed is the heart that knows for honor’s sake to stop its beating. Blessed is the match consumed in kindling flame.”

“Blessed is the match consumed in kindling flame. Blessed is the flame that burns in the heart’s secret places.”

It’s a little creepy in that she seems to know what’s gonna happen to her. But she really was a very talented writer all around.

Schwab: And it sounds like she, I mean, just from the poetry and from the stories you were saying that she believed in sacrifice for a greater cause, like that was, something that, that she, like believed was really valuable of there are people who need to give up things so that others can have something or so like, so a greater cause can live. Yeah.

Yael: She left her mother alone in Budapest to build up the state of Israel. She certainly had no way of knowing how the war would play out or what would transpire in the subsequent years, she left in ’39. So she had no clue what was coming for the Jewish people, but she felt very strongly about going to Palestine to build up her ancestral homeland.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: And then even though she is there safe and thriving, she’s beloved. She is doing so well on the Kibbutz. And while we know that the Jews in the in areas outside of Europe didn’t know everything that was going on with respect to the final solution, they certainly knew something and she volunteers to go back in, and to jump out of a plane! Like I won’t even go recreational skydiving. I’m overwhelmed by the story of Hannah Szenes.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: So I don’t even know that I could encapsulate in a few minutes here what she means to me personally or what she means to the Jewish people writ large. But I’m glad we are having this opportunity to talk about her because she is astounding. She is just astounding.

Schwab: We’ve talked about so many, like historical occurrences and people and heroes especially. And we often complicate those stories and say, here’s what’s, like more difficult about their story and parts we need to grapple with. And it feels like there isn’t that element here.

Yael: I will say, just so this doesn’t become sort of, hagiographic and just fawning.

Schwab: Mm. She also tweeted some stuff that just like in retrospect looks really bad.

Yael: (laughs) Yes. There’s a woman who made a film about Hannah, who said that she tried to make a film about Hannah immediately when she graduated from college-

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: … because she had read Hannah’s diaries when she was a kid and just was amazed by her. And unfortunately that film didn’t work out and she wasn’t able to make the film until many years later when she was already a mother and she had a totally different perspective on Hannah and she was actually much more interested in the perspective of Catherine, who wrote her own memoirs.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: But this particular woman, she says the more she learns about her, she realizes that, her crossing into Hungary at that time based on what was known was extremely irresponsible and the undertakings of an arrogant young girl, and that she was extraordinarily arrogant. Obviously, this is one person’s take, and also being arrogant is not, exclusionary to being a hero many of our heroes are. But that going into Hungary at that time was really irresponsible. And that probably also led to the death of at least one of the other paratroopers because two people, followed her, in one of whom was killed later on. Hannah was not responsible for his death. But it’s possible that had Hannah not had the personal agenda of trying to save her own mother, she would not have been as gung ho about entering Hungary at that time. So this woman took a little bit of the shine off.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. It matches the idea of like, When I think of Hannah Szenes, I don’t think here’s a person who was extremely deliberative and careful in every single decision that she made.

Yael: Far from it. But she was, she had a fire in her belly to save the people she loved.

Schwab: A fire in her heart, one might say?

Yael: Very poetic. And so I just wanted to throw that in lest we be criticized for spinning fairy tales about her.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: Obviously there are things that you can criticize, but, overall, I find her to be an extremely inspirational figure.

Schwab: Yes.

Yael: And I am glad that the people in Israel in the 1950s decided to make her a national hero because I think we all, and future generations have a lot to learn from her. I mean, she was just good at everything-

Schwab: Yeah. (laughs).

Yael: … which generally when I meet or hear about people who are good at everything, I’m like, “Ugh, gross.”

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: But not here.

Schwab: But she actually was. You know what, she paratrooped back into war-torn Europe to save her mother. So I feel like whatever schoolyard jealousy that I feel towards, like-

Yael: (laughs) those people?

Schwab: Yeah. That the classmate who like, has like the perfect SAT score and is on the basketball team, like, all right, but if they put it to good use, good for them.

Yael: Right. Exactly. Exactly.