Turns out, even Theodor Herzl – as in, the father of the Zionist movement – had briefly considered East Africa in his search for a Jewish state.

How could Herzl – the guy who harnessed the Jewish desire for self-determination into a political movement – even consider an alternative to the Jewish ancestral homeland? How did his fellow Zionists react to his suggestion? And how close did he get to making this “what if” a reality?

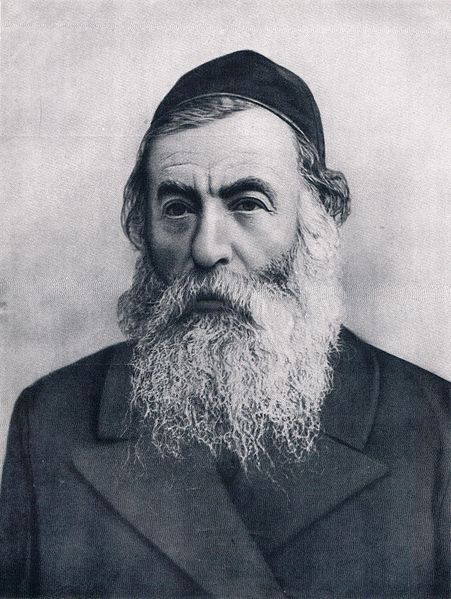

To understand Herzl’s controversial “Uganda Plan,” we’ve got to understand Herzl himself.

Theodor Herzl was born into a wealthy and assimilated Jewish family in 1860. He had everything: private tutors. Piano lessons. An appreciation for German poetry. Basically nothing I had growing up, mom and dad, don’t worry. I’m good.

But even this privileged upbringing couldn’t insulate Herzl from Europe’s antisemitism. As a student at the University of Vienna, he experienced a range of antisemitism – from what we might call “microaggressions” to, you know, regular aggressions. Like quotas on the number of Jews allowed into his fraternity.

After the Dreyfus Affair in 1894 Herzl had his first painful revelation: European Jews would never be safe from antisemitism. As antisemitic parties swept Austrian elections in 1895, Herzl grew increasingly desperate. Listen to his anguish:

“We have sincerely tried everywhere to merge with the national communities in which we live, seeking only to preserve the faith of our fathers. It is not permitted to us. We shall not be left in peace.”

Soon, he came to believe – fervently, obsessively – that only a full-scale Jewish exodus from Europe could bring peace to the Jews.

Where would they go? Their own self-governing state, of course. Easy.

Or not. Gathering the entire Jewish Diaspora in one place would be a challenge. Without Twitter, iPhones, or Clubhouse (ok, Clubhouse isn’t really a thing anymore), how do you get people to move across the world? Plus, the Jewish community was ideologically divided. There is not ONE Jewish community. There are Jewish communiTIES. Could one movement unite assimilationists, revolutionaries, socialists, and rabbis under one banner? Would Asian and African Jews unite with their European brothers?

But there were bigger obstacles than just “two Jews, three opinions.” I mean, check this out. In the late 19th century, the entire world was still largely divided into empires and their colonies: Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, Russian, English. What were the chances of a tiny, mostly-hated (yes, hated) religious minority carving out an autonomous state from a huge empire? (Spoiler: not good.) If there’s anything empires hate, it’s giving away territory to folks who want to govern themselves.

But like me playing NBA Jam on Sega Genesis in 1995, Herzl was on fire. And he wasn’t going to let minor problems like systemic Jew hatred or imperial dominance get in his way. He’d build a home for the Jewish people no matter what. Palestine! Argentina! The Congo! He’d lead the Jews anywhere… as long as they were safe and self-governing.

When he shopped around his idea, Jew after Jew insisted: Palestine or bust. Palestine was the Jews’ ancestral homeland, the object of two millennia of Jewish prayer. The memory of Jewish self-determination lingered in the landscape.

Herzl was convinced. He wouldn’t just build a Jewish homeland, but a Jewish homeland in Palestine. This conviction assured his place among earlier visionaries who called for a return to the ancestral homeland. Leon Pinsker. Rabbi Dr. Yehuda Aryeh Leon Bibas. Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Kalischer. Rabbi Judah Alkalai. But Herzl was the first to turn their dreams into an internationally influential movement.

Less than a year after he laid out his vision in his book Der Judenstaat – translated as either The Jewish State, or The Jews’ State – he was trying to convince the Ottoman sultan to hand some of his territory to the Jews.

But everything changed in 1903.

The Kishinev pogrom shook the Jewish world to its foundation. How could any Jew feel safe in Europe, where a neighbor could smile at you one moment and bury an ax in your skull the next? Where authorities watched… and did nothing?

Europe was a graveyard. And Herzl was determined to get his people out.

So he did something crazy. Something that nearly ripped apart his movement.

At the Sixth Zionist Congress in 1903, he went ahead and officially asked… what if?

What if we made a little stop in East Africa?

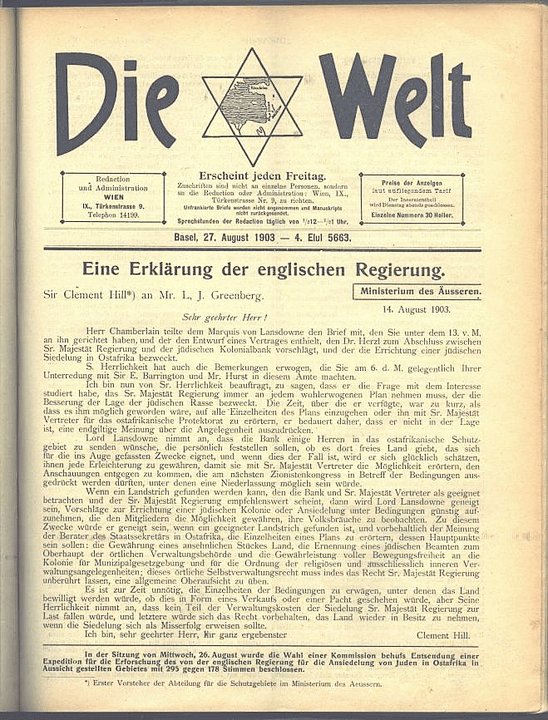

See, Herzl had been wheeling and dealing with some of Europe’s most influential players… including the British Empire. The Brits had offered Herzl a slice of their territory in East Africa. They called it “Uganda.” Today, we know it as western Kenya.

So Herzl asked the Congress: What if the Jews used this territory as a temporary safe haven as they waited to enter Palestine? It wouldn’t be permanent. But just as Moses had wandered with the Israelites for 40 years, Herzl would take whatever detours were necessary to get the Jews to the Promised Land. (Yup. He compared himself to Moses.) He admitted to the Congres that: “[Uganda] does not possess… historical, poetic, religious, and Zionist value… but I do not doubt the Congress will welcome the new offer with warmest gratitude.”

Well, he should have doubted it. Because much of the Congress did not take the proposal well.

The socialists chewed him out.

The Russians – the Russians!, the people most exhausted by violent antisemitism! – declared a hunger strike.

Some religious Zionists scoffed.

Yet Herzl found allies in unlikely corners. The religious Zionist Mizrachi party, led by Rabbi Yitzchak Yaacov Reines, backed the proposal. Rabbi Reines believed that physical safety was paramount. That’s how bad the situation was in Europe. The security of East Africa trumped, even if temporarily, the ancient Jewish dream of Zion.

So when the Congress voted on whether to send an exploratory expedition to Uganda, 295 delegates voted “yes.”

But the 178 diehard idealists who voted NO WAY weren’t going down without a fight. When the results came in, the Russian delegation walked out of the hall. A particularly dramatic delegate went through the motions of shiva – the Jewish mourning ritual. Herzl was called a traitor. The Marxist revolutionary Leon Trotsky – yep, Leon Trotsky was apparently there, because history is totally crazy – declared the end of the Zionist movement.

Herzl pleaded with the naysayers. Promised them he’d do everything in his power to get them to Palestine. And in his final speech to the Congress, he swore – invoking the Bible – “If I forget you, Jerusalem, may my right hand cease to function!” But the damage was done. Well after the Congress, the two camps would sneer at each other in the streets, even going so far as to wish death upon one another.

Before the proposal could tear the whole movement apart, the three scouts returned from East Africa with their report. And the sole Jewish scout among them – Nachum Wilbusch – had grim news: East Africa was totally unsuitable for habitation. Ironically, the territory boasts some of the continent’s most fertile farmland. There’s a strong possibility that Wilbusch had an agenda.

The Seventh Zionist Congress took Wilbusch at his word. In 1905, they voted to kill the Uganda Plan.

Herzl didn’t live to see the Seventh Zionist Congress… or the founding of the state. Still, he was confident in his place in Jewish history. Despite his iconic beard – which I am totally jealous of! – Herzl wasn’t religious. But I don’t think I’m too far off in calling him a prophet. In 1897, he wrote: “At [the First Zionist Congress in] Basel I founded the Jewish State. If I said this out loud today, l would be greeted by universal laughter. In five years perhaps, and certainly in fifty years, everyone will perceive it.”

He was right. Fifty years later, in 1947, the British agreed to a partition plan. Soon after, Ben Gurion declared independence.

We can look back at the short-lived Uganda proposal as both a teasing glimpse into an alternate reality…and as another layer in the Zionist story. Because for Herzl, Zionism was partially about safety. He cared deeply about the physical security of Jewish bodies.

But Zionism isn’t just about safety. And it isn’t just about self-determination, either. Those are components, yes. But as the Russian delegation proved, Zionism is inextricable from Israel and Israel is inextricable from the Jewish people. A Jewish liberation movement cannot be untangled from the Jewish homeland. Jewish history is embedded in every inch of the land. The Zionist movement reconnects us with that history. With that land. With the other exiles who prayed towards Jerusalem for 2,000 years.

Herzl dared to ask what if.

What if there could be a safe haven for the Jewish people? What if it was in Uganda? Or Argentina? Or Palestine?

That’s the most compelling scenario of all: what if an indigenous people came back home? Well, that’s a question that Israel’s 6.8 million Jews answer every single day.