History isn’t just a series of facts strung together in a tidy chain of cause and effect. It’s a shapeshifter, its final form dependent on who’s telling it. Where they start the story. Where they end it. The truths they emphasize and the truths they ignore.

So. Let’s talk about Kishinev.

If history were just a series of facts, here’s what I would tell you.

On April 19th, 1903 – Easter Sunday, and the seventh day of Passover – a mob attacked the Jewish community of Kishinev, a town in what is now Moldova. By the time the riot subsided, 49 Jews had been murdered, some in barbaric ways, and countless Jewish women raped. The pogrom would spark many changes in the Jewish community and beyond, energizing the Zionist movement, horrifying the American government, and even spawning the NAACP.

Simple. Clean. Verifiable. And… completely devoid of life.

None of it would explain why Kishinev – out of all the many, many pogroms of Jewish history – captured the world’s imagination, becoming both a shorthand for Jewish weakness and, almost paradoxically, a call to Jewish action.

And to understand why that is, we have to leave behind the rote recitation of facts and venture into the construction of history, the poetry and propaganda and even a few well-timed lies that spun a myth around a series of facts.

So. Let’s begin.

Welcome to Kishinev

Kishinev, a city in Imperial Russia, was home to 40,000+ Jews, who played a major role in commerce and industry. (In fact, most of the city’s factories were owned by Jews.) Until 1894, life in Kishinev was basically as good as it got for Jews in 19th century Europe. (Which is, yes, a comically low bar.)

But the community’s fortunes turned in 1894, when journalist, ultranationalist, and ardent anti-Semite Pavel Krushevan came to town. Think of him as the ultimate keyboard warrior, who turned the city’s sole daily newspaper into his own personal mouthpiece. Unfortunately, the issue closest to his heart was his all-consuming hatred for the Chosen People. His headlines are like something out of the neo-Nazi website Stormfront. “Death to the Jews!” “Down with the Disseminators of Socialism!” “Crusade Against the Hated Race!” (Yeah, lovely stuff.)

The Russian authorities were disgusted and horrified with his anti-Semitism and did everything they could to stop it. (pause) Haha, just kidding.

The Russian authorities were so tickled by Krushevan’s propaganda campaign that Minister of the Interior Vyacheslav von Plehve approached him about expanding his operation. (Pay attention to this guy, because he shows up again later.) In 1902, with Plehve’s generous backing, Krushevan launched another anti-Semitic newspaper, this one in the tsarist capital of St. Petersburg, so that he could spread his Jew-hatred far and wide.

And, he got his lucky break in early 1903, with the death of two young Christians.

Though one was a murder committed by a family member and the other was a suicide, Krushevan wasn’t about to let the facts get in the way of a good story. With the blessing of the Russian government, Krushevan used his platform to let Kishinev’s Christians know that if they wanted to “execute bloody justice” on the Jewish community, the time to do it was Easter. And because he was fully aware of the power of “fake news,” Krushevan and his cronies used the weeks before the holiday to hand out a pamphlet called “The Rabbis’ Speech,” which detailed a meeting of 12 Jewish elders in a graveyard to solidify their plans for world domination. (You know, you can accuse Krushevan of many things, but subtlety is not one of them.)

The pamphlets and the newspaper headlines worked – and not just in Kishinev itself. People came from all over to participate in the so-called “bloody justice.”

The city’s Jews could read the writing on the wall, and they begged anyone who could help to intervene.

Clergyman to clergyman, the chief rabbi asked the bishop to tell his congregants that the church denounced all forms of blood libel. The bishop responded that some Jews did commit ritual murder, so he couldn’t possibly say otherwise to his flock. The governor was similarly useless, promising the Jewish delegation that he’d done all he could to maintain order. (Listeners: he did nothing.) Worst of all, the Chief of Police told the Jews that a pogrom would serve them right.

The violence began two days later.

In the City of Slaughter

It started with the young people. Verbal harassment, rocks through windows. Then, looting. Destruction of property. Robbery.

The mob was organized, splitting into groups to cover more ground. As they cut a swathe of destruction through the city, they ran into the bishop, who blessed them from his carriage. Their ranks swelled, a microcosm of Kishinev society. Students and seminarians. Policemen and aristocrats. All participated in the rampage and plunder, as it grew bolder and more barbaric.

The next day was Monday, April 30th. The city’s Jews, well aware that the authorities were not on their side, organized defense squads. Hundreds of Jewish men armed with stakes, canes, and even guns guarded property and people alike. But the police – who had done nothing to stop the looting of the day before – broke up the crowd, even arresting a number of Jews.

But even these brave defenders wouldn’t have been able to stop the brutality of the pogrom.

Skip the next two minutes if you don’t want me to completely ruin your day.

A crowd of thousands – thousands – began to beat Jews of all ages and sexes to death with crowbars and clubs – and, in one case, beat a parent to death with their own toddler, before throwing the toddler from a window. They pulled out tongues. Gouged out eyes. Hacked bodies apart with knives and axes. Drove nails through heads and palms and feet, to mimic the crucifixion of Jesus. Cut off women’s breasts. Smashed babies’ heads against walls. Beat pregnant women in the stomach until they died. Or cut them open and stomped on the fetus.

To say nothing of the rapes.

Women and young girls were raped in front of their families, who watched in horror, powerless to stop it. In one exceedingly awful case, a man raped the Jewish woman who had breast-fed him as a baby.

The rioters trashed synagogues. In at least one instance, they tore up and soiled Torah scrolls as the community tried in vain to protect them.

To make a brutal story short: Kishinev was Auschwitz before Auschwitz. Or, in the words of Steven J. Zipperstein in his book Pogrom: Kishinev and the Tilt of History, “Prior to Buchenwald and Auschwitz, no place-name evoked Jewish suffering more starkly than Kishinev.”

To be sure, the suffering I’ve detailed above is… indescribable.

There’s no way for me to exaggerate it, no way to present it other than to say it straight, as factually and unemotionally as possible. No way to turn it into anything but what it is.

Then again, I’m not Chaim Nachman Bialik.

The Poet and the Journalist

Though I’ve just detailed acts of barbarity that seem to belong in the Dark Ages, remember that the pogrom took place in 1903 – only 120 years ago, fully in the age of cables and photographs, of information sent halfway across the world with unprecedented speed. And the photographs that accompanied every newspaper headline were so shocking that people began to question if they were real.

Historian Simon Dubnow, head of the Kishinev Historical Commission, had no doubt that the photos were real. In fact, he wanted more – as much evidence as he could muster, should the murderers ever be brought to trial.

And the man who would collect this evidence?

One Chaim Nachman Bialik, later crowned the Jewish world’s national poet. Though Bialik’s first book of Hebrew poetry had already earned him no small degree of fame in certain circles, it was his account of the pogrom in Kishinev that would turn him – and the pogrom itself – into an icon.

For over a month, the 30-year-old collected evidence, eventually filling four notebooks with his findings. And yet, only the most brutal, gruesome testimony found its way into his account of the massacre, which took the form of a poem he called B’Ir HaHariga, In the City of Slaughter.

Bialik’s Hebrew is dense, heavy with allusion to Talmudic and Biblical sources. Though the English translation can’t approach the power of the original, it’s nonetheless shocking. Here it is:

…do not fail to note,

In that dark corner, and behind that cask

Crouched husbands, bridegrooms, brothers, peering from the cracks,

Watching the sacred bodies struggling underneath…

…Come, now, and I will bring thee to their lairs

The privies, jakes and pigpens where the heirs

Of Hasmoneans lay, with trembling knees,

Concealed and cowering,—the sons of the Maccabees!

The seed of saints, the scions of the lions!

Who, crammed by scores in all the sanctuaries of their shame,

So sanctified My name!

It was the flight of mice they fled,

The scurrying of roaches was their flight…

You don’t need a degree in poetry to parse Bialik’s disgust. Look how he describes Kishinev’s victims: “crouched” men watching helplessly as their loved ones were raped. “Concealed and cowering” Jews in the “sanctuaries of their shame,” fleeing like “mice” and “roaches” from the slaughter.

Jewish history is full of similar pogroms and tragedies. But generally, in the lamentations and poems about those tragedies, the victims are lionized as martyrs for a holy cause. Heroes who died for the sake of their faith and their people. Bialik’s poem painfully inverted that paradigm. In the words of Israeli philosopher Micah Goodman: “Perhaps for the first time in Jewish history, the victims were not holy – they were repugnant.”

Tellingly absent is any mention of the self-defense or resistance that Bialik himself had documented in his notebooks. And to be clear, he wasn’t LYING in this poem. He was just focusing on one …angle of truth, you might say. See, as an ardent Zionist, Bialik was very well aware that if he wanted to rouse the Jewish world to action, he had to emphasize — viscerally, painfully — the very worst indignities of the diaspora. Only then would the Jewish people realize that their futures lay in Eretz Yisrael.

So began the myth of Kishinev. The power of the well-chosen word transformed the Jewish imagination and the course of history. Religious and secular Jews alike found deep import in the poem. The rabbi of Moscow announced that B’Ir HaHariga should replace more traditional kinnot, or lamentations, recited in synagogues. And after Bialik himself translated his poem into Yiddish so that it could reach the widest possible audience, the poem became a rallying cry for Jewish self-defense.

But Bialik’s was not the only account in town. A far more unlikely source publicized the event in the Western world.

As a radical Irish nationalist and journalist for the newspaper The New York American, Michael Davitt was an unlikely choice to verify the accounts coming out of Kishinev. In the words of Dr. Steven J. Zipperstein, Professor in Jewish Culture and History at Stanford University, Davitt “felt great antipathy for those responsible for the massacre… [but] also saw Jews themselves as fanning discontent, or worse.”

But a job was a job, and Davitt was a painstaking and thorough journalist who chased down even the smallest details, even as rumors and “fake news” swirled about. People were so doubtful; surely the riot couldn’t have been as bad as all that. Surely those harrowing photographs had been doctored? Maybe the Russian government was correct in blaming the whole affair on a couple of young hooligans, and even on the Jews themselves.

So despite his uneasy relationship to Jews, Davitt came to set the record straight. And, as Dr. Zipperstein said, “he placed blame for the pogrom… squarely on the shoulders of Pavel Krushevan.” Though Davitt wrote in his personal notebook that “Jewish men… acted as contemptible cowards,” this detail was absent from his official account.

Davitt’s meticulous recounting of the pogrom made him into a “folk hero” of the Jewish community. One play written about the riot calls him (or the fictionalized version of him) “the truest, dearest friend our people ever had.”

Two accounts of the riot. Both entirely different. Both entirely true. Behold the construction of history.

The Aftermath

So now we have two narratives. Bialik’s, which showed groveling, cowering Jews, and Davitt’s, blaming Krushevan for the evil perpetrated in Kishinev. Both are true. Both are also completely different in their thesis and their aims.

Galvanized by these accounts, Jews were spurred into action, and quickly mobilized. In Vilna. In Kiev. Odessa. In St. Petersburg, where a young Jew tried (but failed) to assassinate Krushevan.

And of course, in Palestine. As new immigrants arrived from Europe bearing tales of unbelievable savagery, Jews in Palestine formed self-defense groups that would eventually morph into the Haganah. This paramilitary squad, as you know from last week’s episode, would later become the Israeli army.

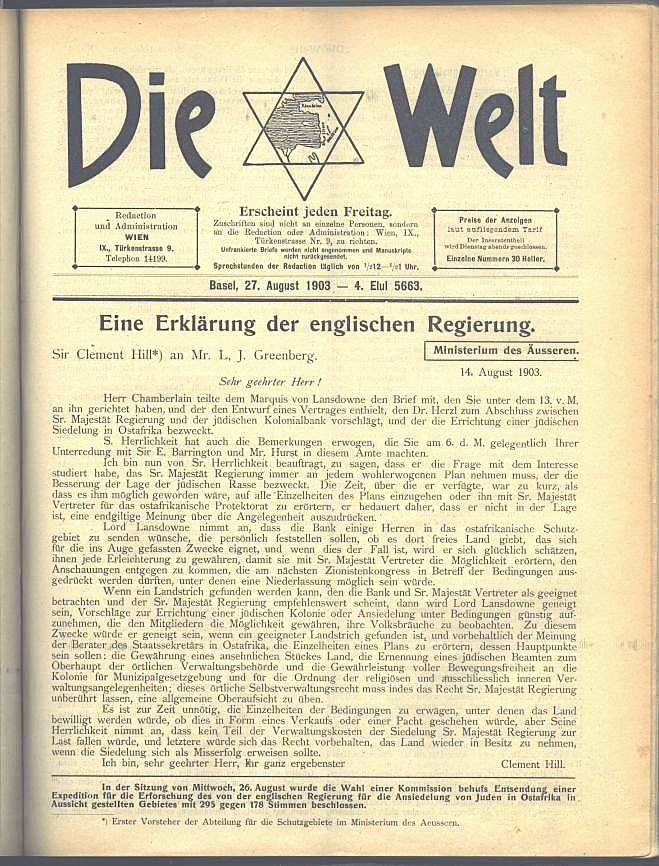

For the Zionist movement, Kishinev exemplified the worst of the Diaspora. Only Zionism – and with it, a new, strong breed of Jew – could end the suffering. Theodore Herzl opened the Sixth Zionist Congress in 1903 with the words, “Kishinev exists wherever Jews undergo bodily or spiritual torture, wherever their self-respect is injured and their property despoiled because they are Jews. Let us save those who can still be saved!”

And then he did something highly controversial. He brought up the possibility of the Uganda Plan. See, the Zionist movement was founded on the idea of a Jewish return to the ancestral homeland in Palestine. But Europe’s Jews needed help now. Though Herzl believed with every fiber of his being that Palestine was the Jews’ only true home, he proposed the possibility of Uganda as a temporary sanctuary, a safe way station between Europe and Palestine. (Check out our Season 1 episode entitled Herzl and the Non-Promised Land for more details on the Uganda Plan.)

But before the suggestion could totally rip apart the Zionist movement, the British rescinded their offer of Uganda, and the Zionist leadership redoubled its focus on Palestine.

Meanwhile, Americans, too, mobilized on behalf of Kishinev’s Jews. Their efforts went all the way to the top; after much pressure from Jewish groups and against the advice of his ambassador to Russia, even President Theodore Roosevelt blamed the Russian government directly for the Jews’ miserable situation, and called for increased toleration.

I don’t want to shock you too much, but the Russians ignored him.

Still, the Russian government had unwittingly handed America’s Jews a serious victory only weeks after the pogrom. It appeared that Minister of the Interior Plehve – yes, the same guy who financed Krushevan’s anti-Semitic newspaper in St. Petersburg – had written a letter, dated before the pogrom, that explicitly instructed the authorities to do nothing to quell the violence.

Here was proof that Russian-Jewish life was intolerable, that the government itself sought to destroy its Jews. The infamous Plehve letter proved a highly effective defense against American immigration restrictions. Between 1900 and 1914, a staggering 1.5 million Eastern European Jews emigrated to the United States.

There was only one problem.

The Plehve letter was a fake.

Oh, there was no doubt that Plehve hated Jews. And it was also true that the authorities had waited a good long time before they stopped the bloodbath.

But anyone who knew Plehve knew he hated public disorder. And there was no evidence whatsoever that he had written that letter. But the Russian government’s denials only served to further convince people of the letter’s authenticity. Even Leo Tolstoy spoke out.

Thus a well-timed lie shaped the course of history. The Plehve letter – aided, no doubt, by a series of subsequent pogroms – proved to Jews that the situation in Russia was intolerable. By 1920, more than a third of Russia’s Jews had emigrated – mostly to the United States and Palestine – indelibly transforming both.

It’s not surprising that Jews would flee the country after a government-sanctioned pogrom. What is surprising, though, is the effect of Kishinev on another minority community: Black Americans.

When news of Kishinev broke, dominating the news cycle, Black and Jewish Americans alike drew explicit parallels between anti-Black violence at home and anti-Jewish violence abroad. Lynching and pogroms were essentially different words for the same thing. And as more pogroms followed on Kishinev’s heels in 1905 and 1906, American activists, Jewish and non-Jewish alike, publicly conflated attacks on Jews in Russia to attacks of Black Americans, emphasizing America’s racial injustices. Six years after Kishinev, a multi-racial coalition, including a Jewish immigrant from Russia, founded the NAACP. How’s that for intersectional politics?

But perhaps the most striking – if unsurprising – reaction to Kishinev was from the Russians themselves. Or more specifically, from, you guessed it, Pavel Krushevan. Proving there was no end to his chutzpah, Krushevan solidified his most enduring legacy just months after the massacre. He was the very first to publish The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.

Now, in case you’re lucky enough to be unfamiliar, let me destroy your blissful innocence: the Protocols is the granddaddy of anti-Semitic conspiracy theories. It purports to be a transcription of a series of meetings of the so-called “Elders.” You know, the Jewish cabal intent on destroying governments; controlling the media and the banks; fomenting major conflicts around the globe; enslaving non-Jews; and ruling the world with an iron fist.

These fabrications are so ludicrous that they’re almost funny. (Seriously. Spend 10 minutes at a synagogue board meeting, and then try to keep a straight face while you tell me that the Jewish community is organized enough to pull all of this off.)

But unfortunately, the Protocols are the ultimate tool in the anti-Semite’s arsenal. And Krushevan was the first to publish them, further fomenting Russia’s already-robust anti-Semitism and proving – once again – the world-altering power of fake news.

So that’s the story of Kishinev, and here are your five fast facts:

- Kishinev is perhaps the most famous pogrom in the Jewish imagination. Not because of its death toll, or savagery, or because of the encouragement from local authorities, none of which, sadly, were new. No, Kishinev’s notoriety demonstrated a couple of things. The first is the power of the photograph, which displayed the savagery plainly. And the second is that the way you tell a story is just as important as the facts you recount. The event was best memorialized in the Jewish world by a wrenching poem called B’Ir HaHariga, whose depiction of Jews as cowards and weaklings was responsible for the formation of Jewish self-defense leagues in Europe and beyond – the most famous of which, the Haganah, would later become the Israeli Defense Forces.

- The Kishinev pogrom took place largely due to the efforts of Pavel Krushevan, whose anti-Semitic newspaper headlines and pamphlets stoked a deep and violent hatred of Jews. After nearly a decade of Krushevan’s incitement, the people of Kishinev spent Easter of 1903 taking revenge on the Jews for offenses that Krushevan and his cronies had invented. Local authorities did nothing to stop the brutality, and some even participated in it.

- The pogrom so horrified Theodor Herzl that he proposed the controversial Uganda Plan at the Sixth Zionist Congress. (Seriously, check out our Season 1 episode on Uganda!) The proposal was highly controversial and ultimately fruitless, as the British eventually rescinded the offer of Uganda.

- Kishinev changed American demographics. Though President Theodore Roosevelt condemned the massacre, he stopped shy of making any policies that actively encouraged Jewish emigration from Russia. However, the Jewish community was able to block proposed immigration restrictions, due in no small part to a letter from the Russian Minister of Interior that proved the government’s involvement in the pogrom. This letter, however, turned out to be a forgery.

- The ongoing press coverage of Kishinev spurred American liberals – Black and white alike – to consider the many parallels between Russia’s Jews and America’s Black community. In fact, many Jewish activists explicitly connected anti-Jewish pogroms in Europe with anti-Black lynchings in America. As Kishinev dominated the news cycle, the Black community pressed for increased protection at home, establishing the NAACP in 1909 to promote Black civil rights.

Those are the five fast facts, but here’s one enduring lesson as I see it.

Despite its relatively low death toll, especially compared to the massacre of over 100,000 Ukrainian Jews between 1918 and 1921, the Kishinev pogrom is the one we remember. And not just because of the facts of the pogrom – the rapes, the brutality, the looting. Kishinev came at a crucial moment in Jewish history, between the pogroms that ripped through Russia in the 1880s and the formation of an organized, political Zionist movement. But as the story spread, it took on new and terrible dimensions. In the wake of the devastation, more and more Jews came to agree with Zionist thinker Ahad H’Am, who said “It is a disgrace for five million human souls to unload themselves on others, to stretch their necks to the slaughter and cry for help, without as much as attempting to defend their honor and their lives.” Jewish safety, Jewish self-defense, and eventually Jewish self-determination became the paramount priority.

But it took Bialik’s castigations in B’Ir HaHariga – his portrayal of the victims as pathetic, weak, corrupted by millennia of exile – to inspire the global Jewish community to reclaim its former status as heroes and Maccabees.

At the same time, as Bialik’s poem solidified the myth of Kishinev and attracted more and more Jews to the Zionist cause, the world’s most enduring piece of anti-Jewish propaganda was born. It, too, reshaped the course of history, reinforcing a much darker myth about the Jewish people.

So what do we do with this? What does it all mean?

I don’t have a great answer to this. But I can’t help but consider the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. As I doomscroll through increasingly grim headlines, I think about the Ukrainian Jews of 120 years ago. Jewish history in Ukraine is rich and ancient and complex. Ukraine is the birthplace of Hasidism, the home of a once-great Yiddish culture. And it was home, too, to so many early Zionists. I think about these men and women, how they dared to dream of a state of their own, free of state-sanctioned antisemitism. How so many died, and in such awful ways, before that dream came true.

And I think about the fact – the miracle! – that there is a Jewish state to welcome all Jews who have no home, no shelter, no security. A NYT article from March 8, 2022, highlights this perfectly. The headline? “Once Victims in Southeast Europe, Jews Come to Aid Fleeing Ukrainians.” And it reports something incredible, that in the town of Kishinev itself – now situated in Moldova – Israelis are helping thousands of Jewish and non-Jewish refugees evacuate to Israel. PM Naftali Bennett said: “In the same Kishinev, right now, we’re saving Jews. The raison d’être of Israel is to be a safe haven for every Jew in danger. We didn’t have it in 1903. We have it now.”

We have it now.

I think about Bialik, pouring his shame and disgust into his poetry. In 1903, could he have imagined Jewish people who are not cowering, but saving? It’s a rhetorical question, of course. I like to think about him writing a sequel to B’Ir HaHariga. Maybe he’d call it B’Ir HaMiklat. In the Sanctuary City, where Jews wait for their brothers and sisters with open arms, ready to bring them to safety.

I’ll end with a blessing. Let’s remember Kishinev, but let our identities not be defined by Kishinev.