Editor’s note: This article is part 2 of a three-part series on Israel’s presence in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

Read part 1 on how Israel gained control over the West Bank and Gaza in 1967, which provides key context for this article, and part 3 on whether Israel is occupying the Gaza Strip.

Many statements and articles about the Israel-Hamas war refer to the West Bank and Gaza Strip as “the occupied Palestinian territories,” but is Israel really occupying the West Bank? Let’s unpack this big question, starting with the definition of “occupation” in international law.

What is occupation?

Under international law, occupation is defined as territory that is “placed under the authority of the hostile army. The occupation extends only to the territory where such authority has been established and can be exercised.”

In its commentary on the Geneva Conventions — a key collection of international laws setting the rules of war — the International Committee of the Red Cross states that a territory is considered occupied when military control is implemented without the host state’s consent. This can occur even if control is implemented without violence and only through a show of force.

Occupying powers are subject to several restrictions and responsibilities under international law. This includes prohibitions against forcibly transferring their own civilian population into the occupied territory, as well as forcibly relocating people from within the occupied territory to other areas.

They are also obligated to maintain public order and safety and ensure that civilians’ basic necessities are met, allowing them to lead their lives as normally as possible under the circumstances.

Is Israel occupying the West Bank?

As with many issues in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, it depends on who you ask. Let’s answer the question from various angles.

The Jewish connection to the land

One critical factor in answering the question is the Jewish historical connection to the land.

The Jewish people have had a continuous presence in the land of Israel — including Judea and Samaria (commonly known as the West Bank) — for thousands of years, making them native and indigenous to this land.

Judea and Samaria are not merely geographical terms but are deeply ingrained in Jewish history, religion and identity.

The Jewish historical ties to Judea and Samaria date back to ancient times, long before the establishment of modern states.

These regions are integral to biblical narratives and Jewish history as the heartlands of the ancient Jewish kingdoms. Cities like Hebron in Judea were among the oldest Jewish communities, and key religious sites such as the Tomb of the Patriarchs are deeply revered in Jewish tradition.

Recognizing this historical connection is crucial in understanding the Israeli perspective in the conflict.

While the land is deeply Jewish, the question of “occupying Palestinian people” is more nuanced. The Israeli presence in these areas reflects a complicated mix of security measures, administrative control, and cohabitation with Palestinian residents (read more on all of this below).

This reality reflects a challenging balance between historical claims and contemporary political considerations.

In light of this, author Yossi Klein Halevi characterized Israel’s presence in Judea and Samaria (the West Bank) this way: “I don’t believe we are occupiers in any part of the land of Israel. But we are occupying the people with whom we share the land.”

Historical arguments

Another crucial factor is the history of how Israel came to gain control over the West Bank in the first place. Israel captured the West Bank, Gaza Strip, East Jerusalem, the Golan Heights, and the Sinai Peninsula in the Six-Day War of 1967.

The Six-Day War was a watershed moment in the region’s history, reshaping the geopolitical landscape as well as narratives and perceptions of the conflict.

When Arab forces lined up along Israel’s borders in 1967, openly threatening its annihilation and greatly outnumbering Israeli forces, the Jewish state responded with a preemptive strike.

Within six days, Israel not only pushed these armies back but gained control over new territories, tripling its size practically overnight.

It was after this war that the term “occupation” became commonly used in reference to Israel’s control of the West Bank, Gaza (which Israel withdrew from in 2005), and the Golan Heights.

Israel’s capture of these territories created intense resentment in the region, with Palestinians referring to the war as the “Naksa,” the setback.

Three months after the Six-Day War, Arab leaders declared their “Three No’s”: “No peace with Israel, no recognition of Israel, and no negotiations with Israel.”

Read more about how Israel initially captured the West Bank and Gaza.

In Israelis’ eyes, the Jewish state had fairly won control of these territories in a defensive war.

This has implications for whether Israel is an “occupier” of the West Bank. In his book “Catch 67: The Left, the Right, and the Legacy of the Six-Day War,” Micah Goodman captures the nuances of the situation:

“On the one hand, the territories are not stolen land that came under Israel’s control by immoral means, so they are not in themselves occupied. On the other…Israel imposes a military rule on a Palestinian population that has no say over the state’s decisions, so the Palestinians are a nation that lives under occupation. The conclusion is that the territories are not occupied, but the Palestinian people are.” (page 104)

This perspective reflects a critical distinction between the land itself — with its ancient Jewish connections and captured by Israel in a defensive war — and the complex realities of governing a Palestinian population in some parts of the West Bank.

Legal arguments

Israel’s Foreign Ministry maintains that the establishment of Israeli settlements in the West Bank does not violate international laws prohibiting forced population transfers into or out of occupied territories.

They argue that settlements are not the result of forced population transfers but rather are voluntarily established by individuals.

Additionally, the Ministry argues that the lands on which these settlements are built were not under the legitimate sovereignty of any state prior to Israel’s control and are not privately owned.

The ministry also highlights the historical Jewish connection to the land and argues that the West Bank’s status as part of a Jewish state under the League of Nations, combined with its capture in a defensive war, challenges the application of the Geneva Convention on occupation.

“In legal terms, the West Bank is best regarded as territory over which there are competing claims which should be resolved in peace process negotiations — and indeed both the Israeli and Palestinian sides have committed to this principle,” the Foreign Ministry wrote in 2015.

“In legal terms, the West Bank is best regarded as territory over which there are competing claims which should be resolved in peace process negotiations.” — Israeli Foreign Ministry

Eugene Kontorovich, an international law scholar, supports Israel’s claim, arguing that Israel cannot be considered an occupier due to its historical and legal ties to the land.

He notes that the League of Nations Mandate included the West Bank and was the last internationally recognized authority over the land before Israel’s founding.

Kontorovich also cites a 1978 U.S. State Department memo suggesting that Israel’s post-1967 occupation status would end with a peace treaty with Jordan, which occurred in 1994.

Conversely, the Israeli Supreme Court maintains a different stance. In a 2005 case, the court described the West Bank as under “belligerent occupation.”

This view has been reflected in several cases, although the application of international law by the court in these matters is sometimes debated among legal experts.

Security concerns

A key factor in Israel’s approach to the West Bank is its security concerns, which are significantly shaped by both current reality and past experiences. A critical example is Israel’s unilateral disengagement from the Gaza Strip in 2005.

Israel withdrew all its settlements and military presence from Gaza, with the intention of paving the way for peace. However, following this withdrawal, the Gaza Strip fell under the control of Hamas, an organization designated as a terrorist group by Israel, the U.S., and the European Union.

Hamas has since used Gaza as a base for launching rocket attacks against Israeli cities, significantly impacting Israel’s security situation. On October 7, it launched an unprecedented attack on Israel, killing 1,200 people, kidnapping 240 people, and injuring thousands of others.

This ongoing reality deeply influences Israel’s approach towards the West Bank. Israeli policymakers argue that a complete withdrawal or the relinquishing of military control without a reliable peace agreement could lead to a similar situation in the West Bank, potentially exposing central Israeli cities to greater security risks.

Israel’s concern is that without its military presence, the West Bank could become a base for hostile activities by groups like Hamas or Islamic Jihad, posing a direct threat to its citizens.

Therefore, while the international community and Palestinian leadership view Israel’s continued control over the West Bank as an unjustified “occupation,” Israel defends its actions as necessary for national security.

The Israeli government maintains that any change in the status quo in the West Bank should be achieved through bilateral negotiations, ensuring that Israeli security concerns are adequately addressed in any future peace agreement.

Israel’s presence in the West Bank

Since 1967, the West Bank has been under Israeli military administration. Israeli law is applied to Israeli citizens in the area, but Palestinians are not Israeli citizens and do not enjoy the same legal protections.

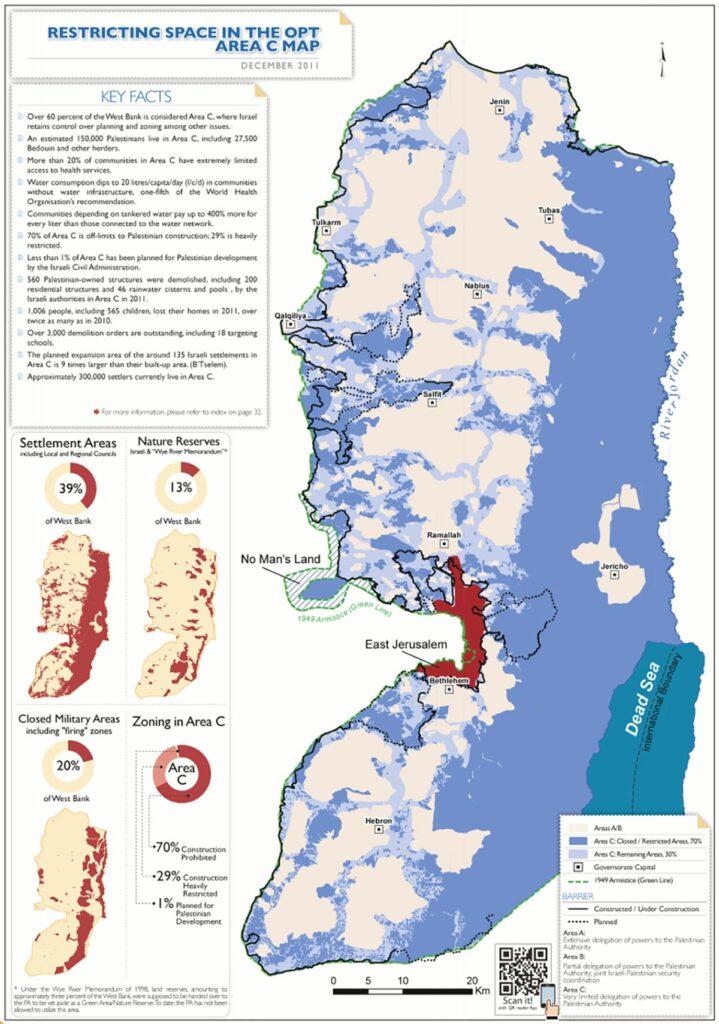

Under the Oslo Accords, signed in the 1990s between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), the West Bank was divided into three areas: “A,” “B” and “C,” with varying degrees of Palestinian Authority (PA) and Israeli control:

- Area A is completely under PA control

- Area B is under PA civil control and joint PA-Israel security control

- Area C is under Israeli security control and administered by an Israeli military administration.

The vast majority of Palestinian residents in the West Bank (90%) live in areas A and B, which are under Palestinian civil control.

Arabs who live in Area C of the West Bank are subject to different laws than Israeli citizens. These laws include the restriction of movement and search and seizure of property.

Much of the international community argues that Israel is an occupying power because of this reality. They point to Israel’s military presence and control of Area C, as well as restrictions placed on Palestinian residents.

However, the Israeli government maintains that the West Bank is disputed territory rather than occupied land, with many areas subject to continued negotiations.

Israeli officials argue that any change in the status quo should come through bilateral peace talks, as outlined in the Oslo Accords. These negotiations would address both Israeli security concerns and Palestinian aspirations for statehood.

Historical attempts to resolve the conflict

Since 1967, there have been several attempts to achieve a peaceful resolution to the Arab-Israeli conflict, including the Camp David Accords, the Madrid Conference, the Oslo Accords, and the 2000 Camp David Summit.

The Camp David Accords of 1978 laid the groundwork for the Egypt-Israel peace treaty signed soon after, but did not directly resolve the Palestinian issue. The rest of these attempts were unsuccessful due to rejection by the Palestinians.

Each of these initiatives, had they been successful, would have significantly altered the nature of Israel’s presence in the West Bank.

Conclusion

The question of whether Israel is occupying the West Bank is complex and multifaceted, involving historical claims, legal interpretations, and security considerations.

While the international community often perceives Israel’s presence in the West Bank as an unjustified occupation, Israel defends its actions as necessary for national security and backed by historical and legal claims.

Ultimately, the answer to the question, “Is Israel occupying the West Bank?” is nuanced. In terms of the land itself, considering the historical Jewish connection and how Israel gained control of this territory, the answer is no.

The question of whether Israel is occupying the Palestinian people is more complicated, and in many ways, the answer is yes. These nuances make the issue a central and contentious point in the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Why does it matter whether Israel is an “occupier”?

The question of whether Israel is considered an occupying power has implications for its legal obligations to Palestinians under international law — and not only that.

If Israel is considered an occupying power, it bears greater responsibilities for the everyday needs of the residents in those territories, including providing essential services like food, medical supplies, clothing, and housing.

Beyond the legal ramifications, the terminology used in this context profoundly impacts perceptions of the conflict.

Labeling Jews as “occupiers” falsely presents them as foreigners with no historical ties to the land, usurping it from its original inhabitants.

Such a narrative overlooks the deep and enduring connection between the Jewish people and the land, while attributing exclusive rights to Arab Palestinians and undermining Jewish historical claims.

For instance, a U.N. report on Palestinian self-determination promotes this narrative. It consistently labels Arabs as “indigenous,” implying that Jews are not native to the region and diminishing their historical bond with the land.

Additionally, since the attacks of October 7, anti-Israel protests around the world have frequently portrayed Israel and the Jewish people as foreign occupiers or colonizers.

Such characterizations delegitimize Israel’s existence, the Jewish connection to the land, and the Jewish right to self-determination in their homeland.

Recognizing the Jewish historical connection does not invalidate the Palestinians’ ties to the same land.

Many Israelis recognize and accept the Arab heritage in Israel, as evidenced by repeated efforts for a two-state solution like the U.N. Partition Plan and the Oslo Accords, both of which were rejected by the Palestinians.

The use of terms like “occupation” and “colonization” — especially when they dismiss Jewish heritage — can significantly impact policy decisions and incite antisemitism and violence in the region and around the world. These terms simplify a complex situation and can have far-reaching consequences.

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel explained the impact of language this way: “Speech has power. Words do not fade. What starts out as a sound, ends in a deed.”

Considering these factors and acknowledging the complex history and legal arguments, it is inaccurate and dangerous to label Israel as “an occupying power.”

A more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of the conflict is essential. This understanding should respect both the Jewish historical connection to the land and the rights and aspirations of the Palestinian people.

It’s only through this balanced perspective that a more constructive and peaceful dialogue can emerge, paving the way for potential solutions to this longstanding conflict.

Read more: Is Israel occupying the Gaza Strip?

Originally Published Dec 6, 2023 06:09PM EST