Have you ever had a juicy secret? The kind that’s so explosive, you can’t even tell your closest friends? And then, when you finally do tell them, everyone’s got an opinion? Well, that’s the story I’m telling you today.

This story is about two sworn enemies who had spent nearly 50 years at war. A war so ugly that the two sides refused to even acknowledge each other. But this isn’t a story about how much these enemies hated each other. Quite the opposite. It’s a story about the time these two enemies tried to work out their differences. And it’s about what happened when the world found out.

Yup, I’m talking about Israel and the PLO, and the time they met up in the unlikeliest of places and tried to find a path to peace. It’s a tough, divisive story to tell. But I hope I can tell it without alienating every single person watching. Let’s find out.

Our story starts in 1964 with the creation of the Palestine Liberation Organization, or PLO — the “unified embodiment of the Palestinian national movement.” Through the 60s, 70s, and 80s, the PLO’s M.O. was international terrorism. They hijacked planes. Took hostages. Murdered Olympic athletes just because they were Israeli. And on, and on. In short, the PLO was Israel’s worst enemy. And in a region full of enemies, that’s saying something.

Things got even worse in 1987, with the start of the First Intifada, the Palestinian popular uprising. Riots, stone-throwings, stabbings, shootings, Molotov cocktails, grenades, and bombs became a daily reality for Israelis. For three years, teenage soldiers were given the thankless, impossible task of containing the frustration and unrest in Gaza and the West Bank.

It was a dark, dark time. The nightly news broadcast images and video of the Intifada, and the world responded with sympathy for the Palestinians.

But something changed in 1990. Something very strange and unexpected. PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat made a huge mistake. He sided with Saddam Hussein in the Gulf War.

What does an Iraqi dictator have to do with Yasser Arafat? A lot, actually. Suffice it to say that Arafat had backed the wrong horse, ticking off the Western world and alienating the Gulf States, who were the PLO’s biggest donors. The PLO was broke and desperate. With their backs to the wall, they had no choice but to start making nice with Israel.

And Israel, which was sick and tired of what felt like a never-ending cycle of violence, was also ready to start shaking hands and making nice. American President George H.W. Bush jumped at the prospect of bringing peace to the Middle East.

He and Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev worked hard to bring Israel and its Arab neighbors — Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and the PLO — into the same room at the 1991 Madrid Peace Conference. Yep, that’s right. America and the Soviets, working together. If those two enemies could make peace, surely they could solve the Arab-Israeli conflict?

Spoiler alert: they couldn’t and they didn’t. But the Madrid Peace Conference was still important — it was the first inkling that things could change between Israel and the PLO.

More changes followed. In 1992, Israelis voted out Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir, and voted in his defense minister, Yitzhak Rabin. Rabin was a giant in Israel. The celebrated war hero of 1948 and 1967, Rabin had already served a term as prime minister back in the 70s. He’d authorized the daring raid on Entebbe. Begun brokering peace with Egypt in 1975. He was the perfect leader to usher in a new era of peace with the Palestinians.

But he couldn’t do it alone. Half a world away, in the most unlikely place, a pair of idealists also dared to dream of a new Middle East.

Professor Terje Rød-Larson and his wife Mona Juul — the future Norwegian ambassador to Israel — had been working in the Middle East for a long time. They had lots of contacts in the region. And more importantly, they had the vision and the chutzpah to bring together Israelis and Palestinians on neutral ground: Oslo, Norway.

So, as snow fell on Norway’s frozen capital, Terje and Mona introduced two sworn enemies. The meetings between Israelis and Palestinians were capital-S SECRET. The director of the Mossad, Israel’s famous intelligence agency, only learned about the talks from a bugged chair he had placed in Mahmoud Abbas’ office. (Yes, that’s the same Mahmoud Abbas who was elected president of the Palestinian Authority in 2005.)

You can’t make this stuff up. It didn’t take long for the secret to come out. By 1993, the world knew all about the secret meetings in Oslo. And something insane happened.

Israel and the PLO agreed to recognize one another. If this doesn’t sound like a big deal to you, let me just stress again: these people are enemies. Arafat had led the PLO through some of the worst terrorist attacks in Israel’s history! Meanwhile, Rabin had tried to put down the First Intifada with an “Iron Fist.” The two leaders were separated by decades of blood and mistrust.

Yet here was Arafat saying that Israel had a “right to exist in peace and security,” renouncing terrorism, and promising to revoke some of the more, ah, violent parts of the PLO charter. And here was Rabin recognizing the PLO as the representative of the Palestinian people and agreeing to negotiate with them.

Just a few years prior, the Israelis wouldn’t have even sat in the same room as the PLO. And now the prime minister was writing letters of recognition to the PLO chairman!

But recognition was just the first step. After that, it was time to set some ground rules. In September of 1993, Rabin and Arafat signed the Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements… AKA the Oslo Accords.

Here’s what they established:

- There would be a democratic Palestinian government in the West Bank and Gaza. If this government could keep it together for five years, it would be replaced by a more permanent government structure.

- The Palestinians would manage their own infrastructure in the West Bank and Gaza for the first time. Hey, someone has to make sure the lights stay on and the sewage stays out of the street!

- Israel would withdraw from the Gaza Strip and parts of the West Bank, starting with the ancient city of Jericho.

It all sounds kinda boring, doesn’t it? Especially all the infrastructure stuff. I actually almost fell asleep saying it. Turns out peace was a lot less glamorous than it sounds.

But think about it for a second. The Palestinians had never had their own seaport. Their own electric authority. They’d never had the chance to govern themselves. To be in control of their own economy. To maintain some sense of sovereignty over their own borders. In short, they’d never had a country. These boring-sounding, mundane things — a sea port, an electric authority — were stepping-stones to actual Palestinian independence.

Which meant that Israelis and Palestinians alike freaked the heck out. Private citizens. Political leaders. Journalists. Economists. Everyone had something to say.

Many Israelis wondered if the government had lost its mind, believing, in the words of author Yossi Klein Halevi, that “nothing would come out of this pretend peace except blood.” The PLO and Hamas were working together, warned Rabbi Yoel Bin-Nun, one of the leaders of the Religious Zionist movement. He wasn’t entirely wrong.

Just eight months after signing the Declaration of Principles, Arafat gave quite the disturbing speech at a mosque in South Africa. Among other things, he asked the audience to “come and to fight and to start the Jihad to liberate Jerusalem.” Not that Hamas and Islamic Jihad needed any encouragement. Beginning in 1993, they unleashed a wave of terror on Israelis. Stabbings and suicide bombs became the new, horrible norm, killing nearly 300 Israelis between September 1993 and September 2000.

Within Israel, protests raged. Bumper stickers called for “the criminals of Oslo” to be “brought to justice.” Some extremist demonstrators carried posters of Rabin dressed as an SS officer. In the West Bank, Palestinians burned pictures of Arafat.

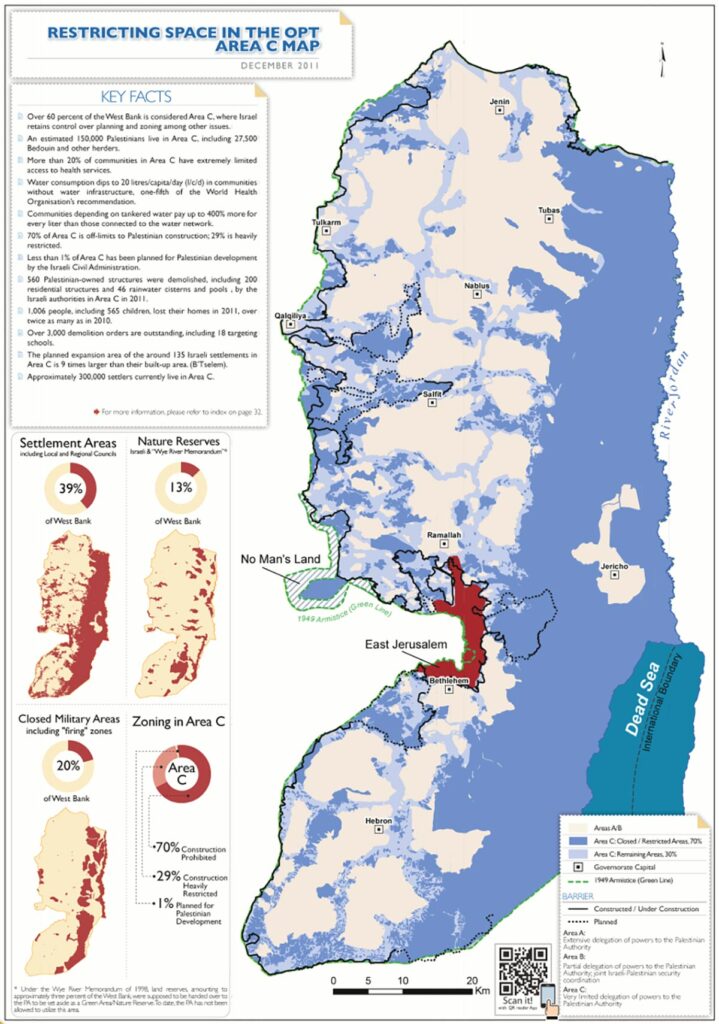

But the two leaders soldiered on. In 1995, they met in Taba, Egypt, to sign a new set of accords, known as Oslo II. This agreement divided the West Bank into three areas, creatively named Areas A, B, and C.

Area A, which comprised six major Palestinian cities in the West Bank — like Ramallah and Jenin — would be run entirely by the Palestinians.

Area B, which in 1995 was home to roughly 68% of West Bank Palestinians, would be governed entirely by the Palestinian government. However, Israel would be in charge of security.

Area C, which was home to few Palestinians and many Israelis, would be controlled mostly by Israel, though the Palestinian National Council would be responsible for things like healthcare and education in Palestinian areas. But the sacred city of Hebron, which houses the Tomb of the Patriarchs, would remain under Israeli control.

Finally, the agreement mandated that Israel release an unspecified number of Palestinian prisoners in three stages.

Like its predecessor, Oslo II was highly controversial. In the Israeli Knesset, the second set of accords passed with the thinnest of margins: 61 for, 59 against. Many of the “ayes” came from the Arab anti-Zionist parties. (Yes, there are Arab anti-Zionist parties in the Israeli Knesset.) But Rabin was unfazed. “I will make peace with whatever majority is available,” he declared.

Oslo represented more than just hope for peace. It also represented prosperity. Everyone — Israeli and Palestinian alike — hoped for a turn in their fortunes. Both the PLO and the Israeli media marketed Oslo as a harbinger of untold riches. The financial section of an Israeli newspaper featured a cartoon of a dove with a $100 bill in its mouth.

So many Israelis believed in this promise. In one of the largest rallies of the country’s history, over 100,000 Israelis gathered in Tel Aviv to show their support for peace. And from the stage, Rabin joined some of Israel’s most famous folk singers in singing a song of peace.

But the cheering turned to horror soon after Rabin stepped off the stage. A young, radical law student named Yigal Amir pulled out a 9-mm Beretta and fired two shots at his country’s Prime Minister. One to the head. One to the abdomen. Less than two hours later, Rabin was dead.

The country reeled. And though I was just a kid at the time, living in Baltimore, I remember the feeling in the air, tense and charged. And I don’t think I’ll ever stop wondering what could have been.

What if Arafat had stopped the terror attacks? What if Yigal Amir had never fired those two shots? Would there really be peace in the region today?

It’s a painful and compelling question. Because as Israeli society reeled, Palestinian terror groups stepped up the attacks. By 1996, the Israeli public had had enough. In a surprise upset, they elected Benjamin Netanyahu, who had protested against Oslo from the beginning.

The peace process continued to limp along. New deals. New promises. New disappointments. By the year 2000, the relentless violence of the Second Intifada had eroded any real hope for peace.

So in the end, did the Oslo Accords accomplish anything? Well, they got Israelis and Palestinians in the same room. And they also disappointed them equally. Ami Ayalon, the former head of the Shin Bet, Israel’s internal security service, reflected: “Both sides felt cheated…We didn’t get security, and they didn’t get a state.”

Remember, Oslo didn’t even promise a two-state solution. It only mandated that the West Bank would be split into different regions, with different laws for each. That the Palestinians would have a democratic and autonomous government.

But even that seems out of reach today. Gaza is governed by Hamas, a terrorist group with little interest in democracy. The Palestinian Authority in the West Bank has not held an election in nearly two decades. It’s hard not to feel empathy for the Palestinian people, hanging in limbo between terrorists on one side, and widespread political corruption on the other.

For Israelis, Oslo exposed the fault lines in a divided society. As the security situation deteriorated, the Israeli public moved farther to the right, convinced that peace with the Palestinians was little more than a mirage. A beautiful picture with little substance behind it.

But maybe there is hope. In 2021, Israel established diplomatic relations with the UAE, Morocco, Sudan, and Bahrain. Yes: Arab countries who had once refused to recognize the Jewish state are now signing normalization statements named — fittingly — after the father of Judaism and Islam. These Abraham Accords show us that peace can exist between the unlikeliest of people. So, while I think we need to learn from the lessons of Oslo, we shouldn’t let cynicism cloud our hope for an eventual peace between Israelis and Palestinians.

Shimon Peres said it best. Optimists and pessimists die the same death but live very different lives. Let’s continue working to make peace possible.