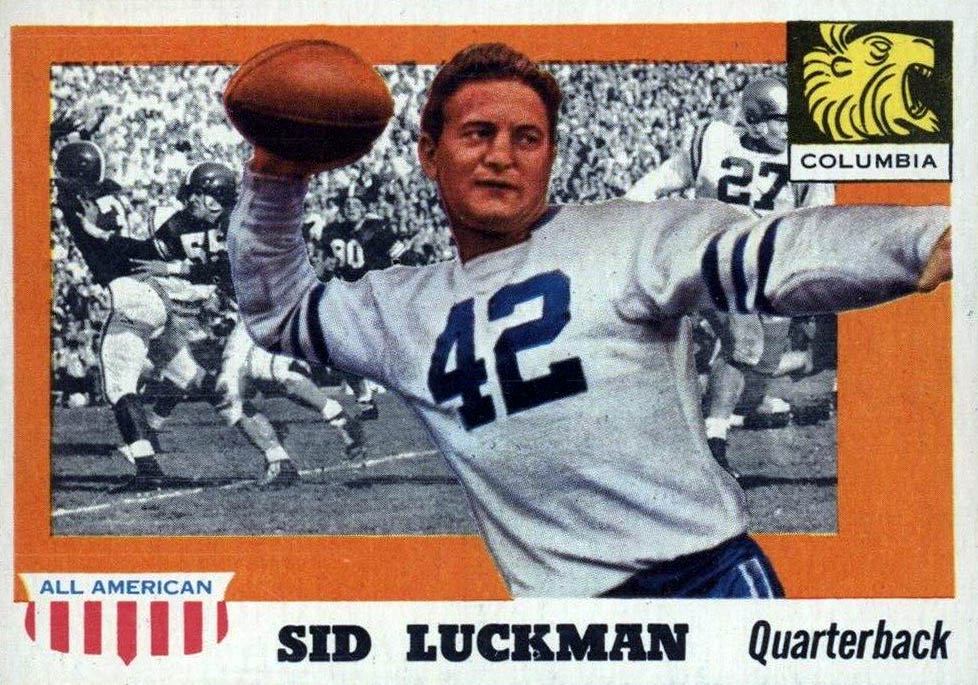

Before Patrick Mahomes, before Tom Brady, before Joe Montana, before Johnny Unitas, and even before the Super Bowl, there was Jewish quarterback Sid Luckman.

It seems far-fetched today, but the Chicago Bears were the NFL’s pacemaker between 1932 and 1946. In those 16 years, the franchise won six league titles, reached three more NFL Championship Games, and the “Monsters of the Midway” moniker struck fear in opposition hearts.

The eye of the dynasty came in the early 1940s when the Bears played in the NFL Championship Game four consecutive years from 1940 through 1943, bringing the crown back to Chicago in 1940, 1941, and 1943. In 1946, they gave Chicago an encore with another triumph.

None of this would have happened without Luckman.

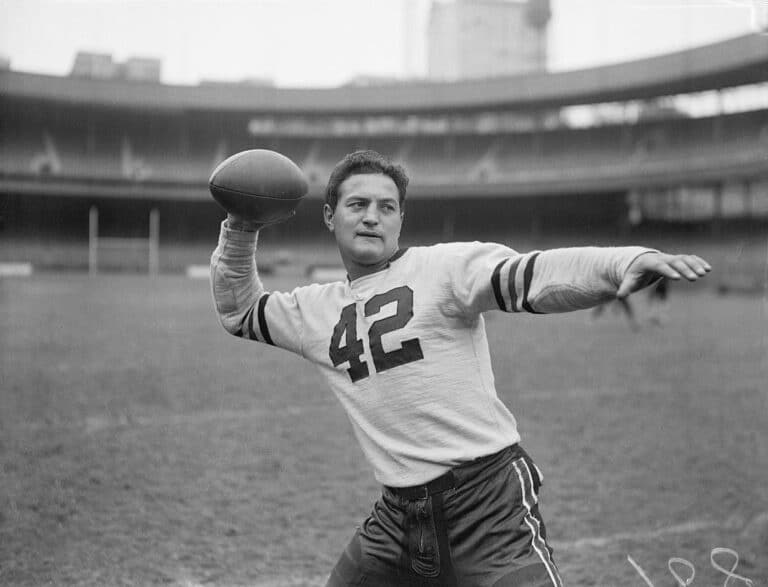

The Jewish quarterback served as a gunslinger for the Bears from 1939 to 1950. In those 12 seasons, he played in three Pro Bowls (1940-42), was named an All-Pro five times (first team in 1941-44 and 1947, second team in 1946), and he added the Carr Trophy – the first version of the league’s MVP award – to his cabinet in 1943.

By the time Luckman retired from the NFL, he had thrown the second-most career passing yards (14,686) and career touchdowns (137) in league history. His 7.9 percent passing touchdown rate remains the greatest the NFL has ever seen.

Yet, most people know little of Luckman and his accomplishments, let alone his life. But the truth is: One of the best quarterbacks ever was a Jew with a crazy story.

Football Love

Sidney Luckman was born on Nov. 21, 1916, in Brooklyn, New York, to Meyer and Ethel Luckman, two German-Jewish immigrants. It was there that Sid began passing the pigskin.

Even though his father knew little of the game, Meyer introduced his son to the gridiron. He took Sid to his first NFL game in 1929, affording him the opportunity to witness Benny Friedman play quarterback in the flesh for the New York Giants. A fellow Jew, Friedman inspired Sid spiritually and literally – Friedman showed the NFL how to pass, footsteps which Sid later followed, and showed the little Jewish kid from Brooklyn that he could do it, too.

By age 8 when Meyer gifted Sid his first football, he had become a devoted athlete. Sid later adopted baseball and became a superstar two-sport athlete at Erasmus High School, but his football ability and passion always took center stage. Colleges came calling for his commitment. Sid’s stock was through the roof. He was heralded as the next big thing by those paying enough attention.

Sid chose Columbia University, despite the university offering no athletic scholarships. The team was losing steam in national prestige, viewed as a program of yesteryear by the mid-1930s. But attending Columbia allowed Sid to stay close to home. It also brought him under the wing of the team’s head coach, Lou Little.

Family Troubles

In the background, Meyer printed money via his family trucking company, Luckman Brothers Trucking. This was in part due to his business acumen. It was also thanks to his connections to Murder Inc., the Jewish mafia that held serious sway in Brooklyn in the 1930s and 1940s. This supplied a comfortable life for the family for much of Sid’s young life, but it came crashing down in 1935.

Meyer was arrested for murdering his brother-in-law, Samuel Drukman, who drove for the family trucking outfit. Gambling losses sunk Drukman into a deep hole and, rather than asking for help, he chose to skim off the top of delivery payments.

Police found Drukman dead in a Luckman Brothers garage with his killers at the scene. They were arrested but quickly released. Some money changed hands. Months later, news of a $100,000 bribe (worth over $2 million in 2024) to shut down the murder investigation hit the news. The scandal became a frenzy in New York, and it culminated in a culling within the NYPD, a detective’s suicide, and Meyer’s conviction on second-degree murder charges. He was sentenced to spend 20 years in Sing Sing Prison.

Read more: How did Jewish pro baseball player Moe Berg become a CIA spy?

Meyer’s trial was major news. It devoured front pages. Sid was often in attendance with his family in the courtroom, but the media never linked the father and son. When reporting on all the touchdowns Sid was throwing at Columbia, his father’s criminal history was not mentioned. When covering the murder and fallout, Meyer’s son was not included.

“This was a hands-off time,” R.D. Rosen, author of “Tough Luck: Sid Luckman, Murder, Inc., and the Rise of the Modern NFL,” said in 2019. “It was a very courteous media that observed the fine line between an athlete’s public and private lives. If I were to speculate, I would say that the thinking was, ‘We love this guy, let’s not saddle him in print with the misdeeds of the father.’”

This allowed Sid to flourish on the field without the wider public connecting the dots. That protection continued during Sid’s time in Chicago as a Bear.

The NFL Decision

Luckman’s life off the field didn’t detract from his life on it. Right as he was on his way out of high school and into college, his father became wrapped in his legal troubles. Though the media didn’t associate Meyer and Sid in print, the young quarterback’s peers knew, and he had to handle the stigma.

Like most freshman in the Ivy League program, Luckman didn’t play football, focusing on his schoolwork at Columbia’s undergrad program to train the next generation of teachers: the New College for the Education of Teachers. It wasn’t until his sophomore year that he stepped onto the field for Little’s Lions.

Read more: Everything to know about Jewish baseball hero Sandy Koufax

Luckman made an instant impact that season and was an important figure for Columbia. His career stats of 2,413 passing yards, 20 touchdown passes, and 180 pass completions on 376 attempts doesn’t sound great to the modern football fan, but those were some serious numbers in the 1930s. Luckman was an All-American in 1937 and 1938 and placed third in the 1938 Heisman Trophy race.

It wasn’t until his NFL days that Luckman was allowed to truly chuck the ball downfield, but that almost didn’t happen. After college, Luckman initially didn’t want to continue with football. He wanted to stay home and in his family’s trucking business. That wasn’t acceptable to George Halas, though.

The Bears owner and head coach had seen Luckman play against Syracuse University in his senior year. It convinced Halas that his team needed this Jewish kid from Brooklyn. In pursuit of Luckman, he shipped a couple players east to Pittsburgh for the No. 2 pick in the 1939 NFL Draft.

Luckman declined to sign. Halas wouldn’t hear it. He flew to New York to change Luckman’s mind. A contract worth $6,000 was enough to do it. To seal the deal, Halas kissed Luckman’s new wife, Estelle, on her cheek and made a toast to Luckman.

“You and Jesus Christ are the only two people I’d ever pay that much money to,” Halas said.

With that, Luckman made his way west, and football was forever altered.

Revolutionizing the League

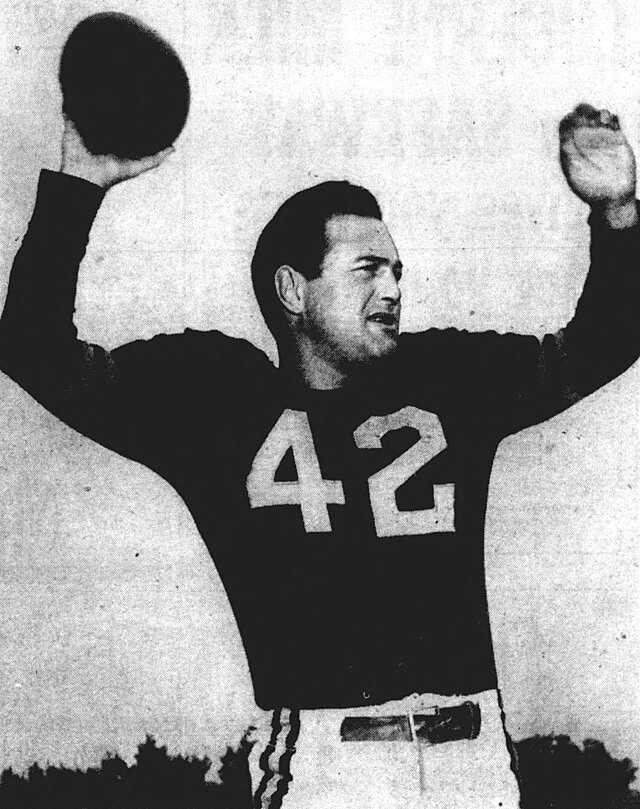

In some ways, Luckman was the first pocket passer – he was the league’s first QB to throw for more than 2,000 yards in a season, throw 25 touchdown passes in a season, and the seven touchdowns he threw against the New York Giants on Nov. 14, 1943 still stands as the most touchdown tosses in a single outing. The forward pass was just becoming cool, and Luckman was its poster child.

It took Luckman a season to adjust to the big leagues. He was working to nail down the updated version of T-formation offense, and it took time to do so. He was so committed to the cause that Halas had to make him sleep.

“Ralph Jones had coached the T with the Bears in the early 1930s, but it was the old T, with everyone bunched in there,” Luckman told Sports Illustrated in 1998. “(Clark) Shaughnessy was coaching at the University of Chicago, and they were about to drop football, so he spent a lot of time with us. I’d be up in Shaughnessy’s room every night in training camp, going over every aspect of the thing. The whole idea was to spread the field and give the defense more area to cover. We had an 11 o’clock curfew, and Halas would drop by around 1 a.m. and say, ‘That’s enough, Sid. Go to bed.’”

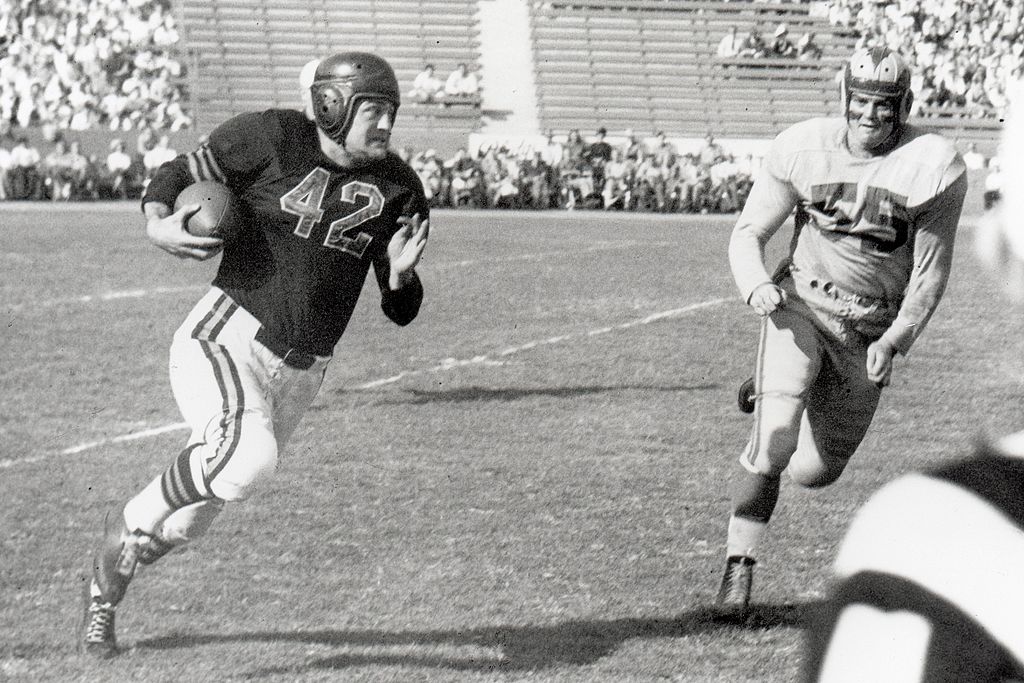

By his second year, Luckman was running the modern T formation with a man in motion, a revolution in the game of football. He led the Bears to the 1940 championship in rousing fashion, trouncing the Washington Redskins, 73-0, in the campaign’s ultimate contest. Though Luckman only attempted six passes, he completed four for 102 yards and a touchdown. The rest of the league was officially on notice, and the innovations unfolding in the Windy City helped popularize the NFL.

Read more: Hank Greenberg’s legacy of breaking barriers and inspiring pride

The legend only grew. The quarterback improved in 1941, completing a career-best 57.1 percent of his pass attempts, and had his Bears back in the final again. Chicago routed the Giants, 37-9, completing a near-perfect season with a back-to-back NFL title and 12-1 record, including the playoffs.

December 15, 1946 — Chicago Bears beat the New York Giants 24-14 at the Polo Grounds for the NFL championship. A record crowd of 58,326 attend the game. Sid Luckman’s 19-yard touchdown run in the fourth puts the Bears ahead 21-14. Credit AP. pic.twitter.com/X7NYGPjALo

— PFRA (@FootballHistory) December 15, 2020

The Bears posted an undefeated 11-0 going into the 1942 NFL Championship Game. The Redskins exacted revenge for the annihilation two years earlier, 14-6, denying Luckman’s team a three-peat. The Monsters of the Midway paid Washington back in 1943 with a 41-21 triumph in that year’s title bout; Luckman made up for a lackluster showing in 1942 with 286 passing yards, five passing touchdowns, a 57.7 completion percentage, and 64 rushing yards to boot. It was the exclamation point on the best season of the player’s career, which came as he served locally as a member of the U.S. Merchant Marines during World War II.

Luckman and the team lost steam the next couple of seasons, but they were right back in the mix in 1946. Chicago didn’t dominate as it had during some past title runs. But it handled business at the right time. Luckman threw two interceptions and completed less than 41 percent of his passes, but he hit paydirt for the game-winning touchdown in the fourth quarter as the Bears overcame the Giants, 24-14.

That was the last time Luckman’s Bears played in the NFL Championship Game, and he was no longer the starter for Chicago by 1949. He remained with the team until retiring from pro football after the 1950 season.

Life After Retirement

Luckman accepted the Bears’ vice president role in 1951, keeping himself involved with the franchise and sport while he also worked on the various businesses he had invested in during the last half of his playing career. He became Chicago’s quarterbacks coach in 1954 and remained in that role well into the 1960s. Luckman also helped Notre Dame, Holy Cross, University of Pittsburgh, and Army perfect the T-formation.

The quarterback entered the College Football Hall of Fame in 1960, then the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1965. Luckman remained close to Halas and his family, Little, and many others who impacted him throughout his football career and life.

Luckman moved to Aventura, Florida, in the early 1980s, where he spent the final 17 years of his life. He died on July 5, 1998, at Aventura Hospital and Medical Center. He was 81 years old. His three children and many grandchildren and great-grandchildren are his legacy.

The football pioneer is buried in Skokie, Illinois. His gravestone relays a simple yet powerful message.

“I had it all. I did it all. I loved it all.”