Here’s a rundown of everything you need to know about Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, and how to celebrate it.

Read more: Get our guides to all the Jewish holidays.

What is Rosh Hashanah (quick version)?

Rosh Hashanah means “Head of the Year” and is the Jewish new year. It is a day of celebration as well as reflection about the previous year and changes we want to make in the year ahead.

Rosh Hashanah has multiple names that invoke different components of the day:

- Yom Hadin (The Day of Judgment) — This is a time when we each stand before God as the Ultimate Judge and are called to judge our own actions as well.

- Yom Hazikaron (The Day of Remembrance) — We pray that God will “remember” us by inscribing us in the Book of Life, and we “remember” our own deeds over the past year.

- Yom Harat Olam (The Day the World Was Conceived) — Rosh Hashanah is associated with creation based on a tradition that the world was created in the month of Tishrei.

- Yom Teruah (The Day of Blasting) — The shofar is sounded at Rosh Hashanah services as a call to repentance.

When is Rosh Hashanah 2024?

Rosh Hashanah is celebrated on the first and second days of the Hebrew month of Tishrei. It begins the evening of Wednesday, October 2, 2024, through the evening of Friday, October 4, 2024.

How to wish someone a happy new year

There are several different ways to wish someone a happy new year or greet someone on Rosh Hashanah. You can simply say “Happy new year” or use one of the following:

- Shana tova (Have a good year)

- L’shana tova (For a good year)

- Shana tovah u’metukah (Have a good and sweet year)

- Chag sameach (Happy holiday)

- Gmar chatima tova (A good signing/sealing) — This is said between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur and references the belief that our fates are “written” on Rosh Hashanah and “sealed” on Yom Kippur. It expresses the wish that someone will be inscribed in the Book of Life.

- Ketiva v’chatima tova (A good writing and sealing)

In addition to the greetings above, Sephardim greet each other with the Ladino expression Anyada Buena, Dulse i Alegre (“May you have a good, sweet and happy New Year”) or the Hebrew greeting, Tizku leshanim rabot (“May you merit many years”), to which one answers, Tizkeh vetihyeh ve-ta’arich yamim (“May you merit and live and increase your days”).

Rosh Hashanah basics:

If you’re attending a Rosh Hashanah celebration, here are a few things you can expect.

- Apples and honey: Jews traditionally dip apples in honey on Rosh Hashanah to express the wish for a sweet new year.

- New fruit: It is customary to eat a new, seasonal fruit that hasn’t been tasted since the previous year to symbolize the new year.

- Round challah: Instead of a braided challah, a round challah is served on Rosh Hashanah, symbolizing the circular nature of the year.

- Brisket, chicken, tzimmes, kugel: These traditional Jewish foods are frequently served at Rosh Hashanah meals in Ashkenazi Jewish homes.

- Chicken, lamb, dried fruits, rice, couscous, sweet potato, pumpkin or leek patties: These foods are frequently on the Rosh Hashanah menu in Sephardic Jewish homes.

What is Rosh Hashanah all about?

Rosh Hashanah is both a joyful and serious occasion. It is associated with creation based on a tradition from the Talmud (Rosh Hashanah 10b) that the world was created in the month of Tishrei. Because of this, one of the many names of Rosh Hashanah is “yom harat olam” (the birthday of the world).

At the same time, Rosh Hashanah is a day of accounting and judgment. The High Holiday liturgy states, “On Rosh Hashanah it is written, on Yom Kippur it is sealed…” This refers to the belief that on Rosh Hashanah, the Book of Life is opened, and on Yom Kippur, our fates are sealed for the coming year (we hope we will be inscribed in the Book of Life). This is a time when we each stand before God as the Ultimate Judge and when we are called to judge our own actions as well. That is why another name for Rosh Hashanah is “Yom Hadin,” the day of judgment.

The theme of accounting and judgment begins in the month of Elul (leading up to Rosh Hashanah) when Jews engage in cheshbon hanefesh (“an accounting of the soul”). This entire month is a “preparatory period” of introspection and reflection about our mistakes in the past year and how we can improve our behavior in the coming year. There are a number of special observances in the month of Elul. The shofar is sounded immediately following morning services as a call to repentance, and Psalm 27 and selichot (prayers of repentance) are recited. Sephardic Jews begin reciting selichot on the second day of the Hebrew month of Elul, while Ashkenazi Jews start reciting them on the Saturday night before Rosh Hashanah.

What is teshuvah?

One of the central themes of Rosh Hashanah and the High Holiday season is teshuvah (meaning “repentance” or “return”). This describes the process in which we acknowledge what we have done wrong, feel regret and vow not to do it again. Jewish tradition says that through teshuvah, we can influence our own fate and have an opportunity to be inscribed in the Book of Life. The Unetaneh Tokef prayer states this idea: “But repentance, prayer and righteousness avert the severity of the decree.”

In his Mishneh Torah (his magnum opus and code of Jewish law), Hilchot Teshuvah (Laws of Repentance) 2:1, Rambam (Maimonides) describes what it looks like when teshuvah has truly occurred: “What is complete teshuvah? When a person has the opportunity to commit the same sin, but he separates himself from it and does not do it.” Rambam lays out a multistep process of teshuvah, and all of the steps are necessary:

- Acknowledgement that one has done something wrong.

- Public confession of one’s wrongdoing to both God and the community.

- Public expression of remorse.

- Resolve by the offender not to sin in this way again (perhaps announced publicly).

- Compensation of the victim for the injury inflicted, accompanied by acts of charity to others.

- Sincere request of forgiveness by the victim — with the help of the victim’s friends and up to three times, if necessary (and even more if the victim is one’s teacher).

- Avoidance of the conditions that caused the offense, perhaps even to the point of moving to a new locale.

- Acting differently when confronted with the same situation in which the offender sinned the first time. (Source: Rabbi Elliot Dorff, Love Your Neighbor And Yourself: A Jewish Approach to Modern Personal Ethics)

The great modern Jewish thinkers Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook (more commonly known as Rav Kook) and Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik expanded on the idea of teshuvah.

According to Rabbi Elkayim Krumbein, an educator at Yeshivat Har Etzion in Israel, “While the early sources give the impression that the crux of teshuva is the correction of sin, Rav Soloveitchik zt’l and Rav Kook zt’l both taught that its purpose is the correction of man. Of course, man’s deviation and corruption are expressed in his sins, but [in both Rav Kook and Rabbi Soloveitchik’s thinking] the real source of the problem is man’s distance from his Creator.”

As you can see from their ideas below, while Rav Kook describes teshuva as a process of returning to oneself, Rabbi Soloveitchik envisions it as a process of recreating oneself.

- Rav Kook: “The primary role of Teshuva is for the person to return to himself, to the root of his soul. Then he will at once return to himself, to the Soul of all souls. This is true whether we consider the individual, a whole people or the whole of humanity…which always becomes damaged when it forgets itself.

- Rabbi Soloveitchik: “A person is creative; he was endowed with the power to create at his very inception. When he finds himself in a situation of sin, he takes advantage of his creative capacity, returns to God and becomes a creator and self-fashioner. Man, through Teshuva, creates himself, his own ‘I’…”

There are two major types of transgressions in Judaism: transgressions against God and transgressions against other people. One of the main principles of teshuvah and atonement is stated in the Mishnah: “For transgressions between a person and God, Yom Kippur atones; however, for transgressions between a person and another, Yom Kippur does not atone until he appeases the other person.” In other words, to atone for sins against other people, forgiveness must be received and any restitution owed to the victim must be paid.

Other things to know:

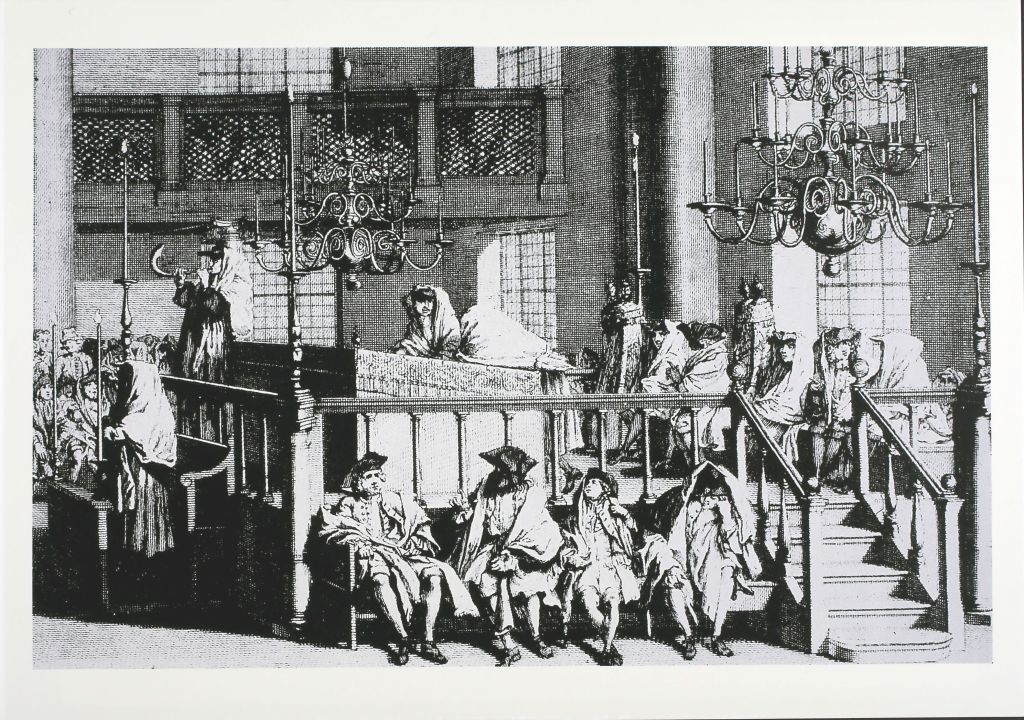

Shofar

A shofar is a ram’s horn that is blown at Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur services as well as every morning of Elul. The four sounds of the shofar are tekiah, shevarim, teruah and tekiah gedolah.

Rambam (Maimonides) wrote that although it is a commandment to hear the shofar on Rosh Hashanah, the shofar seems to say, “Awake, awake, O sleepers from your sleep; O slumberers, arouse thee from your slumbers; and examine your deeds, return in repentance and remember your Creator… Abandon, every one of you, his evil course and thought that is not good.”

Saadiah Gaon, another medieval Jewish philosopher who was born about 200 years before Rambam, listed 10 reasons for blowing the shofar. Below are a few of them:

- “The shofar is sounded to stir our consciences, inducing us to confront our past errors and return to God, who is always ready to welcome the penitent.”

- “The shofar, since it is a ram’s horn, is reminiscent of the ram offered as a sacrifice by Abraham in place of his son Isaac.” (The story of the Binding of Isaac is read on the second day of Rosh Hashanah.)

- “The shofar urges us to feel humble before God’s majesty and might, which are manifested by all things and which constantly surround our lives.”

Mahzor

The prayer book that is used at Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur services is called a mahzor (a siddur is used the rest of the year). In contrast to the siddur, the mahzor includes lots of liturgical poetry (piyyutim), the prayer “Avinu Malkeinu” (“Our Father, Our King”) and the shofar. It also has Rosh Hashanah prayers about three main themes: Malkhuyot (Kingship), Zichronot (Remembrances), and Shofarot (Blasts of the Shofar).

Tashlich

Tashlich is a ceremony in which Jews throw pieces of bread into a body of water to symbolize casting away their sins. Verses from the Book of Micah are recited, such as, “He will take us back in love; He will cover up our iniquities, You will cast (tashlich) all our sins into the depths of the sea” (7:19). Although Tashlich is typically done on the afternoon of the first day of Rosh Hashanah, it can be performed until the end of Sukkot.

The 10 Days of Repentance

The Aseret Yemei Teshuvah (or 10 Days of Repentance) refers to the period between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. According to Rambam (Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Teshuvah, Laws of Repentance, 2:6), “Although repentance and prayer are always effective, they are even more effective during the Aseret Yemei Teshuvah when they are accepted immediately.” Jews often ask forgiveness of people they may have wronged during the year in these 10 days. This is a time of contemplation and self-examination leading up to Yom Kippur.

Rosh Hashanah services:

Torah readings:

- Day 1: Bereshit (Genesis) 21:1-34: The birth of Isaac, exile of Hagar and Ishmael

- Day 2: Bereshit (Genesis) 22: 1-24: The Akeidah (binding of Isaac)

Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur Prayers:

Below are excerpts from two of the most important and stirring prayers of the High Holidays.

Unetaneh Tokef (“We shall ascribe holiness to this day”)

We shall ascribe holiness to this day.

For it is awesome and terrible.

Your kingship is exalted upon it.

Your throne is established in mercy.

You are enthroned upon it in truth.

In truth You are the judge,

The exhorter, the all‑knowing, the witness,

He who inscribes and seals,

Remembering all that is forgotten.

You open the book of remembrance

Which proclaims itself,

And the seal of each person is there.

The great shofar is sounded,

A still small voice is heard.

The angels are dismayed,

They are seized by fear and trembling

As they proclaim: Behold the Day of Judgment!…

On Rosh Hashanah it is inscribed,

And on Yom Kippur it is sealed.

How many shall pass away and how many shall be born,

Who shall live and who shall die,

Who shall reach the end of his days and who shall not,

Who shall perish by water and who by fire,

Who by sword and who by wild beast…

Avinu Malkeinu (“Our Father, Our King”)

Our Father, our King!

we have sinned before You.

Our Father our King!

we have no King except You.

Our Father, our King!

deal with us [kindly]

for the sake of Your Name.

Our Father, our King!

renew for us a good year…

Our Father, our King!

hear our voice,

spare us and have compassion upon us.

Our Father, our King!

accept our prayer with compassion and favor.

Our Father, our King!

open the gates of heaven to our prayer.

Our Father, our King!

remember, that we are dust.

Our Father, our King!

please do not turn us away

empty-handed from You.

Our Father, our King!

let this hour be

an hour of compassion

and a time of favor before You.

Our Father, our King!

have compassion upon us…

Our Father, our King!

favor us and answer us

for we have no accomplishments;

deal with us charitably and kindly

and deliver us.

Originally Published Sep 30, 2024 02:27PM EDT