Yom Kippur means “Day of Atonement.” It is the holiest and most solemn day of the Jewish year and is a fast day. According to tradition, at the end of Yom Kippur, God “seals” our fates for the coming year (i.e., whether we will be inscribed in the Book of Life). The main themes of this day are sin, repentance (teshuvah) and atonement.

Read more: Get our guides to all the Jewish holidays.

Although Yom Kippur is a solemn occasion, it is also a day of joy. Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik taught that “there is also great joy on the day that our sins are forgiven” (The Rav, by Aaron Rakeffet-Rothkoff, Volume 2, p.176). Rabbi Soloveitchik noted that the community recites the Al Chet prayer (confession of sins) “with a sense of confidence and even rejoicing” (On Repentance, Pinchas Peli, p. 119).

Yom Kippur is mentioned in the Torah as “Yom Hakippurim” in Vayikra (Leviticus) 23: 27-28: “Mark, the tenth day of this seventh month is the Day of Atonement (Yom Hakippurim). It shall be a sacred occasion for you: you shall practice self-denial…you shall do no work throughout that day.”

When is Yom Kippur 2024?

Yom Kippur is observed on the 10th day of the Hebrew month of Tishrei. It begins the evening of Friday, Oct. 11, 2024, until the evening of Saturday, Oct. 12, 2024.

How is Yom Kippur traditionally observed?

Rabbi Isaac Klein, author of “A Guide to Jewish Religious Practice,” wrote, “In an effort to bring man directly before his Maker, [Yom Kippur] is observed in a manner that will remove the worshipper from every aspect of the mundane world.” Jews observe Yom Kippur by fasting, attending synagogue, praying, refraining from work and pleasurable activities, reflecting on the past year and contemplating the future.

The day before Yom Kippur, the last meal (aka. the se’udah hamafseket) must be eaten before sundown. Candles are also lit with the blessing “l’hadlik ner shel yom hakipurim.” Additionally, if one’s parent or parents are deceased, a special memorial candle (called a ner neshama) is lit in their memory and burns for the entire holiday.

Work is prohibited on Yom Kippur just like it is on Shabbat, plus there are additional prohibitions. These include eating, drinking, washing and bathing (except for hygienic purposes), sexual relations, and wearing leather (which was considered luxury apparel in earlier times). It is traditional to dress in white on Yom Kippur, symbolizing purity and the opportunity to begin the new year with a clean slate. To avoid leather footwear, many wear canvas sneakers, flip flops, Crocs or wedge sandals.

How to greet someone on Yom Kippur

There are several ways to greet someone on Yom Kippur, and leading up to the day. Because of the solemn nature of the day, it is not traditional to wish someone a “Happy Yom Kippur.” You can use any of these options:

- Gmar chatima tova (A good final sealing) — This is said in between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, and in the early hours of the fast on Yom Kippur. It is based on the belief that our fates are “written” on Rosh Hashanah and “sealed” on Yom Kippur. This expresses the wish that someone will be inscribed in the Book of Life.

- Gmar tov — This is a shortened version of Gmar chatima tova.

- Ketiva v’chatima tova (A good writing and sealing)

- Tzom kal (Have an easy fast)

- Chag sameach (Happy holiday)

- Have an [easy / meaningful / easy and meaningful] fast

- Have a meaningful Yom Kippur

Yom Kippur: The culmination of a process

Yom Kippur is the culmination of a period that begins on the first of Elul (the preceding month). During the month of Elul, Jews engage in cheshbon hanefesh (“an accounting of the soul”), meaning reflection and self-examination. This prepares us for Rosh Hashanah, when it is believed that God “opens” the Book of Life and writes our fates for the coming year.

The 10 Days of Repentance between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur is a period of further self-examination and contemplation. During these 10 days, Jews often ask forgiveness of people they may have wronged during the year and engage in teshuvah (meaning “repentance” or “return”). This describes the process in which we acknowledge what we have done wrong, feel regret and vow not to do it again.

Jewish tradition says that through teshuvah, we can influence our own fate and have an opportunity to be inscribed in the Book of Life. The Unetaneh Tokef prayer states this idea: “U-teshuvah u-tefilah u-tzedakah ma’avirin et roa hagezeira” (“But repentance, prayer and righteousness avert the severity of the decree”).

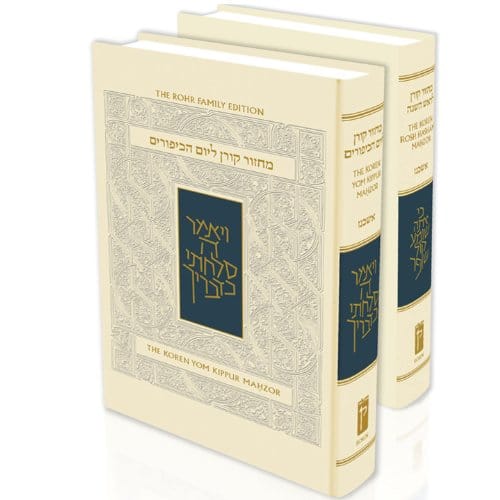

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks elaborated on this in the footnotes of the Koren Mahzor (High Holiday prayer book): “Repentance is our relationship to ourselves. Prayer is our relationship to God. Tzedakah, charity is our relationship to others. We should be honest in our relationship with ourselves, humble in our relationship to God and generous in our relationship to others.”

Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson (commonly known as the Lubavitcher Rebbe) explained the three terms as follows:

- Teshuvah means “return.” It tells us that every sin is a form of being lost; we are not where we are meant to be. Teshuvah means coming home.

- Tefilah comes from the verb meaning “to judge.” Lehitpalel means “to judge oneself.” In tefilah we are both subject and object, the doer and the judge of what we do. It is this capacity for self-judgment that makes us capable of moral growth.

- Tzedakah means justice, or justice and charity combined. There is no word for this in English. In Judaism we give, not out of charity but out of justice.

The 10 Days of Repentance prepares us for Yom Kippur, at the end of which our fates are “sealed.” Yom Kippur is the time when each person stands before God as the Ultimate Judge, and when we are called to judge our own actions and repent for sins we committed in the past year.

The Yom Kippur service

The Yom Kippur liturgy reflects the process described above, taking worshippers through a journey of repentance and prayer leading up to the “final sealing” of the Book of Life:

- Shaharit (daily morning service)

- Selichot (prayers of repentance)

- Viddui (communal confession of sins)

- Torah and Haftarah readings

- Yizkor (memorial service)

- Musaf (additional service for Yom Kippur)

- Avodah (describes the sacrificial ritual that was performed in Temple times)

- Mincha (afternoon service)

- Neilah (concluding service reflecting the idea that “the gates of Heaven are closing” and this is our final opportunity for repentance and prayer before God “seals” our fates)

- Shofar (a long blast of tekiah gedolah signifies the end of Yom Kippur)

- Maariv (evening service)

- Break fast

What is teshuvah?

In his Mishneh Torah (Rambam’s magnum opus and code of Jewish law), Hilchot Teshuvah (Laws of Repentance) 2:1, Rambam (Maimonides) describes what it looks like when teshuvah has truly occurred: “What is complete teshuvah? When a person has the opportunity to commit the same sin, but he separates himself from it and does not do it.”

The great modern Jewish thinkers Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook (more commonly known as Rav Kook) and Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik expanded on the idea of teshuvah.

According to Rabbi Elkayim Krumbein, an educator at Yeshivat Har Etzion in Israel, “While the early sources give the impression that the crux of teshuva is the correction of sin, Rav Soloveitchik zt’l and Rav Kook zt’l both taught that its purpose is the correction of man. Of course, man’s deviation and corruption are expressed in his sins, but [in both Rav Kook and Rabbi Soloveitchik’s thinking] the real source of the problem is man’s distance from his Creator.”

As you can see from their ideas below, while Rav Kook describes teshuva as a process of returning to oneself, Rabbi Soloveitchik envisions it as a process of recreating oneself.

- Rav Kook: “The primary role of Teshuva is for the person to return to himself, to the root of his soul. Then he will at once return to himself, to the Soul of all souls. This is true whether we consider the individual, a whole people or the whole of humanity…which always becomes damaged when it forgets itself.

- Rabbi Soloveitchik: “A person is creative; he was endowed with the power to create at his very inception. When he finds himself in a situation of sin, he takes advantage of his creative capacity, returns to God and becomes a creator and self-fashioner. Man, through Teshuva, creates himself, his own ‘I’…”

There are two major types of transgressions in Judaism: transgressions against God and transgressions against other people. One of the main principles of teshuvah and atonement is stated in the Mishnah (Yoma 8:9): “For transgressions between a person and God, Yom Kippur atones; however, for transgressions between a person and another, Yom Kippur does not atone until he appeases the other person.” In other words, to atone for sins against other people, forgiveness must be received and any restitution owed to the victim must be paid.

What is Kol Nidrei?

Kol Nidrei (pronounced “Kohl Nih-dray”) means “all vows” and is a prayer set to a beautiful melody that is recited immediately prior to sunset on the evening of Yom Kippur. In the prayer, the congregation proclaims that all vows that were made under duress during the year should be considered null and void.

Rabbi Daniel Kohn explained the origin of Kol Nidre: “This legal ritual is believed to have developed in early medieval times as a result of persecutions against the Jews. At various times in Jewish history, Jews were forced to convert to either Christianity or Islam upon pain of death. After the danger had passed, many of these forced converts wanted to return to the Jewish community. However, this was complicated by the fact that they had been forced to swear vows of fealty to another religion. Because of the seriousness with which the Jewish tradition views verbal promises, the Kol Nidrei legal formula was developed to enable those forced converts to return and pray with the Jewish community, absolving them of the vows that they made under duress.”

It is important to note that Kol Nidrei does not provide release from vows and promises made to other people. One can only be absolved of these broken promises if forgiveness has been granted from the other party. As the Mishnah Yoma 8:9 (mentioned earlier) states, “For transgressions between a person and another, Yom Kippur does not atone until he appeases the other person.”

Other things to know

Mahzor

The prayer book that is used at Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur services is called a mahzor (a siddur is used the rest of the year). Unlike the siddur, the mahzor includes lots of liturgical poetry (piyyutim), the prayer “Avinu Malkeinu” (“Our Father, Our King”) and the shofar.

Shofar

A shofar is a ram’s horn that is blown at Rosh Hashanah services and at the end of Yom Kippur services, as well as every morning of Elul. The four sounds of the shofar are tekiah, shevarim, teruah and tekiah gedolah. A long blast of tekiah gedolah is blown at the end of Yom Kippur to signify the end of the holiday.

Break fast

This is the meal eaten immediately after Yom Kippur to break the fast. In Ashkenazi Jewish homes, it is common to serve bagels, cream cheese, kugel, fresh fruit and coffee at this meal. In Sephardic Jewish homes, the menu might include dairy foods, soups and stews, and other dishes that would be served at a lunch or dinner as opposed to brunch.

Torah and Haftarah readings on Yom Kippur

- Torah reading in the morning service: Vayikra (Leviticus) 16: 1-34 (description of the sacrificial service on Yom Kippur) and Bamidbar (Numbers) 29: 7-11 (sacrifices offered in the Temple on Yom Kippur)

- Haftarah reading: Yeshayahu (Isaiah) 57:14 – 58:14: The prophet Isaiah tells the people that fasting is not an end in and of itself, but must be accompanied by righteousness and good deeds.

“Is such the fast I desire, A day for men to starve their bodies? Is it bowing the head like a bulrush And lying in sackcloth and ashes? Do you call that a fast, A day when the LORD is favorable? No, this is the fast I desire: To unlock fetters of wickedness, And untie the cords of the yoke To let the oppressed go free; To break off every yoke. It is to share your bread with the hungry, And to take the wretched poor into your home; When you see the naked, to clothe him, And not to ignore your own kin.” (Yeshayahu 58: 5-7)

Yom Kippur prayers

Below are excerpts from some of the most important prayers recited on Yom Kippur.

Viddui (“Confession”)

We have trespassed [against God and man, and we are devastated by our guilt];

We have betrayed [God and man, we have been ungrateful for the good done to us];

We have stolen; We have slandered.

We have caused others to sin;

We have caused others to commit sins for which they are called רְשָׁעִים, wicked;

We have sinned with malicious intent;

We have forcibly taken others’ possessions even though we paid for them;

We have added falsehood upon falsehood; We have joined with evil individuals or groups;

We have given harmful advice;

We have deceived; we have mocked;

We have rebelled against God and His Torah;

We have caused God to be angry with us;

We have turned away from God’s Torah;

We have sinned deliberately;

We have been negligent in our performance of the commandments;

We have caused our friends grief;

We have been stiff-necked, refusing to admit that our suffering is caused by our own sins.

We have committed sins for which we are called רָשָׁע, [raising a hand to hit someone].

We have committed sins which are the result of moral corruption;

We have committed sins which the Torah refers to as abominations;

We have gone astray;

We have led others astray.

Unetaneh Tokef (“We shall ascribe holiness to this day”)

We shall ascribe holiness to this day.

For it is awesome and terrible.

Your kingship is exalted upon it.

Your throne is established in mercy.

You are enthroned upon it in truth.

In truth You are the judge,

The exhorter, the all‑knowing, the witness,

He who inscribes and seals,

Remembering all that is forgotten.

You open the book of remembrance

Which proclaims itself,

And the seal of each person is there.

The great shofar is sounded,

A still small voice is heard.

The angels are dismayed,

They are seized by fear and trembling

As they proclaim: Behold the Day of Judgment!…

On Rosh Hashanah it is inscribed,

And on Yom Kippur it is sealed.

How many shall pass away and how many shall be born,

Who shall live and who shall die,

Who shall reach the end of his days and who shall not,

Who shall perish by water and who by fire,

Who by sword and who by wild beast…

Avinu Malkeinu (“Our Father, Our King”)

Our Father, our King!

we have sinned before You.

Our Father our King!

we have no King except You.

Our Father, our King!

deal with us [kindly]

for the sake of Your Name.

Our Father, our King!

renew for us a good year…

Our Father, our King!

hear our voice,

spare us and have compassion upon us.

Our Father, our King!

accept our prayer with compassion and favor.

Our Father, our King!

open the gates of heaven to our prayer.

Our Father, our King!

remember, that we are dust.

Our Father, our King!

please do not turn us away

empty-handed from You.

Our Father, our King!

let this hour be

an hour of compassion

and a time of favor before You.

Our Father, our King!

have compassion upon us…

Our Father, our King!

favor us and answer us

for we have no accomplishments;

deal with us charitably and kindly

and deliver us.

Originally Published Aug 16, 2021 10:48AM EDT