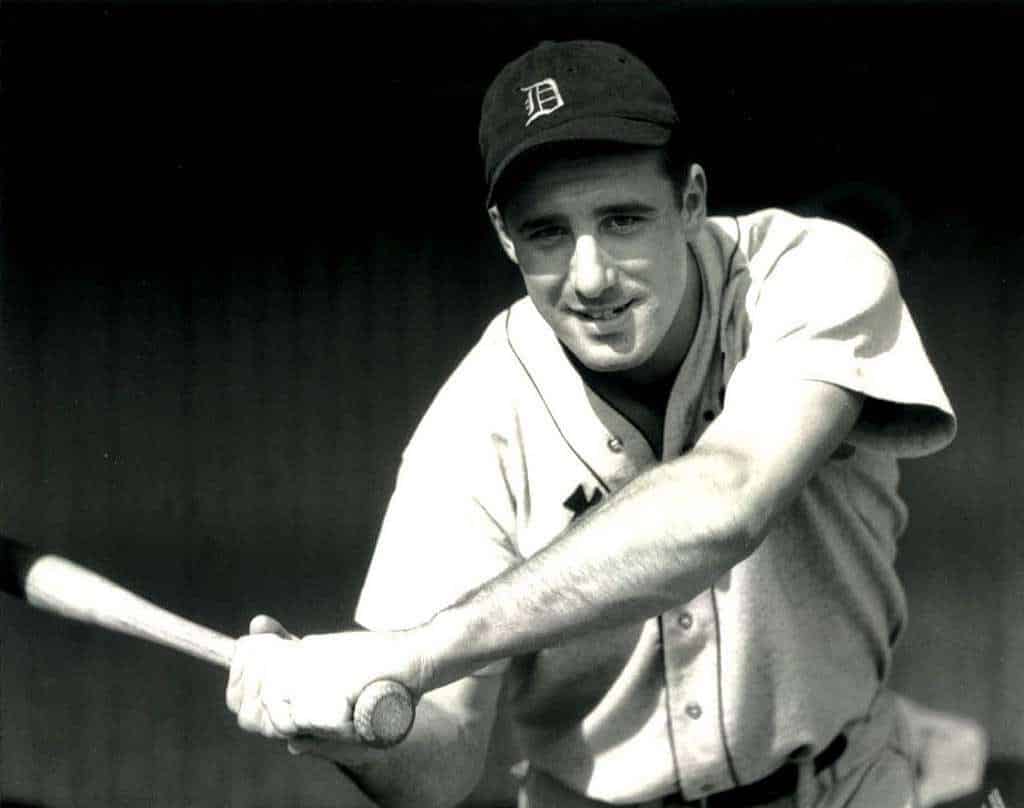

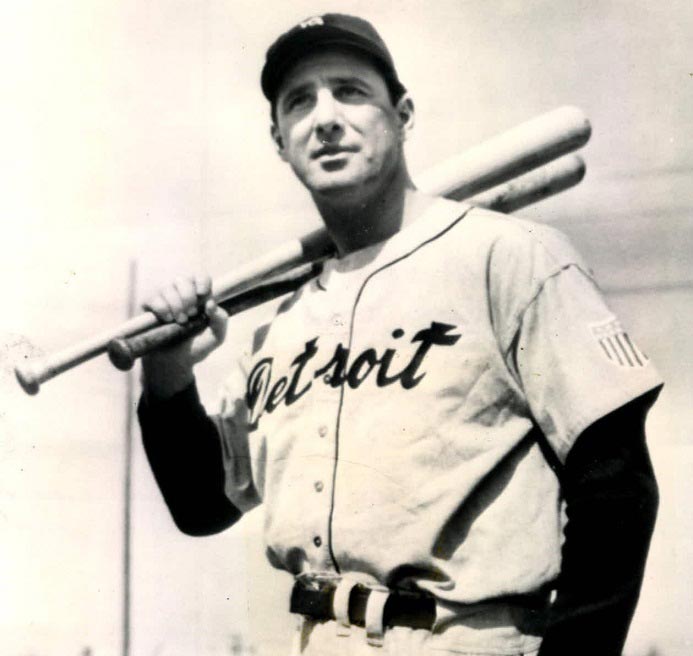

Hank Greenberg, a power-hitting first baseman for the Detroit Tigers, won two MVP awards and was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1956.

Beyond his legendary baseball career, Greenberg was also Jewish and became a symbol of Jewish pride for many Americans. Let’s unpack everything we know about Greenberg’s Jewish identity, starting with the historical backdrop of his era — World War II and rising antisemitism in the United States.

The context: America in the 1930s

The 1930s were a dark time for Jews globally. Adolph Hitler had risen to power and antisemitism was increasing in the U.S.

The pro-Nazi German American Bund, with thousands of members, operated Hitler Youth camps on American soil. Their 1939 rally in New York City’s Madison Square Garden drew 20,000 people who derided President Franklin D. Roosevelt and chanted “Heil Hitler.”

But no American city had more rabid antisemitism than Detroit — the home of Greenberg’s Tigers. Henry Ford, the automotive magnate, openly expressed his disdain for Jews, labeling them “the world’s foremost problem” in his newspaper, The Dearborn Independent.

Openly antisemitic Charles Coughlin, a Catholic priest and populist leader with a weekly radio show, reached 30 million listeners with his propaganda. He told his audience that Nazi Germany’s Kristallnacht was a reasonable response against “atheistic Jews.”

In this climate of hostility, American Jews sought a hero and a symbol of Jewish pride. They found one in Hank Greenberg, a talented Jewish athlete towering 6 foot 4 inches tall. Many Americans had never seen such a big, muscular, athletic Jew as the man who would come to be known as the “Hebrew Hammer.”

The basics

Greenberg was born on January 1, 1911, in Greenwich Village, New York City, to Jewish Romanian immigrant parents David and Sarah Greenberg. Greenberg was raised in an Orthodox household, and the family owned a cloth manufacturing business.

Greenberg attended James Monroe High School in the Bronx, a public school, where he excelled at basketball and football, but his true passion was baseball.

In September 1929, after a year at New York University, 18-year-old Greenberg signed a professional contract with the Detroit Tigers. By 1933, he had made it to the major leagues, joining the Tigers as a 6-foot-4 power hitter weighing 215 pounds.

This was the start of his exceptional career — a few highlights of which include 58 home runs in 1938, batting averages of .340, .339, and .337, over 200 hits three times, and RBI seasons of 183 and 170.

Greenberg faced antisemitism throughout his career

Greenberg endured antisemitic slurs and stereotypes throughout his professional career, starting from his time in the minor leagues. In Raleigh, North Carolina, a teammate was surprised to learn Greenberg was Jewish because he didn’t have devil horns on his head.

In the major leagues, opponents and fans heckled him unmercifully with insults like, “Throw that son of a bitch a ham sandwich.” Even a fellow Tiger teammate called him a “goddamn Jew.”

Greenberg later reflected on the antisemitic abuse he endured, saying, “Sure, there was added pressure being Jewish. How the hell could you get up to home plate every day and have [someone] call you a Jew bastard and a kike and a sheenie and [taunt you] without feeling the pressure? If the ballplayers weren’t doing it, the fans were. I used to get frustrated as hell. Sometimes I wanted to go up in the stands and beat the s— out of them.”

Acutely aware of the international climate of his time, Greenberg once remarked, “I came to feel that if I, as a Jew, hit a home run, I was hitting one against Hitler.”

Greenberg was an American patriot

As the 1930s gave way to the 1940s, the international climate worsened. Like many athletes of his time, Greenberg’s baseball career was interrupted by military service.

In May 1941, at age 30, Greenberg was drafted into the army. He served for three months before being discharged, as a new law exempted men over the age of 28 from the draft.

However, just two days after his discharge, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and the U.S. entered World War II. Feeling a strong sense of duty, Greenberg immediately re-enlisted.

“I’m going back in. We are in trouble and there is only one thing left to do — return to service. I have not been called back, I am going back of my own accord. Baseball is out the window as far as I’m concerned. I don’t know if I’ll ever return to baseball,” Greenberg declared at the time.

He served in the Pacific theater with the Army Air Corps, starting as an Infantry Sergeant and later being promoted to Second Lieutenant. At the peak of his baseball career, he spent over four years in the army before being discharged in 1945.

Greenberg’s High Holidays dilemma in 1934

In 1934, Greenberg faced a significant moral and religious dilemma that would become a defining moment in his legacy. The Detroit Tigers had games scheduled on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, forcing Greenberg to make a tough decision between his religious obligations and his team commitment.

That month, the Tigers were in first place, but the New York Yankees were right behind them, and Greenberg knew his team needed him.

But then, something remarkable happened. The day before Rosh Hashanah, The Detroit Free Press came to Hank’s defense, supporting him with a front-page headline reading in Hebrew, “L’shana Tova Tikatevu” (“May you be inscribed for a good year”).

This was an extraordinary gesture, especially considering Detroit’s reputation for antisemitism at the time. The newspaper was now wishing Greenberg and all its Jewish residents a happy new year.

After consulting with a rabbi on his dilemma, Greenberg decided on a compromise approach. He chose to play on Rosh Hashanah, where he hit two home runs.

The next day, the same newspaper ran a photo of Greenberg running the bases with the headline, “A Happy New Year for Everybody.” However, Greenberg made a different decision for Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish calendar, choosing to sit out the game in observance of the holiday.

Greenberg later reflected on Yom Kippur 1934 in an NPR interview: “The only way I would ever think that I might have been a hero in those days was the day I walked into Shaare Tzedek Temple on Yom Kippur. The poor rabbi’s standing on the podium, davening, praying, and suddenly I walk in and everybody in the congregation gets up and [claps]. The poor rabbi looks around — he doesn’t know what’s happening, and I’m embarrassed as can be because it was all totally unexpected.”

Like fellow Jewish baseball star Sandy Koufax, who would face a similar choice decades later, this moment underscored Greenberg’s significant role as a symbol of Jewish pride and identity.

The Hebrew Hammer’s legacy

Hank Greenberg’s final game was on September 18, 1947, capping a remarkable 12-year career that combined power and consistency despite being interrupted by a broken wrist and four years of military service.

Over his career, he maintained a batting average over .300 in eight seasons and led the Detroit Tigers to two World Series championships in 1935 and 1945.

Beyond his Hall of Fame career, Greenberg’s impact extended to changing how many Americans perceived the Jewish community.

As an elite athlete, he broke barriers and challenged stereotypes, becoming a symbol of Jewish pride during a period marked by crisis and antisemitism.

His prowess on the field earned him admiration from his peers, with the legendary Joe DiMaggio once saying, “He was one of the truly great hitters, and when I first saw him at bat, he made my eyes pop out.”

He was a patriot who served two military stints, one of which was voluntary, to serve his country during World War II.

After retiring from pro baseball in 1947, Greenberg became a philanthropist who supported cancer research, helped underprivileged children and contributed to various charitable causes.

In recent decades, interest in Greenberg’s life and career has experienced a resurgence. The award-winning documentary “The Life and Times of Hank Greenberg” was released in 1998, and in 2001, ESPN dedicated an episode of its SportsCentury series to Greenberg.

He was ranked first in the book “The 100 Greatest Jews in Sports: Ranked According to Achievement” in 2003, and his story was shared with younger audiences in the 2022 children’s book “Hank on First.”

Originally Published Feb 16, 2024 04:15PM EST