Shabbat is central to Jewish life and culture. Each week, Shabbat offers Jewish people around the world an opportunity to pause from the daily grind and reconnect with tradition, community, and spirituality.

Read more: Get our guides to all the Jewish holidays.

The renowned 20th-century Jewish thinker Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel eloquently described Shabbat as a time where “the goal is not to have but to be, not to own but to give, not to control but to share, not to subdue but to be in accord.”

Shabbat holds a special place in the hearts of many Jews, regardless of their level of observance. Hosting or attending a Shabbat dinner on Friday evening is one of the most quintessential Jewish experiences.

Let’s unpack the cultural, spiritual, and practical dimensions of this core Jewish ritual.

What is Shabbat? The basics

Shabbat, also known as the “Jewish Sabbath” or day of rest, is observed from Friday evening just before sundown to Saturday after sundown, spanning 25 hours.

Its origins trace back to the biblical creation story: God worked for six days creating the world, and on the seventh, he ceased working, blessed the day and declared it holy, as described in the Torah (Bereshit/Genesis 2:2-3).

At its core, Shabbat is about consciously stepping away from the regular hustle of the workweek and embracing rest, reflection, and reconnection with one’s faith, family, and community.

For those strictly observing Shabbat, this means refraining from activities like driving, shopping, and even using electronics (that includes your phone!) for the duration of Shabbat.

This pause is a chance to disconnect from the routine demands of work and productivity, refocusing on spiritual and communal aspects of life.

Celebrating Shabbat includes rituals such as lighting candles and enjoying a special dinner on Friday night, attending prayer services, singing, and spending quality time with family and friends, all while respecting the spirit of rest and refraining from work-related activities.

More than just a religious duty, Shabbat offers a meaningful opportunity for personal reflection, communal involvement and spiritual well-being.

Those who observe Shabbat often describe its distinctive atmosphere: marked by a conscious shift in mindset and energy, and fostering a sense of intentionality, spiritual growth and family bonding.

How to greet someone on Shabbat

The Jewish community has distinct greetings for every occasion, including Shabbat. Here are the traditional Shabbat greetings:

- Shabbat Shalom: The most widely used greeting, “Shabbat Shalom” translates to “Peaceful Shabbat” in Hebrew. It conveys wishes for a Shabbat filled with rest and tranquility.

- Gut Shabbes: In Yiddish, “Gut Shabbes” translates to “A good Sabbath,” carrying the same warm wishes as “Shabbat Shalom” for those who speak or appreciate Yiddish.

- Buen Shabbat: For those who speak Ladino, a language primarily spoken by Sephardic Jews, “Buen Shabbat” is the traditional greeting, offering the same good wishes as its Hebrew and Yiddish counterparts.

- Shavua Tov: This greeting is used after Havdalah, the ceremony that marks the end of Shabbat. “Shavua Tov” is Hebrew for “A good week,” and it’s a way to wish someone well for the upcoming week.

The central role of Shabbat in Jewish life

Renowned Jewish philosopher Ahad Ha’am famously noted, “More than the Jews have kept Shabbat, Shabbat has kept the Jews.” This captures the profound role of Shabbat in sustaining Jewish identity and culture.

Shabbat is not merely a day of rest; it’s a weekly revival of Jewish consciousness, reflecting the resilience and continuity of Jewish tradition.

Transcending the physical act of resting from labor, Shabbat is a time when the Jewish community collectively steps back from the secular world and engages deeply in spirituality, family, and community. It’s a day that recharges the soul, strengthens communal bonds, and reaffirms Jewish values and identity.

Historically, Shabbat has been a powerful expression of identity and resistance, helping Jews maintain their unique culture and faith despite external challenges. It is a weekly reminder of the Jewish people’s historical, enduring journey and their covenant with God, sustaining Jewish identity through the ages.

The origins of Shabbat

Shabbat’s origins are found in the creation narrative of the Sefer Bereshit (Genesis).

According to the text, after six days of creation, God ceased work on the seventh day, blessing and sanctifying it (Bereshit/Genesis 2:2-3). This act established the seventh day as sacred, forming the basis for Shabbat in Jewish tradition.

Observing Shabbat is an act of “imitatio dei,” where Jews emulate God’s example by resting on the seventh day, reflecting a divine pattern in their weekly rhythm.

In Sefer Vayikra (the Book of Leviticus), Shabbat is described as a day for sacred assembly and complete rest (Vayikra/Leviticus 23:3).

This not only emphasizes the holiness of Shabbat, but also broadens its meaning to include spiritual gatherings and communal holiness. It underscores the communal aspect of Shabbat and its role in building spiritual unity within the Jewish community.

The Ten Commandments, as outlined in Sefer Shemot (Exodus), encapsulate the themes of creation and holiness in Shabbat observance.

The commandment to “remember the Sabbath day and keep it holy” (Shemot/Exodus 20:8-11) links Shabbat directly to the act of creation and underlines its sacred status.

Shabbat observance’s first mention is found earlier in the Book of Exodus. Here, the Israelites receive a double portion of manna on the sixth day to last through the seventh day, teaching them to rest on the seventh day, “a Shabbat of the Lord” (Shemot/Exodus 16:2).

This early experience as a nation ingrained the practice of Shabbat in the Israelites, highlighting its role as both a divine commandment and a natural rhythm of life.

Shabbat’s observance is not limited to the Jewish people; it extends to all of creation, including animals and the land. Shabbat is observed even during critical times like the harvest, highlighting its universal nature as a time of rest and renewal for every element of the created world.

Zachor and Shamor: The dual commandments of Shabbat

Shabbat is shaped by two intertwined commandments: Zachor (remember) and Shamor (observe). These directives form the core of Shabbat observance and the day’s essence.

In Exodus, we find the instruction, “Remember [zachor] the Sabbath day, to keep it holy” (20:8), while Deuteronomy emphasizes, “Observe [shamor] the Sabbath day, to keep it holy, as the Lord your God commanded you” (5:12).

Zachor is about actively recalling what makes Shabbat so special. It’s a call to remember not only the divine rest following the creation of the world but also the Israelites’ liberation from slavery in Egypt, as Devarim/Deuteronomy 5:15 states:

“Remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt and the Lord your God freed you from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm; therefore the Lord your God has commanded you to observe Shabbat.” Shabbat is a weekly reminder of these pivotal moments in Jewish history.

Shamor, on the other hand, pertains to the practical observance of Shabbat. This includes abstaining from work and participating in activities that honor the holiness of the day.

Practices such as resting, praying, singing, enjoying festive meals, and dedicating time to family and study are central to observing Shabbat. This commandment is about distinguishing Shabbat from other days, marking it as a unique and sacred time each week.

Why can’t you use a phone on Shabbat? Refraining from 39 types of work

On Shabbat, the term “work” takes on a specific meaning beyond the usual job-related or physical labor tasks.

In Jewish law, “work” is referred to as melachah, a term that encompasses a broader category of creative work. This concept extends to actions like driving, watching TV, or using light switches. Let’s break it down:

The Hebrew word melachah appears in Bereshit/Genesis 2:2-3 in the context of the creation process: “On the seventh day, God finished that work [melachah] that He had been doing.”

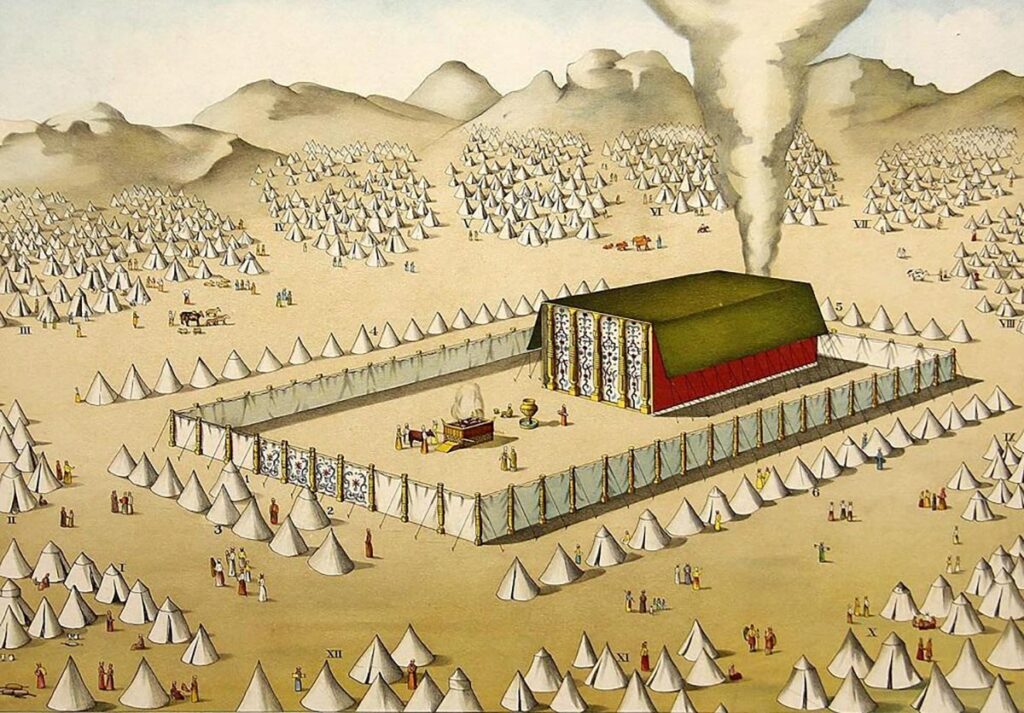

It’s also mentioned in Shemot/Exodus 31:1–11, which details the construction of the Tabernacle. Here, melachah signifies skilled or creative workmanship — creation through creativity — rather than mundane labor.

In the Mishna (Shabbat 7:2), the rabbis list 39 categories of forbidden labors on Shabbat, derived from the tasks involved in building the Tabernacle. These activities, classified as “melachah” and off-limits on Shabbat, include:

- Agricultural tasks like plowing, sowing, and reaping.

- Food preparation processes such as grinding and baking.

- Textile-related tasks from shearing wool to sewing stitches.

- Other activities like building, demolishing, writing, erasing, and kindling or extinguishing a fire.

- Specific rules against transferring objects between domains or within certain public areas.

These 39 categories are broad, allowing them to apply to various modern situations.

For example, in the modern world, the prohibition against “lighting a fire” extends to using electricity. Therefore, actions like switching on lights, using electronic devices, or driving cars (which involve combustion) are considered modern extensions of these ancient labors.

The objective is to interpret these guidelines in a way that resonates with present-day life while preserving the essence of Shabbat.

It’s also important to note that many Jews, even those who may not observe every Shabbat law stringently, find ways to honor the day.

This might include joining a Shabbat dinner, reducing certain activities on Saturdays, or other individual practices that respect the spirit of Shabbat.

What does it mean to “rest” on Shabbat?

In today’s fast-paced, technology-driven world, the idea of a day without social media, work emails or digital distractions is almost revolutionary. Shabbat is a refreshing break from our always-on culture, offering a weekly opportunity for peace and spiritual renewal.

The traditional concept of Shabbat as a time to unplug has gained renewed relevance in recent years, highlighted by books like “24/6: The Power of Unplugging One Day a Week.”

Yet, Shabbat’s notion of rest, described in the Torah with the word menuchah, extends beyond mere physical relaxation.

It’s not just about relaxation or leisure activities but involves ceasing to create permanent changes in the world, a principle rooted in the creation story. This form of rest intertwines relaxation with a sense of holiness, elevating it beyond the physical realm.

Shabbat liturgy, in the Minchah service, describes this rest as one “of love and free will, a rest of truth and faithfulness, a rest of peace and tranquility, and of serenity and security.”

In a society that often equates worth with productivity, Shabbat encourages stepping back from the hustle and reminds us that our value is not solely defined by our output.

It’s a day to reconnect with God and our inner selves and strengthen our bonds within our family and community, fostering a sense of belonging and resilience.

In Jewish mysticism, Shabbat is personified as the “Sabbath bride” or “Shabbat Kallah,” beautifully expressed in “Lecha Dodi” during Friday evening services.

In this beloved song, composed by 16th-century Kabbalist Rabbi Shlomo Halevi Alkabetz, the congregation welcomes Shabbat as if greeting a cherished bride. This metaphor highlights the sanctity and joy of the day, elevating it from a mere day of rest to a spiritual union.

While abstaining from the 39 types of labor symbolizes the physical aspect of Shabbat rest, its spiritual dimension involves engaging in soul-nourishing activities.

This includes prayer, spending quality family time, studying religious texts, and participating in peaceful, reflective activities.

Pikuach Nefesh: Prioritizing life in Jewish law

Traditionally, Jewish law states that it is never acceptable to “break” Shabbat — but there is one exception: pikuach nefesh, or preserving a human life.

This principle asserts that saving a life overrides almost all other religious commandments, including the observance of Shabbat.

Deeply ingrained in Jewish tradition, pikuach nefesh reflects Judaism’s profound respect for human life.

The roots of pikuach nefesh are found in various rabbinic commentaries, most notably on Vayikra/Leviticus 18:5, which states, “You shall live by them [the commandments], and not die by them.”

This verse implies that the primary purpose of commandments is to promote life and well-being rather than to cause harm or danger.

Regarding Shabbat observance, pikuach nefesh has significant implications. If a life-threatening situation arises on Shabbat, actions that would normally be off-limits become not just allowed, but obligatory.

For example, driving to the hospital or making a phone call to emergency services, typically forbidden on Shabbat, are required actions if they can save a life.

Consider a medical emergency occurring on Shabbat. In such a case, any required measures, even if they typically violate Shabbat laws, must be undertaken to save a life.

This principle also extends to emergency scenarios like natural disasters or accidents, where all necessary actions are permitted to save lives, irrespective of Shabbat restrictions.

Preparing for Shabbat

Preparing for Shabbat involves a unique blend of physical and spiritual readiness. Fridays are often bustling with activity, as individuals and families engage in various practices and traditions to set the stage for the 25 hours of Shabbat.

Since cooking on Shabbat is off-limits, meals are prepared beforehand to last throughout the day. Preparations like these are key to creating a peaceful environment conducive to Shabbat’s meaningful rituals and relaxation.

Physically preparing for Shabbat also traditionally includes dressing up in nice clothing to honor and respect the sanctity of the day.

Mentally preparing for Shabbat, on the other hand, is about getting into the Shabbat mindset. It’s about gearing up to embrace oneg Shabbat, or the joy of Shabbat. This concept goes beyond just taking a break from work; it involves actively participating in activities that foster joy, peace, and community bonding.

Oneg Shabbat embodies the essence of the day as one dedicated to rest, family connection, and spiritual enrichment. This approach turns Shabbat into more than a day of rest — it becomes a time of profound celebration and connection.

Lighting candles: The start of Shabbat

Shabbat officially begins with the lighting of candles, signifying the onset of Shabbat. The candles are traditionally lit by women, and they are kindled during the 18-minute period before sunset.

This action, accompanied by a special blessing, marks the shift from the regular weekday into the Shabbat.

At this point, Shabbat has begun and activities prohibited on Shabbat, such as lighting fires (which includes lighting candles), are not allowed.

Kabbalat Shabbat (Friday evening service)

Following the candle-lighting, many head to the synagogue for the Kabbalat Shabbat service, which welcomes Shabbat. This service is characterized by joyful singing and includes a series of psalms and prayers. A key component of the service is “Lecha Dodi,” a poetic song that metaphorically welcomes Shabbat as a bride. This sets the tone for the sanctity and peace of the coming day.

Shabbat at home: Rituals and practice

After returning from the Kabbalat Shabbat service, the traditional Shabbat experience continues at home with several key rituals:

- Blessing the children: Parents bless their children, putting hands over each child’s head saying, to the boys, “May God make you like Ephraim and Menashe” (the two sons of Joseph), and to the girls, “May God make you like Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah” (the Matriarchs).

- Shalom Aleichem: A traditional Ashkenazi song sung at the Shabbat table, welcoming the special angels believed to accompany every Jew on the Sabbath.

- Eshet Hayil: Traditionally sung in many Jewish homes on Friday night, “Eshet Hayil” (A Woman of Valor) is drawn from the Book of Proverbs (Proverbs 31:10-31), praising the virtues of a Jewish woman. This is especially common in Sephardic homes, but it’s also practiced in some Ashkenazi homes.

- Kiddush: The traditional blessing over the wine, sanctifying Shabbat. In Jewish tradition, wine is a symbol of joy and celebration. The blessing over the wine is a moment to reflect on the joy and sanctity of the day.

- Netilat Yadayim: The ritual handwashing, performed before any meal that includes bread, symbolizes spiritual purification.

- Challah (Hamotzi): The blessing over the challah bread, often dipped in salt. The braids of the challah represent the intertwining of the sacred and the secular, while the bread itself symbolizes sustenance and the bounty of God’s blessings. The tradition of using two loaves recalls the double portion of manna that the Israelites received on the sixth day to sustain them through Shabbat in the desert.

In some homes, it is customary to refrain from speaking between washing the hands and blessing the challah (some people hum niggunim, wordless melodies, during this time as it may take several minutes before everyone has washed and returned to the table).

Shabbat dinner

The traditional Shabbat setting includes two candles, usually placed nearby but not directly on the table, along with a kiddush cup and two loaves of challah bread.

The meal typically includes an array of dishes like salads, soup, fish, meat, and dessert, with customs varying across different cultures.

Regardless of the specific dishes, the idea is for the meal to be abundant and unique, setting it apart from the regular weekday fare.

Shabbat dinner is a time for family and friends to come together, enjoy each other’s company, sing zemirot (table songs), and engage in discussions about Torah. It is customary to recite an extended Birkat Hamazon (grace after meals) throughout Shabbat, reflecting on gratitude and blessings.

Shabbat morning services

The traditional Shabbat observance continues on Saturday morning with synagogue services. These services, which can last 2-3 hours, vary in length and format depending on the congregation.

The service includes prayers, piyyutim (liturgical poems), Torah and Haftarah readings, and a d’var Torah, often delivered by the rabbi. If a bar or bat mitzvah is being celebrated, it is traditional for the young person to read from the Torah to mark their Jewish coming of age.

After the service, communities typically hold a social gathering known as an “oneg” or “kiddush.” This gathering can range from a simple affair with wine and challah to a full buffet lunch.

Afternoon rest, Torah study and Mincha

Shabbat afternoons are typically reserved for rest, Torah study, and leisure activities, like going for a peaceful walk or reading a book. This time is an opportunity to unwind, engage in spiritual reflection, or have meaningful conversations on ethical or religious topics.

In the late afternoon, the Mincha service, which includes prayers and another Torah reading, takes place at the synagogue. This service is shorter than the morning service, offering a moment of communal prayer and reflection as Shabbat transitions into evening.

Seudah Shlishit (Third Meal)

Before sunset, a lighter third meal is enjoyed, which may include salads, bread or challah, and other light fare. This meal holds a special place in the Shabbat experience, marked by a more reflective and spiritual atmosphere. It is a time for singing zemirot, traditional Shabbat songs, and engaging in contemplative discussions, allowing for a moment of spiritual connection and introspection as Shabbat draws to a close.

Ma’ariv and Havdalah: Concluding Shabbat

Shabbat officially concludes with the Ma’ariv evening service at the synagogue. After nightfall, the Havdalah ceremony marks the transition between the end of Shabbat and the upcoming workweek.

The ceremony involves blessings over wine, fragrant spices, and a distinctive braided candle, symbolizing the shift from the holiness of Shabbat to the regularity of the week.

In youth groups or camp settings, Havdalah often includes a group sing-along of classic Jewish and campfire songs, making it a particularly cherished tradition.

Shabbat customs vary among different Jewish communities

While the core elements of Shabbat — rest, prayer, and family time — remain consistent across Jewish communities globally, the specific customs and traditions can vary significantly.

These variations are shaped by geographical, cultural, and historical factors, adding a unique flavor to each Shabbat experience. From distinct prayer melodies to diverse culinary traditions, each family and community brings its own unique customs to their Shabbat observance.

Food plays a central role in Shabbat celebrations, and each community has its traditional dishes. In many Ashkenazi homes, Shabbat meals may include dishes like roast chicken, kugel (a noodle casserole), salads, and cooked vegetables.

For Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews, Shabbat cuisine often features dishes like couscous, fish with spicy sauces, and rice-based meals. To learn more, check out these 30 Shabbat foods from around the world.

Shabbat blessings

Here is a guide to several traditional Shabbat blessings:

Hadlakat Nerot (blessing over the candles)

The blessing recited during the candle lighting is:

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה’, אֱ-לֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם, אֲשֶׁר קִדְּשָׁנוּ בְּמִצְוֹתָיו, וְצִוָּנוּ לְהַדְלִיק נֵר שֶׁל שַׁבָּת

Baruch Atah Adonai, Eloheinu Melech haolam, asher kid’shanu b’mitzvotav v’tzivanu l’hadlik ner shel Shabbat.

Blessed are You, Lord our God, King of the universe, who has sanctified us with His commandments and commanded us to light the Sabbath candles.

Kiddush (blessing over the wine)

The kiddush begins with a recitation of the creation story, highlighting Shabbat as a remembrance of both God’s creation of the world and the Exodus from Egypt. This is directly followed by the blessing over the wine:

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה יְיָ אֱלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם, בּוֹרֵא פְּרִי הַגָּפֶן

Baruch Atah Adonai, Eloheinu Melech haolam, borei p’ri hagafen.

Blessed are You, Lord our God, King of the universe, who creates the fruit of the vine.

Blessing over the children

On Friday nights, it is customary in some homes for parents to bless their children.

The blessing for boys is:

יְשִׂימְךָ אֱלֹהִים כְּאֶפְרַיִם וְכִמְנַשֶּׁה

Y’simcha Elohim k’Ephraim v’chi Menashe

May God make you like Ephraim and Menashe (referencing Joseph’s sons who are celebrated for their unity and blessings).

For girls, the blessing is:

יְשִׂימֵךְ אֱלֹהִים כְּשָׂרָה, רִבְקָה, רָחֵל וְלֵאָה

Y’simech Elohim k’Sarah, Rivkah, Rachel, v’Leah

May God make you like Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, and Leah (honoring the matriarchs known for their strength and virtue).

Following these individual blessings, a shared blessing is offered:

יְבָרֶכְךָ אֲדֹנָי וְיִשְׁמְרֶךָ. יָאֵר אֲדֹנָי פָּנָיו אֵלֶיךָ וִיחֻנֶּךָּ. יִשָּׂא אֲדֹנָי פָּנָיו אֵלֶיךָ וְיָשֵׂם לְךָ שָׁלוֹם

Yevarechecha Adonai v’yishmerecha. Ya’er Adonai panav eilecha vichuneka. Yisa Adonai panav eilecha v’yasem lecha shalom (May the Lord bless you and keep you. May the Lord make His face shine upon you and be gracious to you. May the Lord lift up His face to you and give you peace).

Netilat Yadayim (ritual hand washing)

Before the Shabbat meal, and specifically before eating bread, it is customary to perform a ritual hand washing called netilat yadayim.

While pouring water over each hand, the following blessing is recited:

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה׳ אֱלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם אֲשֶׁר קִדְּשָׁנוּ בְּמִצְוֹתָיו וְצִוָּנוּ עַל נְטִילַת יָדַיִם

Baruch Atah Adonai, Eloheinu Melech haolam, asher kid’shanu b’mitzvotav v’tzivanu al netilat yadayim

Blessed are You, Lord our God, King of the universe, who has sanctified us with His commandments and commanded us concerning the washing of hands.

Hamotzi (blessing over the challah)

The following blessing is recited over the challah:

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה יהוה, אֱלֹהֵינוּּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם, הַמּוֹצִיא לֶחֶם מִן הָאָרֶץ

Baruch Atah Adonai, Eloheinu Melech haolam, hamotzi lechem min ha’aretz.

Blessed are You, Lord our God, King of the universe, who brings forth bread from the earth.

Shabbat music

Music and singing play a crucial role in Shabbat, enriching its spiritual ambiance. Here are some key songs, including prayers, piyyutim (liturgical poems) and melodies, that are integral to the Shabbat experience:

Lecha Dodi

“Lecha Dodi” is sung during Friday evening services to welcome Shabbat. Composed by the 16th-century Kabbalist Rabbi Shlomo Halevi Alkabetz, the song personifies Shabbat as a bride, celebrating its arrival with joy and anticipation.

The refrain, Lecha Dodi, likrat kallah, p’nei Shabbat nekab’lah (“Come, my beloved, to meet the bride; let us welcome the Sabbath”), is a beloved tune and encapsulates the essence of welcoming Shabbat.

Shalom Aleichem

Sung at the start of the Friday night meal, “Shalom Aleichem” welcomes the ministering angels believed to accompany every Jew on Shabbat, offering them greetings of peace.

The song’s gentle melody and words, Shalom Aleichem, mal’achei ha’shareit (“Peace unto you, ministering angels”), set a tranquil tone for the evening.

Eshet Chayil

Often sung by husbands at Shabbat dinner with affection and admiration, “Eshet Chayil” (A Woman of Valor) is a tribute to a Jewish woman. This song, drawn from Mishlei/Proverbs 31, extols various virtues and strengths of women, including wisdom, kindness and fear of God, and honors the contributions of women to family life, community and society.

Yedid Nefesh

A devotional poem and song, “Yedid Nefesh” expresses a deep longing for the divine. Sung during Kabbalat Shabbat services, its lyrics by Rabbi Eliezer Azikri in the 16th century poetically convey love for God.

Havdalah melodies

The Havdalah ceremony, marking the end of Shabbat, features beautiful melodies accompanying the blessings over wine, spices, and the Havdalah candle, reflecting the hope for a peaceful and blessed week ahead.

Originally Published Dec 26, 2023 07:18PM EST