Schwab: Welcome to Jewish History Unpacked, where we do exactly what it sounds like. Unpack awesome stories in Jewish history.

Yael: I’m Yael Steiner and my childhood dream was to stay in school forever.

Schwab: I’m Jonathan Schwab and I am in school forever.

Yael: Schwab, I can’t believe I am saying this, but it is our last episode of the season and you have the honors of teaching something to me.

Schwab: I do. And I can’t believe that it’s flown by, but happy to be here. And I’m very excited about this story today ’cause it’s a really interesting one, and a really great way, I think to cap off this season and everything we’ve been talking about for the past couple of months.

Yael: Okay. Well, you’ve set my expectations quite high.

Schwab: Before we get into the story, Yael, I wanna ask you a question. If you had to leave your home and you knew you were going somewhere else, possibly not returning and you could only take a couple of items with you, what would you make sure to bring?

Yael: I feel like I need to answer in a really deep and profound way, um. Photos, some legal documents, maybe my social security card, my passport. Um, anything small and valuable that I can tuck away somewhere.

Schwab: And probably things you carry with you that you don’t even think about, like your credit cards.

Yael: Cash, cash.

Schwab: Things like that. Cash, right, yeah.

Yael: So, if anyone wants to send some, just in case, I’ll leave my address in the episode notes.

Schwab: And you probably didn’t list these things ’cause you might not have them. That’s the life of a millennial, but you know, registration to your car or a deed to your home.

Yael: Don’t have a car. Don’t own a home.

Schwab): Yeah. Right.

Yael: My laptop. that’s probably the most expensive thing (laughing) that I own. And I don’t think my very large television set would be practical.

Schwab: Yeah. So, in the very early second century, a Judean woman by the name of Babatha, left her home and went into hiding with rebels who were part of the Bar Kokhba rebellion. And the Bar Kokhba rebellion probably deserves its own entire episode. But it was a rebellion led by a charismatic leader against Roman rule. This is a couple of decades after the destruction of the Second Temple. But this woman, Babatha, goes with a group of these rebels and they hide out in a cave a few miles away from the Dead Sea. And she brings with her a lot of important legal documents. Because she couldn’t store it on the cloud at that time, so she needed to have them with her. And clearly from what we later figure out, they weren’t sentimentally important to her. These were important legal documents that she probably intended to use in some of her ongoing legal proceedings.

Yael: So, who is she? I’ve never heard of her.

Schwab: You have not heard of her. And she’s not very well-known. We’re gonna talk about Babatha and her story, but part of what’s really interesting is, she’s kind of thoroughly unremarkable in a lot of ways. In contrast to a lot of the characters we’ve talked about, Josephus, Sabbatai Zevi, Dona Gracia Nasi, Saul of Tarsus, Babatha did not have a huge impact on Jewish history. She’s not a major protagonist. She didn’t lead a movement. She didn’t have followers. And the truth is, we only talk about her and know about her because of what her documents tell us about history.

Yael: We’re actually getting a sense of what a regular person’s life was like.

Schwab: Yeah. And that tells us so much about how society functions and, and yeah, and everything, you know, sort of around her in her context, but we also, when thinking about, you know, how do we construct history or how do we think about history. We don’t have her diaries, we just have these legal documents. So, we’ll get to that part of like, what exactly we have. And it wasn’t intended for historians. She didn’t put this aside as like, this is an archive, you know, like we talked about in the Warsaw Ghetto of, of this is like a historical time capsule of what’s happening at this time. She put this stuff and hid it under a rock intending to come back for it, and then didn’t. So we have, her totally unbiased perspective of what was important to her at that moment, that was not intended for anybody else in any way.

Yael: So interesting.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: So, who found these documents?

Schwab: Great question. So, in the 1960s, Yigael Yadin-

Yael: I have heard of him.

Schwab: You’ve heard of him, yeah. General, General Chief of Staff in the IDF. Then, has a second career as, uh, archeologist and historian. Does a lot of excavations and expeditions, with the Dead Sea Scrolls, with a bunch of other sites in Israel. And one of the other caves that they discover around the same area, near the Dead Sea where things were preserved really well partially because of the very, very dry climate, is this cave where a few Bar Kokhba letters, a few Bar Kokhba rebels hid out, and they find some these really well-preserved documents. And based on that, call this cave the Cave of Letters, which is such a cool name.

Yael: That sounds very Indiana Jones.

Schwab: It is very Indiana Jones. And I just wanna say, since you’ve mentioned Indiana Jones that later, so it was originally discovered by Yigael Yadin. And then there was a longer and larger expedition of the caves in the ’90s by this professor, Richard Freund who had a very Indiana Jones look to him. He wore an Indiana Jones style hat, uh, and he actually just passed away very recently. Um, there was a really touching obituary that I read about him, in doing some of this research.

Um, but this Professor Richard Freund, expanded a lot of the work and the research on the Cave of Letters. This is total aside, it doesn’t have anything to do with the main story we’re talking about. But Freund was able to use a lot of new technologies in exploring the Cave of Letters that weren’t available in the ’60s to Yigael Yadin. And they wanted to be able to explore parts of the cave without shifting things aside that might lead to stuff under it being broken. And Freund had an epiphany when we was having a colonoscopy-

Yael: Oh, my gosh (laughs).

Schwab: … that, that a really good device for getting into small places and being able to see parts of things. As an Ashkenazi Jew, I’ve had my fair share of gastrointestinal issues. (laughs) So, when I was reading about this and colonoscopies and its connection to archeology and how it can be used to, to explore caves, this all made so much sense to me. Um, but yeah, (laughs) unrelated to the main story about Babatha.

Yael: So, back to Babatha for a second.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: What language were these documents in?

Schwab: Great question. They were in several different languages. Some of them were in Judean Aramaic, which is like the language that later parts of the Talmud is written in very closely related to Hebrew. Some of it is in a related form of Aramaic called Nabataean Aramaic. And a lot of the documents were also in Greek.

Yael: Oh, interesting.

Schwab: And Babatha, which you’re probably wondering because you probably don’t have a lot of friends named Babatha. That is a name that it seems like, has, has nobody passed down.

Yael: Yeah, fallen out of favor.

Schwab: Yeah. It is some sort of Semitic name. It’s definitely related to Hebrew in some way. And this is from an older style of Hebrew that included that th sound. So, we know how it’s spelled in Hebrew, but we also know how it’s spelled in Greek, which is how we know that it’s pronounced with a th.

Yael: Huh.

Schwab: … with, uh, the Greek letter theta. Which also, is one of those fascinating things that tell us, oh, this is how people were pronouncing things at the time.

Yael: That’s cool. Because modern Hebrew does not have a th sound.

Schwab: Modern Hebrew, in Modern Hebrew she will be called, Babata.

Yael: Yes.

Schwab: And I don’t know why it is that, that name has not maintained its popularity. (laughing) It doesn’t, yeah, it doesn’t roll off the tongue so easily, um.

Yael: It’s not monosyllabic like the, current trend in Hebrew names.

Schwab: Yeah. But this woman, Babatha, had these documents that she had in this satchel that she hid very cleverly under a rock that one of Yadin’s assistants found. He was standing on something and it just seemed too well-placed. They lifted the rock up and they found this leather satchel with these incredibly well-preserved documents that are 1,900 years old, and meticulously organized and kept. And these legal documents, it gave us so much information about Babatha. And at the same time, so little information about her.

We don’t know really how she felt and what she looked like. Any of those sort of biographical details, but we know so much about her life and about the things that she was actively engaged in doing. A lot of which changed some of our perspectives about how society functioned at the time, especially with regards to gender and agency.

Yael: So, I wanna hear all about what she had-

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: … in this satchel. But what I’m really taking away from this right now, is the importance of a good handbag.

Schwab: Yes. Preserving your documents is incredibly important, yeah. And a good, I don’t know, like-

Yael: You might not be a handbag aficionado, but I’m just-

Schwab: No, but I have a messenger bag that I take to work every day. And I research very carefully what is a really good bag, you know, that, that can commute well with me, that can withstand weather. And yeah, this is, this is not simple stuff.

Yael: I’m gonna think about Babatha when I buy my next purse.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. I, I feel like there’s an opportunity out there for someone to l- If, if we can’t get Babatha back as a common Jewish name, maybe getting the Babatha purse.

Yael: Babatha satchel, amazing.

Schwab: The Babatha satchel, yeah.

Yael: Okay. So, sorry, you were about to say something about how she teaches us about gender, and then I cut you off to talk about handbags.

Schwab: So, we have these 35 different documents. I’ll tell you what some of them were, and sort of what we know about her life. And they’re in a bunch of different languages, but none of them are written or signed by her. They were all written or signed on her behalf, which leads us to believe that she probably could not read or write this.

Yael: I was just about to ask you, do we even know that she knew what these documents said?

Schwab: She knew… It’s very clear from the documents that she really knew what she was doing. She knew how to avail herself of lots of different legal means. She understood finances incredibly well, but she maybe did not know how to read or write. Um, certainly in at least one of these languages, maybe in any language.

So, from these documents, here’s the bio of her life that we can reconstruct. Um, she was married twice, we know that. The first of her two marriages, which probably took place when she was very young, probably she was somewhere in the age of, of 12 and 15 when she got married the first time. And her first husband’s name was Jesus. It wasn’t that Jesus. That was a really common name at the time. And we know that from other sources, but we definitely know that from this source because her first marriage was to a man named Jesus, son of Jesus.

Yael Hmm.

Schwab: Uh, and she had a son with this guy, Jesus.

Yael: Named, Jesus.

Schwab: And the son’s name was Jesus too.

Yael: Wow. It’s less stressful than reading a baby name book.

Schwab: Yeah. Jesus is also a name that has not retained its popularity in the Jewish community like Babatha.

Yael: Like, Adolf.

Schwab: And like, Adolf. I have a great, great grandfather whose name was Adolf. I don’t think that’s a name that I’m gonna be using for any of my children. Um, so she had a son with Jesus. And when that son was very young, again not the famous baby Jesus, her first husband died. And this is one of the first legal battles she gets involved in. As a woman, she was very limited in what property she could actually own and what holdings she could have, even though she inherited quite a bit from her father in the form of date palm orchards, which I spent a lot more time reading about date palm orchards than I thought I ever would. Date palm orchards were, were pretty important ’cause that’s, that like, was, could be a source of a lot of wealth.

Yael: Yeah. Dates are expensive.

Schwab: Dates are expensive. But owning a date palm orchard meant you had to have a significant amount of money because you needed to put a fair amount of work into caring for date palms. You need workers who can irrigate them, and then collect the dates. All of that. It’s one of those things where, if you’re rich, you can make money off of it. But if you don’t have money, you can’t sort of get into the date palm game.

Yael: High barrier to entry.

Schwab: Yeah. So, she inherited date palms from her father, but when she married, those sort of fall into her husband’s holding because she can’t really own property in her own name in some ways, in this time. Um, so her husband dies and she is responsible for taking care of this infant. And the courts sort of use this system of guardianship, which is really a Greek concept where someone can sort of hold her husband’s properties on her behalf. And then pay her some of those proceedings to use for the care of her child which is, you know, his, Jesus’, son who should be cared for and should get that estate, but isn’t yet old enough to inherit it outright.

And that’s where she gets into this first legal battle where she essentially sues these guardians and this system, saying, “I actually think I should be entitled to a higher amount of interest,” from these holdings that they have.

Yael: I love her already.

Schwab: Yeah. Yael Steiner, you will love this person. As a woman, as a lawyer, as a person who knows about finance, like, she is an incredible role model.

Yael: Amazing.

Schwab: And one of the arguments that she makes and this tells us a lot about just sort of how she understood things really well, she said, “Actually, what we should do is combine my husband’s holdings with the holdings that were left to me by my father because that larger estate, I’d actually be able to earn a greater amount of interest.” I think it was, she argued that she could get 9% interest instead of 6% interest because it was a larger combined estate. And like, she’s arguing or, or whoever’s writing it on her behalf is talking about like, complicated financial instruments in second century Judea.

Yael: She knew what she was doing.

Schwab: Yeah. She definitely knew what she was doing. The assumption from historians is that her father probably taught her some of these things. She didn’t just know how to collect dates from date palms. She knew how to leverage date palm fields into some, you would know this better than me, into some sort of like, I don’t know, collateralized debt, maybe is the term for it. I don’t know exactly, you know, what it is that she’s doing.

Yael: Sounds like, some coupon yielding-

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: situation.

Schwab: Yeah, exactly.

Yael: Shout out to dads who teach their daughters stuff.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: Side point.

Schwab: Yeah. Her dad made a pretty big difference-

Yael: Amazing.

Schwab: … by teaching her some of these things. But she loses this legal battle. And we know she loses this legal battle because we know exactly how much money she was arguing she should get. And we know that she also kept receipts of how much money she received presumably to use as evidence in a later battle, saying you know, “I argued this. I said, I should have gotten,” it was two, uh, dinari, I think is the currency at the time. And she was getting two dinari a month. And she said, “Really, I should be receiving six a month,” and she saved this receipt. But based on the numbers on the receipt, we can see pretty clearly that she continued to receive the two per month. And it seems like she saved that for the purposes then of, of still being able to sue in court and say, “Hey, I still am owed more money. I wanna appeal this decision and I want the back pay on all of this that I was entitled to.”

Yael: You go, girl.

Schwab: Yeah, seriously. Then she got married a second time. And she married this guy, Judah. And this guy, Judah, was no match for her when it came to financial maneuvers. And it seems like he did not know how to manage his money well, and was constantly like, falling over himself and losing all sorts of different things. And he ends up borrowing money from her dowry, in order to pay. And we know this because of the dates on these documents that she held because she was pretty organized and responsible of all of these things. We know that he borrowed a significant amount of money from her. And very shortly afterwards like, two or three months later, paid the dowry to marry off his daughter. So presumably, he borrowed money from her to pay the dowry, you know, for that daughter who was married off.

Yael: Who was not Babatha’s daughter.

Schwab: Correct. Not only was it not Babatha’s daughter, that daughter who was from his other wife, Miriam, that marriage was still ongoing at the time. This, this was, uh, polygamist marriage-

Yael: How lovely.

Schwab: And in addition to having a series of failed financial ventures, this guy, Judah, also passes away. And then Babatha gets into legal battles with her co-wife-

Yael: A-ha.

Schwab: over different parts of the estate. And Babatha seizes part of this and saying, “I’m actually owed this because he borrowed this money. And I’m seizing this part of his property to repay that debt that he owes me.” And she also gets into a legal battle with Judah’s sons, also from that first marriage. And she, she’s going to court against all of these people. And not always winning, but she definitely persistently continues to get involved in all of these different legal battles. And clearly, knows her way around the court, knows what she’s talking about. And these are different types of courts. Sometimes they’re Roman courts, sometimes they’re Nabataean courts. She’s talking about Jewish laws, so like, she’s well-versed in a bunch of different systems. And she’s using all of them.

Yael: It’s fascinating. I mean she obviously comes off a little bit as a litigious person.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: But what I’ve gotten from what you’ve taught me so far, it seems like she’s just fighting for what’s rightfully hers. She’s not seeking out things that are not well within her rights.

Schwab: Absolutely, right. And like, she grew up, she inherited a fair amount of wealth from her father. And then she, in this first round of legal battles with her infant son, she wants her infant son to be able to grow up comfortably the way that she did based on the money that she inherited and that his father left. And she really fights to get what she deserves and what she is owed. The way it’s described in one of the essays that I read is, she was illiterate but she was no wallflower.

Yael: Oh, interesting.

Schwab: She was not held back by the things that she did not know or could not do. She certainly was not held back by the fact that she was a woman and she still used everything that she could do. And, she pushed the envelope, it seems like, in a bunch of ways. And when she didn’t get the answer that she wanted, she tried another route, and she kept fighting for the things that she deserved. And it’s very different than the view of women that we might get if we only look at male authored and male-centric writings from the time of just like, how gender was treated, what the place of women was in the society. from what she put together, we have a very, very different view on how she saw herself. And you know, how it seems like, she was functioning.

And none of the documents were saying anything like, well, here’s this woman, doing something that no other woman has ever done. So, it seems like, this is something, you know, not every single woman was doing. But that women could avail themselves of all sorts of different ways to claim agency and claim property, even when it wasn’t part of the existing structure.

Yael: So, the indication is that she wasn’t just thrown out of the court system simply by virtue of being a woman. Like, she did actually have the opportunity to make a case.

Schwab: Mm-hmm, yeah, yeah. And when she needs to be represented by someone else on her behalf, she’s represented by someone else on her behalf. But yeah, she definitely had that opportunity to make her case. And there’s a couple of other documents that they are sort of a little more difficult to understand what their place is. There’s another woman who was with her. There was a couple of documents from this other woman that maybe she was holding on this woman’s behalf. Maybe it was sort of like, a mentor relationship with this other woman, Salome, who she took under her wing and was sort of like, “Look, Salome, here’s, here’s how you can do some of the things that I’m doing.” But she also has in the set of documents that she put away, a bill of sale when one of her brothers sold a donkey to another one of her brothers. And, and like, why would she have this document? It’s very puzzling, (laughs)

Yael: Because they would have lost it.

Schwab: Right. So, different historians have different answers. And one of them is like, maybe they couldn’t get along. Maybe she was like, the middle person between them. Or maybe it was just like, she was the most responsible person and they trusted her. And they were like, “Look, we’re, we’re gonna, (laughs) we’re gonna lose this document. But Babatha, you are great at holding onto stuff, so hang on to this donkey sale letter for us.”

Yael: So interesting. Do we know at what stage in her life the Bar Kokhba rebellion took place, and she had to go into hiding?

Schwab: We know that she was an adult. We don’t know how it is that she wound up with the rebels. We know that she was there, right. Like, she clearly put the documents in the cave. Clearly meant to come back for them. Was she involved in this rebellion? Was she a political sympathizer? Did she believe in the rebellion? Did she go to the cave because, you know, the Romans were just coming around and everybody was in danger because of the rebellion, and it was just a safe haven for her? We don’t know any of that.

Yael: Because it wasn’t a business transaction, she didn’t have it in writing.

Schwab: Yeah. Again, there’s no diary. She didn’t write down, here’s what I’m doing. And she didn’t buy anything from Bar Kokhba.

Yael: Mm-hmm.

Schwab: If she had bought something from Bar Kokhba, we’d have it.

Yael: She would have kept the receipt.

Schwab: Yeah, she would have kept the receipt. So, we don’t know how is it that she wound up in this cave with these rebels. But we also don’t know what happened to her after. There were human remains in that cave. Some of them were women. Some of them were children. It could be that one of those is Babatha. It could be that she left the cave, hid her stuff under this rock. And went somewhere else, fully intending to come back, and, and met her end somewhere there. We have no clue what happened to her after this.

Yael: So, this is really a historical find that doesn’t teach us anything about the military situation that was going on there, about the Bar Kokhba rebellion. But it does teach us about the possibilities that were open to women at the time.

Schwab: Mm-hmm, yeah.

Yael: Simply by virtue of looking at her, you know, balancing her checkbook essentially.

Schwab: Yeah, yeah. but it doesn’t just tell us about women. We don’t have this detailed in archive for any person living at that time. Like, when it was found, I don’t know if it was fully appreciated right away. Um, but this is the most complete set, well-preserved set of documents, from any one individual person living in Israel at that time. Like nothing compares to this in terms of just like, how we can view history through the eyes of an individual person.

Yael: Did they have any personal documentation that they found? Like, were there ketubahs or birth certificates or death certificates?

Schwab: Yeah. So, there are no birth certificates or death certificates, but her ketubah for her second marriage to Judah is there. Her ketubah for her first marriage is not. And that’s one of those questions that people have because it’s just like, we got to assume that if it wasn’t there, it wasn’t there for a reason. Because this is a woman who did not lose documents, we’re pretty sure. Like she’s got to have had one, right? But that’s also really like, this ketubah from her second marriage like, this is one of the things that comes up a lot. A lot of historians point out like, the ketubah includes a line like, she is married according to the law of Moses and Judean tradition, which is like, pretty similar to the language that, that we use now, in modern marriage.

Yael: So interesting.

Schwab: Yeah. So, her ketubah was there. But birth certificates, death certificates, no. They didn’t have anything like that at the time. In addition to, these like, legal documents and, and records of depositions, I guess, they certainly weren’t calling them that, she also has like a registration of her property from some sort of Roman survey at the time. Which is like, comparable I guess, to like the deed to a home.

Yael: Like a deed, yeah.

Schwab: Yeah, right.

Yael: Was all of this stuff written on papyrus?

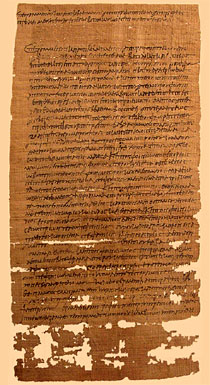

Schwab: Yes. So, this was all on papyrus. These are the, the 35 Babatha papyri-

Yael: Oh, wow. Nice word.

Schwab: … which is the plural of papyrus. Yeah. And they’re labeled, I think they’re in the Israel Museum still. I don’t think that they’re on display. But if you, I don’t know, you could maybe ask if you could see them as researcher or something like that.

Yael: Yes. Now, that I’m a world famous historian.

Schwab: Yeah. They’re named after Yadin, who led the expeditions. So, they’re numbered 1 through 35. They’re referred to in academic text as like, Yadin, P for papyrus, P.Yadin 1-

Yael: Mm-hmm.

Schwab: … through 35.

Yael: Very cool.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: Very, very cool. I mean I’m just thinking now, about how disorganized I am. And how no one would ever know anything about me.

Schwab: We can’t all be a Babatha.

Yael: There would need to be some serious forensic accounting to figure out what was going on with me.

Schwab: Yeah. And it’s interesting to think about her, not just comparing ourselves to her, but comparing, you know, like I said at the beginning, we’ve had this whole season, we’ve talked about so many interesting characters. And thinking about how she’s, how she’s different, but in some ways, how her story is similar to them.

Yael: I assume that, you know, if she’s hiding out with these rebels during the Bar Kokhba rebellion, there were fighters with her. There were probably military leaders with her. Or at least people who might have had the opportunity to shed some light as to what was going on in the military or political sphere.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: But none of those people were nearly as organized, (laughs) um.

Schwab: Yeah. But there are, there are Bar Kokhba letters both in this Cave of Letters and in other places. There are letters, you know, about military maneuvers and things like that, that we have recovered. But yeah, nothing, nothing as organized and meticulous and systematic.

Yae: Nobody else brought their records with them into the cave.

Schwab: Right. And there were people who were writing, but from a different standpoint, right. Like, we know, you know, way back, this was our first episode, but Josephus writes the history of this. But he writes it as a historian, you know.

Yael: Right.

Schwab: And that was like, so much of what we talked about. It was like, his perspective that he’s bringing to all of this. And it was intended for people to read about and understand. And Babatha is so different because the intended audience was not history at all, in any way. The intended audience was the court, so that she could get what she wanted.

Yael: Thinking back to some of our other episodes and a lot of what we talked about is, you know, who is a Jew for the purposes of studying Jewish history. Not for anything political purposes or religious purposes-

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: … but in terms of when we think about Jewish history, who are we thinking about. Besides her ketubah, which you mentioned, do we have any other indications in these legal documents about her Jewish life?

Schwab: Yeah. Great question, yeah. And, and like, connects to so much of what we spoken about. It was clear that her Jewish identity was a huge part of who she was. The legal documents do not talk about, you know, oh, she, I don’t know, keeps kosher, or keeps the Sabbath or any of those things. But we do know that a lot of the legal maneuvers that she was making were based on Jewish law or Roman law or, you know, using one of the other, which tells us a lot about how she, as a Jew, existed in both at the same time, right. Like, she was a Jew and there was this Jewish legal system and structure that she availed herself of. But also, then she also would go to the Nabataean court if she didn’t get the answers she was looking for from the Jewish legal system.

Yael: Fascinating.

Schwab: Yeah. Which I think does say a lot about how she saw herself as Jewish. And connects to so much of what we’ve spoken about of, of Jewish identity very often being about having more than one identity at the same time.

Yael: Yeah. And how you navigate between those two, going back to Napoleon and the emancipation of the Jews. And figuring out not only where you fit, but also it seems like she was figuring out how to leverage the best of both societies to her benefit.

Schwab: That was exactly the next connection I wanted to mention, was exactly that, of just like, how the legal structures of our surrounding society and our Jewish identity are, are often inseparable. And navigating, you know, the space between the two of them is a huge part of the Jewish story of the last 2,000 years.

Yael: And I think so much of being an American Jew and enjoying the immense privilege of the freedom to exercise your religion, is about navigating those two spaces, the one space in which you are expressly exercising your religious rights by partaking in prayer, or partaking in public ritual. But the other side being the side where you’re expressly not participating in things that don’t resonate with you and also, the part where you say, “I’m just another American because we do not distinguish between people of different religions here, because we’re all on the same plane.”

Schwab: Mm-hmm, I love that.

Yael: Like, on the one hand, I wanna be someone who can pray the way I wanna pray. But on the other hand, I wanna be just like everybody else.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: And it’s a conundrum sometimes.

Schwab: Yeah. Can you have both? Can you really do both of those things?

Yael: You know like, politicians often will wanna talk to a community and say, “I wanna talk to the Jewish voters. And I wanna talk to them about what they’re concerns are.” And sometimes that’s really important. But sometimes I just wanna be spoken to like every other voter.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: Like, I have the same concerns as every American when it comes to things that aren’t in the religious sphere. And that I need to navigate those two spaces.

Schwab: Yeah. This is a reference that’s probably going to be very dated, probably very shortly, but a great way to do that as a politician I think, is to sort of just identify with every community at the same time. There’s a very recently elected member to Congress who, uh, who could speak to the Jewish community ’cause he is Jewish, he claims. Uh-huh.

Yael: Jew-ish.

Schwab: And, and Jew-ish.

Yael: I’m so curious if he’s still gonna be in Congress by the time this episode comes out.

Schwab: Right, (laughs) I was gonna say, if someone is listening to this a year or two from now, right, like, even perhaps when it comes out, we’ll see.

Yael: Or a week or two from now, when it’s actually released.

Schwab: Yeah. Maybe one day that will be a topic for Jewish History Unpacked. The George Santos controversy and the nature or Jewish identity in 21st century America.

Yael: But how unbelievable is it, when you think back to all of the stories we’ve told this season and all of the stories that we still wanna tell and explore, and the depth and breadth of Jewish history, that someone ran for office in the United States of America and thought it would be to his benefit to say that he was Jewish. Can you imagine our ancestors ever thinking that that would be the case?

Schwab: But remember, I think this is episode four, right, the story of the Khazars and their conversion out of political expediency and saying like, “I don’t know, it seems like maybe it would be beneficial in this particular time and environment to identify as Jewish. That might be helpful.” Maybe it’s a sort of similar type of thing. In this particular moment, identifying as Jewish has some sort of benefit that it’s a good thing.

Yael: It’s fascinating.

Schwab: But it does seem surprising and, and you know, I mean compared to all the other episodes.

Yael: Yeah. I mean, we are very privileged to live at a time in world history when being Jewish is arguably the safest it’s ever been. Obviously there are incidents that challenge that thesis.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: And the fact that people at the highest levels of power in the most powerful country in the world, hmm, we can make an argument about that a different day, um, are talking about the benefits of leveraging Jewish identity, is something-

Schwab: Mm-hmm, yeah.

Yael: … that I think even my grandparents could not have fathomed.

Schwab: Yeah, right.

Yael: You know, people who ran for their lives from their own homes for being Jewish, people who did have to make that decision, what would you take-

Schwab: Right.

Yael: … if you were leaving?

Schwab: And they had to think about all sorts of ways to try to, to conceal their Jewish identities for safety.

Yael: For sure.

Schwab: Yeah. Like, how radically different things are now.

Yael: I mean, we’re very blessed, which doesn’t mean that we sit on our laurels and don’t try to improve things where they need to be improved. But if there’s one thing I’m taking away from the George Santos story, is that I guess there are people who think that being Jewish is pretty good.

Schwab: Yeah. It’s nice to hear.

Yael: Uh, fascinating.

Schwab: We’re blessed not just as Jews and Jewish Americans, but I also wanna take a moment winding down this season and say, we’re blessed to be working on this podcast. It’s been an incredible journey. I feel really blessed to be working with you, Yael.

Yael: Oh.

Schwab: You’re an amazing cohost. And I, I’ve, I’ve really enjoyed-

Yael: I feel very much the same about working with you. It’s been so much fun. And a highlight of my week. You’ve been great. Your family has been an invaluable resource for criticisms and enthusiasm.

Schwab: My six-year-old kids who’ve I’ve mentioned a bunch of times, are very avid listeners of the podcast. And they have a lot of thoughts.

Yael: They are the most well-educated six-year-olds on the topic of Jewish history, I would venture to guess.

Schwab: Yes, definitely.

Yael: I also wanna give a shout-out to our wonderful producer, Rivky.

Schwab: Yeah. She is amazing, She makes this podcast really as good, as it can possibly be. And better, I think than either of us ever imagined it could be. And we also wanna thank Dr. Henry Abramson who is our education lead. And is just an incredible font of wisdom and guidance and mentorship.

Yael: And Rob, our awesome editor who makes us-

Schwab: Yes, and shout-out to Rob.

Yael: … sound a lot smarter than we are.

Schwab: And last but not least, definitely thank you to all of the listeners who’ve been with us on this journey. It would have been worth it, even if only my kids listened to this podcast because it’s been great to learn so much over the course of the past couple months. But it has really been amazing how many people we’ve reached and how many people have listened. And, and have given us feedback and suggestions and ideas. We love it, keep it coming. Thank you so much for being with us.

Yael: I might cry.

Schwab: Stay tuned, there’s more Jewish history and there’s more to unpack. So, we’re looking forward to continuing this conversation.

Yael: The satchel is still full. Plenty of information to still look at, which I’m really excited to do.