Schwab: Welcome to Jewish History Nerds where we do exactly what it sounds like, nerd out on awesome stories in Jewish history.

Yael: I’m Yael Steiner and my childhood dream was to stay in school forever.

Schwab: I’m Jonathan Schwab and I am in school forever. And I apologize if the audio sounds different for today because I am recording not in my usual location but actually in the school that I am in forever. (laughs)

Yael: It’s almost like we have full-time jobs.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: Crazy. Schwab, I’m excited to hear what we’re going to talk about this week.

Schwab: Great. I’m really excited also. We had a bit of a slight hiatus in our recording schedule and part of that was there was so much to research about this topic.

Yael: I’m excited.

Schwab: The Spanish Golden Age, also known as La Convivencia.

Yael: That sounds very elegant.

Schwab: Yes, it’s a remarkable period in history where at a specific time and in a specific place medieval Jews had unparalleled and unprecedented freedoms and access within society and they used those opportunities to create a flourishing of a unique type of Jewish culture.

Yael: And this was taking place in Spain?

Schwab: Yes, correct.

Yael: And the time?

Schwab: And the time, It definitely was no earlier than the 8th Century, specifically the year 711 and it definitely ended by 1492. The real height of it was around the 900s and 1000s, so the 10th and 11th centuries, the early 12th centuries were definitely the best parts of it.

Yael: That’s a pretty long time.

Schwab: Yeah. This is multiple generations. This is a couple of hundred years in a country in Europe where Jews had a very different experience than they did elsewhere during those Medieval times.

Yael: How did Jews get to Spain?

Schwab: Love that you would ask me that (laughs) because we know that there are Jews in Spain going all the way back to the first century. And there’s a couple different pieces of evidence for that. One of them, callback to one of our old friends from season one, is that in the New Testament that Paul talks about among his many travels going to Spain. So we know in the time of Paul there were already Jews in Spain and then there were a couple of things not much later than that. A very old grave that says, you know, here lies this very young girl, daughter of this person who was a Jew, um, that we know how old the grave is. It’s dated properly and and that’s verified and everything so we know Jews were in Spain from at least as far back as the first century and that community grew over time. Like it’s not like there was one huge wave of immigration.

Yael: And they gained enough in numbers and in power that by the 8th century they seem to have a lot going on.

Schwab: Uh, yeah. So prior to the year 711 which is a very easy year to remember, if you’re a fan of Slurpees, the area that we now know as Spain was largely under a series of Kings for a couple of hundred years called the Visigoths.

Yael: Mm-hmm. Heard of them.

Schwab: And the Visigoths converted at some point during their rule to Christian Catholicism. And as Catholics, they had it in for the Jews pretty bad. Um, there was a lot of persecution. Jews had very few rights, were barred from a lot of things and were very frequently punished for their infractions. And for whatever reason the favorite punishment of the Visigoths was public amputation.

Yael: Wow. That’s really, really awful.

Schwab: Yeah. So that’s the state of Jews in Visigothic Spain prior to 711 and they were not huge fans of the Visigoths.

Yael: Understood.

Schwab: Yeah, for understandable reasons. Starting in 711, Muslim armies begin to invade Spain from the south coming from North Africa over the Strait of Gibraltar, and taking more and more territory in Spain. And there’s a whole question of what was the Jew’s role in this Muslim Conquest exactly? There’s no question that the Jews definitely were happier with this emerging Muslim rule under which they seem to have a much better position.

Yael: Mm-hmm.

Schwab: There was an accusation that took the form of something like the Jews have invited the Muslims and are now making it easy for the Muslims to sort of conquer all of this territory.

Yael: They were helping.

Schwab: Yeah, they were definitely not hindering this Muslim conquest. They certainly were very open to rule by Muslims. And we don’t have a ton of evidence that they were, like that invitation thing I don’t think happened, and like smacks a little bit of like an anti-Semitic trope to me that the Jews are like a fifth column in the country that’s helping the enemies of the country.

Yael: But I would think that it doesn’t really matter who they’re inviting or bringing in if they’re living under persecution.

Schwab: Right.

Yael: It’s human nature to want to improve your life circumstance.

Schwab: Yes, yeah, totally. I don’t know. It reminded me of like a Germany interwar thing like, “Oh, the reason Germany lost World War 1…

Yael: Right. it’s like the Jews are the invisible hand-

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: … pulling the strings. Interesting.

Schwab: And in this case, their hands had already been cut off.

Yael: I was gonna say (laughs) if they really had all that power, they probably would have implemented it earlier.

Schwab: Right? Yeah.

Yael: But I understand where you’re coming from.

Schwab: That is always the response that I have to every antisemitic, you know, idea or stereotype. If Jews had that much power, do you think this is what it would look like?

Yael: Exactly. But you know, there’s no winning that debate.

Schwab: So eventually under this Muslim rule, they come to have a lot of access I said and one of the things that they’re able to do is individuals are able to rise almost to the highest levels of arts, military, political fields, science, medicine. And at the same time and very often the same individuals are deeply invested and involved in the world of Jewish learning, Torah learning scholarship, which is very rare. Usually it’s one or the other, right? Like there are plenty of prominent Jews.

Yael: Right. Like Maimonides I’m assuming emerges in this era.

Schwab: Maimonides is one of them. We’re gonna spend a little less time on him because I think he’s better known and there’s so much out there about him.

Yael: But, you know, I know that he was a physician.

Schwab: Exactly.

Yael: And obviously one of the greatest Jewish scholars in history. So he clearly embodies that duality which as you mentioned is really uncommon particularly today in observant Jewish circles, there is a huge divide.

Schwab: Yes, right. There are the incredibly learned Jewish scholars of the world but, but by necessity or by design or, or just by happenstance they tend to be if anything very isolated from the world.

Yael: Correct.

Schwab: And the reverse. There are Jews who are at the highest levels of medicine, science, politics but usually they’re not observant or certainly not like deeply involved in that world of scholarship.

You know, just trying to think about how I would explain this in present day terms and I was thinking, okay, what if Joe Lieberman who was a senator and vice presidential candidate and was a prominent Jew who was observant and talked about his observance. But imagine if in addition to all of that, imagine if he also gave a Talmud lecture or had a podcast about Talmud that had tens of thousands of listeners because it was seen as one of the best lectures out there, and he was also treated as a rabbi of great renown and great scholarship.

Yael: Right. We don’t have too many, if any, symbols like that anymore.

Schwab: Like that, yeah.

Yael: I’m sure people will write in and be like, “My rabbi is (laughs) also a doctor and he’s amazing.”

Schwab: Right. The flip side of this that I was thinking about is, imagine if Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks who was an incredible Jewish thinker who was able to articulate philosophy about Judaism that reached Jews and non-Jews alike and was appointed to the House of Lords in the United Kingdom. But imagine if in addition to all of that, his appointment to the House of Lords came because he also had decades of not just military service, but military leadership, like he had been a general in the Army and was decorated. That’s the type of thing that Jews were doing in Muslim Spain.

Yael: Wow.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: It’s almost like if you don’t have social media you have time to really better yourself.

Schwab: That’s why they had all the time because they weren’t busy on Twitter. And because there was so much less history to study. I think about that all the time. People living a thousand years ago had it so easy because so much less had happened already.

Yael: Excuses, excuses. But I hear you.

Schwab: Going back so we’re in 711, the Muslims come in. They begin to conquer parts of Spain. They refer to it as Al-Andalus.

Yael: Mm-hmm.

Schwab: The area had been known as Andalusia which is still an area of Spain.

Yael: Mm-hmm.

Schwab: The Muslims in Al-Andalus under their series of assumptions and rules about the way a society should be, they treat both Jews and Christians as a form of protected minority. They do not have all of the privileges that Muslim citizens have. They’re considered Dhimmi-

Yael: Right.

Schwab: And they have to pay a specific poll tax which is different than Muslim citizens that’s called the jizya. There’s all sorts of rules that they can’t like be, a Jew can’t sit higher up than a Muslim. Their synagogue cannot be built higher. Thank you, for all of these things, thank you to Jews In the Lands of Islam. A course I took 10 years ago, and if memory serves, actually did quite poorly in.

Yael: Well, you have a chance to make up for that today.

Schwab: Yeah. I will send this podcast to Professor Sadiq and tell him, “Look where I am now.”

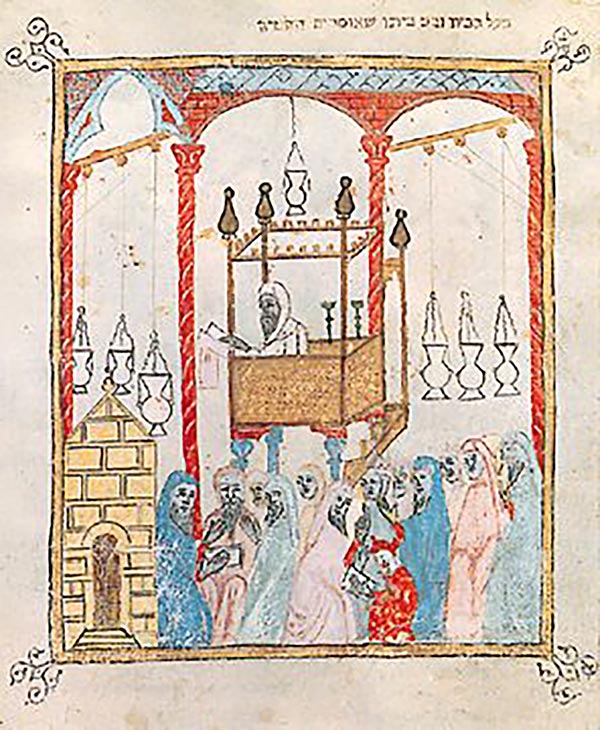

Yael: Fantastic. So I actually think I knew that about the synagogues not being allowed to be higher than the mosques. I visited some really old synagogues in Spain and a lot of them are built into the ground. Below ground, maybe for that reason.

Schwab: Yes, yeah. And also, you’re not allowed to rebuild the synagogue if it fell down, but like many things, one of the reasons we know about all of these policies is that things were constantly getting published saying we need to be stricter in our enforcement of these policies.

Yael : Mm-hmm.

Schwab: Which a little bit sounds like-

Yael: People weren’t respecting that.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: So Jews and Christians are being treated pretty well.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: And I guess that allows them to start building foundations for success.

Schwab: Yes, yeah, yeah. And then it gets to the why of all of this. Like what is it that was so different? Why is it that this functioned differently.

Yael: Mm-hmm.

Schwab: And there’s sort of two large theories that are probably both correct, but they’re different ideas, of like why is it that this worked so much better for the Jews in this case?

Yael: Mm-hmm.

Schwab: And it didn’t elsewhere. So the first is this notion of triangulation or a, or a triangular society that this was a rare instance. There were plenty of other Muslim lands where Jews were living under Muslim rule. But in most of those other places there were very few Christians, and there were plenty of Christians, but in most of those places there were a few Muslims. This is a rare example of a society where they’re not equally proportionally represented, but there’s certainly a large enough contingent of all of them that it feels like society operates around all three of these religions working at the same time.

Yael: Interesting. It’s almost like they’re a buffer.

Schwab: Yeah. Right? So to some extent it could be a buffer. I don’t think that’s the full… It’s not, “Oh, the Muslims were so busy oppressing Christians or dealing with Christians that they didn’t have time to be anti-Semitic.

Yael: Right, right, right.

Schwab: I think more along the lines of like the whole society has to function in this diverse way. You have to recognize multiple different perspectives, and there isn’t a binary of power versus oppression.

Yael: Got it.

Schwab: There’s like multiple constituents. And again this is definitely a huge caveat here. When we say diversity or pluralism or respect, not 21st-century versions of those things.

Yael: Right.

Schwab: But way ahead of their time for the 8th century, 9th century, 10th century. That’s the first idea, explanation. The second is that and again this doesn’t fully account for why this might not have happened in other Muslim lands, but that Jews under Islam is very, very different than Jews under Christianity. Christianity emerged from Judaism and was in therefore much greater conflict with it, needed to distinguish itself from Judaism in many ways, was much more threatened by Judaism. Like burnings of the Talmud because of the things that the Talmud says about Christianity. The Talmud doesn’t really discuss Islam, uh…

Yael: Mm-hmm.

Schwab: Mostly because it wasn’t around, I believe at the time most of the writing of the Talmud but also it was just… It, Islam was less threatening to Judaism. Judaism was less threatening to Islam. The two religions are, function much more similarly in terms of being based a lot more on, on rituals and practices, and behaviors.

Yael: Mm-hmm.

Schwab: And much less on faith and theology alone. Uh-

Yael: Right. Man is not saved by faith alone.

Schwab: Yes, yeah.

Schwab: So what were some signs of that flourishing of the Jewish community?

Yael: Yeah. So that’s for those signs, let’s talk about specific people and their specific amazing stories because I think that’s so much more telling than saying, “Here’s something, you know, that like the Jewish community on the holding.”

Schwab: Right.

Yael: Like who’s the all-star team?

Schwab: Ooh, love it. Okay. So Maimonides is definitely on the all-star team but as I said, I want to talk less about him.

Yael: Mm-hmm.

Schwab: One person I want to talk about, very loyal listeners to the podcast will recognize this name because we mentioned him in our episode about the Khazars, a man by the name of Hasdai Ibn Shaprut.

Yael: Yes.

Schwab: Who when we talked about him in season one we said he had an amazing name. And I said, because I went back and listened to it, I said we could do a whole episode just on this guy. And we’re still not doing the whole episode.

Yael: You manifested it into being.

Schwab: Yeah. But now, now we’re giving-

Yael: Amazing.

Schwab: … Hasdai Ibn Shaprut his due.

Yael: So what, what was he about.

Schwab: Yeah. Everything. He was a polymath. He could do it all, scholar, physician, diplomat, patron of science of literature. Started out as a court physician, which was really important at that time. It’s very hard to imagine now because the White House doctor is not an important member of court, but back then it was very different.

Yael: Mm-hmm.

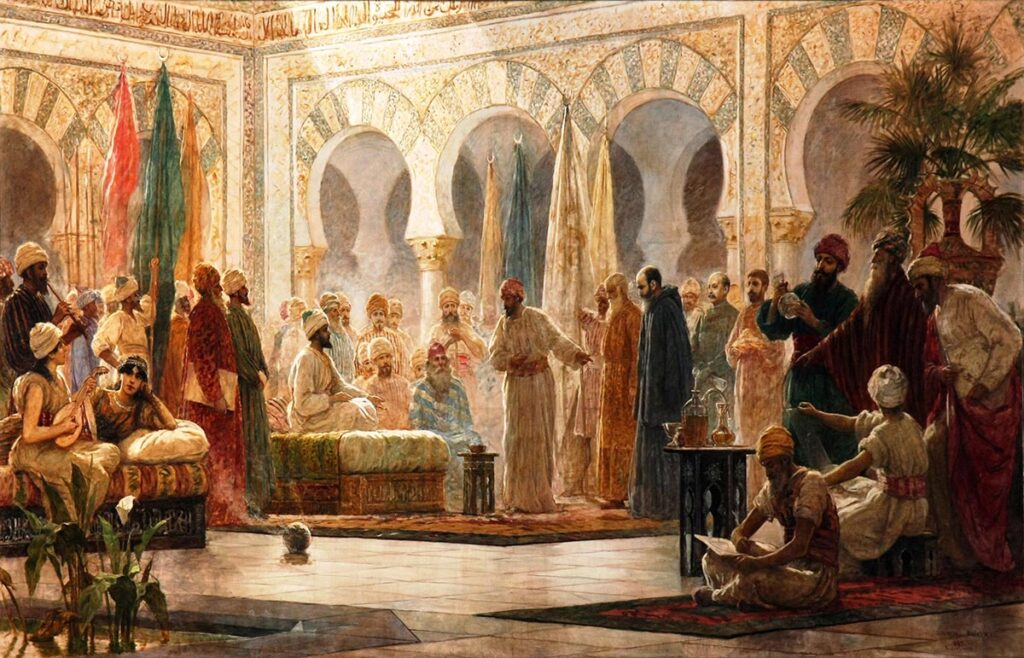

Schwab: So he starts out as court physician and through that eventually does really become the right-hand man of the Caliph of Cordoba, and basically ends up kind of running the Caliph’s foreign affairs, negotiating treaties, and doing all sorts of things. This is an incredible story. He’s able to broker a deal with a woman named Toda of Pamplona. Her family and her kingdom, Leon had been, you know, long-standing… Feud isn’t the right word. I guess like a conflict of many years, uh, between Leon and Cordoba. But crisis in Leon, this woman, Toda, her grandson, Sancho of Leon was deposed by the nobles. Side note, he was deposed in part at least because of his great obesity. They thought he could no longer adequately serve as king of Leon.

Yael: Okay. So her son was deposed.

Schwab: Her grandson. So she wants to return him to the throne and she could use the Caliph’s help and, Hasdai is able to convince her to set aside their feud and he says, “If you come to the cup and personally ask for his help, despite this long-standing feud, he will help you and can restore your grandson to the throne.” He’s saying that he knows that he can convince the Caliph to say yes to that. She comes before the Caliph, prostrates herself before him, asks for his help. The Caliph helps. Sancho is placed back on his throne.

Yael: Mm-hmm.

Schwab: And Hasdai channeling his physician doctor, medicine side is able to help King Sancho with some sort of 10th century weight loss regimen.

Yael: Wow.

Schwab: That it seems like, did work to some extent possibly.

Yael: Really interesting.

Schwab: Yeah, yeah. So he’s negotiating the treaty that puts a king back in power; that is high level stuff.

Yael: So he’s a jack of all trades.

Schwab: He is, right? But while he’s doing these political maneuvers, he’s also heavily involved in the world of Jewish scholarship. He’s sending money from Spain to the Babylonian academies at Sura and Pumbedita.

Yael: Oh, wow.

Schwab: Yeah. He’s moving scholars from Babylonia to Spain and creating new academies of Jewish learning and he’s making sure that people have access to texts and things like that. And he also sort of becomes a patron and surrounds himself with these Hebrew poets. Poetry is an extremely important art form in Muslim Spain at this time.

Yael: Mm-hmm.

Schwab: And poets are channeling that and writing Hebrew poetry, Hasdai has two poets sort of as part of his poetry salon of sorts.

Yael: Mm-hmm.

Schwab: One by the name of Menachem ben Saruk and one by the name of Dunash ben Labrat. And the two of them get into a very serious poetry feud over the-

Yael: … no one can fight like poets can fight.

Schwab: No one can fight. It seems like this fight got very serious and personal.

Yael: It’s always the artsy kids.

Schwab: Yes. I don’t think this was the basis of their fight but it was definitely a part of it was what, what place does Arabic meter have in Hebrew poetry? Like can we write Hebrew poetry? That sounds the way that the popular Arabic poetry of the time was sounding.

Yael: Age-old question.

Schwab: It is an age-old question. Dunash ben Labrat is incorporating Arabic meter and rhyme forms into his Hebrew poetry and not just Menachem Ben Saruk but a bunch of others who are saying like, “Look, I get that it’s popular and I get that people really like it, but don’t you think this is drawing us further away from our tradition and towards what the rest of the people around us are enjoying?” And isn’t there a danger to that?

Schwab: So these dueling poets are both sort of in Hasdai ibn Shaprut’s court. And the fight gets ugly and personal, and ultimately Dunash ben Labrat, the one who was incorporating the new form, accuses Ben Saruk of secretly being a Karaite, of like not following rabbinic tradition and being part of this-

Yael: Interesting.

Schwab: … group that’s considered definitely on the outs a little bit.

Yael: And undermining rabbinic Judaism.

Schwab: Yes. Right?

Yael: Fascinating.

Schwab: And Menachem ben Saruk ultimately sort of loses his position under Ibn Shaprut, and is like cast out, as everyone comes to embrace the Arabic form, and like this new type of poetry which, there were skepticism around at first, but I think that’s sort of what always happens with any art form is is there’s skepticism around it at first, but ultimately becomes incorporated in a way and used to bring greater awareness and beauty to a Jewish expression.

Yael: And that’s how the world evolves. And that’s not necessarily a bad thing, but I understand there being traditionalists and people on the cutting edge, the Nouveau poets who want to change things.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: Oh, very cool. It really sounds like there was a lot going on here.

Schwab: Yes. And let’s talk about another poet, a man by the name of Samuel ibn Naghrillah also known as Samuel ha-Nagid which means prince.

Yael: He has a street in Jerusalem, I think.

Schwab: That is correct. He has a street name for him. He’s a Talmudic scholar, grammarian, philologist, soldier, merchant, politician and serious poet in his own right. So he also can do it all.

Yael: Who isn’t it? Who isn’t it?

Schwab: Yeah. I mean, Most generals I know who are also statesmen of the highest level are also writing poetry that like the whole world is thinking carefully about. Yeah.

Yael: So they were exporting these ideas, this art that’s being created in the Jewish community is spreading.

Schwab: A lot of the poetry is in Hebrew. So the-

Yael: Uh-huh.

Schwab: … poetry is really just for us, you know.

Yael: Uh-huh.

Schwab: But there are a lot of other philosophical writings again, but like Maimonides I wish we had time to talk about you. My main man. But I want to tell you at least quickly the story of Samuel ha-Nagid, Samuel ibn Naghrillah.

Yael: Okay.

Schwab: There’s this legend that he rose to prominence because he was sort of discovered; the maidservant of the vizier asked him to write a letter and then she was so impressed with his letter writing capabilities because writing letters really well was a really important skill, so he started writing letters for her. Eventually becomes the secretary in writing letters for the vizier and then becomes an assistant to him.

But when the king dies, Samuel ibn Naghrillah positioned himself, right? And helped the younger son ascend to the throne even though the older son is the one that usually should have gotten it. And when that younger son becomes king, he makes Samuel ibn Naghrillah vizier and general of the army. Like head of the Muslim armed forces of this kingdom.

Yael: Amazing.

Schwab: Which by the way is not allowed. Like, The Pact of Umar which says what it is that Jews, or any Dhimmi are allowed to do, definitely not allowed to be general of the army, but he definitely was.

Yael: Wow, interesting.

Schwab: And he also, like Hasdai ibn Shaprut, Samuel ibn Naghrillah also is like, helps the king ascend to the throne has all sorts of political machinations on the side. There’s this story where a bunch of guys are talking about some sort of treason or something and he gets his way into this group and he says, “Let’s actually meet in my house to talk about our plan for treason.” But meanwhile he’s just like spying on them and telling the king what they’re saying.

And then the king says let’s execute them and he defends them. And like now of course everyone loves him because he’s this like brilliant guy, who’s just like, able to play all sides of a conflict somehow.

Yael: Fascinating. He was a fighter like he was actually participating.

Schwab: Oh, yeah. He’s not a general and he’s not sitting back in the bunker and like over Zoom watching with that. He leads the Army into battle. He is general of this army for 17 years.

Yael: Wow.

Schwab: Extensive military campaigns. Many, many victories. Among a lot of topics of his poetry he writes a lot of war poetry, which is considered very good war poetry. And he’s aware also I’m just like all of his different talents. He calls himself the David of his age because he’s a military leader and a poet. Um, he also writes several books. He writes this book Ben Tehillim which is sort of like in the style of and after the book of Tehillim and then later writes another one called Ben Mishlei, and then another one later called Ben Qoheleth where he’s sort of imitating the style of those Biblical books and giving his perspective at different points in life.

Yael: Fascinating. He’s a Biblical scholar. He’s a general. He’s a poet. He’s a Statesman.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: He’s a king maker.

Schwab: It’s like, imagine if Alexander Hamilton didn’t die young and like remained-

Yael: And was also an amazing rapper.

Schwab: Yeah, right. (laughs) But then like imagine if in addition to that Alexander Hamilton also wrote a book explaining the logic of the Talmud called Mevo ha-Talmud that’s frequently printed in the Talmud as like a great example of a very important rabbinic work.

Yael: So, I have to say fascinated by this.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: How did this end?

Schwab: It starts to fall apart in the 12th century when a much more conservative and oppressive Muslim dynasty begins to take over and Jews lose many of those positions. But Jews still have some opportunities even under this more heavy-handed Muslim regime, but the Reconquista, the reconquering of Spain by Christian armies which culminates in 1492 with the final surrender, to Ferdinand and Isabella who, as you know, like top anti-Semites of all time.

Yael: That’s quite a claim.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: I mean, maybe top five.

Schwab: Top five.

Yael: They’re in the conversation.

Schwab: Yes. The Golden Age definitely ends when the new Christian king and queen of Spain make it illegal to be Jewish, and kick out everybody who isn’t converting to Christianity. And then Spain goes through an age that… What’s the opposite of golden?

Yael: Tarnished.

Schwab: Hmm, I think we might need a stronger word than that, but yes.

Yael: Costume jewelry.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. What’s really interesting is at the time, nobody would say, “This is the Golden Age of Spanish Jewry.”

Yael: Right. You don’t know that until you’re out of it.

Schwab: Yeah. La Convivencia, the Spanish term for it, this like model of what a society is, that’s a term that comes up in, like, the 19th century.

Yael: Mm-hmm.

Schwab: And part of that is, as Jews are looking to be emancipated and get greater roles in their societies in Europe in the 1800s, they point to this and say, “Look, how great it was,” and are very happy to point to how amazing it was and look at this golden age of Spain when Jews were allowed. Look how much they did, not just for themselves, but look how much they contributed to society. And-

Yael: And let’s go back to that.

Schwab: And let’s go back to that. Like you will be better off if you allow all the Jews to have this place. and this notion that Jews, you know, don’t just need to be isolated but can take on all sorts of roles and can be generals and diplomats, and all of those things.

But then this whole notion is really called into question the Golden Age of Spanish Jewry and, and like how well Jews did under Muslim control when in the middle of the 20th century all of these Muslim-Arab countries expel all their Jews and there’s a series of wars between Arab countries and Israel and there’s a lot more skepticism about how well Jews and Muslims can get along. There’s What’s called the Neo-Lachrymose like the Lachrymose is like sad.

Yael: Tears.

Schwab: Yeah. Um, like this new way of looking at it actually let’s now kind of re-examine and think about how bad things were for Jews in Muslim Spain.

Yael: Interesting.

Schwab: And it feels a little bit to me at points like that’s oversell like it’s… I mean, there was definitely violence there was persecution and anti-Semitism. Jews did not have all the opportunities in the world, but a little bit it’s a reaction to the overblown notion that this was the greatest thing ever. Like no, there were definitely bad parts to it.

Yael: Well, I mean the things that survive are the things that were well-known. And, quote, unquote, “worth keeping.”

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: So the stories that persist are the stories of the successful people who served in court and wrote these books. So it certainly is very possible to me that the stories of those who were suffering did not get transmitted in the same way that these other stories are in.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: Not to add any level of (laughs) controversy to this, have you ever seen the movie, Midnight in Paris?

Schwab: A long time ago, but yes.

Yael: So, in the movie Midnight in Paris, directed by someone controversial.

Schwab: (laughs)

Yael: Owen Wilson’s character wants to live in 1920s Paris because he thinks that that is the best ever era.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: And when he’s transported to 1920s Paris, he meets a woman who doesn’t understand why he’s glamorizing that particular age. And she wants to go back another several decades herself to la belle époque.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: And he comes to realize obviously that everyone faces discontent in their own era. But that is really what I’m thinking about here in that obviously you don’t know that you’re living in the Golden Age while you’re living in it. We have rose-colored glasses when it comes to looking at the past.

Schwab: Yeah, the way we view the past always shapes the way we view the present. And the way we view the present always shapes the way we view the past. Like it’s easy to look back now. And glamorize it and I think wow, that’s so amazing that there were characters like this who were able to do both of these things that it seems so impossible to do today.

Yael: And then you remember that they didn’t have indoor plumbing.

Schwab: (laughs)

Yael: I think it is easy for us particularly in light of what you mentioned the the eviction of Jews from Muslim-led countries in the 20th century tends to blind us to the fact that for so much of our history, Jews and Muslims lived in symbiotic harmony in a lot of places in the world.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: And complemented one another really, really nicely.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

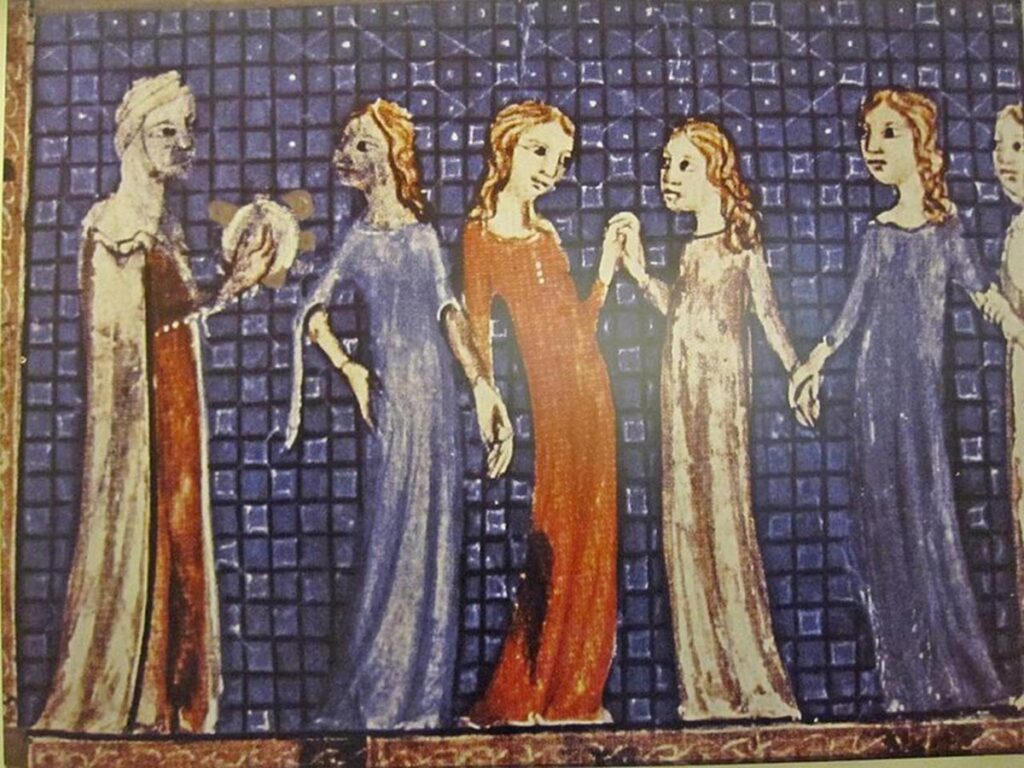

Schwab: The one other person I also wish we had time for is Qasmūna who is a female poet of great importance. Uh…

Yael: Wow.

Schwab: Yeah, yeah. Definitely.

Yael: And I’m assuming that, that women’s literacy was not at its height at this time.

Schwab: She was the female poet.

Yael: Was she married by any chance?

Schwab: Honestly, I’m not sure.

Yael: I’m just wondering if the view of the time was you could be a wife and mother. Or you could be a prolific artist.

Schwab: You could be a general, physician, grammarian, statesman and a poet but you can’t be a wife and mother and a poet, Yael, come on.

Yael: Right.