Schwab: Welcome to Jewish History Nerds, where we do exactly what it sounds like. Nerd out on awesome stories in Jewish History.

Yael: I’m Yael Steiner, and my childhood dream was to stay in school forever.

Schwab: I’m Jonathan Schwab and I am in school forever.

Yael: Schwab, what is on tap today?

Schwab: I have a great one for today. I feel like I always say that, but this is a really good one. A season and a half into this show, I think about it as, we kinda have two types of episodes. We have, here’s something you’ve never heard of, and get to learn about. Or, here’s something you’ve heard of and know about, and we’re gonna tell you a deeper story.

Yael: I like that. I totally agree.

Schwab: Yeah. Today’s episode is kinda both, because part of it is, we’re gonna talk about a woman I feel pretty confident you never heard of, I had never heard of. But, the sort of larger surrounding story is something you and many of our listeners probably have heard of, and I had heard of also, and really enjoyed doing a deep dive, to learn more about this.

Yael: Okay. You have captured my attention.

Schwab: Great. So we’re gonna talk about a woman named Wuhsha the Broker.

Yael: Wuhsha.

Schwab: We’ll get into this, but it’s Wooch-sha, but it’s a much lighter “ch.”

Yael: Woo-ch-

Schwab: I will try this once (Laughs) And then we’ll probably just call her Wuhsha for the remainder, but…

Yael: (Laughs) okay.

Schwab: I think it’s Wuhsha.

Yael: Okay.

Schwab: The Broker. Which isn’t even a real name. Woo-Cha itself is a nickname, that means, like, beloved. It shows how well-liked she is, and shows what her job is.

Yael: What is she brokering?

Schwab: She’s brokering so much. She’s brokering a lot. And this was not the intention of the name, but one of the things that she’s brokering and negotiating, and, and really figuring out is her place in the Jewish community, because it was not so simple.

Yael: When did Wuhsha live?

Schwab: End of the 11th century, early 12th century in Cairo, Egypt. Among the many other details, she’s very remarkable for her brokering and her wealth and her business acumen, which is especially interesting because she’s a woman.

Yael: And we’re notably bad at business.

Schwab: (Laughs) She was quite good at business. (Laughs) Cuts against, maybe a sexist expectation. For you of all people to have.

Yael: I know, seriously.

Schwab: But, in addition to her business, what was remarkable about her is some details of her life, and especially that she has a child out of wedlock, and does a lot of negotiating and working to get this child not just accepted and, on the record, noted as the son of his father, but accepted in the community in a way that clearly was very difficult for her, and for her son.

Yael: I’m assuming that was a massive achievement at the time. Because even today that could be extremely difficult.

Schwab: Yeah, a child born out of wedlock being accepted in the Jewish community, not so simple. Definitely not so simple in 11th, 12th century Jewish Cairo. But it seems like she does manage to achieve this. And this is a callback to a story that has a lot of similarities in Season One, Babatha. This is not a person that, like, was known to us for many hundreds of years. Everything we know about her is through the study of history in the last couple decades. And specifically, the study of a trove of documents that tells us a lot about how Jews were living at the time. Commonly called now the Cairo Geniza.

Yael: I have heard of the Cairo Geniza. I am, I don’t want to say ashamed. But a little bashful to say that I don’t know too much about it. I believe it’s probably the largest trove of Jewish documents in the history of the world, maybe.

Schwab: Yeah, it might be, depending, on what type of documents you’re thinking. I think it might be the largest trove of any documents, that we have. And that’s due to a couple of interesting circumstances. So let’s talk about what the Geniza is, because, similar to you, before I started the research for this episode I probably knew the basics of the story and knew that it was really important. It’s a really incredible story.

Yael: My understanding of a Geniza in general is a storage place, possibly underground.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: Of documents that contained God’s Holy Name on it, that are not supposed to be disposed of in the ordinary course. Like, we don’t throw holy books in the garbage, we bury them, in what is known as a Geniza.

Schwab: Yes. Pretty spot-on, so far. There actually is also this ancient second sort of Geniza. Many of the texts often went to the same place, but in addition to the holy things that we didn’t want to dispose of, just by sort of throwing them in the trash, it also acted sometimes as a sort of censorship. You know, here’s a book that is possibly dangerous, or could be provocative in a certain sort of way, and we might also put a text like that into a Geniza. We don’t do that nowadays, but you’re right that we have in modern times still maintained the practice of, there are certain types of holy books and scriptures that we do not simply throw away. And then these things will be buried like we bury a human body, or very often even with a human body.

Yael: Yeah, I’ve seen that at funerals.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: Right, there’s like a cardboard box outside the sanctuary in your synagogue to leave things in. And then, there’s a funeral and someone brings the box and it goes in the ground.

Schwab: Right. And the word that’s often used for things like that nowadays is shaimos, names, because very frequently the way it’s determined is does it have the written name of God on it? That is where the line is often drawn. Certainly in Orthodox Judaism. If you’re printing something out, some people are very careful to make sure not to print the actual name of God, but some sort of substitution. So that these papers can be disposed of in a regular way and don’t have to wind up, you know, there.

But, there are different traditions for what needs to be handled this way. And weirdly we don’t understand exactly why the Jewish community in old Cairo, which was also called Fostat, got this idea that everything that had any Hebrew writing on it needed to go to the Geniza. Needed to be saved so that it could be buried in this way. And they had a room in their synagogue where they put documents like this. Unclear if the intention was that they would be buried or at some point it just became this is the permanent place for it, this room in the synagogue and we just throw all of our paper there. And that’s what it really became. They threw all their paper there that had any Hebrew writing on it whatsoever.

Yael: I’ve always pictured the Cairo Geniza as a pyramid. And I know that that’s wrong. But I always just thought of it as this pyramid that Indiana Jones would go into. And instead of finding, like, jewels and all sorts of weird statues it would just be cardboard boxes filled with source sheets. From, like, a lecture that somebody gave (Laughs).

Schwab: So let me correct that image based on the descriptions of people who have explored it. It’s not a particularly large room, actually. It’s probably around the size of a typical bedroom, or, you know, a little bit smaller. Things were certainly not in cardboard boxes. (Laughs)

Yael: (Laughs)

Schwab: it’s literally stuffed floor to ceiling with just paper. And very dusty and the only way you could see it is by accessing it through a secret cha-… And like, as I was imagining it, harkens back to my childhood. Scrooge McDuck, you know, has, like the vault of gold coins…

Yael: Yes.

Schwab: And he can literally dive into it. And it’s like that. you could literally dive into just full of paper. You should not, you’ll probably ruin some of the manuscripts if you did that.

Yael: Also, paper cuts.

Schwab: Yeah. (Laughs) This is not high-quality printer paper, all the edges have probably been worn down.

Yael: Right, I was gonna ask, is it papyrus? Or is it paper?

Schwab: It’s everything. Paper, papyrus, vellum, other words that I’ve never even seen (Laughs) before.

Yael: Vellum?

Schwab: All sorts of materials, all sorts of ink from every type of thing, right? Like it’s everything from holy books to grocery receipts, to letters, to things that weren’t any, even in Hebrew that got mixed in there. There’s a document in the Geniza that’s in Chinese.

Yael: Wow.

Schwab: Like, how did that wind up there? So really, all sorts of different stuff. Just piled, ’cause it was just thrown in haphazardly for centuries. It’s not organized in any way whatsoever.

Yael: When did we find this?

Schwab: Great question. So the synagogue’s called the Ben Ezra Synagogue, was in operation continuously, and actually it seems like some things were still being added to it up until the 19th century.

Yael: Wow.

Schwab: There are documents in there that are more recent. Although the vast majority of it is much earlier, from the 800s to the 1300s. So the Jews who used that synagogue always knew that it was there. There were a lot of superstitions around it. When people came to see it sometimes they would be told there are all sorts of curses on it. If you go in there you could be cursed to die within a year. There’s a serpent that guards it.

Yael: It’s very Indiana Jones.

Schwab: It is very Indiana Jones.

Yael: Do you think that Steven Spielberg could be persuaded to make a sixth Indiana Jones, “Indiana Jones and the Cairo Geniza?”

Schwab: Indiana Jones and the Cairo Geniza. And the movie will go as follows: It’s about 45 minutes of maybe he has to defeat this serpent, which didn’t exist. Defeat the serpent and get the documents, and then the remaining hour and a half of the movie is him sorting through fragments of these documents, trying to figure out which way is right side up. Trying to understand why there’s writing on the back in a different language…

Yael: Sounds like a hit.

Schwab: Indiana Jones and Archival Document Work. (Laughs) And that’s true, by the way. Things being written on the back of the paper in a different language or something. Because very often paper was just reused. So somebody might have their, I don’t know, local bill in Arabic, about their rent or something. And then they’d write down whatever it is they were writing down, you know, practiced their alef-bet on the front of it, and then because it has Hebrew writing on it, it’s gotta go into the Geniza. And that winds up there. And if we can understand it, this is so fascinating ’cause now, here we have two things in one. And example of rents in Cairo in the 11th century, and what it looked like when people practiced the alef-bet.

Yael: That’s very cool.

Schwab: Yeah. So in the late 1800s, historians begin to think about looking at this, exploring it, understanding what’s in it. There’s one early historian who gets to explore it a little bit, take some of the documents, but it comes to the attention, a couple years later in 1890s, of these Scottish twin sisters, Protestants, not Jews, who were very interested in history and specifically in Egypt. Had gone to Egypt a number of times and they acquire some documents, some series of documents that had been from the Geniza.

They’re very fascinating characters themselves, these twin Scottish women. They were both married. Both their husbands die. One of their names is Gibson and one of their names is Lewis. And they come to be know collectively as the Giblews. Like, “Oh, party at the Giblews tonight.” But all these parties obviously are, you know, historical document parties. As the best parties are.

Yael: But what you’re saying is they’re both romantic interests potentially for Indiana.

Schwab: (Laughs) Oh, yeah, yeah.

Yael: Okay.

Schwab: I don’t know if they were identical, but in this Indiana Jones movie, maybe there’s like, an identity confusion thing going on.

Yael: Oh, interesting.

Schwab: Steven Spielberg, we know that you’re listening to the podcast. Call us, we have an amazing pitch for you.

Yael: Okay, so these two Scottish sisters come…

Schwab: They have a document and they share it with their Jewish friend, a man by the name of Solomon Schechter.

Yael: I have heard of him.

Schwab: That Solomon Schechter. The name that the Conservative day school network is named after, that, you know, same guy. And for reference, a lot of what I am working off of is a book called, “Sacred Trash.” Which is all about the Cairo Geniza. Great title, great book. It has amazing descriptions of all the characters involved, amazing descriptions of Gibson and Lewis, and of Solomon Schechter, who the authors of this book, Adina Hoffman and Peter Cole, love Solomon Schechter. Their descriptions of him are amazing.

The Scottish twins share some of these documents with Solomon Schechter, and he says, “I have to look at this more. I think there’s something really interesting here.” Takes one of these documents home, and, you gotta like, read the original telegraph he sends them. But he sorta telegraphs them immediately and says, “We have discovered something of monumental importance. Please come to my house immediately. We must discuss. There is something that is like the greatest treasure ever found here.”

Yael: So what was on this document.

Schwab: They see that this document that they found is the original Hebrew of a book called, Ben Sira or Sirach or referred to in Christian bibles as Ecclesiasticus. We’re going off on a slight tangent here, but it’s a very fascinating part of biblical studies, this is a book that almost made it into the bible.

Yael: Oh, wow.

Schwab: It is included in many Christian versions of the bible. Solomon Schechter knew about this book, and, and everybody had known about it, and knew there was some original Hebrew version of this book. But the only surviving text we had was a translation written by the author’s grandson a couple of generations later. And that translation survived. So we had the Greek version, but in 1897 nobody had for hundreds of years seen the Hebrew version of this book that, again, almost made it into the bible. And is, and is quoted in the Talmud, like clearly…

Yael: Wow.

Schwab: Is an important text in Jewish history that is lost. And then all of the sudden Solomon Schechter is looking at a page of it in his…

Yael: That’s amazing.

Schwab: I think his living room. You know, like he was just looking at it, and he’s like, “Oh, my God, this is an original page of the Hebrew of this book.”

Yael: So how do they go about sifting through all of the papers in the Geniza to find the rest of it?

Schwab: So, not so simple. Uh, and in fact…

Yael: I would imagine.

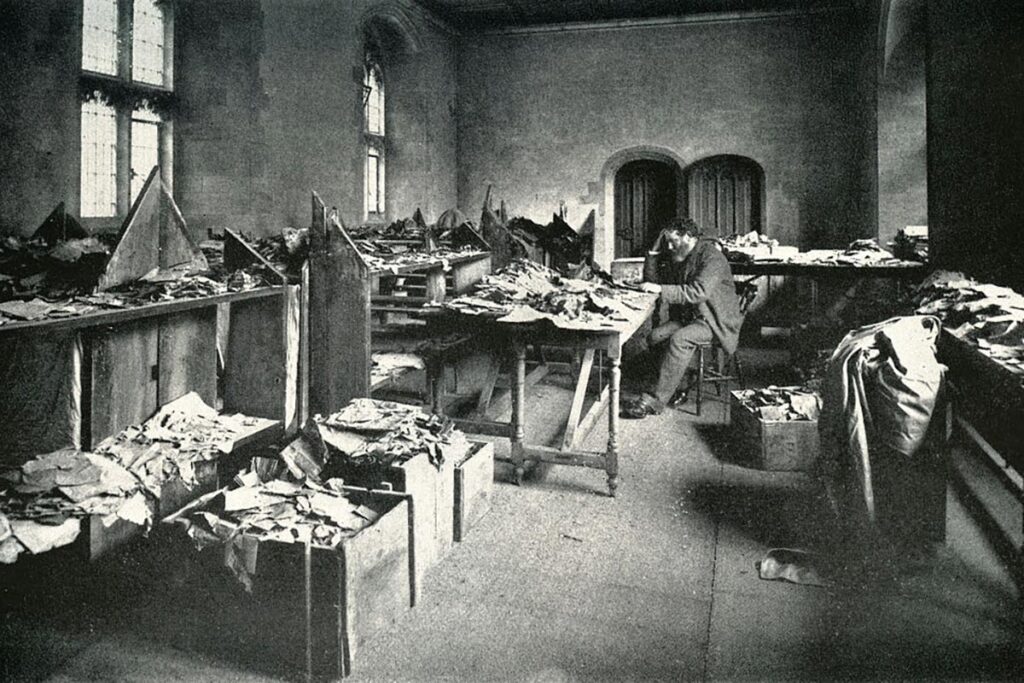

Schwab: Work they’re not entirely finished with yet. (Laughs) Because it’s tremendous. It’s, like, think of, the largest volume of papers and texts you’ve ever seen in your life, it’s more than that. So, we haven’t come close to getting through all of it. But, he realizes the importance of it and sets about raising money, saying, “We need to get to the Geniza and we need to uncover everything that’s there.” Because in addition to, you know, recovering this book, here is a view of history we’re never gonna have the chance again at. Which is true. Like, through this amazing series of coincidences. Through the fact that this community kept this very odd habit of storing everything. Through the fact that the climate lent itself to preserving things pretty well.

Yael: Oh, wow.

Schwab: Again, these things are not preserved perfectly. But, because it was relatively dry, because this room was left untouched for hundreds of years, things are preserved pretty decently.

So, they mount this expedition. And I know we’re gonna get some comments on this. There are people who claim Solomon Schechter was not the one who discovered it. One of the earlier explorers, I think a guy named Newbauer, it could be Doctor, I’m not sure. Or Rabbi, there were people who earlier understood the importance, but definitely Solomon Schechter is the one who sort of does the work of getting this expedition going. Um, they pack up a ton of these manuscripts and are shipping them back to England. That ship almost sinks. Which, crazy, right? Like, can you imagine?

Yael: Wow.

Schwab: But, thankfully the ship did not sink, makes it back to England. These manuscripts end up being distributed through a lot of different libraries in the world. There’s a bunch of them in libraries in England. There’s a whole bunch of them at Penn, University of Pennsylvania. And there are so many of these documents we are nowhere close to fully cataloging and understanding everything that’s in them. But as historians start going through that, which is work that takes decades. This is from the 1890s when it’s first being collected to today in 2023, historians are still understanding a lot of what’s written and kept and stored there. And what it tells us.

Uh, but, now I want to come back to the very narrow part of our focus for today. Which is this woman named Wuhsha, who we learn about from some documents kept in the Geniza. She’s not a major player on the world stage or anything like that, but, we have a couple of documents that a historian named Shlomo Dov Goitein.

Yael: Uh-huh.

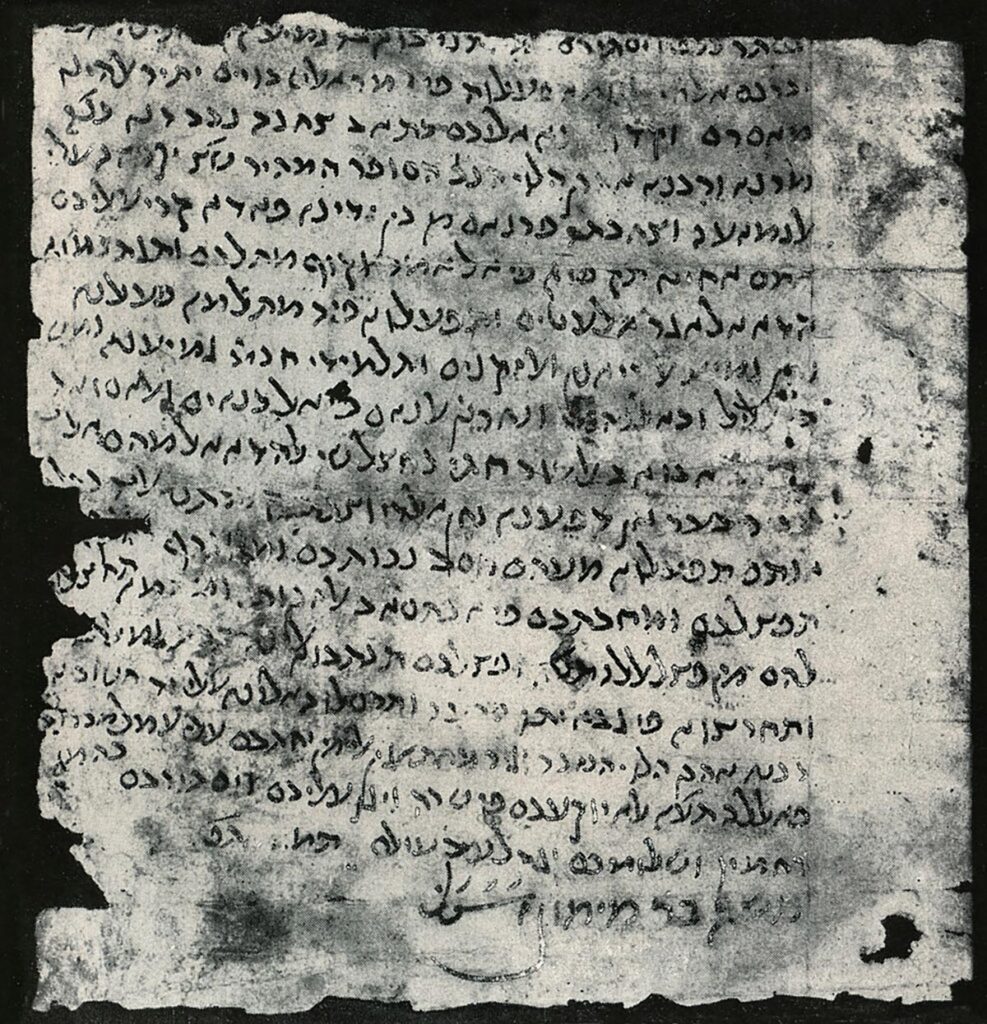

Schwab: He unpacks this history, and publishes her story. Wuhsha al-Dallala, al-Dallala means the Broker. Wuhsha the Broker. A lot of what we know about is from a couple of different documents. The most important document is her will, first, it demonstrates the wealth that she had. This is all in terms of dinar, which is the currency of the time.

Yael: Uh-huh.

Schwab: we know from a lot of other documents that a dinar is two weeks pay for middle class.

Yael: Mm-hmm.

Schwab: Depending on what you consider middle class, but like in 2023 American dollars, a dinar is certainly a few thousand dollars, maybe a little more than that.

Yael: Uh-huh.

Schwab: So we know from her will, just… she lists at least 600-something dinar that are supposed to be distributed in different ways. So we’re talking about, translating to today’s dollars we’re talking about at least a million dollars probably. Maybe much more than that. Hard, hard to tell for certain. But, like, this is a very wealthy woman.

Yael: Mm-hmm.

Schwab: Who is not married. And who, where she leaves her money to is very fascinating because a ton of it is left to charity.

Yael: Good for her.

Schwab: Yeah, good for her. We can sort of speculate why that might be a little bit. But part of it, I think we can definitely conclude, like, she was a woman of great wealth, but saw the purpose of a part of that wealth was to give back to her community. The other major thing that she clearly really cared about and wanted to leave money to was to her son. And this is the part that gets, I think really fascinating.

She has a son, who’s referred to as Abu Saad.

Yael: Mm-hmm.

Schwab: And she wants to leave a lot of her money to him. Wants to leave money to him to make sure that he is educated. And lived comfortable. But also very much wants to be clear how he should be accepted in the community, because as I mentioned at the top, this was a child who was born to her out of wedlock, with a lover, Hasoon, of Askelon, or Ashkelon.

And she wants to make very clear this is a… First of all, my son, Jewish kid, his father is Jewish, this is who his father is. So that, so that her son could be fully accepted, fully able to marry other Jews. That he’s not an outcome of an incestuous, or any sort of problematic relationship. Although, he’s born out of wedlock, through… It’s kind of, you know, problematic. In some ways.

Yael: Right, but not one of the Torah prohibiting relationships.

Schwab: Right. Yeah.

Yael: That would cause a child to be cast out of Jewish society.

Schwab: Exactly, she wants to make sure that he is not cast out in any way. This is clearly a priority for her. She does not leave a lot of money to the boy’s father, to this guy Hasoon. Perhaps she was, I don’t know, jilted by him in some.

Yael: I could think of a lot of reasons.

Schwab: Yeah, from the will it doesn’t seem like she feels particularly fondly…

Yael: But she leaves him something, you’re saying?

Schwab: She, one of the things that she leaves him, um, is two promissory notes concerning the debt of 80 dinars which he owes me shall be handed to him. So like, his debt to Wuhsha of 80 dinar…

Yael: It’s a lot of money.

Schwab: Yeah, is forgiven. So, like, this dude owed her a lot of money.

Yael: Okay, that’s something.

Schwab: Yeah, mm-hmm. And that’s also, like her business is loaning people money, and, and taking collateral. And maybe even, selling these loans to other people, that’s what she was brokering.

Yael: Oh, she was the first mortgage-backed securities broker.

Schwab: Yes, yeah. And she got pretty wealthy it seems like, off of that business.

Yael: The backs of the poor. (Laughs)

Schwab: I don’t know if it was the poor, or everyone. But, yeah. We don’t know for sure. But she definitely-

Yael: Okay.

Schwab: And again, if she got wealthy off of poor people, she certainly was giving it back to them. Also listed in her will to the poor of Old Cairo 20 dinars, to the cemetery 25 dinars, to the synagogues 20 dinar. Like, she was leaving a lot of money to care for a lot of people.

She also, a lot of money was set aside for her funeral. And scholars sort of assume that part of that was here is a woman who was not totally accepted in the community during her time, and planning a very elaborate and expensive funeral, uh, was a way to make sure that she was recognized at least in her death as not just a member of the community but an upstanding and important member of the community.

Yael: Interesting.

Schwab: Yeah. The way Goitein describes is, the funeral expenses based on other documents we had from the time, exorbitant.

Yael: I’m picturing, like, Aretha Franklin’s funeral. With, like, the pink Cadillacs driving through Detroit. Because all she wanted was a little R-E-S-P-E-C-T, it seems like.

Schwab: It’s not wrong to picture that, because, again in this will document, one of the things that she details is, the remainder of 50 dinars shall be distributed to the cantors who will walk behind my coffin to each according to his rank and excellence.

Yael: Amazing. She was very concerned about her legacy, it seems like.

Schwab: Yes, definitely very concerned about her legacy. I wanna also tell the story of another document that we have. (Laughs) Because it tells us a lot about, this thing of her son and her lover. And it’s a really fascinating one. This guy Hasoon is from Ashkelon. We assume that that means he was some sort of refugee from that land.

Yael: Uh-huh.

Schwab: Possibly he had another family there, maybe that was why he and Wuhsha were not able to marry. But we had a document recorded when she comes to the court seeking the advice of a good friend of hers. Her confidante who she often went to for solutions about things. So, Wuhsha comes to the court and says, “What advice do you have for me? I had an affair with this guy, Hasoon. We are expecting a child. We also were legally married in a Muslim court,” Which is a huge no-no. That’s not looked favorably upon by the Jewish court. “Um, but I’m worried that Hasoon is going to deny paternity of this child and people will question where this child has come from.” Which also, we can speculate, the fact that people would question it leads us to believe that this is a person about which people know or might assume that she could have had a child with other people, I guess, let’s put it that way.

Yael: Uh-huh. Understood.

Schwab: So she wants to establish very clearly, that she’s in a relationship with Hasoon. And the advice that she’s given, this is a such a strange story (Laughs). The advice that she’s given by her confidante guy that’s written down in this court record is, get a couple of people together who are reliable upstanding people who can be witnesses, and tell them to come to your house and surprise you.

Yael: Oh my gosh.

Schwab: They’ll come in and they’ll see you with Hasoon and then they will be able to testify that, yeah, they’re definitely together because we walked into their house and saw them together. So she plots this. She knew they were coming, Hasoon did not. Um, and everything goes sort of, as planned. These witnesses see her together with Hasoon, and then she gives birth to a son later and the witnesses say, “Yeah, we know she was with Hasoon, because we saw them together in her apartment on the upper floor of this building. And therefore we all can testify that this son who was born is Hassun’s son.

Yael: This is like an episode of Maury.

Schwab: (Laughs) Yeah…Hasoon, you are the father. And, again, she’s concerned not that just other people will think this but that Hasoon himself will deny the paternity of this child.

Yael: So she sets this up.

Schwab: She sets this up, she’s able to make it happen. Again, it just reminds me in a lot of ways of Babatha, like, here’s a woman who gets how to use the system and is able to use the system to get the things that she wants.

Yael: Really interesting.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Another really fascinating part in that same court record is it’s being written by this person who works in the court, and he says, another story that’s interesting about Wuhsha is that she went to the Synagogue of the Iraqis. Like the Jews from Iraq who had moved to Cairo.

Yael: Uh-huh.

Schwab: On Yom Kippur. On the holiest day of the year. And the head of the synagogue there saw her and made her leave the synagogue. We assume because of her reputation. Uh, the fact that it’s being written together with part of this story makes it seem that way, certainly.

Yael: Like she was a harlot.

Schwab: Yeah, not acting in line with the mores of the community to the extent that she was kicked out of the synagogue on Yom Kippur, on the Day of Atonement, which is like…

Yael: You’re not even gonna let her atone? You think she’s such a bad person.

Schwab: Kicking somebody out of synagogue on Yom Kippur, you’ve gotta really think that that person is well outside the bounds of the community. And I don’t know how to interpret this, and I don’t know what it means, whether we look at it as, like, another act of chutzpah or whether this is her being incredibly generous of spirit, or, was there some sort of reconciliation we don’t know about. But, in her will she left a lot of money to a lot of different places, including specifically this synagogue, the Synagogue of the Iraqis, I’m leaving money to that synagogue.

Yael: Wow. That’s a real power move.

Schwab: It is, that’s why she’s Wuhsha the Broker.

Yael: The Broker.

Schwab: She’s the originally Power Broker. Yeah.

Yael: Take that, Robert Caro.

Schwab: (Laughs) And we wouldn’t know about any of this if not for the Geniza, if not for these documents being kept, and then uncovered, and then analyzed and looked at. And when I think about the study of history I’m just like, the Geniza had this, this book that almost made it into the bible and that’s one way of looking at history, it’s just like, what are the major texts and who are the major players? And then there’s also characters like Wuhsha and what that tells us. First of all which is, what an interesting person. You know, Steven Spielberg, we could also make a Wuhsha movie.

Yael: Uh-huh.

Schwab: Spielberg probably not the right director for that one.

Yael: He’s the right director for everything.

Schwab: We’ll think more about it. (Laughs) But also that tells us so much. You would have one view of history if you just read the legal codes and the things that are put out by rabbis and leaders of the community. But, here is a person who is operating on the margins, and doing kinda her own thing. And she, too, is obviously a really important member of the community her own way. And tells us a lot about what it means to be Jewish, and to be in a Jewish community.

Yael: And what’s really interesting about this to me, is that all of this information was retained almost by accident. It was retained because it had Hebrew writing on it, but it wasn’t retained because anyone felt specifically that it had historical value.

Schwab: Right.

Yael: It reminds me somewhat of the Oneg Shabbos archives that we talked about in Warsaw Ghetto last season. But completely at the opposite end of the spectrum. Those were documents that were deliberately collected by a historian who wanted to make sure that what happened in the ghetto was preserved. These are documents that preserved what life was like in Cairo at that time, but they were not sought out. They were hoarded.

Schwab: Right, they were preserved for history, a comparison is often drawn to the Dead Sea Scrolls, but those are documents that were preserved because they were really important. These are documents that were not important and were not intended to be history.

Yael: Right, they would have gone in the garbage, but for this religious prescription.

Schwab: Yeah, and there’s something really interesting just thinking about these documents were supposed to be buried. You know, and, opening up the Geniza and reading them, we’re exhuming it, right?

Yael: It’s raising the dead.

Schwab: It really is raising the dead. Like, and now here we’re bringing this character Wuhsha back to life, through reading it. But that was not the intention of, of putting the documents there in the first place.

Yael: Can you go to the Cairo Geniza? Like, can I fly to Cairo and go there?

Schwab: See, I think all the manuscripts have been taken out, like with many great historical sites in the world. Like I said, this is just a simply massive trove of text, you can go online, we’ll put the link in the show notes to this crowdsourced Scribes of Geniza project, where a lot of these things that have been digitized but have not yet actually been, been looked at or analyzed. And any person can go and look at it and help scholars determine just, because the scholars don’t have time to go through everything. So, like, this needs to be right side up. This seems to be in Hebrew, if you can translate some of it, translate some of it, highlight which things deserve more immediate analysis, more immediate focus, it’s such a cool project. I have spent some of my time just like, flipping through various fragments of, and pieces of documents there.

Yael: Sounds awesome.

Schwab: Oh, yeah, you know, “this does not look important” is the answer for most of them. (Laughs) But like, needs to be rotated, this does seem to be Hebrew, this doesn’t seem to be Hebrew.

Yael: If only we had, uh, Wuhsha the Broker here to endow a foundation to…

Schwab: That’s what she should have left her money to. (Laughs)

Yael: (Laughs) Let’s get some, uh, full-time researchers.

Schwab: And if it had been invested, you know for, for the last 800 years. Imagine how much money we’d be talking about, now.

Yael: Yeah.

Schwab: Yeah. (Laughs)

Yael: I mean, it sounds like there are a lot of people out there who are invested in this.

Schwab: Yes, yeah, yeah, yeah. There is.

Yael: Very cool. There’s so much good stuff out there. And I mean that, when I say that they’re amazing topics and stories for us to discuss on this podcast. But I also mean it in a, a much more literal by in that, like these documents are out there. Like there’s just a room in a synagogue somewhere in Cairo.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: With all these documents. And for all we know there are dozens more out there in the world that just haven’t been discovered yet.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: Probably not, but you never know.

Schwab: I hope so. I feel like, you know, for all these discoveries that we’ve talked about, you know, like the discovery of Babatha’s documents, and the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Oneg Shabbos archive from the Warsaw Ghetto, and the Cairo Geniza, like, is there something else that we haven’t even found yet, that in our own lifetimes someone’s gonna discover. Or, will it be discovered and we won’t even appreciate its value until years later because people knew about the Cairo Geniza for a while until they fully understood the importance.

Yael: And this is why I haven’t thrown out my 10th grade math notes yet. Because one day someone might need to read them to discover something important about the world.

Schwab: Or about you.

Yael: The closet in my childhood bedroom is going to be (Laughs) where they are found.

Schwab: It’s so funny that you’re saying this and laughing about it. I have literally the exact same thing. I have a cardboard box in my parent’s house, um, where I saved a lot of mostly school documents. Um, and labeled them by year. And my parents at one point said, like, “What is the point of this?” And I, the box was labeled, um, Yonatan… My parents call me by my Hebrew name, Yonatan, it’s on school stuff. And then later, uh, a couple of years ago at some point in my 20s I crossed that out and wrote “For the Biographer of Jonathan Schwab.”

Yael: (Laughs)

Schwab: And you know what? That person will thank me.

Yael: But they won’t pay you.

Schwab: No, no I don’t think so. (Laughs)

Yael: Good for you. I appreciate that level of self-confidence.