Chances are, if you live in North America, your experience of Judaism has been pretty Ashkenazi, or “European.” After all, 66% of American Jews identify as Ashkenazi. But despite the cultural traditions built in the diaspora, Jews are indigenous to the Middle East. In fact, the term “Jew” comes from Judea, or Yehuda — the Iron Age kingdom whose artifacts lie just beneath the surface of modern-day Israel.

Early Jewish history in the Middle East

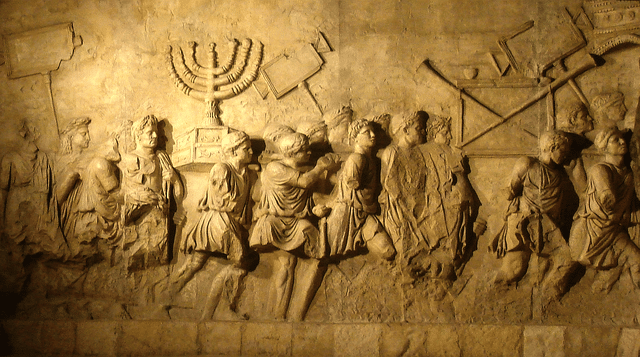

In the second century C.E., Roman occupiers crushed the last hint of Jewish rebellion in the region. The subsequent Jewish exile lasted nearly two thousand years, creating a far-flung Jewish diaspora.

The Jews who made their way to Southwest Asia and North Africa became known as Mizrahim (“Easterners”). For centuries, these Middle Eastern and North African Jews lived and worked, prospered or suffered, as guests in foreign countries, their fortunes linked to the whims of often-unfriendly rulers.

Nazis in the Middle East

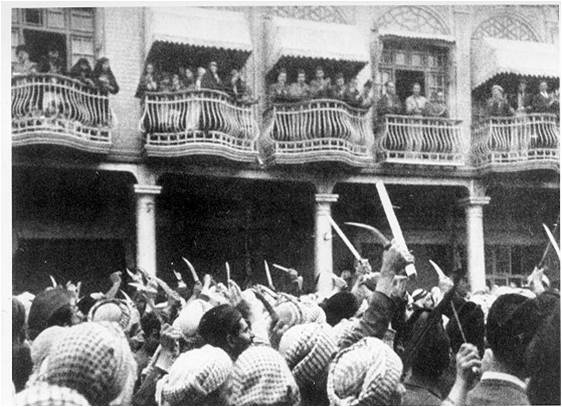

Like Jews around the world, Mizrahi Jews dreamed of returning to their ancestral homeland, directing their daily prayers toward Jerusalem. This dream became an urgent necessity as the Second World War inched closer to their borders. By 1941, the Nazi ideology that had consumed Europe made its way to the Middle East. Violently.

After a failed coup attempt, Iraqi fascists took their displeasure out on the country’s Jews, murdering, maiming, raping, and looting in a rampage of violence known as the “Farhud” — Arabic for “violent dispossession.” Under the collaborationist Vichy government, North African Jews were stripped of their citizenship. Thousands were then deported to forced-labor camps, where they were horribly abused.

In “grave danger”

By 1945, Europe was a smoldering ruin, with its Jewish communities hollowed out. As shell-shocked refugees trickled into Palestine, the UN prepared to vote on a plan that would carve out two separate states, one for Jews and one for Arabs, from the tiny sliver of land between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea. In response, Muslim countries from Egypt to Iraq vowed that if Israel came into existence, the region’s Jews would suffer horribly.

A New York Times headline from May 1948 summarized the situation aptly: “Jews in Grave Danger in all Muslim Lands: Nine Hundred Thousand in Africa and Asia face wrath of their foes.”

But Mizrahi Jews had a safe haven. True, their destination was a tiny, desperately poor country embroiled in a war against six much larger nations. And yes, it was bursting at the seams with refugees and survivors from all over the world. But it was also a place toward which Jews had directed two thousand years’ worth of prayers. And it was – and remains – the only country in the world that provides Jews with refuge, no questions asked.

All told, nearly 600,000 Mizrahi Jews streamed into Israel between 1948 and 1972. Most were destitute, their property seized by the governments of their former homes. The total value of the assets stolen from Mizrahi Jews by Muslim governments is estimated to be worth $6.7 billion in today’s dollars.

But Mizrahi Jews who emigrated to Israel brought with them a different kind of wealth: that of a rich culture. They spoke Arabic, marked auspicious occasions with henna ceremonies, and read the Torah with lilting inflections. Uncomfortably for the Ashkenazi establishment, Mizrahi Jews bore a deep cultural resemblance to the country’s highly unfriendly neighbors. Plus, many of the die-hard secularists in the government disdained the piety of the recent immigrants, who clung tenaciously to their religious traditions.

Living in Israel

As you might imagine, the transition to Israeli life was rocky at first.

Millions of immigrants from all over the world stretched the state’s meager resources. There wasn’t enough money or room to house them all, so the new Israeli government created temporary transit camps made of corrugated tin called ma’abarot. Numerous government leaders described the ma’abarot’s conditions as “catastrophic.” Though they were not built solely to house Mizrahim, 58% of the Jews who came from Arab lands before 1951 were sent to these overcrowded shantytowns, compared with 18% of those who came from Europe.

The discrimination continued as the state matured. But so did Mizrahi resistance. Riots in 1959 eventually inspired a movement known as the Black Panthers, modeled after the American civil rights group of the same name.

Slowly, Mizrahi figures became much more mainstream, strongly influencing Israeli culture. World-famous Yemenite-born singer Ofra Haza led Israel to a second-place victory at Eurovision in 1983. A year later, Iraqi-born Rabbi Ovadia Yosef — a hero to Israelis of all backgrounds — established a major political party called Shas to represent Mizrahi interests.

Today, Mizrahi culture is almost synonymous with Israel. Turn on the radio, and you’ll likely hear the silsulim and maawalim of traditional Mizrahi music transposed onto modern pop. Ask any Israeli about an iconic Israeli food, and they’ll tell you mlawach, not matza balls. You’d be hard-pressed to find a Jewish Israeli of any background who hasn’t attended a mimouna or a henna. Most notably, as of 2016, 20% of Israelis are half-Ashkenazi and half-Mizrahi.

The country’s European founders might not have imagined their country with over 50% Mizrahi. They may not have predicted Mizrahi politicians in the Knesset, mixed-ethnicity families in every other house, or Mizrahi entertainers at the top of the charts.

But in the words of writer Matti Friedman: “That we are free, safe from persecution, and in charge of ourselves—these things are new. But that we are here [in the Middle East]? There is nothing new about that at all.”