Schwab: Welcome to Jewish History Unpacked, where we do exactly what it sounds like, unpack awesome stories in Jewish History.

Yael: I’m Yael Steiner, and my childhood dream was to stay in school forever.

Schwab: I’m Jonathan Schwab, and I am in school forever. Yael, I’m really excited to hear what you have.

Yael: I’m glad you’re excited because today we’re gonna be talking about a person who I had never heard of prior to starting to work on this podcast and I think is one of the more interesting people in Jewish history, and I’m kind of astounded that he never came up in my formal education.

Schwab: Great. I’m glad we’ll all learn now.

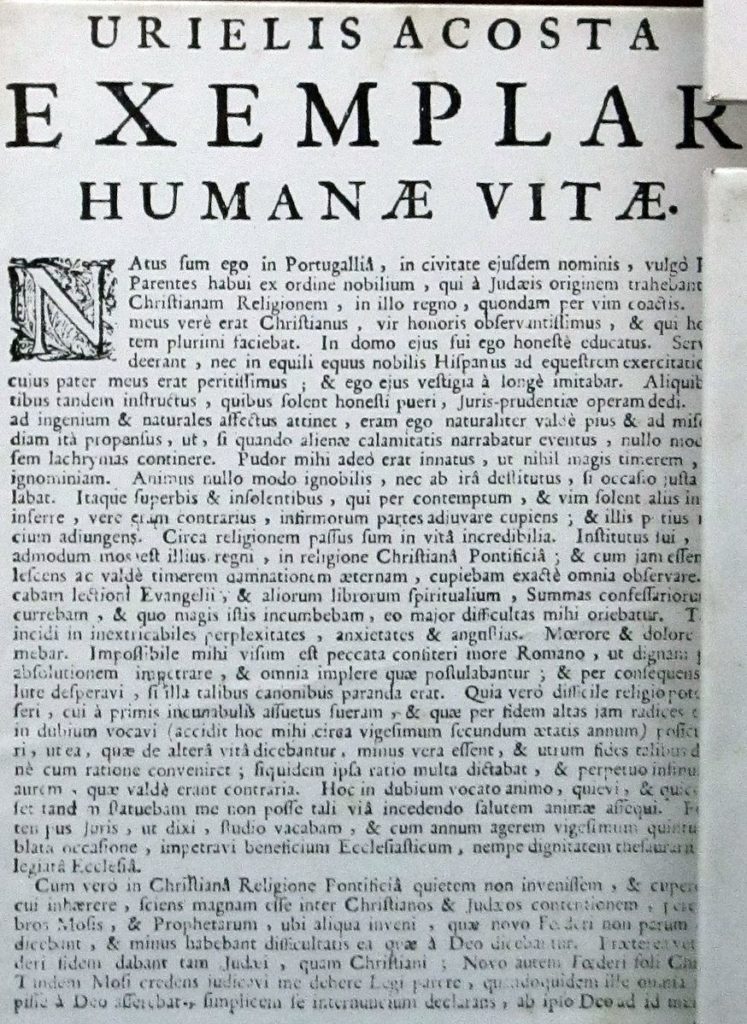

Yael: His name is Uriel D’Acosta, or that was the name he used towards the end of his life. And he was a Portuguese native who ended up living in a bunch of different places including Hamburg and Amsterdam. And ultimately was someone who was excommunicated by the Jewish community three times in his short life.

Schwab: Well, that might be why it hasn’t come up in your Jewish education beforehand.

Yael: I know, but he’s so interesting. D’Acosta was born in Porto, Portugal, under the name Gabriel D’Acosta Fiuza. I think Fiuza is the appropriate pronunciation. And he was actually born to a converso family. So, his family had been practicing Jews. And in 1497, under governmental edict, they were forcibly converted to Catholicism. He was born in 1585, so his family had been Catholic for a couple of generations by the time he was born. At a certain point in time, having been raised a relatively traditional Catholic, Uriel D’Acosta got interested in reading the Bible.

Schwab: And did he know about his family history? Like that way back when they were Jews and that they had converted to Catholicism?

Yael: So, he only found out that he was a converso when he was an adolescent/young adult. I’m not sure that the year is pinned down, but sometime in his mid-teens to early 20s, was when he found out that he was a Jew. And when his father, who had been a relatively observant Catholic passed away, Uriel and his mother and brothers fled Portugal and they say, ‘converted to Judaism,’ though we would say they never actually left Judaism but started living as Jews.

They left Portugal in 1614, because the Inquisition was really designed to target families like theirs, families that had once been Jewish, then converted to Catholicism, and there were fears that these families might backslide into their Judaism, so this family was actually a perfect object.

Schwab: Apparently, these fears were pretty founded, because that’s exactly what happened here.

Yael: Exactly.

Schwab (03:13): You heard it here first, the Inquisition was right.

Yael: (laughs) Yes. They were perfect objects for the Inquisition. Poster children. So, he and his mother and brothers sort of backslide into their Judaism, and they decide to sneak out of Portugal to the Sephardic diaspora, which was then flourishing in Amsterdam. Two of his brothers went to Amsterdam, he and his mother first go to Hamburg, and then ends up living in Amsterdam later on, and he changes his name from Gabriel to Uriel.

Schwab: Is there a significance?

Yael: I’m not 100% sure, because Gabriel and Uriel are both angels from the Bible.

Schwab: Right, Those are both like Hebrew, Jewish names.

Yael: Yeah, I’m not sure why he made the change. He went by Uriel in the Jewish community, and he went by the name Adam Romez, to outsiders of the Jewish community. And as I mentioned, as a relatively good Catholic as a child and teenager, he had become very, very interested in reading the Bible. And he continued to read the Bible in his life as a Jew. But what he found in the Sephardic diaspora was not what he expected.

Schwab: In what sense?

Yael: He found a community that observed Judaism quite strictly. But the Judaism that they were observing did not, to him, fit with what he read in the Bible.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Because so much of it was based on like the Talmudic tradition. And rabbinic literature, and he was like, “Look at the real text.”

Yael: Exactly. Yes. Exactly.

Schwab: Like he was like a Bible literalist. Somebody poked out someone’s eye and he said, the Bible says an eye for an eye, we got to do what it says.

Yael: I don’t know, you know, how he would interpret …

Schwab: That’s a specific example to come up. (laughs)

Yael: … an eye for an eye, but yes, he was very disappointed that what he saw is this pure Judaism of the Bible was not what was being practiced by these diaspora communities, and so much of it was rabbinic, and very much in the Pharisaic tradition. He did not like rabbis. He thought rabbinic leadership was consumed by ritual and legal technicalities. And he actually used some fairly negative language to refer to rabbis. In his autobiography, he calls them “obstinate and perverse race of men.”

Schwab: Whoa.

Yael: (laughs) Yeah, it’s pretty harsh, I would say.

Schwab: Yeah. (laughs)

Yael: And he felt very fenced in by the restrictions that were placed on the community, so that was hard for him. And I think also, he didn’t necessarily love the character of the community. I don’t know if that was the character of particular people, or just the way they were living their lives, but-

Schwab: Yeah, it sounds like the type of thing that someone could have objections to even in 2023, looking at our community and saying there’s a lot of focus on ritual, and there’s a lot of focus on law. Where’s the respect for the deep principles and values?

Yael: 100%. And, you know, there are often people who become more observant in their Jewish practice today, once they become insiders in an observant community. Sometimes become disillusioned because I think they come to religion thinking that they’re coming to something on a higher plane. And then they get to the nitty gritty reality of day-to-day life and realize that it’s not as sacred as it seems to an outsider.

Schwab: Yeah. So, he’s- he’s not satisfied. He thinks that the rabbis are obstinate and perverse.

Yael: Exactly. (laughs)

Schwab: And it sounds like he’s sort of making his feelings known.

Yael: Exactly. So, he’s not keeping this to himself. I kind of jumped ahead to the point in his life where he was writing and was making things known. Just want to take a step back for a second and talk about him as a person.

And before I do that, I just wanna mention that the remainder of this podcast will deal mental illness and suicide. And if anyone does not feel at the moment like those are topics they’d like to hear about, we’d love for you to revisit us in our next episode, but we wanted to give you that warning.

So, he was a very sensitive child. He refers to himself in his autobiography as a real empath. He felt so much emotion, and he felt the pain of others. And I think when I read that, it makes sense to me that inconsistencies in the world would bother him, because he really feels hypocrisy, and he feels pain that’s emanating from people who maybe don’t 100% fit in the community.

Schwab: And everything you’ve said so far, he’s like a perpetual outsider. First, he is a Catholic converso living in Portugal, and then he is an immigrant to this community in Amsterdam and like, as an outsider, understands and sees all the other people who are outsiders in different ways.

Yael: Exactly. And he takes this emotion during the time he’s living in Hamburg and writes something called the propositions against the traditions, which were 11 theses combating certain elements of Rabbinic Judaism. But not combating Judaism as a whole, just sort of making it known that he sees these inconsistencies in the practice of the observant community versus what he read in the Bible.

Schwab: Were they suggesting different practices? Or it was sort of like just a condemnation of something people were doing?

Yael: I’m not 100% sure. Nothing that I’ve read leads me to believe that he was trying to pull people from the traditionally observant community and, you know, start his own movement or start his own congregation. But he definitely was trying to get these ideas out in the world to the extent that he sends this piece of writing to the Jewish community of Venice, because I think he wants these ideas to start percolating in the community. And the Jewish community of Venice or the beit din or hierarchy of the Jewish community in Venice is horrified by these particular writing.

Schwab: (laughs) Oh, okay. I was pretty sure that’s where you were gonna go, that it wasn’t gonna be like they received this letter and they did some deep introspection and decided to make changes. No, they were not thrilled.

Yael: They were not thrilled at all, and a rabbi, Leon of Modena, wrote a refutation of D’Acosta theses. And he also reached out to the rabbinic establishment in Hamburg to say, “We need to excommunicate this man.”

Schwab: Oh, no.

Yael: So, that was his first encounter with excommunication. And excommunication takes several different forms in different communities, but it really meant that he was no longer welcome within the Jewish institutions of the community. Probably couldn’t live in the same residential areas of the community. And again, an outsider is outsider.

Schwab: That’s the most painful thing that can happen to somebody who’s dealing with the trauma of being an outsider is to be excommunicated. I don’t know if he’s the hero of this story, and I’m supposed to be sympathizing with him, but at the moment, I feel really bad for him. It sounds like he’s trying to make a point and gets pushed out.

Yael: Whether or not you agree with him theologically, you certainly can feel for him as a person, because he had an extremely tumultuous life. We haven’t even scratched the surface. There are terrible things that happened to him in the Jewish community in Amsterdam later on, that we’re gonna get to. So, yes, you can certainly sympathize with him as a person. So, he is excommunicated, 1616. He does some more writing, some more ruminating. 1623, he moves into the Jewish community of Amsterdam, or tries to. The people there are not thrilled about having a known heretic in the midst of their community, and they sort of reaffirm excommunication.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. They’re like, “We got to renew your excommunication.” It’s been seven years, so time to renew it.

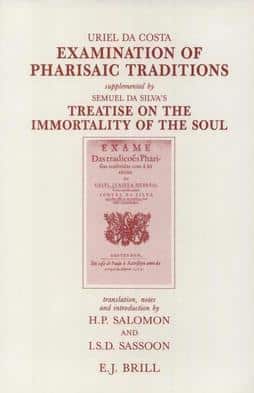

Yael: Exactly. They’re re-upping it. And sometime after 1623, he moves to another Dutch city, Utrecht, and he writes another treatise, even more heretical than the first, at least according to the rabbinic authorities of the day. It’s in this piece of writing that he starts to spread the idea that a close reading of the Torah does not support the concept of immortality of the soul.

Schwab: Right. Now, we’re wading into like pretty controversial stuff that cuts at the base of a lot of beliefs.

Yael: And I think it’s very compatible with his first observation that the observance of Judaism had become too legalistic and ritualistic. Um, because if you don’t believe in the immortality of the soul, if you don’t believe in the world to come, or that one can be rewarded or punished in the world to come, then if a mitzvah, something that a Jew is commanded to do is not utilitarian, does not either help improve your life or someone else’s life, then why are we doing it?

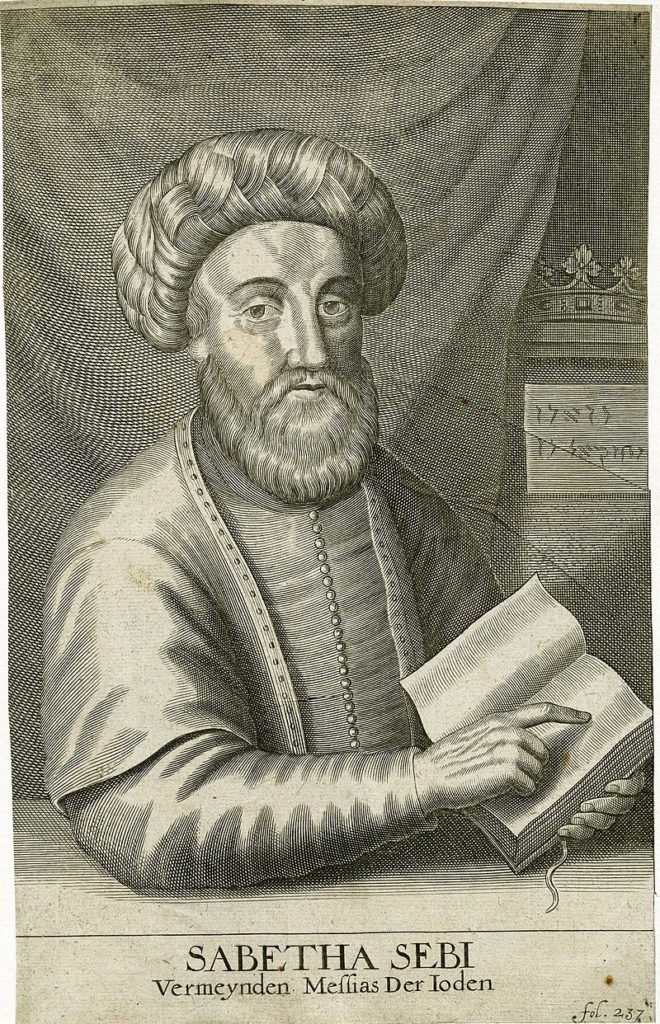

Schwab: Mm-hmm. It’s so interesting. I keep thinking about previous episodes, and it sounds like he’s sort of, in some ways, like the opposite of Shabbetai Tzvi who was talking about, like, everything we’re doing as being, like, sort of good for the world and repairing the world. And he’s saying he’s like dismissing, you know, those notions and saying like, “You should do things that are practically and materially good in the present moment and throw out these like larger questions.”

Yael: You’ve really hit the nail on the head, because …

Schwab: Oh, great. Wow. (laughs)

Yael: … later on, um, skipping a couple of years, he becomes a deist, someone who believes in a deity, but he really becomes someone who rejects the traditional religious law that he had grown up with and believes in the natural law. And I don’t 100% understand natural law, but my sense is very much that it is rooted in doing good for the present. You know, behaving in a way that creates an upstanding and functional society.

So he writes about the Torah not supporting immortality of the soul. And while he’s living in Utrecht, his mother passes away in Amsterdam.

And at this time, he is so well known as a heretic, as someone that Jewish community does not want to associate with, his mother, who to our understanding is someone who preserved a level of Jewishness the entire time she was living as a converso, and was really number one on the bandwagon to go back to Judaism with her son. A question was raised as to whether or not this woman could be buried in the Jewish cemetery in Amsterdam.

Schwab: Just by the association with him?

Yael: Yes. Because she was the mother of Uriel D’Acosta.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Like, it’s a statement, not just that his ideas were so against the rabbinic position, but also that they were dangerous in some way, right? Like the power of excommunication is like we need to clearly set a boundary, like these ideas are not acceptable, and make that very clear to everybody, because otherwise, there’s something attractive about them.

Yael: Yeah. And it goes back to what you were saying about him being like the ultimate outsider. Whether or not you believe in the immortality of the soul, if you refuse to bury someone’s body in the Jewish cemetery, you are rendering them an outsider from the community forever.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: So a couple of years pass and he really is a lonely person. There is a contention that Uriel D’Acosta suffered from some sort of unnamed mental illness. He may have experienced things, saw or heard things, or had thoughts that maybe today we would identify with known mental illnesses. He may have been someone who didn’t behave socially or couldn’t behave socially in a way that other people could. And I don’t think that there was really an awareness of any of that at that time, or whatever awareness there was, was simply, this person is crazy, you know, keep them far away from me.

So, he was very lonely. I don’t think that he had much of a community to speak of religious or secular just because of the type of person that he was. I don’t think he made friends easily or could easily drop right into a community or a workplace.

Schwab: So, he didn’t really have followers or other people listening to the things he was saying. It was just this lonely person writing refutations.

Yael: Right. He was not this charismatic leader like Shabbetai Tzvi was. If his ideas resonated with other people, they may have worked with him, but he was not out there, you know, on the circuit, standing on soap boxes and drawing a crowd.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Yeah.

Yael: And he decides that he’s had enough of loneliness, and he returns to Amsterdam. Even though he really disagrees with the community and how it observes Judaism, he, in his writings, refers to his return to Amsterdam at that time as a choice to live as an ape among apes.

Schwab: Wait, he was in Hamburg, then went to Amsterdam, then …

Yael: Then we went to a place called Utrecht …

Schwab: Utrecht, right, right. Yeah, thank you.

Yael: … which is also in the Netherlands.

Schwab: And then back to Amsterdam. Yeah.

Yael: Back to Amsterdam. So, the community in Amsterdam is willing to take him back in upon certain conditions.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: And I think certain, you know, his assurances that he would live a certain way and not espouse certain ideas.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. And how do we know all of it? Is this … As you mentioned he has an autobiography, and it sounds like there are writings against some of the things he was saying, like we have a lot of contemporary accounts of him?

Yael: He has an autobiography, and I think that within the chronicles of these various Jewish communities, there is a record of him. So we definitely have that contemporaneous evidence, in addition to secondary sources. And I’m assuming, information that was passed down through the years, particularly within the Jewish community in Amsterdam. Apparently, the current day Jewish community in Amsterdam is very sensitive to this story because there is a level of discomfort with the way they treated this young man.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: So, he comes back to Amsterdam.

Schwab: To … you were saying to act as an ape, to be as an ape among apes. What? What does he mean by that?

Yael: That is … I think it- it shows the level of disdain that he has for the way people are living. And, you know, when I think of an ape, and I have absolutely no idea if anyone in the 17th century or Uriel D’Acosta thought this way.

Schwab: (laughs) Did they, right? I haven’t even seen an ape.

Yael: But I think about, I think about mimicry.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: You know, an ape mimics something, not necessarily because they understand it or believe it, but because, what somebody else is doing.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: So, I don’t know if we can attribute that meaning to what he wrote, but that’s at least what I think about when I hear that. Ultimately, he encounters two Christians who are seeking to convert to Judaism, and he dissuades them from doing so. And unlike the traditional dissuasion that the Jewish community usually goes through when a convert approaches them, we often, we wanna make sure that they really know what they’re getting into. There’s a tradition to kind of rebuff them at first and see if they really have the fortitude to come back.

Schwab: Resolve. Yeah.

Yael: The resolve. Yeah, that’s a better word. but what he did was he really tried to dissuade them on the merits of Judaism. Being like, “You guys don’t wanna be Jews.” This is not a thing that you should wanna be, because on its merits …

Schwab: (laughs) Let me prove it to you.

Yael: It’s not worthy.

Schwab: Yeah. (laughs) Right. And it wasn’t like, “Reminder, you’re gonna have to keep all these laws.” It was like, “This system is bad, and you should not want to be part of it,” type of thing.

Yael: So, then he’s excommunicated again, because the Jewish community is not thrilled with what he says to these converts. And there may also have been an incident regarding kashrut that he was involved in that I saw mentioned obliquely in some of the writings, I wasn’t really able to flesh out.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: He’s excommunicated. He lives alone for seven years. (laughs) Then he decides to come back again. And when he comes back, it is only under some very, very, very harsh conditions imposed upon him by the Amsterdam Jewish community. First, he is, um, sentenced to 39 lashes.

Schwab: For coming back.

Yael: Um, yeah. And the number 39 is significant in that under Talmudic law, the punishment of lashes, when it is meted out, the maximum number that can be prescribed is 40. And the reason why we give 39 is because that’s an indication that this person is not the absolute worst person. Like the worst person gets 40 and this person is bad, but he’s not …

Schwab: Really close. He’s really close.

Yael: He’s not at that level. Yes, exactly. So, he gets 39 lashes, and then he has to lay down on the steps of, I believe it’s the synagogue. It may be another, um, large institutional building associated with The Jewish community. And the entire community walks up and down the steps, literally trampling him, stepping on him.

Schwab: And this is his welcome back to the community.

Yael: They didn’t want him back. They were like, “If you want to come back, you are going to have to submit to this level of treatment.” Which is horrifying. It’s very, very sad.

Schwab: I can see why the Amsterdam community doesn’t like talking about this story. Yeah.

Yael: Yeah. Listen, obviously, no one today is responsible for the actions back then. But it is a very tragic and sad story, especially when you think about him as someone who was likely struggling on a biological and psychological level.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. And it sounds like his personality maybe was difficult, and he had trouble getting along with people, and he could be combative, but it sounds like he very much wanted to be included. And that’s the thing that he kept looking for, and yet kept getting pushed away. Or when he was allowed in, it was on terms like what you’re describing.

Yael: This all really is encapsulated in his autobiography, which is written later on. So, he comes back, he gets lashed, he gets trampled. He’s really humiliated.

Schwab: Which shows his resolve for one … Like this is how desperately he wanted to be in this community

Yael: right. The question is did he want to be Jewish, or did he want to be part of something? Because in his autobiography, he expressly states that he wishes he had never come over to the Jews. Which is very sad.

Schwab: Heartbreaking. Yeah.

Yael: Heartbreaking to read. Just quickly gonna wrap up the remainder of his life, and then we can talk about how this resonates today, because I think it is such a compelling story and something that screams out to me in terms of thinking about how we treat outsiders within the community today, and what makes them outsiders.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: Um, he lives in Amsterdam for a few more years, but he really is humiliated. And, you know, his life is not pleasant. And he seeks revenge against either a cousin or a nephew who he thinks maybe was the person who turned him in for one of his excommunications. And in the year 1640, he tries to shoot that person, misfires, misses. I think the pistol he grabs does not work, and he grabs another pistol and shoots himself. So really a tragic life for someone who clearly was a very deep thinker and a sensitive soul. And obviously ruffled the feathers of institutional Judaism, but I have to think that there must have been a better way.

And certainly today, we need to be cognizant of this. And just there has to be a better way to approach, and engage, and welcome people who are on the fringes of our communities.

Schwab: It’s not always easy to understand but some of the things that he was expressing, part of what he was expressing was, I’m in pain, or I’m confused, and some of these things don’t make sense to me. And the reaction was, “You’re totally wrong, and we need to push you farther away.” Rather than, first of all, you’re making good points, maybe, I don’t know, not having read any of his things.

Yael: Mm-hmm.

Schwab: You know, or they’re coming from a place where let’s talk more, let’s have more of a dialogue, let’s get to some sort of understanding, let’s think about some of these things seriously.

Yael: 100%. And I think, you know, we often can justify the treatment of certain outsiders by invoking the rhetoric that they use, like, D’Acosta was certainly someone who was very publicly maligning the rabbis, and the type of observance that the rabbis were supporting. And so, sometimes, even today, we’ll come across people in the Jewish community who say, “I don’t have a problem with that person, or how they live their life, and the choices they make, but they shouldn’t be out there, you know, spreading that gospel.” I think that’s something we hear a lot in a few different areas.

Schwab: Yeah, right, (laughs) in several domains.

Yael: … of modern life.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: Um, and so, how do we approach the people who not only can’t find their place but are critical of the way the community functions? and how do we make sure those people develop healthily, and are safe, and are not likely to succumb to depression or anxiety, or other negative outcomes of not feeling welcome?

Schwab: Right. Like how much does continuing to push people outside worsen some of these things? (laughs) You know, I think people can look at stories like that and say, “Well, like, well, that person was really deeply unhappy or was suffering from a, mental illness, you know.” And like, okay, you can use that to justify being totally dismissive of their points. But the other way of looking at it is, well, how much of that was due to the way that the things he was saying were received and the responses that he got?

Yael: And what did we do to help that person or shape our community to make it a place that can simultaneously make that person feel safe and welcome without compromising what we believe to be, you know, irrefutable religious law? I’m not a rabbi and I’m certainly not someone who makes those kinds of decisions, but those are the concerns I hear from friends of mine who are rabbis or who work in the Jewish community.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: These are really serious issues that needs to be grappled with, because the modern sensibility is to make every space safe and welcoming for every type of person. And I certainly want that to be the case, but I do understand this need to have fidelity to our religion. Because at a certain point, if we make enough changes, it does become watered down. It’s a fine line.

Schwab: And it’s terribly tragic and ironic, but I think about if D’Acosta was focused on the words and the spirit of the Bible. Like the Bible says so many times how sensitive we need to be to outsiders, to widows, to orphans, to people who are, for one reason or another, on the fringe of the community, and how much, you know, maybe part of what he was talking about was himself and this criticism of like we’re so focused on the legalistic and the ritualistic. And we’re forgetting this idea of caring for those in our midst who need the most care.

Yael: That’s a really great point. D’Acosta is someone who even though I had not heard of him prior to preparing for this podcast, he is someone who pops up a lot in the Jewish arts.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: There were several plays in several languages written about him. Um, a very popular Yiddish play. There’s been productions by Habima, which is a very renowned theater group in Israel that have done plays about him. And he is also seen somewhat as an inspiration for Spinoza who is maybe a more well-known heretic, who was seven years old when D’Acosta died.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: And very well may have been inspired by some of his writings and his approach to the Jewish community. But I think it’s so interesting that he is the subject of so many plays and so much art, because I think that artistic and creative people probably identify with his struggle. And that is a huge generalization.

Schwab: Yeah, no. But yeah. (laughs)

Yael: But I think that sensitive souls see a kindred spirit in him. Not everyone in the arts is sensitive, I know. Trust me, I know.

Schwab: (laughs)

Yael: I wish that he was someone who has talked about more in conventional Jewish education just because I think that education resonates more when the students understand that they’re not only being spoon fed the vanilla. And the outwardly attractive stories. Like we can talk about mistakes that have been made. And the treatment of Uriel D’Acosta is, I think, something that there should be some regret about.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: I understand why it happens. And in context, it was certainly to be expected. But I think that if teenagers particularly feel like outsiders, I think to have a story like this presented, but presented as something that we shouldn’t do. We have to be more aware of the outsiders in their community, we have to be more sensitive to them, we have to find their place, even those that are publicly contradicting us. I think it could be helpful to the child who’s feeling on the fringes.

Schwab: Yeah. It’s not a very inspirational story, but it could be, I think, supportive in some of the ways you’re describing. If told in the right way, of like, we acknowledge that there have been characters like this in the past, and we want to do better than that.

Yael: Right. That we are striving to do better, that the insularity of the community doesn’t have to manifest itself negatively as it has in the past. And we are so much more aware now of differences between people.

Schwab: Right. And it sounds like that’s one of the ideas here also of just like, do we draw these strict boundaries of you’re in or you’re out? You can be part of the community or you can be excommunicated. And if you leave and you wanna come back, there’s this very high barrier to entry where we need to literally inflict pain on you to remind you of your place in it. Or do we envision a kinder, more welcoming community.

Yael: Yeah, and it … I mean, we don’t have time to delve into this, but I think to me, it also speaks to, what does it mean to be a Jew and to be a part of the community. Who gets to decide that? And do you have to know that you’re a Jew to be a Jew?

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

Yael: I recently saw Tom Stoppard’s new play, Leopoldstadt, which was excellent and is about a highly assimilated Austrian Jewish family. Uh, the place starts in the 1890s and follows this family through the 1950s. So, you can guess what happens to many of them.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: But the play really emphasizes the extent to which this family felt Austrian. And feeling Jewish was completely secondary. And the reason Stoppard wrote this play is because now, as an adult, he learned that he was a Jew. He was born in Czechoslovakia in 1937. He and his mother left Czechoslovakia as refugees, and his mother married a non-Jewish Brit who ultimately adopted him. That man had the last name of Stoppard.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: And because of his age, Stoppard did not remember that he was a Jew, and no one ever told him that he was a Jew. And when that came out later in life, he had to grapple with that identity, and what it means. And as someone who has never lived a day as a Jew, if at the age of 70 they find out they’re Jewish, is that person a part of our community?

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Yeah. Wow. And that’s such an interesting analog to D’Acosta experience where he grows up not knowing he’s Jewish and then …

Yael: Exactly.

Schwab: Younger than 70, but finds out at some point that he’s Jewish, and starts to think about the question of that identity and ….

Yael: And fights so hard to be a part of any community. because as you mentioned, his identity is intrinsically outsider-ish.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: That’s not a word. Is as an outsider. Because of the fact that he was born to a converso family. And I’m sure that his family was not the only one that dealt with this as there were many, many conversos and crypto-Jews all throughout the Iberian Peninsula, and then in Amsterdam, and in other places. And it seems like something that was, you know, only an issue a long time ago, but, like these are questions of identity that come up all the time.

Schwab: Yeah, definitely. Yeah.

Yael: So, that’s Uriel D’Acosta.

Schwab: Thank you for sharing this story.

Yael: You’re so welcome. I know, I’ll be thinking about him for a long time.

Schwab: Yeah. Yeah. No, I will too. Thank you.

Yael: He’s, um, really a fascinating character, and you know, something to think about in the way that I choose my own community as a person going forward, making sure that the places that I find myself are open, and yet still represent the values that are important to me, and have been important to Jews for thousands of years.