Marilyn Monroe is a legendary icon, with her challenging upbringing, rise to Hollywood fame, beauty, and romantic relationships continuing to draw attention. However, there is one aspect of her life that remains less explored: her Jewish identity and connections.

Monroe was, in fact, Jewish — she converted upon her highly publicized third marriage to the renowned playwright Arthur Miller. Here’s everything we know about her Jewish connections.

The basics

Marilyn Monroe was born as Norma Jeane Mortenson in Los Angeles on June 1, 1926. When she was just a few weeks old, her mother, Gladys Pearl Baker, who suffered from postpartum depression, placed her with a foster family.

It wasn’t until 2022 that DNA testing verified Charles Stanley Gifford — a co-worker with whom Gladys had an affair — as her biological father.

The young Monroe was placed under the care of foster parents Albert and Ida Bolender, evangelical Christians in Hawthorne, California.

At age 7, Monroe returned to live with her mother in Hollywood. However, just over a year later, Baker suffered a severe mental breakdown and was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. Monroe subsequently lived at different family friends’ homes for years.

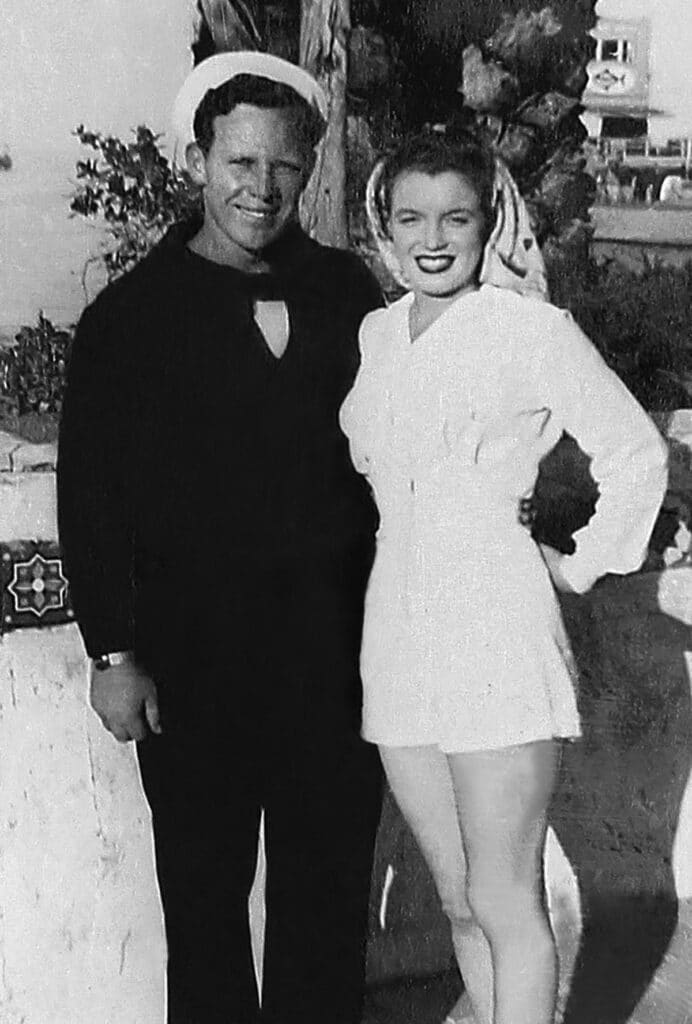

At 16, she married 21-year-old factory worker James Dougherty, but the two divorced four years later.

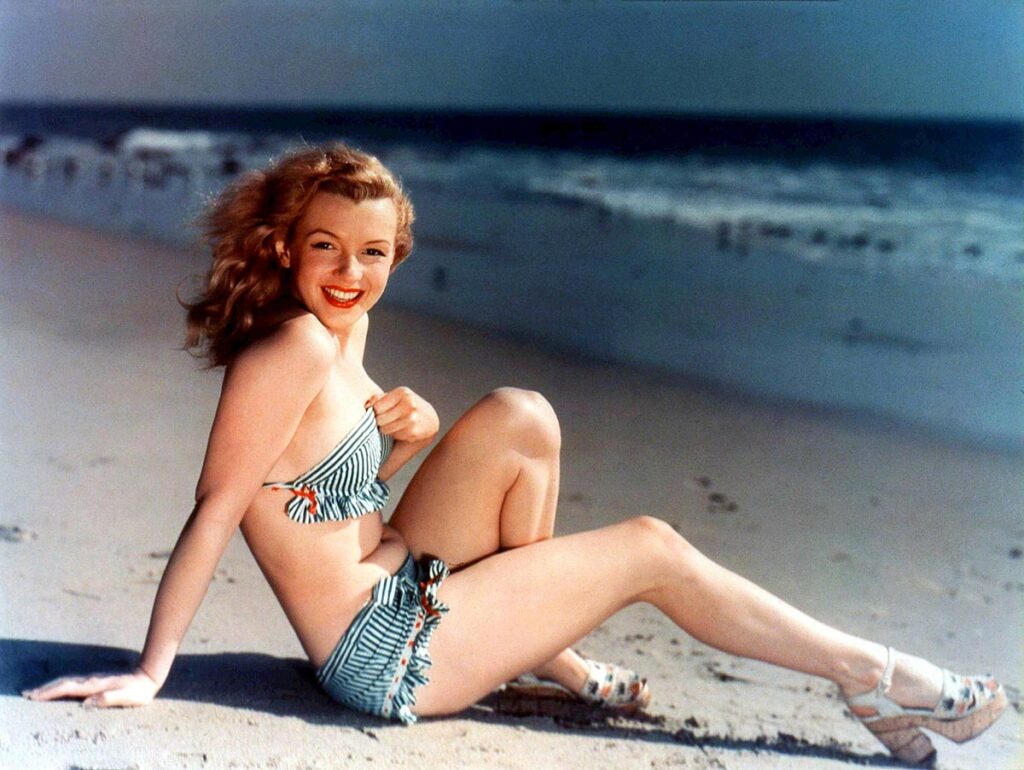

Her modeling career took off in 1944 when she met photographer David Conover while working at a munitions factory. At his urging, she quit her job and started modeling for him, signing a contract with an agency for pin-up modeling a few months later.

Her representative at the agency helped Monroe sign a contract with an acting agency, at which point she started going by her stage name Marilyn Monroe.

As her career progressed, Monroe delivered stellar performances in films like “All About Eve” and “The Asphalt Jungle,” both released in 1950.

The actress renegotiated her contract with 20th Century Fox and began enjoying the love of fans who would send her thousands of letters each week. She gained praise for supporting roles as well, including in the comedies “As Young as You Feel,” “Let’s Make It Legal” and “Love Nest.”

Despite her acting prowess, many continued to view Monroe as solely a sex symbol, a perception she tried to challenge by taking acting classes with famous Russian director and actor Mikhail Chekhov. Her efforts proved successful when she received positive reviews for her roles in “Clash by Night” and “Don’t Bother to Knock.”

In a high-profile turn of events, Monroe and the renowned retired New York Yankees baseball player Joe DiMaggio began dating in 1952, capturing widespread media attention. The two exchanged vows at San Francisco City Hall in January 1954.

Yet, their union was also short-lived, with Monroe filing for divorce nine months later.

Monroe and famous Jewish playwright Arthur Miller were introduced by mutual friend Elia Kazan, a film and theater director, in the early 1950s. At the time, Miller was married to Mary Grace Slattery, a Catholic, and Monroe was in the middle of her divorce proceedings.

In 1956, Miller left Slattery and married Monroe, who converted upon their marriage. Headlines of the time made clear that American Jews felt proud about the match and conversion.

Marilyn Monroe and Arthur Miller had a Jewish wedding

Despite growing up in a religious family and his grandfather serving as the president of his synagogue, Miller never felt connected to Judaism. But the couple did have a Jewish wedding and partook in Jewish cultural traditions.

The couple first wed during a civil ceremony in White Plains, New York, in June 1956. Two days later, they partook in a Jewish ceremony complete with a chuppah and broken glass at Miller’s agent’s house, Kay Brown, in Katonah, New York.

Throughout the years, reports noted how Monroe and Miller’s marriage included Jewish cultural elements that the actress partook in.

Monroe loved the Jewish food that she would eat while visiting her acting coach Lee Strasberg and wife Paula in Fire Island.

“She frequently dug into what Paula Strasberg called her ‘Jewish icebox’ there, with its salamis from Zabar’s on New York’s Upper West Side and the honey cakes and fancy European pastries from some of the bakeries started in New York by refugees from Nazi persecution,” The Atlanta Jewish Times reported.

Monroe also reportedly sprinkled Yiddish expressions into her conversations, like “bubbaleh,” “tuches” and “oy vey.”

Marilyn Monroe converted to Judaism

Reports suggest that, given his own feelings about the religion, Miller never urged Monroe to convert. The star converted on her own accord on July 1, 1956.

“Marilyn Monroe, having sought to join the household of Israel by accepting the religion of Israel and promising to live by its principles and practices, was received into the Jewish faith on July 1, 1956,” her conversion certificate reads.

Reform Rabbi Robert Goldburg, who converted Monroe and officiated her wedding to Miller, said Monroe “was aware of the great character that the Jewish people had produced… She was impressed by the rationalism of Judaism — its ethical and prophetic ideals and its close family life.”

The star once confessed to her friend and fellow Jewish actress, Susan Strasberg, “I can identify with the Jews. Everybody’s always out to get them, no matter what they do — like me.”

However, Monroe gravitated toward Judaism more as a culture than a religion, often describing herself as a “Jewish atheist.”

Joanna Robotham, former curator at the Jewish Museum in New York where she has curated exhibits about Monroe, told The New York Times that the star’s conversation seemed to be “a way for Monroe to gain healthier family relationships.”

Monroe was a Zionist

She also felt a connection with Israel. In 2010, Rabbi Goldburg found a letter that confirmed Monroe was scheduled to deliver a pro-Israel speech at the 1957 United Jewish Appeal conference in Miami.

The star had agreed to speak briefly about “why she became Jewish and why she believed that Jewish institutions and Israel deserved support,” Goldburg said.

The star declined to attend the event on behalf of Miller because of the government’s investigations into her husband’s possible ties to communism.

Marilyn Monroe’s conversion inspired Jewish pride

Monroe’s conversion made Jews feel more secure about their standing in the world, especially after the Holocaust, Robotham said.

“It just showed that Judaism, coming off of the war, wasn’t something people were trying to hide,” she told The New York Times. “They were really celebrating Jewish culture and identity.”

Lila Corwin Berman, author of “Speaking of Jews Rabbis, Intellectuals, and the Creation of an American Public Identity,” agreed, writing, “Marilyn Monroe’s short-lived marriage to Arthur Miller issued a public and celebrated challenge to Jewish sociological distinctiveness.”

“If a person who seemed so clearly not Jewish — from her appearance to her family history to her place in American popular culture — could become a Jew, then the sociological assumptions about Jewishness were in jeopardy of unraveling,” she added (p. 145).

Not everyone celebrated Monroe’s conversion, though. Egypt responded by placing a ban on all of her movies. In 1961, after the couple divorced, the Middle Eastern country lifted the ban and invited Monroe to perform there, but she declined.

Monroe remained connected to Judaism after divorcing Miller

Monroe’s connection with Judaism was deeper than her relationship with Miller. After the couple divorced in January 1961, she continued to engage with Jewish traditions, giving Hanukkah presents to Miller’s children and attending Passover seders conducted by Rabbi Goldburg.

“She never attended synagogue, but Goldburg explained that she avoided most public places for fear of invasive press attention,” author Lila Corwin Berman wrote.

The star famously owned a siddur that is thought to have originated at the Avenue N Jewish Center in Brooklyn, the synagogue that Miller used to frequent. The prayer book went up for auction in November 2018 at an auction house in Cedarhurst, New York, where it sold for over $25,000.

Monroe also owned a kitsch brass-plated menorah that played the Israeli national anthem.

On August 4, 1962, the star was tragically found dead in her Brentwood home. Despite her connections to Judaism, Monroe was not buried in a Jewish cemetery and her funeral was conducted by a Lutheran minister.