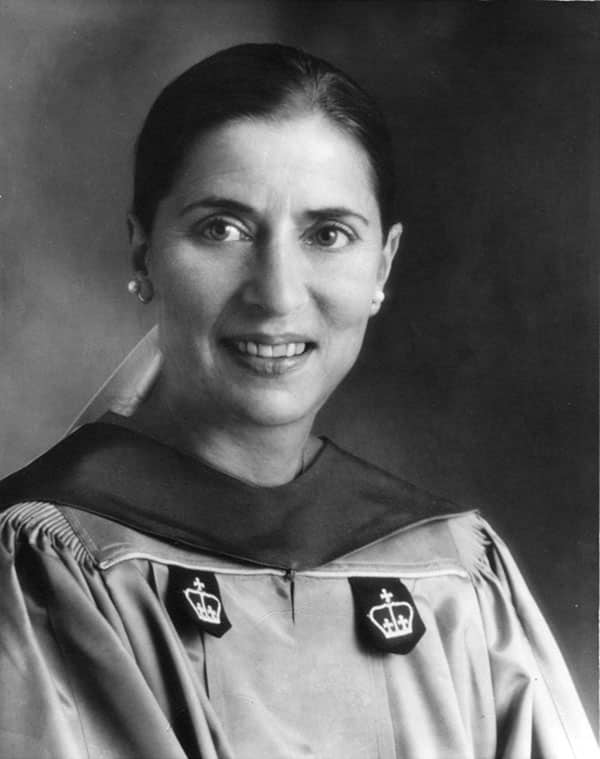

Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the first Jewish woman and the second woman to serve as a U.S. Supreme Court justice, is remembered for championing equal rights for women, Jews, and people of color. She continues to serve as a role model for women and Jews alike due to her inspiring story and character.

Ginsburg famously said, “When I’m sometimes asked, ‘when will there be enough [women on the Supreme Court]?’ and I say ‘when there are nine,’ people are shocked. But there’d been nine men, and nobody’s ever raised a question about that.”

“When I’m sometimes asked, ‘when will there be enough [women on the Supreme Court]?’ and I say ‘when there are nine,’ people are shocked. But there’d been nine men, and nobody’s ever raised a question about that.”

Despite attending Harvard Law School and later graduating as valedictorian from Columbia Law School, she was rejected from over 13 law firms because female candidates weren’t seriously considered. These and other early experiences fueled her pursuit of justice and equality.

Ginsburg often reflected on the influence of her Jewish heritage on her judicial career, emphasizing the Jewish tradition’s demand for justice. Here’s everything we know about her Jewish identity.

The basics

Joan Ruth Bader was born on March 15, 1933, to Celia and Nathan Bader in Brooklyn. Her mother was the daughter of Jewish immigrants from Krakow, Poland, and her father was a Jewish immigrant from Odesa, Ukraine.

She had an older sister, Marilyn, who tragically died of meningitis at age 6, and Ginsburg was raised as an only child. The family endured another tragedy when Ginsburg’s mother died of cancer the day before her high school graduation.

She attended Cornell where she met future husband Marty Ginsburg, and the two married a month after her graduation.

After being rejected from 13 law firms, Ginsburg embarked on a distinguished academic career, teaching at Rutgers and Columbia law schools and co-founding the Women’s Rights Project at the ACLU. This was extremely impressive, as there were only 20 female law professors at the time when Ginsburg entered academia.

Between 1973 and 1976, she successfully argued six landmark gender discrimination cases before the Supreme Court.

In 1980, she was appointed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, and in 1993, President Bill Clinton nominated her as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court. Ginsburg served on the Supreme Court until her passing in September 2020.

Ginsburg struggled with non-egalitarian Jewish prayer

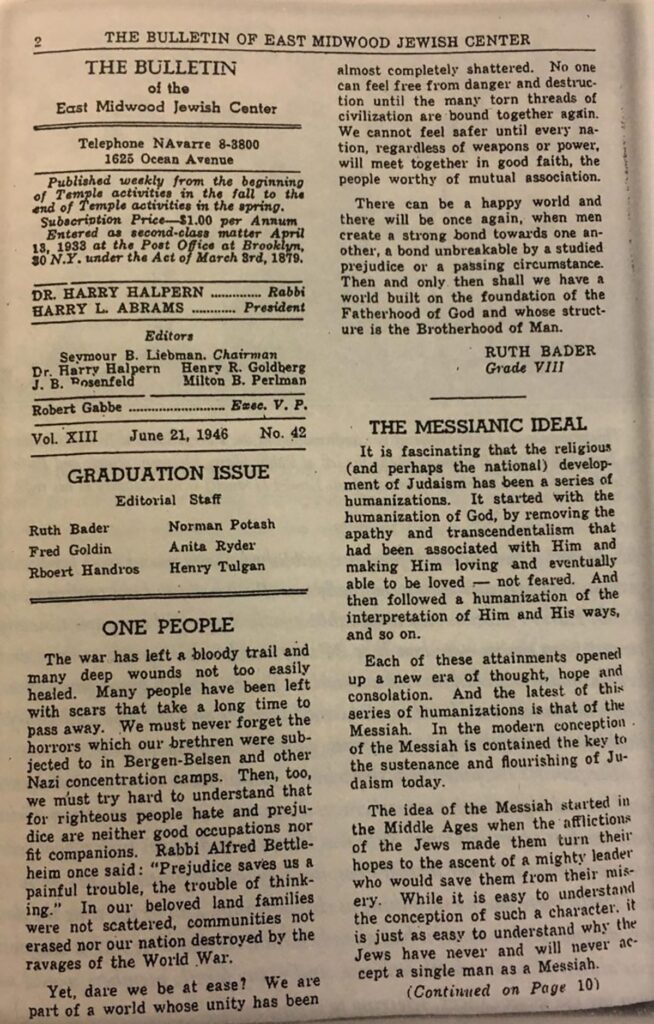

The family belonged to East Midwood Jewish Center, a Conservative synagogue, where Ginsburg attended Sunday school and was confirmed at age 13.

There was no option to have a bat mitzvah (a ceremony that was not yet normalized), and young Ginsburg reportedly felt jealous of her male cousin who had a bar mitzvah.

After her mother passed away, she was excluded from the minyan for mourners, and she felt disconnected from Jewish ritual as a result. This experience conflicted with her feminist views and “made her feel like women really didn’t count,” Julie Cohen, co-director of the 2018 documentary “RBG,” said.

“The idea that…women in your own family didn’t count in a minyan felt supremely unjust and made it hard [for her] to feel deeply part of the religion,” Cohen added.

Despite her challenges with traditional Jewish observance, Ginsburg maintained a strong connection with Jewish values. In an essay for her synagogue bulletin dated June 2, 1946, a 13-year-old Ginsburg addressed the deep scars within the Jewish community:

“We must never forget the horrors which our brethren were subjected to in Bergen-Belsen and other Nazi concentration camps…There can be a happy world and there will be once again, when men create a strong bond towards one another, a bond unbreakable by a studied prejudice or a passing circumstance.”

She served as a junior rabbi at a Jewish summer camp

Ginsburg attended Camp Che-Na-Wah, a Jewish summer camp for girls located in the Adirondacks, New York, each summer starting at age 4. She was later a camp counselor there until age 18.

At age 15, she informally assumed the role of the camp’s “junior rabbi.” In this capacity, Ginsburg delivered the Saturday morning sermon and led Shabbat prayers, showcasing her early leadership skills and engagement with Jewish traditions.

She experienced antisemitism growing up

Ginsburg openly discussed the antisemitism she faced growing up, saying this made her “alert to discrimination.” During her Senate confirmation hearing in 1993, she shared:

“I grew up during World War II in a Jewish family. I have memories as a child, even before the war, of being in a car with my parents and passing a place in [Pennsylvania], a resort with a sign out in front that read: ‘No dogs or Jews allowed.’ … One couldn’t help but be sensitive to discrimination living as a Jew in America at the time of World War II.”

She also spoke about how Jewish children of her generation had to work extra hard “because the best schools had quotas” for the number of Jews they would admit.

At Cornell, Ginsburg was placed in a dormitory of only Jewish women, stating she felt they were placed together so they “wouldn’t contaminate” other students.

Ginsburg connected with the Jewish value of justice

Ginsburg’s husband Marty described the family as “not wildly observant,” but they did celebrate holidays like Passover and the High Holy Days. Ginsburg’s children, Jane and James, attended a Hebrew school in the New York area.

Throughout her life, Ginsburg maintained a proud connection to her Jewish heritage. This connection influenced both her personal life and professional ethos, reflecting her commitment to justice and equality.

“I am a judge born, raised and proud of being a Jew,” she wrote in an essay for the American Jewish Committee in 1996.

“The demand for justice runs through the entirety of the Jewish tradition. I hope, in my years on the bench of the Supreme Court of the United States, I will have the strength and courage to remain constant in the service of that demand,” she added.

She adorned her office with Judaica

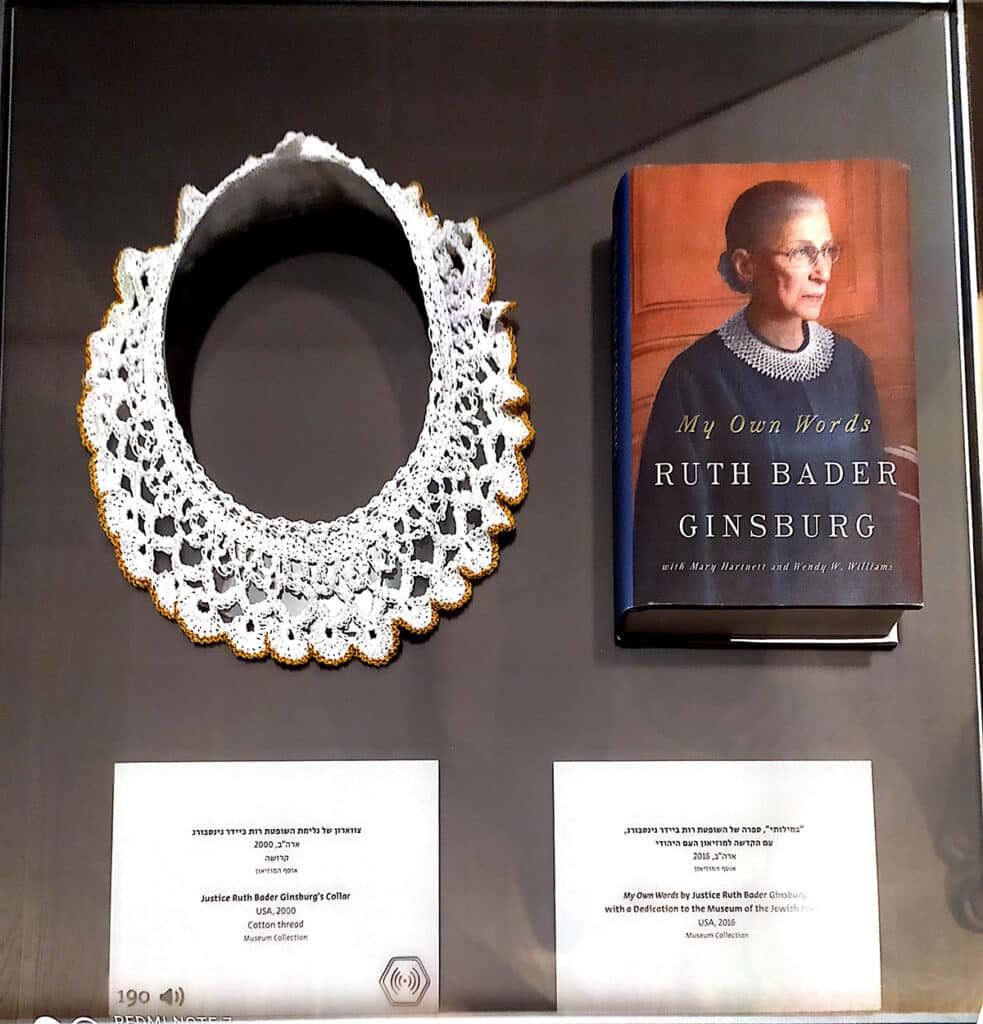

Ginsburg prominently displayed symbols of her Jewish faith in her office, reflecting the deep connection she felt between her heritage and her role as a judge.

She famously put a large silver mezuzah on the door and hung a Hebrew poster bearing the phrase “Tzedek, tzedek tirdof” (“Justice, justice shall you pursue”) from the Torah (Devarim/Deuteronomy 16:20).

In 2019, she incorporated this verse into the collar of her Supreme Court robe. For Ginsburg, these symbols served as constant reminders of the judicial pursuit of justice and the Jewish values that inspired her career.

“I take pride in and draw strength from my heritage, as signs in my chambers attest: a large silver mezuzah on my door post, gift from the Shulamith School for Girls in Brooklyn; on three walls, in artists’ renditions of Hebrew letters, the command from Deuteronomy: Tzedek, tzedek, tirdof’ — Justice, justice shall you pursue,” Ginsburg explained in a 2004 speech.

She embodied the value of civil disagreement through her friendship with Antonin Scalia

Jewish tradition celebrates diversity of opinion and a healthy spirit of disagreement, values that Ginsburg embodied through her unlikely friendship with fellow U.S. Supreme Court justice Antonin Scalia.

The two justices, who sat on the Supreme Court together for nearly 23 terms, had vast ideological differences, often finding themselves on opposing ends of major decisions.

Yet, despite their contrasting views, they managed to be good friends, sharing their love of opera and holding a tradition of celebrating New Year’s Eve together.

Scalia’s sons — Eugene Scalia, the former U.S. Secretary of Labor, and Christopher Scalia — commented on their unlikely friendship and the invaluable lessons it offers to all.

“What we can learn from the justices — beyond how to be a friend — is how to welcome debate and differences,” Eugene wrote. Christopher agreed, writing, “Political disagreement need not turn friends into enemies. My father and Justice Ginsburg mastered this balance.”

In a world often marked by divisiveness, Ginsburg and Scalia’s extraordinary bond reminds us of the importance of respectful discourse, showing that friendships can flourish even amid profound disagreements.

Ginsburg was actively involved in Holocaust remembrance

In 1993, she had the honor of presenting the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Medal of Remembrance to Emilie Schindler, widow of Oskar Schindler.

In 2004, she delivered a poignant speech at the museum on Holocaust Remembrance Day, emphasizing the crucial role of law in preventing atrocities.

“In striving to drain dry the waters of prejudice and oppression, we must rely on measures of our own creation — upon the wisdom of our laws and the decency of our institutions, upon our reasoning minds and our feeling hearts… In our long struggle for a more just world, our memories are among our most powerful resources,” she said in her speech.

She visited Israel five times

Ginsburg’s trips to Israel often centered around issues of gender equality, human rights, and the pursuit of justice, which were central to her life’s work and beliefs.

She first visited Israel in 1977 as part of her studies at Columbia Law School. During her time in Israel, she studied the Israeli legal system and even co-authored a book titled, “The Israeli Legal System: Case Studies in American and Soviet Law.”

During her highly publicized last visit in 2018, Ginsburg received a lifetime achievement award from the Genesis Prize Foundation for her “groundbreaking legal work in the field of civil liberties and women’s rights.” She toured the Old City and asked about the separation of women and men at the Western Wall.

She refused to work on Yom Kippur

The U.S. Supreme Court term commences on the first Monday of October each year, and in 2003, that coincided with Yom Kippur.

Although Ginsburg was not religiously observant, she did not work on the High Holidays. Ginsburg was able to delay the commencement to Oct. 7, even though the commencement date is a federal law.

She shared how she convinced Chief Justice William Rehnquist to do this in an interview with The Forward:

“I explained to him that lawyers wait their entire career to appear before the Supreme Court. For many of them, it is a once-in-a-lifetime chance to argue in the Supreme Court. What if a Jewish lawyer wanted to appear in court? We should not make that lawyer choose between observing his or her faith and appearing before the Court. That persuaded him and we changed the calendar.”

“The Notorious RBG”

Ginsburg became a pop culture icon known as the “Notorious RBG,” a term that was popularized in 2013 by Shana Knizhnik, a law student at the time, who had a Tumblr account by the same name.

The moniker, which plays on the nickname of rapper The Notorious B.I.G., quickly evolved into a cultural phenomenon, symbolizing Ginsburg’s unique and trailblazing status as a U.S. Supreme Court justice focused on women’s and minority rights.

The associated memes, quotes, and artwork celebrated Ginsburg’s contributions to gender equality, women’s rights, and social justice. It highlighted her powerful dissents and unwavering commitment to justice, resonating with a wide audience, particularly millennials and Gen Z.

The “Notorious RBG” movement expanded beyond the internet, with books, documentaries, and even merchandise featuring the iconic moniker.

Her legacy transcended the courtroom, making a mark on the collective consciousness of a generation who saw her as a beacon of justice and a leader in the ongoing struggle for equality.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s legacy of justice

Throughout her illustrious career, Ruth Bader Ginsburg achieved remarkable milestones in the pursuit of justice, leaving an enduring legacy. Here are some of her notable accomplishments:

- In 1996, she authored the majority opinion in a case concerning the Virginia Military Institute, striking down the institution’s male-only admission policy, a pivotal moment for gender equality.

- Her passionate dissent in the Lilly Ledbetter case surrounding gender-based pay inequities sparked crucial legislative change. It led to the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act, a landmark achievement in the fight against gender pay discrimination, signed by President Barack Obama in January 2009.

- In 2013, her powerful dissent in the Shelby County case underscored her commitment to protecting minority voting rights.

These accomplishments, among others, highlight Ginsburg’s profound impact on women’s rights, minority rights, and the ongoing quest for equality in America.

Originally Published Jan 31, 2024 02:31PM EST