Yael: I did take philosophy my freshman year of college. The only thing I remember about it was that we understand a concept of green and we understand a concept of blue. And together, they are “grue.” And do we understand the concept of “grue”? And no, I don’t understand.

Schwab: My roommate and very good friend majored in philosophy and he would tell me about various things that he was studying. And none of them made any sense to me at all until I watched the show, The Good Place. And all of a sudden I was like, why didn’t you explain it like a sitcom the whole time?

Schwab: Welcome to Jewish History Nerds, where we do exactly what it sounds like, nerd out on awesome stories in Jewish history.

Yael: I’m Yael Steiner and my childhood dream was to stay in school forever.

Schwab: I’m Jonathan Schwab and I am in school forever. Yael, this week you’re gonna be teaching me something. So what do we have?

Yael: So I personally think we have a fascinating topic. Our topic is Moses Mendelssohn. Are you familiar?

Schwab: I signed up for a course on Moses Mendelssohn that I so disliked that I’m pretty sure I just totally stopped going to the class. I may have forgotten to drop the course.

Yael: I have dreams that I forget to drop a course all the time.

Schwab: Oh, I absolutely have that. Yeah, that recurring nightmare that I wake up and I have a final that I have to take for a course that I haven’t gone to in all semester. Yeah.

Yael: Yes, yes! And I have to convince the registrar that I actually did mean to drop it.

Schwab: Oh my God, it’s the exact same nightmare. So that kind of did happen actually with this Moses Mendelssohn courses. I just totally stopped going and then just never handed in a final paper. And I think, to this day, I have no grade in this course. But it’s because I so disliked the course. So I don’t know, I guess you have 30 to 40 minutes to correct this traumatic experience in my past?

Yael: I’m hoping that your extremely negative review of the content of the class has not turned off some of our listeners because I actually think he is fascinating, and hopefully I can win you over.

So Moses Mendelssohn is a really multifaceted individual. He is known, particularly in the Jewish world, as the grandfather of the Haskalah. Haskalah is the Jewish enlightenment. It translates to something more like wisdom, but it was meant to be a corollary to the enlightenment that was happening all over the world in the 18th century. But I don’t think that Mendelssohn himself would necessarily have agreed with that title.

He also is claimed by many different denominations of Jews as an inspiration, particularly now we hear about Mendelssohn as the inspiration for Reform Judaism, which developed in Germany in the 19th century after Mendelssohn died. He was what we would call today an Orthodox Jew in terms of his observance. He heeded halacha, Jewish law, but he revolutionized the way Jews talk about the modern world and can synthesize Judaism and lived religion into the modern world. And the reason why he was able to do that was that the Enlightenment was flourishing everywhere else in the world.

Schwab: Okay, cool. I’m a little hooked so far. You’re doing a better job explaining it than it was done in this course.

Yael: Okay, good. I’m trying. I’m gonna talk a little bit about him biographically, but before I even start with the biography, I wanna just throw the notion of legacy out there. We actually know that none of Mendelssohn’s descendants stayed Jewish.

Within two generations, his children were not Jewish. And just as a side note, he is the grandfather of the composer Felix Mendelssohn, who was not Jewish and wrote the wedding march that they play at the end of weddings. Not Jewish weddings generally, but, you know, movie weddings and real weddings probably.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Real weddings. Not Jewish weddings, but real weddings.

Yael: So there is something that is often not attributed to Mendelssohn as having been said by him, but is usually tied to his legacy. It’s a statement, m’Moshe ad Moshe lo kam ke’Moshe, which translates as, from Moses to Moses, there did not arise another Moses. So it’s originally meant to describe Maimonides as being a great Jew on the level of the original Moses, Moses of the desert, but his students ultimately see him as a great leader of Judaism, just as Moses was and Maimonides was.

Schwab: Wow. That’s pretty esteemed company.

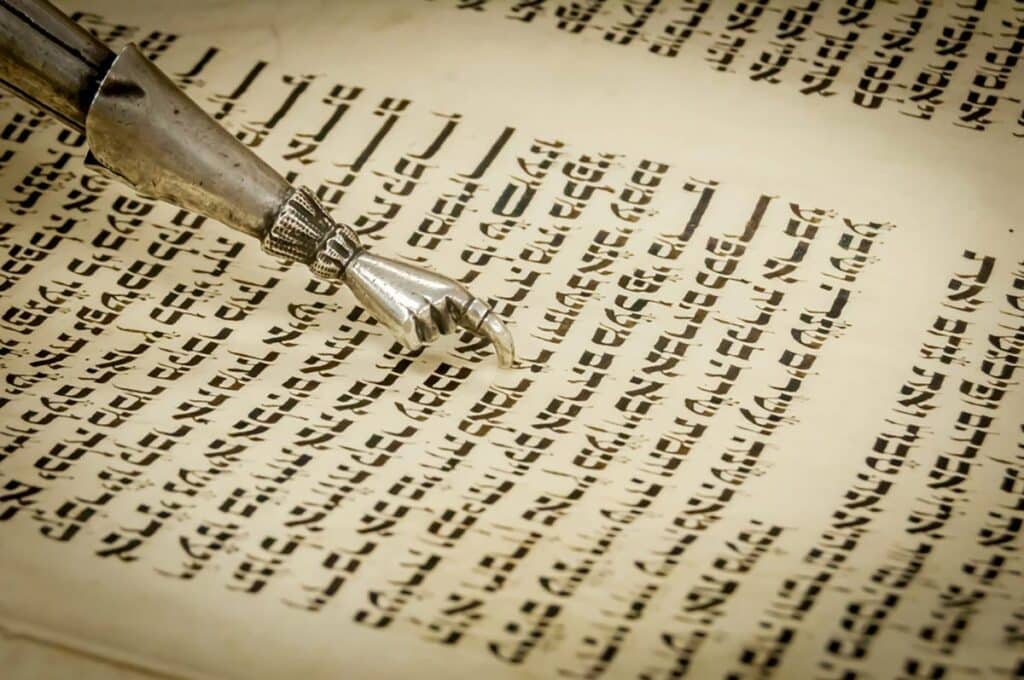

Yael: So they really do, yes, adulate him. So Moses Mendelssohn was born in Dessau in 1729. That was part of Prussia at the time. And he was born into an observant family. His father was a scribe and he was also something known as a klopper. A klopper was someone who would walk around the town and bang on the wooden shutters of the buildings to wake the men up to attend services in the morning.

What I find really interesting about this is that his father worked in a profession where he literally transmitted Jewish tradition by being a scribe, writing tefillin, Torah scrolls, mezuzahs, and he also worked as someone who awakened the community.

So I know it’s a little cheesy, but I do think we see the generational tie between him and his father. Not only that and what’s interesting is that you go in the other direction and his descendants are no longer Jewish. So he has a very interesting relationship with both sides of his family tree.

Schwab: Wow, yeah.

Yael: So he’s a very successful student. He’s a student of the rabbi in Dessau named Rabbi David Frankel. Rabbi Frankel moves on to Berlin and Mendelssohn follows him because to continue his studies, he masters Talmud, he masters the Bible, he masters a lot of more esoteric texts. And in Berlin, Mendelssohn, as a Jew, and not a particularly rich Jew or a Jew of a particular profession, is not really allowed to live legally and-

Schwab: Like he’s not allowed to live in the city?

Yael: Correct, correct. Jews were not permitted to live there. Certain Jews were protected. They were granted the right of residency that usually came with some sort of fortune or some sort of relationship to a high-ranking official. Mendelssohn ultimately gains this.

Schwab: If your father banged on wooden shutters, you weren’t at that high level.

Yael: Yeah, it’s not the right yichus, as they say. He does ultimately gain residency status in 1763. That’s after he completes a major accomplishment that we’ll get to in a few minutes.

Schwab: Hmm. Ooh. I’m so curious.

Yael: But up until that point, he’s living illegally. He lives with a few different families where he tutors. He’s really an autodidact and clearly had an ear for languages because he’s able to learn several of them. And he ultimately ends up living with the family of a silk merchant as a teacher to that family. And then he starts working in that silk factory, and he works his way up, ultimately, many years later, becoming a partner in that silk factory.

So to me, he’s sort of a combination of Good Will Hunting, Andy Dufresne, Perchik from Fiddler on the Roof, where he’s self-taught. He ingratiates himself to his employers and makes himself irreplaceable. He works his way up, and he’s also someone who’s spreading newfangled ideas to the families that he’s working with.

Schwab: Which is very cool. It’s not just a rags to riches, pull yourself up by your bootstraps type story, but it’s like pull yourself up by your bootstraps and also instead of going to sleep at night, read through lots of books and teach yourself multiple languages.

Yael: Right, he was able to sustain himself economically, and he also undertook a secular education at that time. So he was not only well-esteemed in the yeshiva, the yeshiva in Berlin that he attended was called the yeshiva of 40 students, because apparently it was there was an endowment for 40 students to learn, and they would get a small stipend, but that stipend was really, really small. Mendelssohn says that at a certain time, he was only getting a loaf of bread a week, and he would score it into seven pieces so he would know how much he could eat on any particular day. But he does, as you say, bring himself up by his silk bootstraps and ultimately becomes a partner in this factory.

Schwab: Wow. And he’s also getting a secular education at the same time.

Yael: Yes, the enlightenment is happening around him. There are a lot of really interesting public intellectuals in Berlin, and he undertakes the study of philosophy. And the philosophy that he writes is incredibly well received and still stands today as a real example of academic philosophy that is esteemed, but it is so far over my head.

Schwab: I was gonna ask, what are some of his ideas?

Yael: So he talks a lot about ontology and metaphysics.

Schwab: Now I’m remembering, yeah, things that I didn’t like about this course.

Yael: I was going to say, those are words that when they’re dropped into conversation, I sort of nod my head and pretend that I know what’s going on, but not so much. However, Mendelssohn truly understood metaphysics to the extent that in 1762, he comes in first in this essay contest where he writes about the metaphysics of theology and argues that theological notions can be proven to the same level of certainty as mathematics.

Schwab: Hmm, interesting. Did they know he was Jewish when he won first place?

Yael: They did, and several years later when they tried to admit him to the academy and they did vote to admit him, his admittance was eventually thrown out by the king who refused to admit a Jew.

Schwab: This came up in a previous episode of someone was supposed to win an essay contest and then they couldn’t because they were Jewish.

Yael: Hannah Senesh, she was supposed to be the editor of her literary magazine. It’s so weird that you said that because the whole day I was thinking about Mendelssohn as a Renaissance man, which is totally not the right descriptor for him because he’s specifically an Enlightenment man, but he’s good at so many things. And that’s how I felt about Hannah Senesh and that’s how I described her. The reason I didn’t bring it up myself was that I have no indication that Mendelssohn was athletic and would have been able to jump out of a plane.

Schwab: Right. Did not undergo parachute training.

Yael: Correct. So it’s not to say that he couldn’t have if such things had existed in the 1700s.

Schwab: Right, if airplanes had existed at Mendelssohn’s time.

Yael: Right, but I didn’t wanna put him out there as something that he might not have been because he’s enough things. The person he beat in that essay contest was Emmanuel Kant.

Schwab: Hmm, I have heard of him.

Yael: I was going to say, even I know enough about philosophy to know that that’s a very big deal.

Schwab: Yeah, wow. Did they know each other? Like they’re not just contemporaries, but did they ever meet or interact or?

Yael: I don’t want to say with certainty, but they certainly moved in the same philosophical circles. Mendelssohn considered himself much more a student of Leibniz, who, to my understanding, presented counterarguments to Kant. So I think they were of two different schools. But again, when it comes to philosophy, I see the word metaphysics and everything is just garbled.

Schwab: If anyone out there is listening and wants to start a podcast called Jewish Philosophy Nerds, this would be a great topic for an episode, sounds like.

Yael: I did take philosophy my freshman year of college. The only thing I remember about it was that we understand a concept of green and we understand a concept of blue and together they are grew. And do we understand the concept of grew? And yeah, no, I don’t understand.

Schwab: My roommate and very good friend majored in philosophy and he would tell me about various things that he was studying. And none of them made any sense to me at all until I watched the show, The Good Place. And all of a sudden I was like, oh, now this is what you were saying? Why didn’t you explain it like a sitcom the whole time?

Yael: It’s amazing what Ted Danson can do.

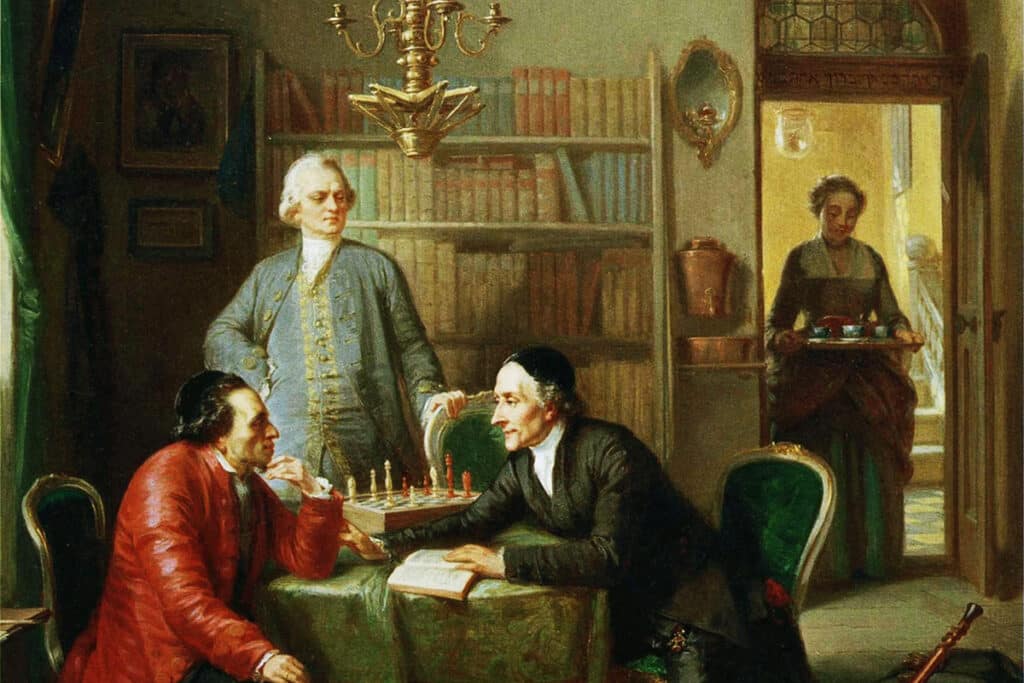

Another area where Mendelssohn really made a name for himself was in the world of literary criticism. And I think that was something that brought him to more people than philosophy did. I think more people read book reviews than read epistles on metaphysics. So, He befriends someone named, Something Gotwald or Gottheim Lessing. Something with a G, Ephraim Lessing, who was a big deal in the drama world and in the world of literature. He teams up with Lessing and with Nikolai, who is another public intellectual of the time. And together they publish a pamphlet, which somebody I heard talk about this likened to Reader’s Digest, where it was something with small easily digestible essays that appealed to a much more mass audience than what he had been writing beforehand. And these were not on Jewish topics.

Schwab: Like philosophical ideas or ideas about art or literary criticism.

Yael: I think they’re ideas about literature and only two editions of this newsletter pamphlet thing were ever published, which is very sad, but it was enough to make it something that we do remember him for now. More interestingly, he is still living his life as an observant Jew, which is not what you would expect. Because up until this point in history, there is no template for living as a Halakhic Jew in the modern world. And also it’s the first time in history where Jews might even have a chance to be admitted to these circles. So Jews had not yet been emancipated, which meant that they could not live in the center of most cities. They had to live on the outskirts. In Berlin in particular, Jews were only allowed to enter and exit the city through a gate that was used for cattle. So still very much not full citizens. And Mendelssohn, aside from his academic pursuits, really makes it a mission to advocate for the emancipation of Jews in Germany, which is not something that happens unfortunately until after his death.

The only place in the world where it actually does happen before he dies is the United States, where Jews aren’t really “emancipated,” they are just free and equal citizens from the beginning. But the Declaration of the Rights of Man, which is part of France’s adoption of emancipation and the rights of regular citizens, only comes into being three or four years after Mendelssohn dies.

So he’s making a tremendous name for himself in the academic world. And he is presented with a challenge by a Swiss theologian named Lavater. Lavater had heard about Mendelssohn, as many, many people had, not that many people defeat Kant in an essay contest.

Schwab: Was that essay contest that was like when they were young? Or this is like, as adults, like Kant is already, it’s not like, oh, he beat him in high school and then Kant went on to become Kant, but like people already knew who Kant was.

Yael: Mendelssohn was in his 30s. And because Mendelssohn was on this level, Levater, this theology student in Switzerland, heard of him and came to admire him. And, as a very good Christian, thought, this is a good guy, this is a good, smart guy. He should be Christian.

Schwab: Oh no.

Yael: We’re also talking about, we’re now after the Protestant Reformation, most of the people that we’re talking about here are Lutherans. But you also have Calvinism, where if you’re somebody who does good deeds and takes good actions, that indicates to the rest of society that you’re saved. And Lavater says, this is a good person, shouldn’t he be Christian? And writes to Mendelssohn about this. Mendelssohn writes back in a letter that is both politically astute and religiously astute, I think. He doesn’t react forcefully or angrily, he basically says, I’m a minority and it’s not politically expedient for me to put Christianity down, but my conception of Judaism does not put Christianity down. My conception of Judaism is that Judaism is for Jews and Jews are halachically bound, and everyone else is only bound by the seven Noahide commandments, which are basically, you know, be a good person.

Schwab: What an interesting response also to religious argumentation. That Lavater, I assume, is coming from the angle, basically, of, Christianity is right. You clearly are an intelligent man of reason. You should be able to see the logic here. And Mendelssohn isn’t like, let me prove to you that Judaism is right. He’s like, you do you, I don’t have to reject your perspective to feel like mine is true for me.

Yael: And that is representative of who Mendelssohn is writ large because he is a person who says, I can be a Jew. I can believe what I believe and I can live among you and you don’t have to change me and I don’t have to change you. And now today, some people say that was the beginning of the end for observant Judaism because that’s the beginning of assimilation.

And other people say that is the only way that Judaism can exist in the modern world. And without that, we would have lost many more people.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Like that’s the model. Right, I see, now I see what you’re saying. Right, oh, just like that. I can see how Mendelssohn is the model for lots of different options.

Yael: Yes, exactly. But Mendelssohn is the person who to me most exemplifies the tension that occurs in Judaism at the dawn of modernity. What does it mean to be a Jew as soon as you no longer “have” to be a Jew? As soon as you’re allowed in the public square. As soon as you’re allowed to undertake higher education. So what is Judaism when you no longer live only among Jews? And at this point in time, when he responds to Lavater, Mendelssohn redirects a lot of his resources toward Judaism. Before that he was really doing more of the secular philosophy though, can’t even call it secular because all it is dealing with the existence of God or the non-existence of God. He also has a big thing about the immortality of the soul which is something we talked about last season also.

Schwab: Yeah, Sarra Coppia Sullam had a lot to say about the immortality of the soul. This is around the same time, right? That was…

Yael: I think that was the 1600s, not so much earlier.

Schwab: Still stuck on this immortality of the soul question. 250 years later, I don’t know that we’re like still there yet, but yeah.

Yael: Yeah, I mean, AI raises a whole bunch of questions about the soul and the immortality of the soul. But yes, so Mendelssohn now starts writing more about Judaism. And one of the things that he does that is controversial to this day, though maybe wouldn’t seem to be controversial if you’re taking it out of context, is he translates the five books of Moses, the Torah portion of the Tanakh, the Pentateuch, into German. And he does this in a transliteration written in Hebrew letters. So he uses Hebrew letters to write out the German words that have the meaning of the Torah text.

Schwab: So it’s for Jews who can read Hebrew letters but speak German.

Yael: Well, what the impetus for it is to get more people to understand German.

Schwab: Oh, interesting. I thought it was like, Jews who have a better understanding of German language than biblical Hebrew but can’t read in German. They know the Hebrew sounds, but they really, you know, speak German and, this is a good way to understand because biblical Hebrew is not the easiest language, especially because it’s not a spoken one anymore.

Yael: So it’s actually the opposite.

Schwab: Okay, he’s trying to teach them German.

Yael: He’s trying to teach them German. And he in fact calls it the first step toward culture.

Schwab: I see how that would be controversial.

Yael: Yes, and it becomes a huge bestseller. It becomes the number one study Bible at the time.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. Right. It’s not about making the Torah text more accessible to Jews. It’s about using this text that they’re familiar with to get them to learn a different language and step outside of that.

Yael: Correct. And all of a sudden they’re exposed to an entirely new world. If they don’t speak German then they can’t assimilate. But once you open up German to them an entire world becomes accessible and that’s where particularly the more observant and the Eastern European rabbis are turned off. But Mendelssohn is praised for this in Germany and now he’s known for more than just his philosophy.

Schwab: Yeah, right, that’s a totally different thing to do than publish monographs on metaphysics.

Yael: Here we have someone who’s known as the Socrates of Berlin merging his identity as the Socrates of Berlin into his identity as Moses of Dessau, who he was before he was exposed to the outside world.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. And his father who painstakingly rewrote the words of the Torah as they’ve always been written.

Yael: Right. Yeah, that’s really interesting. I didn’t think about that, but it’s very fascinating that you say that about his father being a scribe and him translating the Bible into writing those same Hebrew letters to make it more accessible to Jews, but writing German words so that they learn something.

Schwab: Yeah, because the whole job of a scribe is to write it exactly the same, right? Like not to change the text in any way, you know? And Mendelssohn is changing the text. Right?

Yael: Yeah, you know, when you publish a translation of the Torah, you don’t need a scribe, because that at least under our current understanding is not on the level of holiness that it would be written on parchment as a scribe would write it. It can be used for study and it has utility, but it’s not holy in the way a Torah that’s written by a scribe on parchment is holy. So it’s actually inherently not holy if you look at it that way, which is interesting.

Schwab: Yeah. Did he have to defend himself from this criticism? Did he explain what it was that he was trying to do?

Yael: After Lavater, he started writing more about Judaism and he started writing more about Jewish philosophy, in addition to translating a bunch of texts, he translated some of Maimonides’ texts to go back to the, you know, m’Moshe l’Moshe, lo kam ki’Moshe. And he starts writing more about, I don’t know if it’s necessarily to defend himself, but more about his thoughts on theology. And he has his seminal work known to us as Jerusalem. It has a really long German name that clearly does not translate to the word Jerusalem. And in it, he makes the argument that religion cannot be coerced, which is a new idea and very much forces aside the Jewish authorities of the day, the Jewish courts, the beit din, who were coercing people to do certain things.

Schwab: Like religious practice for individuals can’t be coerced, beliefs can’t be… What does he mean by that?

Yael: Correct. He basically means that religious action is religious only to the degree to which it is performed voluntarily and with proper intent. That’s a translation of Jerusalem. So he’s saying that if you’re coercing someone to do something, it’s not religious. It’s inherently not religious. And there’s no point.

Schwab: Hmm, interesting.

Yael: Like, someone has to make the decision themselves to undertake Jewish practice. And he’s not advocating for doing away with Jewish practice. He’s advocating for people to want it themselves.

Schwab: Have more agency and authority in deciding that for themselves.

Yael: So the subtitle of Jerusalem is, or on religious power and Judaism. So he even puts it upfront that this is really, this is about coercion and this is about choice within Judaism. And one of the things that he talks about is that because there’s choice and because every person, believes in divine goodness. And every person is destined ultimately to enjoy the degree of happiness appropriate for him. We need to be civically engaged and politically expedient, as he’s noted before, and that certain things about Judaism maybe can be tweaked for civic duty, which is also obviously very controversial and also could be seen as a forebear of some of the denominations of Judaism today. One example of this has to do with Jewish burial. As you probably know, Jewish burial is supposed to take place as soon as possible after a person passes away. That is considered the most respectful way to treat the body of the dead and that is something that we often try to move mountains for, even today.

There was some kind of issue in the 1700s, I got it right this time, the 1700s, where people were being prematurely buried such that they were buried alive.

Schwab: Oh god. Okay. I feel like I’ve heard something of, they had to appoint people in the graveyards to listen in case people were rising out of their graves to make sure. But I always thought that was made up.

Yael: So I didn’t hear about that, but it makes sense because science had advanced enough that we understood the heart and breathing to a certain extent and that if your heart was no longer beating, you ultimately die. But apparently, we didn’t understand it enough to understand that there were certain conditions in which someone would appear to be dead, but not necessarily be dead.

And apparently, it happens that some people were buried alive. And basically, a law was enacted that nobody should be buried for three days because three days would give everyone enough time to actually ascertain that the person is dead.

Yael: That actually leads me to think about Monty Python’s Life of Brian and also Monty Python where they’re satirizing things that went on during the plague and people would go around with wheelbarrows to collect the dead bodies, bring out your dead, and then a guy goes, not dead yet, not dead yet. So. Yes, unfortunately, it’s not something to joke about.

Schwab: So this law presented a problem. Yeah.

Yael: Yeah, so this presented a problem, halachically, to the Jews, and a lot were very angry about it. But Mendelssohn understood that this was an opportunity to endear the Jewish community to whoever passed that law and also to maintain halacha, where he said, it’s not such a big deal. Three days is not such a big deal. This is an opportunity for us to go back to a practice that existed in the time of the Temple that’s little known, where people would be interred, put in a tomb for three days, and then buried or just interred. And because we have that precedent, we can wait three days and be in good standing with the law. And he said that this is something we can tweak, we can change for our civic duty. And that also he probably did not realize at the time, but that is something that is harped on by theologians as to, you know, maybe halacha isn’t static, maybe Jewish law is movable.

Schwab: Although it’s interesting because it sounds like his basis for it was, this is a practice that has changed. We can change it again, and go back to our original practice. As opposed to, here’s something we’ve always done. We can just change that right now.

Yael: And it’s a good example of how he’s misunderstood because he did want to adhere to Jewish law.

Schwab: Right. And he wasn’t saying, let’s do away with Jewish law. He’s like, here’s a halachic way to change the Jewish law, right? Like within the system work to accommodate.

Yael: And he also inherently believed that science aligned with religion. Because he was an Enlightenment thinker. And so he said, he’s like, this is science. It’s science now that we know some people have been buried alive because there are conditions that we don’t understand. And if people can be saved through this adherence to science and through adherence to Jewish law, then obviously that’s the pinnacle.

Schwab: Which also seems like that’s a very important Jewish legal concept, like the idea of potentially saving a life takes precedence over nearly everything. If this is a practice that might save some people. So it seems like waiting to bury someone to confirm that they’re actually dead. If you know that you don’t have the tools to confirm that they’re dead.

Yael: Right. Mendelssohn continues to write, he continues to be a major figure in the Enlightenment, such that he is engaged in correspondence with one of the leaders of the counter-Enlightenment, where they’re arguing about something. And Mendelssohn is carrying the manuscript of this reply to the leader of the counter-Enlightenment on New Year’s Eve. And he got a cold and he died a few days later as a result of delivering this manuscript.

That is in 1786, and so he doesn’t live to see, again, the emancipation of the Jews in Europe, which starts in 1789 in France. So I think that is something that he, I mean, he didn’t know he was going to die, but I think he might have considered a personal failing because it is something that he not only advocated for, but he lived himself. He was a lived example of this. He himself had gotten legal residency in Berlin after winning that essay contest, but what’s really interesting is that after Mendelssohn dies, that status is removed from his wife and children. And then his children, I’m not saying it’s as a result of, you know, losing their legal residency status, but his children do not remain observant Jews. And then by the next generation, there are no Jews among his descendants.

Schwab: Yeah, that’s interesting also because he tried to balance these two things, but his children just gave up on Judaism and completely assimilated living entirely as Germans. But it doesn’t sound like that’s the actual full complex picture because it’s not like they grew up with all the privileges of being German and then said, okay, so what do we need to go back to the shtetl for? After he died, they did not continue to be recognized in that way.

Yael: Right. His own family is indicative of the controversial nature of his life. So Mendelssohn passes away. His ideas live on tremendously til today. Obviously, there’s enough to learn about him that an entire course was offered at your university about him and there.

Schwab: Yeah. I had a copy of Jerusalem that I don’t think that I opened, but hearing you describe it, I’m like, oh, that does sound really interesting. Like religion must inherently be self-motivated and not coerced. That sounds really interesting. I would totally read a book on that topic. I should see if I still have it. Yeah.

Yael: And it’s a very modern idea. It’s an idea that becomes more relevant after the emancipation of the Jews when…

Schwab: Mm-hmm. It feels ahead of its time.

Yael: Right. When you no longer need to live only among Jews, that is when you express true free choice in your religious observance. You know, when you’re growing up in your parent’s home and you don’t have a choice about what you do or what you eat, and then you grow up and you become an adult, and that’s when you, as a human being, decide on how you’re gonna live your life as a religious person or not as a religious person.

Schwab: Yeah, yeah, it feels like it could be such a powerful articulation of Jewish identity and practice in an emancipated era. And, interestingly, he wrote it with, I don’t know if that’s what he was thinking, this is where this is going to go. And I need to explain, you know, how this could work once you’re not living in smaller provincial areas where authority is vested in the local rabbi or a rabbinic court, or he just thought, you know, this is the way it actually should be and then it just happened to happen.

Yael: Two historians that I spoke to about this referred to Mendelssohn as a lightning rod. So he set off a real flurry of ideas. And one of my close friends who is a professor of Jewish history referred to Mendelssohn as enduringly confusing. And I feel that in that his ideas live on. They’re fascinating. I think I could spend months learning about him, but I don’t know that I’d ever come to a place where I don’t find his theology and philosophy confusing.

Schwab: Interesting, because like you said at the beginning, he’s claimed as a forebear for so many different things, but I think he’s also a symbol in a negative way for so many different things. You know, a lot of, I think, movements or denominations might be like, well, that. Where it all went wrong is with Mendelssohn. Mendelssohn’s the beginning of the trouble.

Yael: Exactly, what is his legacy? So now that I’ve rambled on about Mendelssohn for a bit, and you please be honest, don’t lie, do you like Moses Mendelssohn?

Schwab: If this had been the opening of the course, I think that I would have stayed for the whole thing, probably. And I love this frame of, it’s all about his legacy, but his legacy is confusing honestly.

Yael: Very confusing.