What Happened

When Israel declared independence in 1948, the new state decided to absorb Jewish immigrants from around the world. From May 1948 until the end of 1951, more than 650,000 Jews from 70 countries moved to Israel, 200,000 of which came from Arab states who were oppressing the Jewish minority in their countries. Relative to the size of Israel’s population, this move to Israel constituted the “largest single migration of the twentieth century,” says Daniel Gordis of the Shalem College. Israel was a country that lacked the infrastructure for this influx, and Levi Eshkol, then treasurer of the Jewish Agency, lamented to Prime Minister David Ben Gurion that “We don’t even have tents. If they come, they’ll have to live in the street.” Golda Meir went to America on a fundraising mission for these Jewish incomers from Arab states, and as a result of her efforts, prominent historian Martin Gilbert notes that “apartment buildings were built, and new towns, some on the edge of the desert, were set up for the newcomers.”

The Yemenite Jewish community came from poor communities, and were brought to Israel on the famous Operation Magic Carpet, in which one of the Yemenite Jews who was brought to Israel described his first experience on an airplane as the fulfillment of a Biblical prophecy: “It is all written in the Bible, in Isaiah, ‘They shall mount up with wings of eagles.’” Yet the absorption of the Mizrachi Jewish community (Jews from the Arab Muslim world) presented Israel with massive challenges, and they were often placed in transit camps, called ma’abarot. Gordis notes that “these camps created a groundswell of resentment that would foster for decades.”

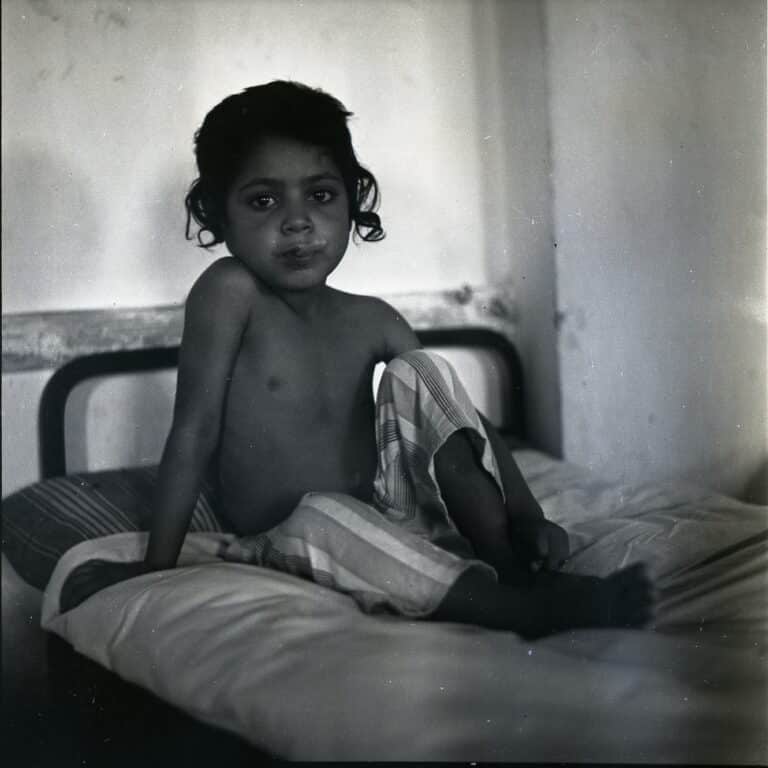

From 1949 to 1954, more than 1,000 Yemenite infants disappeared, and the Israeli government was accused of kidnapping the Yemenite babies and giving them to Ashkenazi families. Given the evidence we have today, the reasons for the disappearances are both complex and in many cases unclear. At the time, overcrowding was a huge issue because of a massive increase in immigration of Mizrahi Jews into the country, and as a result many Yemenite children were transferred from temporary transit camps to a “babies’s house” where their mothers would come to nurse them. If the children became sick, they were taken to hospitals; once parents arrived there, they were sometimes told that their children had died and were buried — without their prior knowledge or permission. There was little to no documentation — not even death certificates — and many parents accepted this tragic fate that their children had apparently undergone.

In 2001, the Cohen-Kedmi government-commissioned investigation concluded that most of the Yemenite babies had died and 56 missing infants were indeed missing, and that there was no evidence of systematic removal of children. Yet Times of Israel reported this past week that there would be a class-action suit, including some of the families whose children disappeared. Attorney Evyatar Katzir said we can’t discuss “statute of limitations when the defendant party continues to mislead the plaintiff.” Two months ago, Justice Minister Ayelet Shaked demanded that the Israel State Archives release hundreds of thousands of unpublished files regarding the Yemenite children.

Why Does This Matter?

- Power of narrative: Whether or not the Israeli government ultimately takes responsibility for this is less important than the reality that Yemenite Israeli families are convinced this took place, and the “mere accusation is a reflection of how life felt to those who became Israel’s underclass in the country’s trying early years,” as Daniel Gordis notes.

- Embrace the national dialogue: This case is part and parcel of the national consciousness of Israel. Being able to assess and understand the multiple perspectives of such a controversial and complicated story in Israel’s history helps connect Jews in the diaspora to real issues still being interrogated by Israelis themselves. To tune into this is, in some ways, to be tuned into a story that is part of the heart and soul of Israeli society.

- Grapple with imperfection: On the one hand, one of the most important aims of Zionism was to develop a forward-facing self-determination secure within itself. On the other hand, some argue that discussing mistakes is fine, but “dirty laundry” should not be aired in front of the rest of the world, who are often ready to take advantage of the errors of the Jewish community.

Diversity of Perspectives within Israel

There have already been so many layers revealed in this story, but there are a multitude of positions within Israeli society that reveal a difference of opinion on both what happened and what should be done as a result. Haaretz reported in 2017 how Rabbi Uzi Meshulam accused the government of deliberately handing over Yemenite children in exchange for money from Ashkenazi adoptees. He threatened bloodshed, was involved in a 7-week standoff with authorities, and served almost six years in prison. Though investigators later found that in fact Jewish parents in America were told they could adopt orphans in exchange for a donation that could help the fledgling state, there remains no proof of an institutional abduction-and-adoption program.

What’s even more fascinating about this part of the chapter is a plot twist. As journalist Ofer Aderet has reported, it turns out dozens of Ashkenazi babies also disappeared, with some vanishing as early as the 1930s and 40s during the British Mandate. Rachel Potter from Ramat Gan recounted that she lost a brother under circumstances similar to the lost Yemenite children and was “angry with with the Ashkenazi establishment just like the Yemenites.” Another Ashkenazi woman who had a similar experience says that this demonstrates that the problem was “not racism of Ashkenazim against Sephardim, but patronizing and arrogance by veterans against new [immigrants].”

As far as next steps, The Jerusalem Post reported in January that the Israeli government passed a bill allowing for the exhumation of Yemenite children’s graves. After public outcry, the government agreed to let families undergo DNA testing to see if their DNA matches that of the remains. Dr. Nurit Bublil, head of the DNA lab where testing will occur, commented, “There are 17 families we have heard about through the media, but there are probably many more – even hundreds. It is hard to imagine that such a horrible thing took place.”

Originally Published Oct 14, 2018 05:20PM EDT