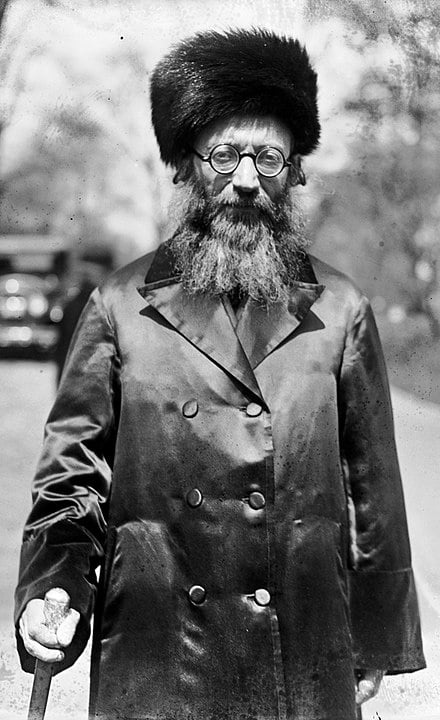

Imagine the highest ranking rabbi in Israel – with a long flowing beard and robes — who not only got along with the most anti-religious Jews he knew, but actually blessed them, and even danced with them.

Well, that rabbi actually existed. His name was Rabbi Abraham Yitzchak Kook and his life was marked by lots of surprising moments in which he reached across the religious divide when others simply would not.

Who was this unique man? And what both enabled and inspired him to build these unlikely bridges, at a critical moment in the Zionist story?

Well, to understand Rav Kook, we’ve got to understand the Jewish world into which he was born—a moment of real crisis.

A Jewish rebellion

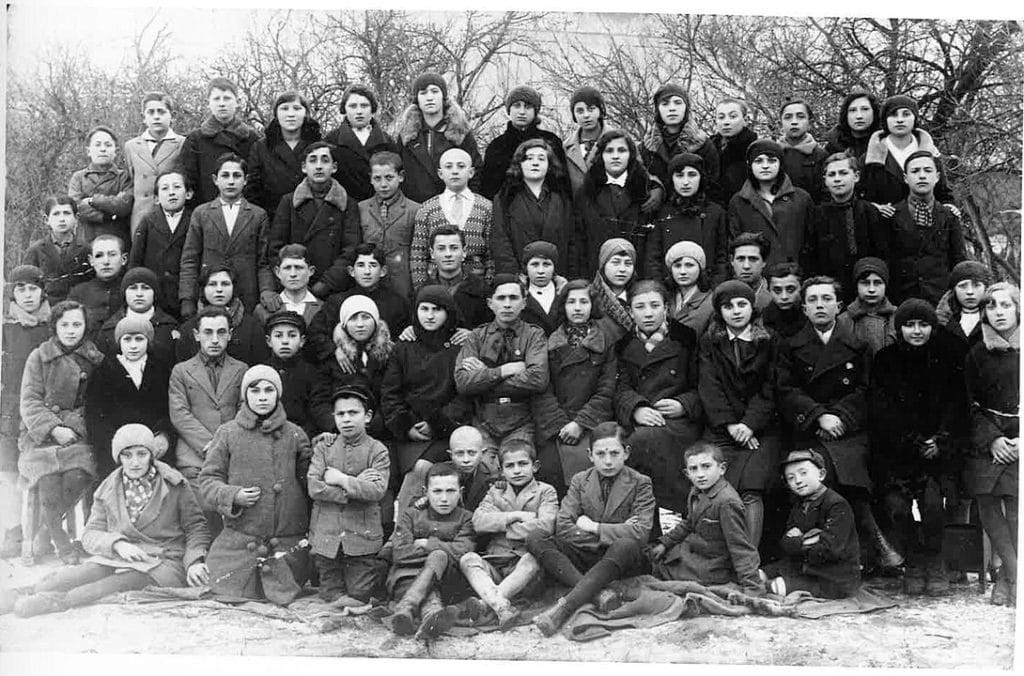

With Jew-hatred, misery, and disappointment growing throughout Europe, some young Jews started to rebel. They insisted that the time to return home and build a Jewish nation– with their own hands – had arrived. The time was now.

These Zionist Chalutzim — the secular pioneers who settled the land of Israel in the early 1900s – were fed up with centuries of Jewish passivity. These self-proclaimed “new Jews” may have seemed like strange bedfellows for Rav Kook. They were fiercely anti-religious. They didn’t observe Shabbat or keep Kosher, and saw the whole Jewish law thing as antiquated.

But in spite of all that, Rav Kook saw the imperative to join hands.

Redeeming the Jewish people, he reasoned, required rebuilding the land of Israel first—and these pioneers shared Rav Kook’s passion for the Holy Land.

That made the seemingly secular chalutzim critical partners in a holy endeavor. “People prove their faith in eternal life by planting,” he said.

Rav Kook’s early life

Rav Kook’s early life was all about Jewish study. Born in Latvia in 1865, he was a Talmudic prodigy. By 19, he was the top student at the yeshiva in Volozhin – the Harvard of Eastern European Jewry.

Beyond his Talmudic wizardry, Kook loved speaking Hebrew, as opposed to the more common Yiddish of the day. Usually, religious Jews suspected Hebrew-speaking Jews of being as one of those secularizing, modernizing “Zionists” – the Jewish nationalists rushing to build a state. But young Abraham Isaac had such a deep, mystical connection to God that no student doubted his piety.

By 23, Kook was serving as a rabbi in Zimel, Lithuania. A year later, his wife died suddenly – and he married his wife’s cousin – at his father-in-law’s request, as that’s what they did in those days. Arriving in 1904 in what was then known as Palestine from Europe, he became the chief rabbi of Jaffa – and the new agricultural settlements popping up around there.

Kook and Herzl

When Theodor Herzl, the founder of modern Zionism, died barely two months later at the age of 44, Rav Kook, as he was known, had a dilemma. Rabbis were not supposed to eulogize secular rebels against Orthodoxy like Herzl. But how could the chief rabbi of Jaffa not honor his people’s desire to honor this great Jewish leader?

The mourners were shocked, and reeling. Herzl had died so young and so many Jews had placed such high hopes in him. As Rav Kook rose at the memorial service, everyone wondered: what would this new rabbi say?

Rav Kook talked about Joseph the dreamer, who, like Herzl was, in many ways, assimilated but devoted to his people. When he rose to power in Egypt, Joseph became a practical leader, the provider of food and of hope to his people and others, practicing universal values.

Kook then talked about Joseph’s brother Judah, who was a more spiritual leader, and more focused on their particular tribe, the Israelites. Jewish history is about the universal and the particular, the body and the soul, Kook said. The Jewish people need a Judah and a Joseph.

Rav Kook not only figured out how to honor the secular Zionist leader, but without ever mentioning Herzl’s name, he gave one of the most famous Bible lessons and memorable non-eulogy eulogies in Jewish history.

Building bridges

After Herzl’s death, the small Jewish community of Palestine remained deeply divided.

The traditionalists, many of whose ancestors had never left the land, were very religious. Some even threatened Rav Kook for being too accommodating to these young pioneering Zionists, returning to revive the Jewish people in their ancient homeland.

Despite the pioneers’ secular rebellion against the dominant Jewish theology of the time, Kook blessed them for redeeming the land and the Jewish people. “That which is holy will become renewed and that which is new will become holy,” he said.

Rav Kook appreciated the holiness in the land in nature’s basic life-cycle – and he saw the Torah – the five Books of Moses – and Jewish law – as filled with opportunities to celebrate those everyday miracles:

in special blessings, in land-based rituals, in the Jewish holidays centered around reaping or harvesting.

The Jewish people’s connection to the Holy Land was historic too.

Rav Kook saw in these young intellectuals-turned-farmers biblical figures: Abraham and Sarah who first reached the land of Israel… Isaac and Rebekah, who prospered in the land of Israel… Moses and Miriam who dreamed of the Land of Israel… King David and King Solomon who ruled the land of Israel… and millions of Jews throughout the millennia who found spiritual meaning by simply living their lives in the land of Israel, the land of the Jewish people, in their homeland, where they belonged.

Rav Kook shared these young history-makers’ hopes and dreams. Life outside of Israel had broken so many Jews, leaving them poor, oppressed, and depressed. Kook understood that the state these young Zionists imagined creating would be a land of Jewish values now being lived daily and of Jewish hopes finally being fulfilled!

Refusing to judge, or fall into extremes, Kook struck an optimistic tone: “The purely righteous do not complain of the dark, but increase the light; they do not complain of evil, but increase justice; they do not complain of heresy, but increase faith; they do not complain of ignorance, but increase wisdom.”

Whereas differences of opinions can lead to disagreements, the challenges of the time needed Jews – of all backgrounds – to rally behind a common cause, a return to Zion.

Rav Kook kept looking for opportunities – to show both the religious Jews and the non-observant Jews that they actually shared a common mission and vision, rooted in the Jewish religion. Visiting the small agricultural village of Poriah in 1913 – founded by pioneers from St Louis, Missouri, and Eastern Europe – Kook proclaimed: “We need to bind together all Jews, from the oldest rabbi of Jerusalem, to the youngest laborer of Poriah.”

He then told a Jewish watchman wearing a Bedouin robe: “Let’s exchange. I’ll take your ‘rabbinical cloak,’ and you’ll take mine.” Celebrating the switch, Kook rejoiced: “So it should also be on the inside — together in our hearts!” With that, Kook, three other rabbis who had joined him, and these gruff pioneers danced into the night.

This kind of bridge-building helped legitimize these rebellious Jews in the eyes of Religious Zionists — while helping legitimize Jewish tradition in the eyes of the Secular Zionists.

Uniting the secular and religious

In the summer of 1914, Rav Kook visited Europe—and found himself stranded when World War I began.

Eventually he served as a rabbi in London, from 1916 to 1919—amid the negotiations and controversy surrounding the Balfour Declaration of November 2, 1917, which promised the Jews a national home.

From there, he urged British Jews to support this breakthrough.

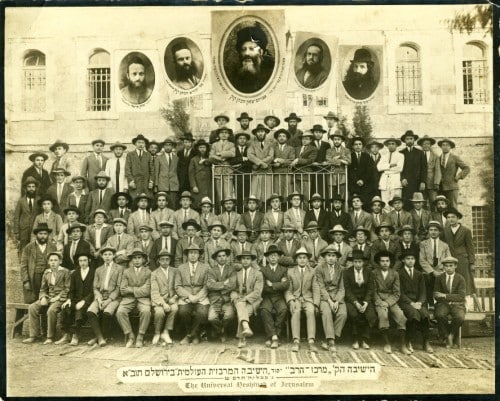

Two years later, in 1919, Rav Kook finally returned to the Holy Land. He was elected to head one of the new rabbinic courts of appeals, becoming, in effect, one of two chief rabbis of Palestine Zionism

Based in Jerusalem, cherished around the world for his scholarship and his humanity, Rav Kook often lectured about Halacha and Aggadah – Jewish law and lore.

In 1920, one of Rav Kook’s students started organizing evening lectures more formally, calling it “Mercaz HaRav” – the Rabbi’s Center. Four years later, “Mercaz HaRav” became a Yeshiva — and it remains one of the most important centers of learning in the Jewish world today.

Over the years, Rav Kook became beloved throughout his homeland as “Palestine’s Jewish Citizen No. 1.” Beyond uniting religious and secular and rival farmer and labor groups, even clashing Jews and Arabs sometimes sat with him, seeking compromise and the way of peace.

When Rav Kook died at the age of 70 in 1935, more than 80,000 people lined the streets of Jerusalem, as a police honor guard escorted his body from the Yeshiva he founded to his resting place on the Mount of Olives. Movie theatres and shops were closed. Representatives from all corners of the Jewish world and from across the Zionist political spectrum came to pay their respects.

To this day, people continue studying Rav Kook’s writings and singing his songs. His words continue shaping Religious Zionism while still inspiring millions to love the land and the people, the world and humanity. In fact, in Israel today, nearly ninety years after his death, whether a self-described atheistic Jew or a Jew with a huge yarmulke, says “HaRav” – THE Rabbi – they mean one person and one person only, “Rav Kook.”