Editor’s note: This is the first article of a two-part series on the history of Jewish Harlem. Stay tuned for part 2 on the Jews of Harlem coming soon.

When you think of the northern Manhattan neighborhood spanning the tip of Central Park to 155th Street, you might picture all that has embodied Harlem history: Duke Ellington’s music, Langston Hughes’ poetry, Malcolm X’s activism, and other rich imprints of Black American culture.

But here’s a lesser-known fact: At the beginning of the 20th century, before the neighborhood became synonymous with jazz and the civil rights movement, Harlem’s Jewish community was the third-largest in the world — just behind Warsaw, Poland, and the Lower East Side. At the community’s peak in 1917, 175,000 Jewish residents lived there.

As a New Yorker interested in Jewish history, I did a deep dive into Harlem’s forgotten Jewish past. Here’s what I learned about the rise of this community, what caused it to dismantle, and the traces of its once-beating heart that remain today.

Why New York’s Jewish immigrants moved uptown

Between 1870 and 1920, over two million Jewish immigrants called New York City their home, with a majority living in crowded tenements below 14th Street.

Life on the Lower East Side was difficult with overcrowded tenements, exposure to disease, and competition for business among many other immigrants — Irish and Italian, for example — who held similar jobs to the Jewish immigrants as peddlers and garment workers.

At the end of the 19th century, some tenements in the 10th Ward, also known as the Jewish Quarter, were demolished to make way for the construction of factories and public parks. Thousands of immigrants were forced to evacuate from their homes and move elsewhere.

Some Jewish immigrants moved to Brownsville, a spacious developing Brooklyn neighborhood, to start a new life. Others moved uptown to the unexpected newest major Jewish enclave of Harlem, with its cheap rent and abundant space.

In 1879, the opening of the Second and Third Avenue elevated trains made it easy for people to escape uptown. The first group of Jews that moved to Harlem were the wealthier German Jews, who settled in Central Harlem.

Then, in 1904, the subway officially opened, bringing Eastern European Jews and a small number of Sephardic Jews en masse to East Harlem. Pretty soon, it became common to see ads for uptown apartments in Yiddish newspapers like The Forward.

“Harlem was a microcosm of an entire Jewish community,” Barry Judelman, a Jewish Harlem tour guide and urban historian, explained in an interview.

“It was a unique combination of Sephardic, Ashkenazi, and German Jews — by the 1890s, these three groups of Jews were living together in Harlem. You didn’t have that anywhere else, not even the Lower East Side,” he added.

The bourgeoisie in the brownstones of Central Harlem

By the turn of the century, Harlem was divided into two Jewish sections defined by wealth and class: Central Harlem (110th Street to 125th Street, Fifth Avenue to Morningside Avenue) and East Harlem (96th Street and the East River to Fifth Avenue up to the Harlem River).

The wealthier German Jews typically worked as clothing manufacturers and shopkeepers and lived in brownstones west of Lexington Avenue, in Central Harlem.

The “bourgeoisie in brownstones” were generally more respected by their non-Jewish German neighbors for the business they brought to Harlem. They sometimes looked down on their Eastern European counterparts for not making enough of an effort to assimilate into American culture.

From the Lower East Side to East Harlem

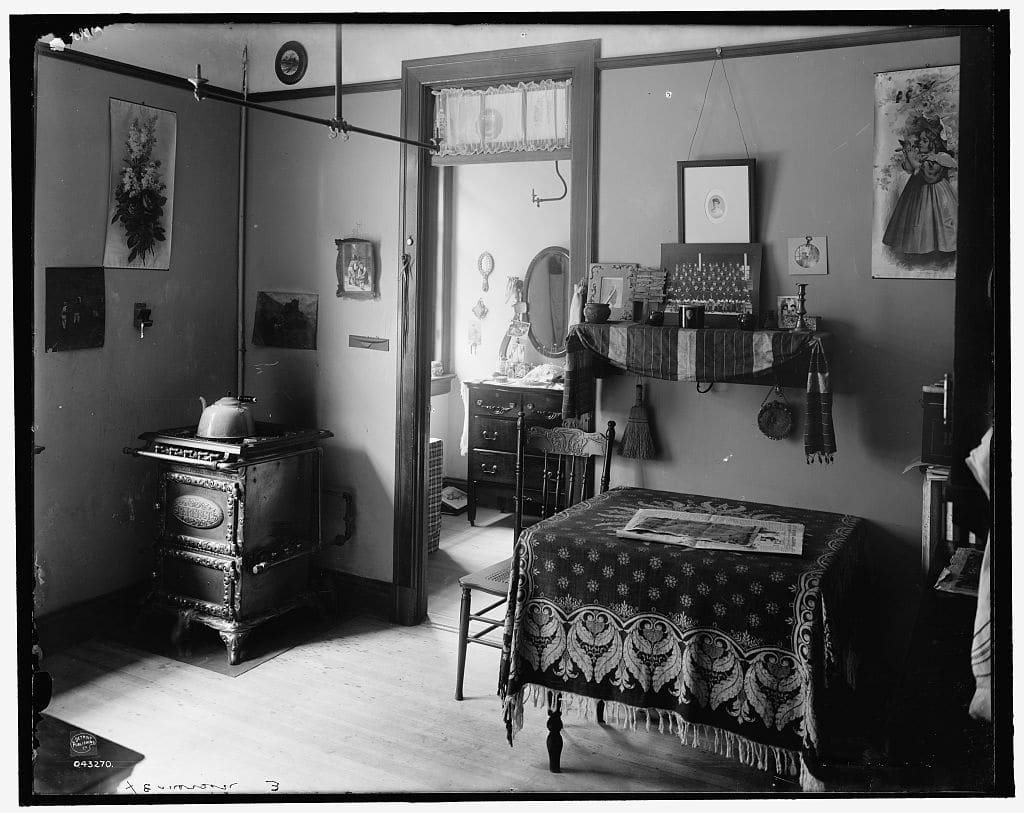

Meanwhile, the Jews from the working class experienced a different reality uptown. They escaped their Lower East Side tenements only to live in new uptown tenements alongside poor Irish and Southern Italian residents, east of Third Avenue.

The living conditions of East Harlem were slightly better than those on the Lower East Side, but the new tenements were still extremely crowded with a density of above 600 people per acre.

These East Harlemites worked as bricklayers, carpenters, and painters, and tried to get local jobs rather than suffer the long subway commute to their former neighborhoods.

The East Harlem Jewish immigrants offered cheaper rates compared to their local counterparts, making it easier for them to get jobs, but their low wages caused tension with their uptown Irish neighbors who held similar roles.

In 1898, David Callanan, president of a local trade union, expressed this sentiment, complaining that “Polish Jews and Hebrew workmen had taken all the work done east of Third Avenue, from the Battery to the Harlem River.”

He further claimed that the Jews’ work was “inferior and they perform much less daily than a first-rate mechanic.” Views like Callanan’s helped spread antisemitism throughout Harlem.

“We draw the line at Hebrews”

As more Jews flocked uptown, the non-Jewish German residents — who had already been living there for decades — did not always welcome their new neighbors. Some existing landowners tried to prevent Jews from moving into the neighborhood, with rental signs declaring, “Keine Juden und keine hunde” (“No Jews and no dogs” in German).

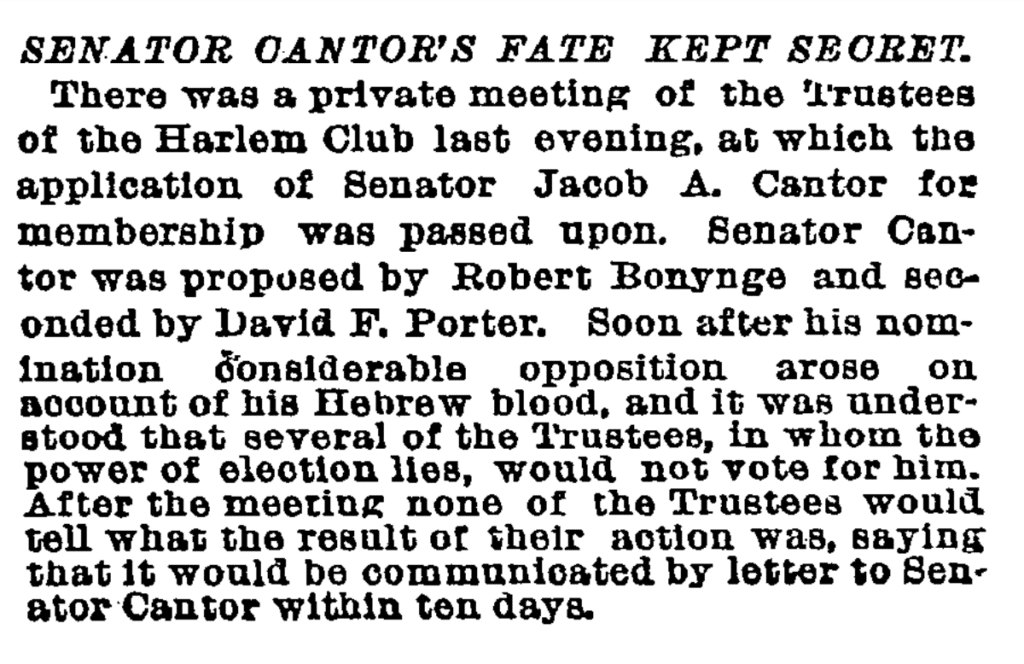

The Harlem Club — an elite meeting place for wealthy, primarily Christian men located at Lenox Avenue and 123rd Street — was another example of blatant antisemitism. In 1889, the club stirred controversy when then-New York state senator Jacob Cantor asked to join and was rejected.

“We draw the line at Hebrews,” a club member bluntly told him. Though some members advocated for Cantor’s admittance, the club never admitted him. Here is the story from The New York Times archives:

The Harlem Club closed its doors in 1907. While some historians believe it closed due to financial reasons, others say its antisemitic policies contributed to its demise, its reputation having been tainted by its bigotry toward Cantor.

Uptown and downtown, Jewish and Italian: Unity over common causes

Despite their differences, uptown and downtown Jews united over growing concerns about the rising costs of living.

Starting in 1902, uptown Jews were inspired by strikes led by downtown Jewish women over the rise of prices of kosher meat. Jews in Harlem organized their own meat boycotts uptown to pressure expensive butchers to lower the cost.

Italians joined their uptown Jewish neighbors in taking to the streets to protest their landlords, who attempted to raise the rents of their shabby old tenements.

For the next four years, Italian and Jewish immigrants would fight in a common cause for better living conditions, often attending the same meetings for socialist groups.

The struggle of maintaining Jewish identity

Another shared concern within the New York Jewish community — uptown and downtown alike — was the lack of Jewish education for their children.

At the turn of the century, many Jewish youth were identifying more as American than Jewish, and families wanted their children to study Torah and Talmud, especially in Harlem where there were not as many Jewish synagogue schools as there were downtown.

To tackle this problem, the Jewish community opened yeshivas throughout Harlem, like Beth Hamidrash Hagadol of Harlem and Beth Knesset of Harlem.

However, like any multifaceted community living in proximity, differences in religious practice often created more problems than solutions. There were often disagreements over how much secular education should be taught and in what language — Yiddish or English.

Despite these educational efforts, because those in the younger generation wanted to integrate into American society, it was often difficult to connect them to what they deemed the “Old World” European ways of their parents.

In order to assimilate more into American culture, the children preferred learning English over their parents’ Yiddish and rejected strict religious observance. In the children’s eyes, distancing from their ancestral history allowed them to adopt a new American identity, which often created tension between them and their parents.

New synagogues for a new community

As more Jewish families filled Harlem apartments, they needed gathering places to pray and celebrate holidays, since the shuls from their former neighborhoods were too far.

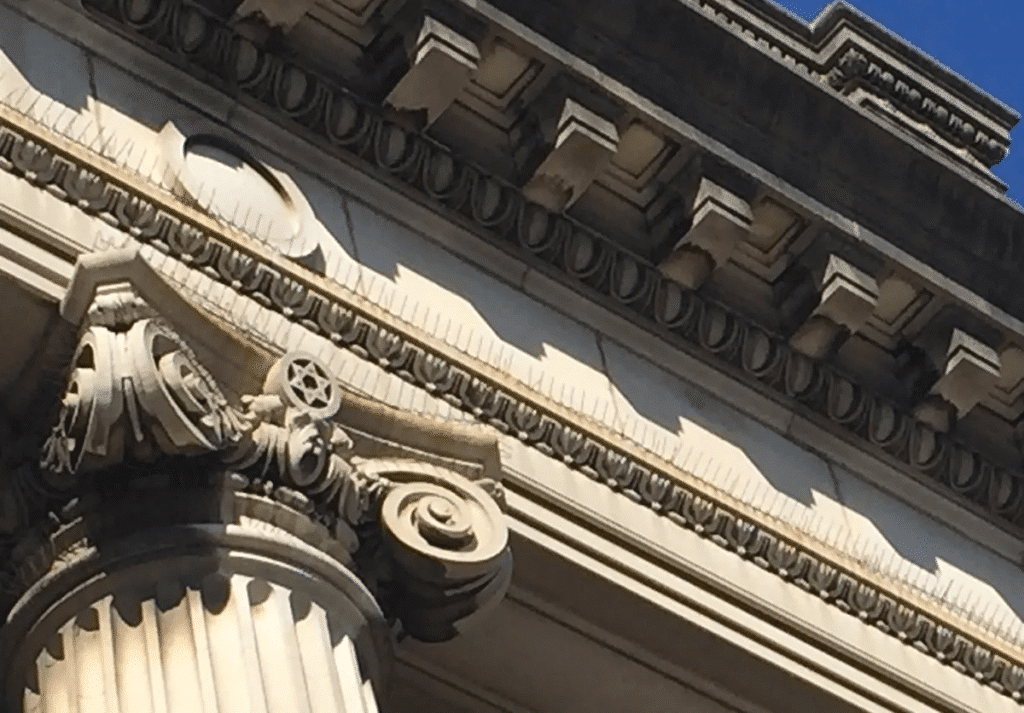

The first synagogue established in Harlem was Yad b’Yad (“Hand in Hand”), created in 1870 by traditionally-observant German Jews. Following some conflict between the traditionalists and Reformists within the congregation, it ultimately became part of the Reform movement and changed its name to Temple Israel of Harlem. In 1907, the Temple moved to a grand limestone synagogue at West 120th Street and Lenox Avenue that held up to 1,500 congregants.

In 1920, Temple Israel moved to the Upper West Side and eventually to the Upper East Side, changing its name to Temple Israel of the City of New York.

The 1907 structure still stands today, operating as Mt. Olivet Baptist Church, but you can still see remnants of the building’s Jewish past in the columns’ Star of David engravings and a motif of two stone tablets containing the Ten Commandments above the Temple’s original organ.

The shul with the pool

Another historical synagogue that originated in Harlem was the Institutional Synagogue. Opened in 1917 by Rabbi Herbert Goldstein in an old theater on West 116th Street, it was known as “the shul with the pool” for having a swimming pool in its basement.

Goldstein’s multipurpose Jewish cultural center was super successful, with more than 3,000 visitors a day and 67 active social clubs. No matter the club, whether it was literary or athletic, every meeting began with words of Torah. Jewish holidays were celebrated here along with Shabbat.

Like Temple Israel, the Institutional Synagogue relocated to the Upper West Side, moving there in 1928. Today, it stands on West 76th Street as the West Side Institutional Synagogue. Sadly, this location does not have a pool.

The end of a Jewish Harlem era

Beginning in 1910, millions of Black Americans fled the South due to unsatisfactory economic opportunities and harsh segregationist laws. The Great Migration brought an influx of Black Americans to various neighborhoods in New York City, including Hell’s Kitchen, San Juan Hill (which is today Lincoln Square), and Harlem.

In 1920, Central Harlem’s population was 33% Black, a number that would jump to 70% by 1930.

As Black and Jewish Harlem residents lived side by side and frequently interacted with each other, both communities had their prejudices. Many Jews were influenced by the general racism of the time — and Black people by the antisemitism, not to mention the resentment they felt toward their landlords who were often Jewish due to economic advancement.

So, why did Jews start to move away from Harlem? “During World War I, the city became very overcrowded as many African-Americans and poor whites working in war industries moved in, and there was deterioration in existing neighborhoods,” Yeshiva University Professor Jeffrey Gurock, author of, “When Harlem Was Jewish 1870-1930,” explained.

“To combat this, New York City’s Board of Estimate offered 10 years free of real estate taxes to anyone who built an apartment building in the outer boroughs or other parts of the City. Jews started moving to whole new areas like Flatbush, Boro Park, and the Grand Concourse,” he added.

Most Jews moved to the Bronx or Brooklyn, while some who had prospered were able to pack their bags and settle in more prestigious neighborhoods like the Upper West Side. By the end of the Jewish Harlem heyday (1870-1920), many synagogues, including Temple Israel and the Institutional Synagogue, had relocated as well.

By the end of the 1920s, only a few thousand Jews remained in Harlem, living in the shadow of what was once a thriving, vibrant Jewish community.

Originally Published Apr 19, 2023 10:25PM EDT