Schwab: Welcome to Jewish History Nerds, where we do exactly what it sounds like, nerd out on awesome stories in Jewish history.

Yael: I’m Yael Steiner. And my childhood dream was to stay in school forever.

Schwab: I’m Jonathan Schwab and I am in school forever.

Yael: Schwab, I’m very sad. This is our last episode of the season.

Schwab: Yeah, I can’t believe we’re here already. This season has flown by so many great stories, so many great topics.

Yael: I’m also very proud of what we’ve done this season. So, while I am sad that this is the last story you’re going to be telling me for a while, it’s overall part of a happy memory, for me.

Schwab: Definitely. And I’m especially glad because I feel like we saved maybe the most interesting one for last.

Yael: That is an exceedingly high bar to clear and I’m going to hold you to it.

Schwab: Okay. So, the character at the center of this topic today is a visionary and a revolutionary. A person who has had a massive impact on Jewish education and Jewish life over the last century. A woman named Sarah Schenirer.

Yael: Not only have I heard of her, I love her. I think she’s super cool. I’m hoping that whatever it is that you have to tell me is not going to take the shine off of that.

Schwab: In my notes specifically was the pun of, of we’re gonna take the shine off of Schenirer.

Yael: Amazing.

Schwab: But not in a sense of like ruining her as a character. But she also was a very real person and who she is as a person, that story sometimes conflicts with the legends about her.

Yael: So, I actually think that her being a real person is going to make me love her more. So, I’m excited.

Schwab: Sure. So, the very basics of her story, she is the founder of a movement called Bais Yaakov, which became a system of schools that during the early 20th century before World War II, became massive. And her last name, it’s like Schenirerer but you kinda just roll the two Rs together. I had to remember exactly how to spell it. Like as, as I spent the last couple of weeks researching it, I got it wrong every single time.

Yael: I think a lot of the people who ever say her name out loud have an accent like mine. So, probably say something like Sarah Schenirer.

Schwab: Schenirer, yes.

Yael: And there’s really only one R.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: Yes, listeners, I’m aware of my accent.

Schwab: (laughs) There is a vowel between those two Rs.

Yael: Not for me.

Schwab: So, let’s start with the very beginning basic biographical sketch of her. Sarah Schenirer is born in 1883 in Krakow, Poland, to a family of Hasidic Jews. The world around her at the time, formal education for young Jewish girls is extremely limited. Formal education for everybody is limited. The literacy rate in Poland, in Russia, where we do have some good data from the early 20th century, the literacy rate in general is less than 50% for most of the population. For Jews, it’s slightly higher. But a lot of that is leaning towards men.

Yael: Do young girls learn how to read Hebrew just so that they can pray or do they not even learn that?

Schwab: Yael, you don’t even know how great of a question that is and how many layers there are to dissect there, like, when young girls are taught, what are they taught? What is the purpose of what they’re taught? What language are they taught in? So, all of those, prior to her starting this entire movement, most girls are taught in the context of their own homes. So there isn’t necessarily a clear curriculum. Prayer, probably something that was not embraced as much as it is today, certainly among Orthodox Jews.

So, teaching young girls Hebrew so that they can pray, not as important as making sure they know how to run a Jewish home, things like that. And if they do pray, they don’t necessarily need to read it, they can memorize the prayers. If they’re learning it directly from members of their family, primarily, an older sister, mother, grandmother, beginning learning all of those things directly by imitation, by memorization.

And there’s this question of language. Schools that were teaching Hebrew language and like the construction of it were more Zionist schools.

Yael: Secular, probably.

Schwab: Exactly. So, the language of instruction, if there is instruction, in Hasidic schools, is Yiddish. And maybe like Polish or Hungarian, something like that, but really not Hebrew. But Sarah Schenirer, great question. Like with all of the education she had, could she read and understand Hebrew as a language?

Yael: So, what was her education?

Schwab: Yeah. She had an eighth-grade education, which is pretty rare at the time. And she also was pretty curious and was somewhat of an autodidact, was able to teach things to herself. So, she had enough skills and enough curiosity that she was able to learn a lot of other things on her own.

She also attended some lectures, where she was able to learn a lot more. If women were interested, they could avail themselves of opportunities like that. A very important thing to note also is that she and her family fled Krakow and Poland during World War I, and were in Vienna, Austria. Whereas Poland was Hasidic and more traditionalist, Vienna resembled more of a German model with an emerging Neoorthodoxy, which was more academic, more inclusive of women, more progressive.

And that’s where in 1914, she goes to synagogue one Shabbat. I think it was Hanukkah, which women going to synagogue wasn’t necessarily something that was practiced widely, certainly in Poland, in Vienna, more so.

It is clear that prior to this, she was already thinking about education for girls. But she is moved by this sermon specifically about the story of Judith, in the story of the Maccabees and Hanukkah, which is something that we did not get a chance to cover in our episode on the Maccabees. And she is moved by the story of a woman who stood up and took action while men were not.

And she decides, “I’m going to move ahead and do something about the problem that is facing our community.” And that’s where she really gets the momentum to start doing something.

Yael: Do we have any indication that this was a problem that other people were thinking about or talking about? Or was this an internal struggle for her, where this was just something that she was grappling with?

Schwab: I love that you asked this question because it’s exactly what I wanted to get to next. It was clear that the whole community was deeply aware of the problem of girls’ education or whether girls’ education is a solution to another problem.

And there were a couple of things going on at the same time. One of them is women, more and more are going into the workforce as jobs are available outside of the home. Again, this is late 1800s, early 1900s. Jobs are available outside the home.

Women could be seamstresses, light laborers, things like that. It becomes necessary because poverty is a deep problem, especially among Polish Jewry. And education sort of becomes really bifurcated where there is more and more a religious educational system for boys and young men. And there’s this huge mismatch then, between what the girls are learning and what the boys are learning.

Even within one family, you could have brothers who are Hasidically educated, spending all of their time learning Jewish texts and girls who are reading the latest French literature, and deeply immersed in the surrounding secular culture of arts and ideas.

Yael: Well, I know that my grandparents, my mother’s parents are both Polish. And my grandmother would often tell my grandfather that his Polish was terrible, because she had public school Polish. So, you know, she lorded that over him a little bit.

Schwab: Yeah. Nice. And the cheder was probably in Yiddish.

Yael: Entirely, Yiddish.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: Yeah. Like he spoke enough Polish to get by.

Schwab: But it wasn’t writing essays.

Yael: They weren’t educated in Polish.

Schwab: Yeah. So, at the same time, there’s also an emerging crisis that it does seem like there are girls and young women who are moving away from religion, from religiosity. This is something that a lot of people are focusing on. It’s clear, they’re like congresses and meetings convened where this is discussed, often primarily by men, as a problem and what are some potential solutions. How do we get all of these young women to be focused more on the traditional Jewish values and stop turning away from that towards the outside secular culture and all of that. There is a problem of racy lifestyles, like what types of professions a lot of these girls and young women were getting into.

And it, it seems like that was a very documented problem, because it’s really talked about in, in the notes from these congresses and meetings and things like that.

Yael: The world’s oldest profession?

Schwab: Yes, that’s the profession we’re, we’re talking about, yeah.

Yael: Interesting. I mean, I can understand why the community would want to steer them away from that.

Schwab: Yes, exactly. So, one of the potential solutions here is creating a system for religious education. Sarah Schenirer was not the first person to think of it. But I don’t think it’s just like she was really lucky, right person, right place, right time. I think there was an element to her, where a lot of other movements had failed or fizzled or just didn’t reach as wide an audience as she did. And part of that, I think, is her incredibly charismatic leadership, just who she was as a person leading this movement.

And I think this is an important element of who she was. I think that she was very politically shrewd about how exactly to position this, because she did need a lot of buy-in from men and from rabbis. So, we know about this from her own diary. She talks to her brother about it. And he’s at first, a little dismissive. He’s like, “Well, getting into women’s education, that’s what the secularists are doing. That’s what the Zionists are doing. Do you wanna really get into like this very divisive, political kind of sphere?”

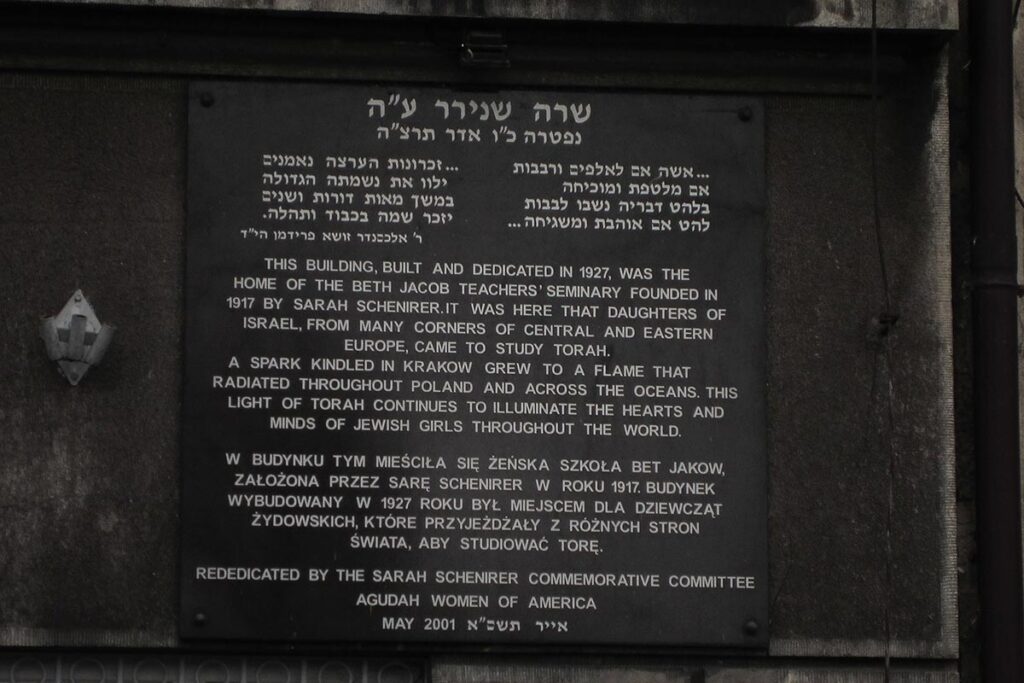

But she does go to the Belzer Rebbe, a large important Hasidic Rebbe to get sort of just like backing for this. And he says to her, Mazal and bracha, or bracha v’hatzlacha, one of those two. But basically, gives his blessing and wishes her good luck on her undertaking. And she starts it as a small number of students in her seamstress studio. It’s probably about two dozen students was her first class. This is in 1917. It went from that one class of about 25 students to, in 1935, where it stood on her death, a network of 220 something schools and 36,000 students and alumni. So a massive, explosive expansion in less than two decades.

Yael: That’s fascinating. And she herself had no formal or maybe even informal background as an educator.

Schwab: Right. She ran a massive network of schools without a master’s in education or an MBA.

Yael: And she had never even been a head counselor at a Jewish summer camp.

Schwab: Well, it becomes, what’s sometimes referred to as a total institution, it’s not just a school that students are at but there’s also all these other parts to it. There’s the supplemental activities through an organization called Bnos. There’s summer camps. There’s a journal. There’s all sorts of things that happen as part of it. And, and she, yeah, I think like, does act in the role of head counselor in a camp.

Yael: So, what is the curriculum, both secular and religious?

Schwab: So, varies by school and over time. And she’s very, very careful about what exactly to teach. So, we have to talk first about, like what are some of the resistances that she potentially faced or actively did face.

There was a long-standing prohibition, tradition, feeling about teaching Torah to girls and young women, based on a Talmudic passage about the equivalence between, teaching your daughter Torah is like teaching her, the word is tiflus. And there’s all sorts of different interpretations, like what exactly does that mean? Is it, you know, no nonsense? Is it a waste of time? Is there some deeper meaning to it? So, for centuries, there had been resistance to formally teaching girls Torah.

And I actually think we should, like read one of the things that she says, which I think, really interestingly, like sort of, has this balance between, what is it that we’re trying to accomplish here? And the question of, is this something that ideally, we should not be doing but we have to do to address the current problem? Or is this, we’re now emerging into a modern age where this is available and this is something that can be done.

So, I’m gonna read a quote, this is a translation. But this is part of an address that she gave in 1929, so it’s already a more mature movement, on the establishment of like a formal women’s organization as part of the Agudat, which is like a larger organization.

But she says, the Orthodox woman has awakened from her long lethargic sleep and begun to organize. It has not been long since we first established the Bnos organization in Poland. And already from the dais of the World Congress, the powerful voice of the religious Jewish woman rings out on the world stage. She is no longer isolated. In every corner of the world, she has close and intimate sisters in spirit.

Yael: Hopefully this is not super controversial to say, to me, it is really reminiscent both of the transcendentalists in mid-19th century United States, like Emerson, Thoreau, thinking about the fulfillment of the individual. And also, the suffragists a bit, women awakening to the fact that they are individuals and that they should have-

Schwab: It sounds feminist.

Yael: … fight an educationist.

Schwab: It sounds modernist. It sounds like it’s about embracing individual identity, all of those things. I wanna read another passage from the same speech.

I know full well that many of our pious Jews will view this with suspicion. We hold sacred the ideal of women’s modesty. And then, she quotes a biblical verse of, she is in the tent, “hinei ba’ohel,” which is referring to the biblical Sarah. No doubt a portion of the community will regard our Congress with suspicion and fear and see it as a deviation, God forbid, from Israel of old. But these same pious Jews need to understand that this conference is a necessary response to the dangers that prey on our sisters from various secularist directions. And then, another biblical quote here, et laasot la’shem. It is time to act in the name of the Lord. From this perspective must our public efforts be understood.

Yael: So, she sounds like she’s a good politician. She’s playing both sides.

Schwab: And I think this is the real question that we’re ultimately not going to be able to answer of like, which one is the real Sarah Schenirer and which one is the thing she’s saying? Like is she a modernist revolutionary feminist who, who wants to awaken people from their slumber?

Or is she really thinking this is all necessary, because we need to protect our daughters and keep them religiously motivated. And we need to focus on this central idea of modesty, which she talks about a lot. Like awakening from the slumber, that’s sort of just like the inspirational thing that maybe is the right thing for some of the students to hear.

The more you dive in to understanding her, through her own words, through her diary, through the way that historians and biographers have looked at her, I have not come up with a clear answer. I think that ultimately, like they’re both true.

Yael: And I think the nice thing for her is that she doesn’t have to answer that question. The bottom line is that this movement takes off very quickly and expands exponentially. And once that happens, she herself, well, A, because she’s no longer alive. But even if she were, even at the time that she was, she cannot have a hand in what happens to every student in the community. So, she creates this platform.

Schwab: Yes.

Yael: And each community is going to use it as a springboard for the outcome that they want.

Schwab: Right.

Yael: And I think that very much has happened. So, the main Bais Yaakov does mean something. But there is a spectrum of Bais Yaakov schools today. And I think that probably happens very quickly, because there was no clear mission statement of the school saying these schools are for the intellectual growth of women or these schools are to protect our women from being corrupted by outside forces.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: Since she didn’t make that clear, every community can kind of do what it wants.

Schwab: Yes, you’re right. Also, it changed very much after her death. And after the Holocaust, prior to that, it was more centrally organized. There was a central office that did, again, probably not exercise a great amount of control over individual schools, especially if they were in more far-flung locations.

And it’s so interesting of just like, what is it that this central office or the journal would publish? And what data do we have from these local schools and what it actually looked like. But it’s even more true, post-holocaust, like there is no central Bais Yaakov office today.

Yael: Interesting. I don’t wanna take us astray because there’s so many things I wanna learn about.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: Why did she call it Bais Yaakov?

Schwab: Great question. And as with everything, there’s like a legendary story to this and like what’s the real actual story? The reference Bais Yaakov is to a biblical verse. And again, she seems like she is very learned and is quoting verses all the time.

As the children of Israel are about to receive the Torah at Sinai, the verse says, Moses goes up to God. And God commands Moses saying, I guess in the Ashkenazi Hasidic tradition, ko somar l’beis yaakov, v’sagid l’bnei yisrael. Like go tell the house of Jacob and the children of Israel. And Rashi, the most famous commentator on the Torah, says, the fact that it specifies Bais Yaakov, the house of Yaakov and Bene Israel, the children of Israel, the first one must be referring to everybody, or the women, and the second is referring to the men.

So, Bais Yaakov is a reference to the giving of Torah to women. For her to come up with that name means she had to have been familiar with this Rashi.

Yael: Which is amazing considering she’s self-educated.

Schwab: Right. There’s also this other legendary piece to it, which is that the right before it says ko tomar, the letters “ko,” kof-hey, the number for that in Hebrew is 25. And that is a reference to her original 25 students.

Yael: That’s a deep cut.

Schwab: Yeah, unclear if that was like a later addition to the legend in some way but you know.

Yael: But she knows what she’s doing, by calling it Bais Yaakov as opposed to, Institute For Women’s Education, she’s endearing herself to the people who need it to be a Torah endeavor.

Schwab: And it claims it when so much legitimacy, because she’s quoting a biblical verse, she’s saying this school is rooted in the Torah. She very often talks about this. This isn’t a new modern thing. This is about getting back to the way things were and we’re losing the ability to transmit the tradition in the home.

Yael: And she’s giving it legitimacy because she’s speaking their language.

Schwab: Yes.

Yael: She’s giving it a name that is drawn from their understanding of Torah. And it makes her seem knowledgeable. It’s kind of like, when I dropped a sports reference like five minutes into a date to make sure that they know that I’m too legit to quit.

Schwab: But exactly like that. You don’t wanna make your reference too intricate because you don’t wanna come off as too knowledgeable, right? You don’t wanna intimidate this person-

Yael: Schwab, welcome to my life.

Schwab: Yeah. (laughs) So, it’s the same thing. Like she is very careful in what references to Torah she makes. She very often avoids actually making legal halachic arguments or justifications for things. She speaks broadly about social ills and what we have to do.

But she doesn’t get into the debate, of like, are we allowed to teach Torah to women or not, that’s for men. That’s for rabbis to decide. She’s not a rabbi. She’s not making those decisions. And we were talking before about curriculum. And I just wanna come back to this because this is another important point. It’s not just about content, it’s very much about feeling and community.

She is devoutly religious in her feeling. As a little girl, she was often given this nickname, little Hasid. There was something just fervently religious about her. And that is the feeling very much in these schools. And a big part of that is not just in, book learning, but singing, praying together, which is like really interesting. The idea that like women were coming together and praying, which is also very fascinating, because I think, what the difference is today.

And whether women’s only prayer spaces, which I think have become a symbol of a much more progressive movements now are less in vogue, in conservative, lower case C, in like Bais Yaakov type environments. But also plays a really big part of this. Like productions, they’re called.

Yael: That is still a huge thing in girls’ schools.

Schwab: It’s a huge thing. Like she saw the potential in that and did something with it. This became something that like girls were incredibly excited about would become a centerpiece of it. Because plays, dramatic arts were something that was becoming increasingly attractive, you know, outside of the Jewish community. And she saw an opportunity to be like, “Well, we can recreate that experience of being in the audience and being on stage and doing all of that but with a Jewish play.”

So, we can have biblical stories. We can have a play about Judith and the story of the Maccabees, like all sorts of great content that we can use to make these very Jewish themed plays and productions.

Yael: Only for women.

Schwab: Okay. So, I wanna talk about this wild anecdote. There’s a scholar named Naomi Seidman. She grew up in the Bais Yaakov movement. That’s not where she is now.

But she wrote a book about Sarah Schenirer. The title of which is Sarah Schenirer and the Bais Yaakov Movement: Revolution in the Name of Tradition, which, perfect name. And she relates this anecdote that she is slightly skeptical about. But the plays were obviously only by and for women.

So, all of the characters in the play are played by women. Even if they have to portray male characters, the girls or the young women would dress up and play male characters on stage.

She’s not skeptical about this, that there were boys who did not have the same opportunities in school who were interested in these plays. And they often had to have some sort of actual, like literal gatekeeping to make sure that boys did not enter these spaces to see the plays.

She has this story, and I don’t think it’s as important like did it happen or didn’t happen, what does it say about the society at the time, about a group of young boys who dressed up as young women so that they could get into this play to see it

Yael: This is a reverse Yentl?

Schwab: But it’s like a whole- because it’s boys dressing as girls to see girls dressing as boys performing on stage.

Yael: Oh, my God, there’s so much there.

Schwab: Yeah, yeah. And it’s also like an interesting reversal of like plays in Shakespeare’s time, where I think like almost exclusively, like male actors were used, young boys were used to play the roles of, of women. And like this was exclusively women played all roles, men and women alike. Yeah.

Yael: So, I have to say, so far, you have not said anything that has made me think she’s less cool. If anything, I think she’s more awesome than I thought she was at the beginning.

Schwab: Yeah, it’s not like she does something that’s like way out of line. It’s just that the vision of who she was historically is a little bit different than the story especially that’s told in this sort of hagiographic style of like she was this incredible angel of a person who never, like did anything other than… like she… it does seem she did travel pretty widely. She talks about this in her diary, like, read literature, go to plays, like… these ideas didn’t come from nowhere.

She got them from the surrounding culture. She was a little more worldly, I think, that is like often told. And I think she was like more shrewd and political than the story is sometimes told about her, as like, she was this incredible idealist. And like she was but she also was very practical and really smart about it.

Yael: I don’t think anyone can question her intentions, even though we don’t 100% know whether or not it was an intellectual awakening or a religious obligation. Either way, her intentions are not nefarious in any way. But I also think that there are a large number of Bais Yaakov families today that wouldn’t necessarily want their daughters to emulate Sarah Schenirer.

Schwab: Yeah. Yeah, like some of those other things that she embraced. Like she was a Zionist. She was openly and validly a Zionist. A lot of Bais Yaakov schools today do not embrace Zionism, do not talk about it. But like, that wasn’t like a little side interest for her, that’s something that she clearly was interested in. She also-

Yael: It also didn’t stop the Belzer Rebbe from endorsing her.

Schwab: Yeah. And it wasn’t clearly wasn’t a central motivation. She wasn’t creating a Zionist network of schools but she was not anti-Zionist. She did not dismiss it. She also was married first.

Yael: … I was just about to ask that.

Schwab: She was married. She was unhappy in her marriage. She was divorced after about three years. And she later did marry again but she… that was already, she was sick and it was in the last few years of her life.

But she’s open about being unhappy in her marriage and getting divorced. And that also, I think, is just like really glossed over in the picture of who she was as a person. She is also really embraced as this mother figure. We know this from diaries of her students who just like revered her not as like a brilliant educator or orator or any of those things, but as like a very caring and doting figure who was like a surrogate mother to many of them.

But she wasn’t a mother herself. She did not have children. And that also like really cuts against a notion of educating girls and young women to be wives and mothers, when it’s clear that was not who she was in her life. Like that was not her central identity.

Yael: I hope this is not a sacrilegious comparison to draw. A little bit, it reminds me of Oprah.

Schwab: Interesting.

Yael: Oprah is this iconic American woman. She has no peer, like literally, like I don’t think you can think of a celebrity who you can put on the same level as Oprah in terms of what she stands for and her influence.

And the fact that she’s able to be this icon without being a wife and mother is fascinating, because she doesn’t get criticized for that. But it’s always something that people kind of talk about slightly on the side.

It’s like, here’s this person who’s telling other people how to live, how to be, how to be educated. But she’s not meeting 100% of our expectations of what a successful ideal woman is supposed to be in our society.

Schwab: Yeah. I think it is an interesting comparison to draw. Oprah isn’t just saying like, here’s what a woman is supposed to be but there’s something that feels also very maternal about her.

Yael: Right.

Schwab: And like Sarah Schenirer is seen as that, is seen as like the mother of not just the movement but like of every single student. She was close with a lot of her students early on. She was not the mother to 36,000 students. She was not that close with all of them.

Yael: So, I have a personal story about Sarah Schenirer. But I don’t wanna take away from any other interesting facts that we might still have left to learn about her.

Schwab: This doesn’t really like fit in anywhere but I think it’s like interesting to note, just as part of her acumen and how she was able to do things. The way that she established schools in a lot of different locations is, she would have a very bright pupil who was ripe to be a really good teacher, who would be very impressive and well-spoken.

And she would travel to a town, a village, a city that did not have a Bais Yaakov along with this rising star. She would meet with the families and leaders in the community, and have everybody be really impressed, by this young woman.

And then, she would say like, “If you want the women of your town to look like this, right now, you can start a Bais Yaakov. And you know what, I have the perfect teacher to be in charge of it. She’ll stay. She’ll be like the head of this thing.” And it seems like that’s a strategy that worked a lot of the time.

She just strategically seemed to really understand how to get buy in and consensus from people, how to create this network. But she also had the total trust of these young women who then would like go to a town they’ve never been before and like devote their lives to her cause, to their cause. They embraced it as part of that.

Schwab: So, one more thing, she works with established men’s organizations like the Agudah, which is a men’s organization. Like the, the passage that we read before is from the establishment of the women’s wing of that, which doesn’t come until 1929.

But this is also really fascinating anecdote and what do we make of this at the laying of the cornerstone of the Krakow Bais Yaakov, the large physical. So, obviously, it’s, you know, it started there. But like the large physical school in 1927, we know that was a large event. And it was very celebratory and there’s a whole ceremony. And there were a number of speakers. But we know from programs printed from contemporary accounts, she did not speak. She did not sit on the dais. She was there, but like was not a central part of the program. And like, what do we make of that? is that she’s playing the political game and knows she shouldn’t be the ones speaking. Did she believe that she shouldn’t be the one speaking? Like what do we make of-

Yael: Really fascinating question.

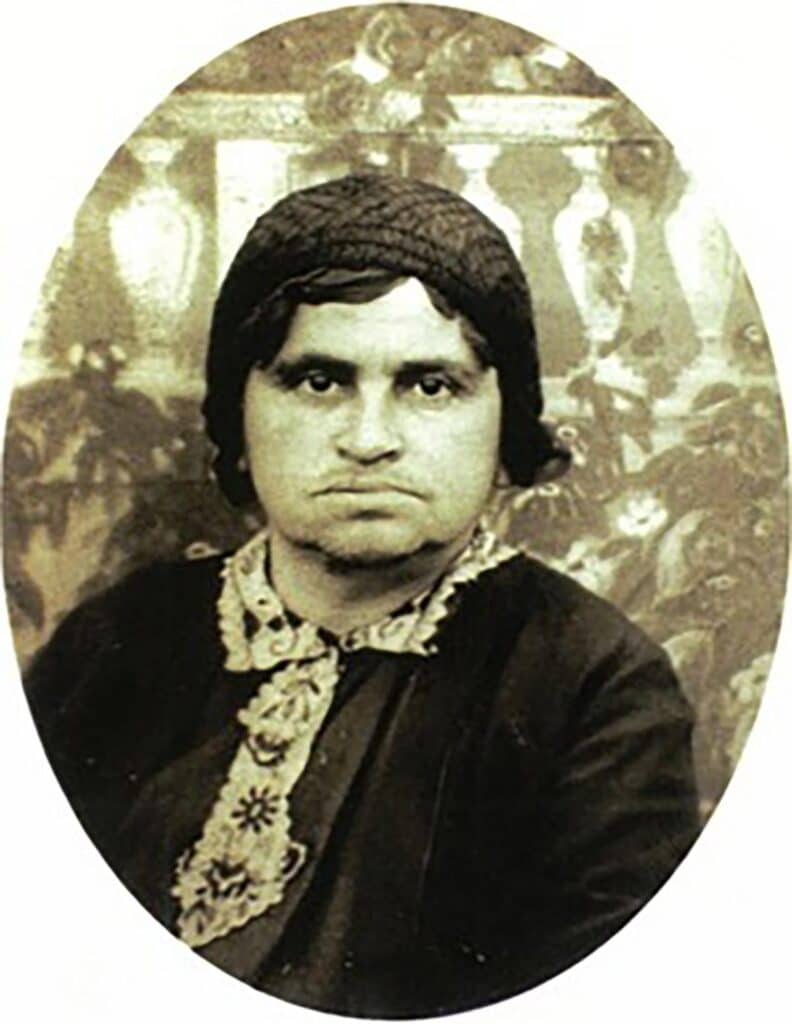

Schwab: the fact that she is like in the background there. It also connects to this thing of her picture. She never wanted her picture published during her lifetime.

Yael: Oh, wow.

Schwab: And is that modesty? Is it that would, in some way, like impede her ability to be a legendary figure? Is it that she did not think of herself as an attractive woman, which we know she talks about that at points in her diary. So, like maybe she didn’t want her picture published because of that.

Actually, we do have pictures of her. But like the image we have of her is very rarely actually connected to literally her image of like what she looked like.

Yael: Is her diary published?

Schwab: So, her diary is published in part… it’s in Polish, originally. In the same volume, Naomi Seidman’s book, which I mentioned before, half of it is sort of a biography of it. And then, half of it is, like the first more full publishing of her diary and selections of her writings and things like that. But I believe the full diary is not yet totally published in English.

Yael: So, I have actually been to the site of the first Bais Yakov in Krakow. And it is very nearby and adjacent to Sarah Schenirer’s grave, which also is on the site of the Plaszow concentration camp, which is the concentration camp that is prominently featured in Schindler’s List. So, there’s a lot going on in that particular geographic corner of Krakow.

Schwab: There’s, there’s always so much to see when you go to Poland, yeah.

Yael: Yeah. So, I went to very, very modern Jewish day schools-

Schwab: Compared to Bais Yaakov.

Yael: Compared to Bais Yaakov.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: And in 12th grade, I went to Poland with my graduating class. And one of the places we went was this site in Krakow of the first Bais Yaakov and Sarah Schenirer’s grave. And one of the educational experiences that was put together for us by an amazing educator named Michal Porath-Zibman, who is a teacher in Israel and a real expert on Sarah Schenirer, actually, was the completion of learning Mishnah by all of the girls in my class and having a siyum at the grave of Sarah Schenirer. And we were each assigned mishnayot to learn. And to no one’s surprise, I waited probably until an hour before the siyum to actually learn mine.

And the passage that had been randomly assigned to me was from Pirkei Avot, which is the ethics of our fathers. It’s three sentences long. And two of the sentences are the sayings that are engraved on each of my grandmother’s tombstones.

Schwab: Wow.

Yael: So, the full Mishnah is asei Toratcha kevah, make your Torah permanent, emor me’at v’asei harbeh, say little and too much. V’havei mikabel et kol adam b’sever panim yafot, greet everyone with a happy countenance. So, my maternal grandmother’s grave says emor me’at v’asei harbeh, speak little and too much. And my paternal grandmother’s gravestone says, V’havei mikabel et kol adam b’sever panim yafot. And the only other sentence in that Mishnah, asei Toratcha kevah, I sort of assigned to Sarah Schenirer as the grandmother of all of Jewish women’s education.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: So, it was a very meaningful experience for me personally.

Schwab: Wow. Thank you for sharing that.

Yael: It’s a super weird story.

Schwab: No, but that’s a cool story. As you said at the beginning, yeah, like I can’t believe this is already the end of season two. We have traveled far and wide and had so many different really interesting stories. A lot in Italy.

Yael: Maybe Unpacked wants to send us on a trip to Italy. Anybody, anybody’s listening?

Schwab: In reviewing what we what we covered this season, I was thinking about like, what is in the water in Italy, like what’s going on?

But also, we have talked about some incredibly fascinating Jewish women this season. And Sarah Schenirer, I think, like brings us to some sort of close on that.

Yael: It’s really nice capstone to think about.

Schwab: Yeah. Just like imagining, you know, the like… the most perfect panel you could ever have. And just if we could get Emma Goldman and Wuhsha the Broker and Sara Copia Sullam and Hannah Szenes. And moderated by Sarah Schenirer. And the topic is what is the role of a Jewish woman.

Yael: And, should that even be a question? Why aren’t we talking about what is the role of a Jewish man?

And I think one of the greatest things about this endeavor for me has been hearing from people with all different types of life experiences about what resonates for them.

And then, of course, also working with Schwab and our amazing producer, Rivky.

Schwab: Yeah. I was gonna say, among all those, those great and inspiring women, I feel really privileged to work with the two women who I work most closely with on this podcast: you, Yael and our producer, Rivky. Two very inspiring Jewish women. And certainly, last but not least, a huge thank you to Dr. Henry Abramson, our education lead, who, he’s always doing a million things (laughs).

Yael: And he knows everything.

Schwab: And he knows so many things. Yeah. But just always a pleasure to talk to and learn from and such a guiding force behind the scenes for all of what we do here.

Yael: Yeah. I aspire one day to have 5% of the knowledge of Jewish history that Henry has available to him at his fingertips at any given time.

Schwab: Yeah, it’s incredible. Yeah. And then, of course, to our audience, we, you know, like-

Yael: We love you.

Schwab: We love you.

Yael: If you’ve enjoyed this season and hopefully season one as well, please bring us into the lives of your loved ones and let us know what you think. We’d love to hear from you, nerds@jewishunpacked.com. I think we nerded out this season. I think we lived up to the new name.

Schwab: Definitely.

Yael: I don’t think anyone’s accusing us of being cool anytime soon.