Today, Israel can be a divisive topic, especially between Black and Jewish Americans.

With some Black Lives Matters activists increasingly using their platform to associate Zionism with colonialism and Apartheid, a discussion has started on how the movement should address its increasingly anti-Zionist and antisemitic leanings. For example, in a column for The Hollywood Reporter, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar said “Recent incidents of anti-Semitic tweets and posts from sports and entertainment celebrities are a very troubling omen for the future of the Black Lives Matter movement, but so too is the shocking lack of massive indignation.”

In fact, division between these communities is not new, as they’ve had their fair share of conflict over the years. Yet, a short time ago, Black and Jewish leadership were united on many fronts – including support for Zionism; so much so that Black leaders like W.E.B. Du Bois and Martin Luther King were vocal supporters of the Jewish State. So how did these two very distinct communities come together in support of the Zionist cause?

“When people criticize Zionists, they mean Jews. You’re talking antisemitism”

Martin Luther King, Jr.

While the Jewish people are a diverse, multi-racial group, for most of American history when we speak about the interactions between Blacks and Jews, we’re speaking about Jews of European descent.

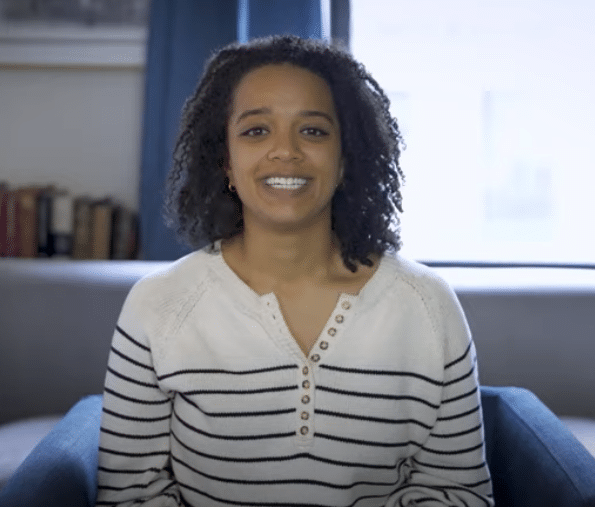

A personal perspective

We spoke to Kylie Unell, a Dean’s Doctoral Fellow at NYU concentrating in Jewish philosophy, about her family’s story. Kylie was named an “aspiring Jewish philosopher” by the New York Jewish Week’s 36 Under 36 and is a writer, podcaster, and the co-producer of the comedy show, Sweepstakes Comedy.

Here’s what she told us:

In the late 19th century, my mom’s side of the family were Ashkenazi Jews living under harsh discrimination in Russia. There was violent, state-sanctioned antisemitism, and Jews were forced to live in what was essentially a giant ghetto known as the Pale of Settlement. Like many Jews, my great-great grandparents escaped persecution and came to America, seeking religious and economic freedom. And yet, my mother’s family immigrated during the height of American antisemitism. Jewish Americans were subjected to physical attacks, discrimination, and vilification in the media.

My father’s side of the family came to America under very different circumstances: they were kidnapped from Africa, brought to America in shackles, and sold into bondage. My dad’s great-great-grandparents were the children of former slaves living in Georgia. Haunted by the horrors of slavery, they were still fighting for their lives and future in the racist South. They, too, faced physical violence, vilification in the media, and discrimination at almost every level, including from the police, the judicial system, banks, and schools.

While my family in Georgia likely didn’t have much interaction with Jews, if any, Blacks and Jews were increasingly crossing paths in other parts of the country. After the Civil War, many Black Americans went North to join established Black communities in urban areas. There they often lived side-by-side with the nearly 3 million Jewish immigrants who came to the US during that time. My mom’s Jewish grandparents came to America and immediately moved to Kansas City, Missouri – where discriminatory housing laws kept Jews, Blacks, and Catholics separate from the White protestants who lived on the other side of town.

Kansas City’s discriminatory laws were not unique. Across the country, Jews and Blacks faced housing discrimination that kept them out of White areas and often threw them together. While most people are familiar with Jim Crow and “Whites Only” establishments that barred Black people, many people don’t know about antisemitic housing and job discrimination. Even affluent Jews faced discrimination from country clubs, private beaches, and whole neighborhoods that wouldn’t let them in because of their ethnicity.

Of course, despite the antisemitism, my Jewish family and other Jewish Americans had many advantages. For example, it was easy for shops to identify Blacks and kick them out of their stores – while most Jews could get by “passing” as White. Secondly, while both communities faced poverty, Jews benefited from greater access to financial systems, such as loans and the abundance of Jewish philanthropies supporting the needs of their community.

An additional advantage was that thousands of years of Jewish communal life had bred strong Jewish leadership that led a well-organized social and political machine. Some Jews brought this organizational experience over to the Black community as early supporters of the National Urban League and the NAACP, whose boards and leadership included Jewish activists. Many of the lawsuits these Black institutions brought to court were argued by Jewish lawyers.

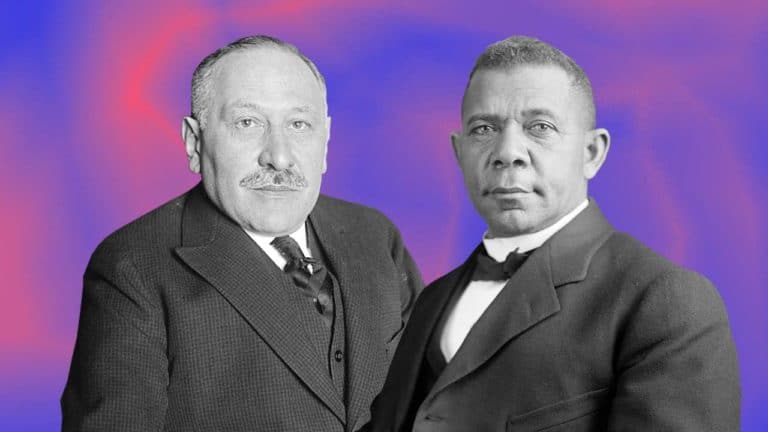

One remarkable example of cooperation between Jews and Blacks began in 1910 – when Julius Rosenwald, the Jewish philanthropist and president of the Sears, Roebuck, and Company department stores, read a book by Booker T. Washington, an educator who started his life as a slave but eventually built up the illustrious Tuskeegee Institute in Alabama. The two men became friends and spent two decades building 5,000 shops, homes for teachers, and schools that educated more than 600,000 Black children in what became known as the Rosenwald School Project. Washington went on to speak at synagogues around the country. He invited rabbis to be guest speakers at the Tuskegee Institute – and Jews served on the board.

Despite such meaningful cooperation, there were also significant divisions. Within a few years of my mom’s family moving to Kansas, one of the most divisive events between the communities was playing out just a short drive away from my family in Georgia.

In 1913, in Atlanta, a Jewish man, Leo Frank, was convicted of murdering a White girl based on the testimony of a Black man, Jim Conley. That testimony, and the resulting media storm, drove a wedge between Blacks and Jews-who-suspected Conley was not only lying but was the actual killer. National attention on the case brought out tremendous antisemitism in both White and Black communities. And while it’s now clear that Frank was not actually guilty, that didn’t stop a White mob from breaking into the local jail, kidnapping Frank, and lynching him. It was in the aftermath of this event that the Anti-Defamation League was formed “to stop the defamation of the Jewish people, and to secure justice and fair treatment to all.”

Despite the ADL’s universal approach – and the partnerships of those like Rosenwald and Washington – Jews and Black didn’t interact much. Socially, they came from distinct cultures. Politically, the groups did not see a reason to join forces, and Jewish groups were hesitant to make common cause with a group as publicly reviled as the Black community.

With limited interaction, both communities had their prejudices. Many Jews were influenced by the general racism of the time – and Black people by the antisemitism. Blacks mostly only knew about Jews from the Bible: they were God’s chosen people, a nation formed in slavery and blamed for killing Jesus. Black opinions of Jews could hinge on which of those ideas was more prominent in their consciousness. Economic differences also created divisions. Jewish economic advancement and subsequent investment in urban real estate meant that many Black tenants came to know Jews as their bosses and landlords. These factors, among others, helped cultivate antisemitism in the Black community. One early voice of such antisemitism was Marcus Garvey, a Black Nationalist, who claimed Jews were attempting to destroy the Black American population.

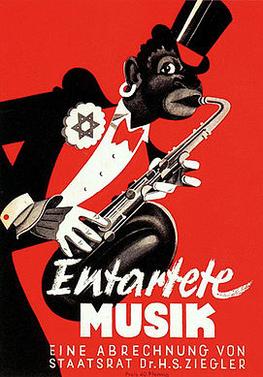

But, in the 1930s and 40s, the divisions between these two communities, largely fell by the wayside with the rise of a new force in the world – that convinced both communities that they needed to unite.

The late 1930s not only saw the rise of Nazism in Europe, but also the rise of American groups that supported the Nazis and fascism — groups composed of the same racists the Black community had been fighting for a long time. The growth of Nazism made it clear to American Jews that their political isolation undermined their efforts to save Europe’s Jews and fight the rise of domestic antisemitism. The Holocaust was a turning point that compelled many more Jews and Jewish institutions to recognize the common cause they had with the Black community in the fight against bigotry.

Black organizations were eager to join forces with Jewish organizations, not just to advance their own political interests, and not just because the Nazis were horribly racist. Black Americans, like most Americans, were horrified by the Holocaust, spurring many to realize that Jews were also a vulnerable minority that needed protection and support. Prominent Black activists and organizations began advocating for Jewish interests, including the Jewish right to self-determination in their historic homeland – aka Zionism.

In the wake of WWII, the NAACP was outspoken for the rights of refugees and the freedom of movement for minorities – including Jews headed to the Jewish homeland. Black scholar and diplomat Ralphe Bunche led the UN commission charged with setting up the young Jewish state. He was hailed as a hero by the Jewish community, yet a year later, W.E.B. Du Bois criticized him for not sufficiently championing Jewish interests in the Holy Land.

Ultimately, the horrors of the Holocaust pushed Jewish and Black Americans to acknowledge that they not only shared a common enemy, but they also shared a common vision for the future: a world devoid of hatred and discrimination, where people of all races and creeds can live in freedom and fulfill their potential. This was a critical value to the Zionist vision and the nascent Jewish State. The relationships developed during the first half of the 20th century created the foundations of significant partnerships during the Civil Rights Movement — partnerships that can continue to serve as inspiration for both communities even today.

Originally Published Feb 2, 2022 12:02AM EST