Remember May 2021? Gorgeous weather. Covid vaccines. Deadly violence in the Middle East.

“One of the most significant evenings of tension that Jerusalem has seen in several years. According to the Palestinian Red Crescent, more than 200 people were injured…”

“The hostilities in Israel continuing for yet another day as terrorist organization Hamas is showing no sign of slowing its rocket barrage on Israeli civilians.”

“With the weight of the Israeli Air Force on top of them, there is nowhere safe to run…”

Depressing as this sounds, it got worse. As buildings in Gaza collapsed and Israeli families fled rocket fire, for the first time in Israel’s history as a state, citizen turned against citizen. In the mixed cities of Akko and Lod, Arabs set fire to synagogues. Jews pulled Arabs out of their cars and beat them. And across the globe, a corresponding surge in antisemitic attacks on Jews. Men with megaphones shouting “Israelis kill children!” before assaulting diners at a kosher restaurant. A brick thrown through the window of a kosher pizzeria in Manhattan. Swastikas carved into synagogue doors. Not to mention the barrage of online hatred or the beatings and harassment of Jews in the street.

The world watched in horror as the death toll mounted in the Middle East. As Jews across the world became targets and scapegoats. The ugliness seemed to come out of nowhere. Status quo one day. Everything on fire the next.

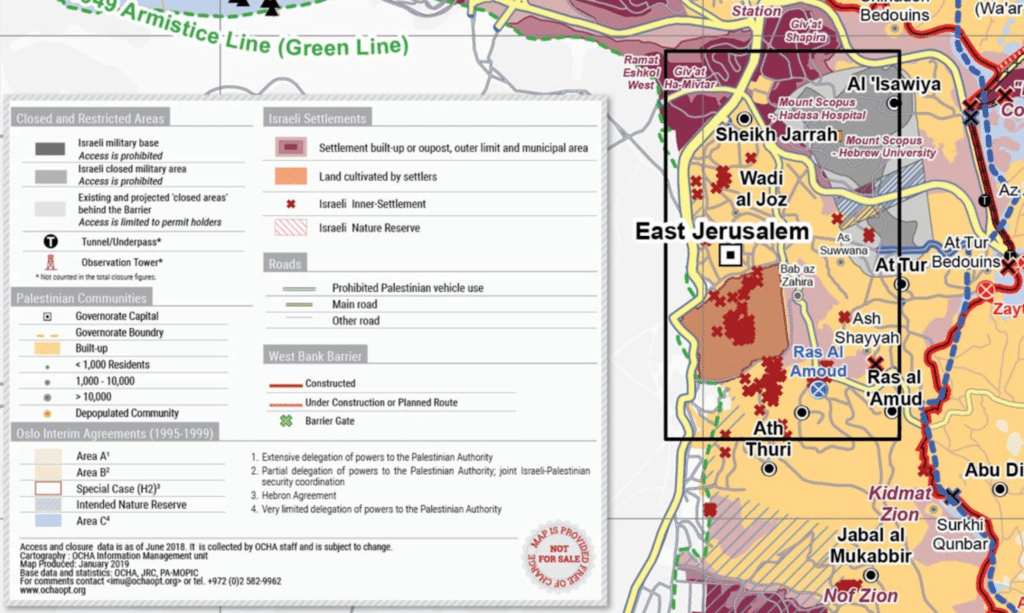

But in truth, this kind of violence doesn’t erupt out of nowhere. The tensions that led to May 2021 had been simmering for over ten years. And slowly, international news organizations began to devote headlines to the root cause of the conflict: a tiny, sleepy neighborhood that few outside Israel had ever even heard of: the neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah. Depending on who you ask, the story of Sheikh Jarrah is either a routine property dispute gone terribly wrong, or part of a policy of systematic ethnic cleansing that continues to inflame Middle East tensions today. But if you’re asking me? I think it’s more nuanced than either of those takes.

So how did a tiny East Jerusalem neighborhood become the wellspring of so much conflict? The answer — as usual — lies a century in the past.

Before Jerusalem was divided into an “East” and a “West,” or eastERN and westERN, before the city was a symbol of nationalist aspirations, Sheikh Jarrah was merely a neighborhood. A neighborhood named for Hussam al-Din al-Jarrahi, Saladin’s personal physician, who is buried nearby. Sheikh is an honorific in Arabic, kind of like “Lord,” while jarrah means healer – kind of an ironic name for a neighborhood at the heart of so much conflict.

But Saladin’s doctor was not the only famous figure interred in this ancient ground. Because literally touching Sheikh Jarrah is a compound that’s been sacred to Jews since a thousand years before the rise of Islam. Inside are the remains of the Jewish High Priest Shimon HaTzaddik, or Simon the Just. (Man, these names! Hussam the Healer, Simon the Just — so much cooler than Noam the Podcaster.)

Anyway, like Hussam al-Din al-Jarrahi, Shimon HaTzaddik is all over the historical record. He was a Jewish High Priest, which had been a pretty important job that involved sacred rituals and sacrifices in the Jewish Holy Temple. Now, the Temple hasn’t existed since 70 C.E. But it certainly existed in Shimon’s day, and he occupies a place of some importance in Jewish lore for rebuilding the walls of Jerusalem, repairing and expanding the Holy Temple, and greeting Alexander the Great when he popped by Judea – so yeah, he was kind of a big deal.

It’s not uncommon for the tombs of religious figures to become sites of pilgrimage. But I’m particularly charmed by something our writer, Adi Elbaz told me. She read in historian Simon Sebag-Montefiore’s book, “Jerusalem: A Biography,” that, apparently, when the Ottomans controlled Jerusalem — so, for the 400 years between the 16th and 20th centuries — the tomb was the site of a yearly “Jewish picnic” celebrated by Muslims, Christians, and Jews. Which I find kind of adorable.

But there’s a little fly in the ointment here. Because according to historians and scholars, including Montefiore himself, the tomb doesn’t actually belong to Shimon HaTzaddik. An ancient inscription suggests that in fact, it’s the final resting place of a Roman woman named Julia Sabina. I’m not formally a historian or an archaeologist, so I can’t comment on whether or not they’re right. But I do think that in some ways, it doesn’t matter whose bones are interred in that grave. In my opinion, the identity of whoever is in there – whether Shimon, Julia or anyone else – doesn’t cancel out the hundreds of years of pilgrimage and general coexistence.

Honestly, if anything, the confusion over who is actually in the tomb perfectly symbolizes the importance of myth. And if the word “myth” sounds derogatory to you, go back and listen to other seasons. I’m not criticizing the role of myth, or saying that myths are somehow illegitimate. Quite the opposite – so many of our convictions, as humans, rest on myths. And so the identity of whoever is in that tomb matters less, in the end, than everything they’ve come to symbolize. Keep that in mind as we continue in this episode.

So: we’ve got a neighborhood that’s home to two important tombs in a region that’s changed hands, often violently, a couple dozen times. If you’d asked your average Jerusalemite three hundred years ago who the neighborhood belonged to, my guess is that he or she would either say “to the people who live there” or they’d mumble something about the Ottomans.

But things began to change in the late 1800s, as the Ottoman Empire began its slow and torturous decline. In 1876, two Jewish religious trusts decided to actually buy the tomb and its surrounding land and establish a Jewish neighborhood known as – wait for it – Shimon HaTzadik. I know, clever. Soon, a second neighborhood, Nahalat Shimon, or Shimon’s Inheritance, sprang up nearby.

Today, these two areas are considered a part of the larger neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah, so just to be clear, when we talk about Sheikh Jarrah, we’re including Shimon HaTzaddik and Nahalat Shimon. According to Ottoman census data, by 1905, the neighborhood was home to 167 Muslim families, 97 Jewish families, and six Christian families – a pretty diverse neighborhood.

But this multiculturalism didn’t last long once war erupted in 1948. After over a year of fighting between the newly-established IDF and various Arab forces (see our Season 4 Israel@75 mini-series for more about the war), the Old City – and the area we now know as “East Jerusalem” – fell under Jordanian control.

Expulsion is an ugly fact of war. Jordan expelled Jews from this area, and that’s a fact. And, Palestinians too lost their homes, when they fled or were expelled from places like Haifa or the Galilee. And that’s important, not because I’m interested in litigating who quote, unquote, “suffered” more or whose tragedies are more quote, unquote, “valid.” But the displacement of Palestinians in 1948 is an integral part of what happened next in Sheikh Jarrah. Because in 1956 – eight years later – the Jordanian government in tandem with the UN decided to resettle 28 displaced Palestinian families in the neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah.

As refugees, these Palestinians became the responsibility of UNRWA, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East. So UNRWA and Jordan hatched a plan. Jordan would lease out a significant chunk of property in Sheikh Jarrah where UNRWA could build 28 brand new homes. At the end of three years, the Jordanian government was to sign over property rights, and these resettled Palestinian families would officially own their properties, meaning they’d no longer be considered refugees.

But here’s the rub. Jordan never quite got around to transferring ownership to those 28 families. Plus, they were dealing with the condemnation of the international community, which was less than impressed by this whole annexation thing. See, according to the UN, annexing a territory is pretty much totally illegal. Keep that in mind as this story continues.

Nine years later, Jordan found an unlikely solution to its annexation blues. Because in June of 1967, Israel and its neighbors fought yet another war. And over the course of six dramatic days, Israel routed Jordanian, Egyptian, and Syrian forces from Jerusalem, Gaza, the Sinai, and the Golan Heights. And that meant that East Jerusalem – and the 44,000 Palestinians who lived there at the time – was now under Israeli control.

And this is where things start to get messy. (Because they were so simple ’til now, right?) It took thirteen years for Israel to officially annex East Jerusalem. And spoiler alert? The international community still didn’t like annexation.

But international censure had nothing on the frustration of East Jerusalem’s 44,000 Palestinians, who suddenly found themselves in a very complicated position. Because if you’re a Palestinian, your status and your citizenship depend on where you live.

You live within Israel proper? Great! You’re an Israeli! You’ve got an Israeli passport! You get to vote in as many elections as you want! In fact, 20% of Israelis are, in fact, Palestinians, though not all of them identify this way. Some call themselves Israeli-Palestinians, some Israeli-Arabs, some just Israelis, some Palestinian citizens of Israel… identity, man. Complicated.

But say you’re a Palestinian living in East Jerusalem – a territory that both Jordan and Israel had officially annexed. So are you a Jordanian citizen? An Israeli?

Well, it’s complicated. Because in 1967, Israel offered the Palestinian population a chance to apply for citizenship. But in the words of the UN’s Secretary-General’s representative, the Arabs of East Jerusalem “…were opposed to civil incorporation into the Israeli State system.”

In other words: thanks but no thanks, Israel!

So all of a sudden, Israel had a population of Palestinians living under its control who were, in some cases, hostile to Israel and citizens of an enemy country. Things only got messier in 1980, when Israel passed a law officially annexing East Jerusalem – a law that the rest of the world refused to recognize. Once again, the government offered the residents of East Jerusalem an opportunity to apply for citizenship. And once again, the vast majority of East Jerusalem’s Palestinians declined.

But here’s where it gets really crazy.

Jordan and the Palestinians haven’t historically had a great relationship. By the time the Oslo Accords were signed in 1993, the Jordanians were in the process of revoking citizenship from East Jerusalem’s Palestinians. Some East Jerusalem Palestinians are still technically Jordanian citizens, and all have travel documents that allow them to cross into Jordan. But the majority of East Jerusalem’s 350,000-ish Palestinians are technically not citizens of any country, making them officially stateless. (And yes, if you’re paying attention, that is pretty explosive population growth.)

Is your head spinning yet? Mine is.

Now. Let’s talk about the third group of Palestinians. Because remember, after ’67, Israel controlled East Jerusalem and the West Bank. But today, most West Bank Palestinians live under the control of the Palestinian Authority – not Israel. And according to the PA’s citizenship laws, PA citizens must either be born or live in a region under PA control. And the PA does not control East Jerusalem. So while the Arab residents of East Jerusalem can technically vote in PA elections, their votes won’t impact their lives in any material way, since the PA has no authority in their neighborhoods.

Okay. So then why would East Jerusalem’s Palestinians decline to become Israeli citizens? Why refuse citizenship?

Well, put yourself in their shoes for a minute.

Imagine that for decades, you’ve been living under the control of someone you consider an enemy. Your relatives in the West Bank and Gaza are suffering. For whatever reason, and, blame whoever you want. Your Arab friends or family members within Israel technically have the same rights as Jewish Israelis, but report discrimination, high rates of crime, and structural inequity. And if you feel, in your heart, that the country that controls your home is an occupier, why would you agree to become a citizen? Why would you swear an oath of allegiance to a country that you personally believe should not exist?

To be clear, I don’t want to speak for every Palestinian in East Jerusalem. No community is a monolith. But broadly, that’s the gist of the sentiment. It’s easy for me to say that I disagree – and hey, by the way, I disagree. It’s a little harder, but I think more important, for me to truly sympathize. Because most Palestinians in East Jerusalem aren’t evil monsters who refuse citizenship because they hate all Israelis and want them to die. They’re the descendants of people who have fled or been expelled, who have lost their homes, and who have never, ever known what it’s like to govern themselves.

So, let’s summarize. Unlike the 1.5 million Arab citizens of Israel, who have all the same legal rights as Jews, East Jerusalemites have a special status as quote, unquote “residents.” They pay Israeli taxes and are subject to Israeli laws. They get Israeli social and health benefits and use Israeli infrastructure, like the post office or the light rail. And depending on where they work or even where they live, they might often rub shoulders with Jewish Israelis. But the similarities end there.

Unlike full Israeli citizens, like I said, the residents of East Jerusalem can’t vote in national elections. They can run and vote in municipal and local elections only – though they cannot run for mayor. They can’t serve on the executive board of Jerusalem’s Development Authority, which makes important decisions about urban planning – like where roads will go, and where and which buildings will get built. They don’t hold Israeli passports, which means their opportunities for travel are fairly limited. But perhaps most importantly, their residency status is conditional. And it must be continually “proven” and documented, which – if you’ve ever dealt with Israeli authorities or stood in line at an Israeli post office – you know is a bureaucratic nightmare.

So it’s not a huge surprise that in recent years, an increasing number of East Jerusalem’s Palestinians have been applying for Israeli citizenship. But even that has been a tough process. It can take up to three years just to get an appointment to have your case heard. It can take another four years for the government to come to a decision. And huge numbers of people end up being rejected, sometimes for seemingly arbitrary reasons. Put all of this together, and you can see why the residents of East Jerusalem feel that the odds are stacked against them. That they are subject to a government that is neither for them nor by them.

And that they are caught between three countries that either don’t really want them or can’t offer them anything. Israel and Jordan aren’t offering full citizenship, and the PA is corrupt and ineffective.

All of which brings the following statistic into sobering relief. Because in June 2022, the Palestine Center for Public Opinion conducted a poll in East Jerusalem, asking questions like “Which citizenship would you most want to have?” Guess what they chose. Guess. Okay, I’ll tell you.

Forty-eight percent chose Israel.

Forty-three percent chose the independent and theoretical Palestinian state.

Nine percent chose Jordan.

That’s a wild stat that absolutely blew my mind. Because all the research we did for this episode indicated that, well, East Jerusalem’s Palestinians are deeply unhappy. I watched so many videos and read so many articles with words like “settler colonialism” and “apartheid” and “illegal occupation authorities” that I kind of forgot a really important fact. And that is: we’re all just people. The Palestinians of East Jerusalem are sick of being caught in between multiple identities, sick of being used as a political football. And if it came down to it, roughly half would choose to become Israelis, not because they’re in love with Israel, but because they’re practical.

My guess is that they’ve seen the changes in Israeli society since 1967 and 1981, when they were offered the opportunity to apply for citizenship. They’ve watched Palestinian leadership splinter into increasingly corrupt, ineffectual, and violent factions. And — like most people around the world — they’ve decided that safety and prosperity and opportunity in the here and now might just be more important than some far-off ideal of a state that might never come to fruition.

Keep that in mind. Because it makes the story I’m about to tell you that much sadder.

Remember like 10 minutes ago, before this deep dive on the status of East Jerusalem’s Palestinians, when I told you about the sleepy East Jerusalem neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah? Well, by the 1970s, it wasn’t so sleepy anymore. In fact, it would soon become a microcosm of the entire Arab-Israeli conflict.

The Jewish residents of East Jerusalem, including Sheikh Jarrah, were expelled from their homes in the wake of the 1948 war. For 19 years, they waited for the day they could take back their property. That day came in 1967, when Israel won East Jerusalem from the Jordanians. Now, as I mentioned, the Jordanians had resettled 28 Palestinian families in Sheikh Jarrah and promised them the property rights to their land. But the Jordanian government never transferred ownership of the land to these Palestinian families.

So who owns Sheikh Jarrah and the properties within it? Is it the two Jewish trusts who bought land there all the way back in the 1870s? The Jordanians, who conquered the land in ’48? The Israelis, who conquered it from Jordan in ’67? Or the Palestinian families who were resettled in Sheikh Jarrah by the Jordanians and the UN, but who never received the property rights they were promised? You see what I mean about this neighborhood acting as a microcosm of the entire conflict?

To make matters even more complicated, in the immediate aftermath of the Six Day War, the Israeli government passed a law entitling anyone who had been expelled by Jordan to reclaim their property — if they could prove ownership. Now, I want to be clear. The text of the law doesn’t mention Jews or Palestinians. Technically, if a Palestinian could prove that they lost their home to Jordanian forces in 1948, they’d be eligible to sue for it, too, and theoretically, they could get it back from whoever lives there now.

But let’s be real here. Jordan didn’t expel Palestinians in 1948, and the law only applies to people who’d been expelled by Jordanian forces. So while the text of the law isn’t explicitly discriminatory, its application could be. Because no equivalent law exists for people who were displaced by the IDF. In other words, the Jews – or Jewish organizations – of Jerusalem can sue to get property back that belonged to them before the war. Palestinians – whether they’re Israeli citizens or East Jerusalem residents – can not.

So those two Jewish trusts who bought land in Sheikh Jarrah back in the 1870s? Well, they were still around a hundred years later. And under the text of the law, they had the right to try and get their property back. But though they had lost their property to the Jordanians, their issue wasn’t with the government of Jordan. It was with the Palestinian families living in Sheikh Jarrah.

Sometimes, I hate politics. Actually, often I hate politics. Because if anyone did anything wrong, it was the Jordanian government that expelled Jews from their homes back in 1948. But the Jordanians aren’t suffering under this lawsuit. The Palestinian families — who were themselves displaced in the war — are the ones that have to deal with the consequences. I’m not saying that the Jewish trusts don’t have a legal case, by the way. I’m just commenting that sometimes, everything’s the worst. (You’re welcome for that nuanced political analysis!) More seriously: I’d hope we can agree that evicting families feels a little… icky. Maybe a lot icky.

So: in 1972, the Palestinian families who had been living in this area got a surprising notice in the mail. They were behind on rent. They could make their checks payable to these two Jewish trusts. What the heck? they thought. They’d been resettled here by UNRWA and Jordan. They didn’t know who had been living here before. And they didn’t think they had to pay rent.

So they didn’t.

A decade later, the Jewish trusts — which had since registered the land as theirs, as was their right under the law — took 23 Palestinian families to court for their refusal to pay the rent. As you might imagine, the case was contentious. Plus, as always, the context was complicated. These court cases began in the 80s and continued into the 1990s, at the height of the Oslo Agreements. For a time, it seemed as though the Palestinians might actually be on the road to getting their own state. And if that happened, who knew? With enough international pressure, East Jerusalem could potentially have become this new state’s capital, I don’t know. But these Jewish trusts were not going to let that happen without a fight. The more Jews lived in East Jerusalem, the stronger the Israelis’ leverage to keep Jerusalem unified – i.e., entirely under Jewish control.

I know this whole thing sounds cynical. And I hate being cynical. Cynicism is corrosive. But I also think it’s honest. This is the Middle East. Everyone has an ulterior motive. Anything can be weaponized, including our histories, our competing narratives. This is Yishai Fleisher, one of the Jews who lives in East Jerusalem: “One component of this building, these buildings, these six buildings, is that they are a physical structure in Eastern Jerusalem with a flag on top that says the Jews are here. Israel’s here.”

And you know what? He isn’t wrong. The Jewish people have always lived in Jerusalem. Jerusalem has always been the beating heart of the Jewish people, the seat of our government, the symbol of our peoplehood. So I have enormous empathy for Fleisher’s perspective here, and for other Jews like him. And I have the same empathy for his Palestinian neighbors. Because this feels like a zero-sum game. The narrative that wins the day does so at the expense of the other.

To quote the words of Palestinian intellectual Sari Nusseibeh I love quoting him: “Our respective absolute rights — the historic right of the Jews to their ancestral homeland, and the Palestinian rights to the country robbed from them — are fundamentally in conflict, and mutually exclusive. The more historical justice each side demands, the less their national interests get served. Justice and interests fall into conflict.” That’s really wise.

But the Israeli Supreme Court refused to accept this line of thinking. So in 1982, they came up with a compromise. The Palestinian families could stay on the land as protected tenants, provided they paid rent and signed an agreement acknowledging that the land belonged to Jews. The families signed the agreement. But that wasn’t the end of the story. In 1993, one of the trusts took the families to court again, claiming they hadn’t paid their rent in years. In response, the Palestinian families claimed that yeah, maybe they hadn’t paid, but that’s because the agreements they’d signed were worthless. They’d signed under duress, thanks to the threat of eviction. And they were taking a stand! As the legal owners of the land, they would not be paying rent.

It’s genuinely hard to overstate how long and torturous these proceedings were, dragging from 1993 to 2008. Claims. Counterclaims. Appeals. New cases. We’ve linked a few resources for you in the show notes if you’re my kind of nerd, who wants to delve super deep into the minutiae of it all. But what you need to know is this.

In 2001, Israeli courts ruled in favor of the trusts who claimed ownership of the land. Yes: it took eight years for them to decide that the Palestinian tenants were squatting illegally on that land that did not belong to them without paying rent. It took another seven years for the first Palestinian family to be evicted from their home.

Think about that. This property dispute has been going on since the 1980s, since before I was born! In the meantime, people are living their lives. These Palestinian families had kids, who grew up, got married, had kids of their own. Today, multiple generations live in one house. Grandmas and grandpas. Parents. Kids who grow up knowing only that they can’t trust that they’ll have a roof over their heads in a month or a year.

Again, we can believe that the Jewish trusts had a legal right to the land — and still believe that these Palestinian families got a really raw deal here. And in fact, lots of people in Israel did believe that. In the wake of the evictions, Jewish Israelis began to protest in solidarity with the Palestinians of Sheikh Jarrah. Here’s Sara Benninga, a chief architect of the protests, speaking about her experiences as a leader in the solidarity movement. “Every week we kept marching. Every time, we grew a little bigger. We started with 30, then 50, then 70, by the fourth week we had 120 people.”

By 2011, Sheikh Jarrah was not just a rallying cry for a handful of Palestinian families, but a cherished cause of the Israeli left. And for a little while, it seemed as though Jewish solidarity might actually change things for these Palestinian families.

Here’s Nasser, one of Sara’s Palestinian friends who had been evicted, speaking in Hebrew: “I really hope that very soon, we will be returned to our home, and that the settlers will leave, and we can go back to living how we did before the evictions and the courts. And I would very much like to wish the Jewish people a Shana Tova and a happy holiday.”

It seems hopeful, almost. A moment of shared humanity. Of two peoples accepting each other’s narratives, each other’s legitimacy. All the while, the beleaguered families of Sheikh Jarrah battled the Israeli legal bureaucracy for over a decade. And it seemed as though this unpleasant status quo would simply go on forever, with neither side advancing their cause.

Until May of 2021, when the Israeli Supreme Court was set to hand down a ruling on the status of Sheikh Jarrah’s residents. This was it, finally. No one knew exactly what the ruling would be. But they suspected that it wouldn’t go in favor of the Palestinians — and during Ramadan. So after nearly a decade of relative quiet, protests erupted in the neighborhood. And they soon spread to the rest of Jerusalem.

Which brings us back to the start of this episode.

“The demonstrations spread to other parts of the city, including the Al-Aqsa Mosque, one of the holiest sites in Islam. Heavy-handed policing fueled anger as tensions escalated. Many see this as the spark that triggered one of the deadliest episodes of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in recent history.”

And how did things spiral so quickly out of control? Because Hamas — the terrorist group that runs Gaza — got involved. And there’s nothing they appreciate more than the opportunity to sow chaos. Hamas supporters thronged to the mosque, shouting “Bomb Tel Aviv!” The terrorist group then issued an ultimatum: withdraw from Al-Aqsa and Sheikh Jarrah by 6pm, or else. The state of Israel declined to dignify this ultimatum with a response. And so both Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad began to unleash a barrage.

[CLIP] “Tonight in Tel Aviv, images that change everything in an escalation that has already spiraled so fast. Israel’s missile defense systems lighting up the sky as they try to intercept incoming Hamas rockets. 130 of them were fired from Gaza in one barrage. Flights at the international airport were urgently suspended and diverted…”

And, as you could probably predict, Israel wasn’t gonna let that stand. Within hours, the IDF began strafing Gaza.

Desperate to calm the tensions, Israel’s Supreme Court delayed the rulings as the violence escalated. But it was too late. The war of May 2021 lasted only 11 days. But it claimed 14 Israeli lives, killed 3 Thai and Indian workers who had come to Israel in search of economic opportunity, and claimed the lives of 284 Palestinian civilians, 1 Lebanese protestor, 1 Arab-Israeli, and between 80 and 200 Hamas operatives. Now by the way, I hate doing the numbers game, the numbers thing, because it’s so important to mention that so many Palestinians that are killed are there and are killed because Hamas fires rockets from places where there are so many Palestinian civilians. And that’s an important point.

And all because of a court case from the 80s.

Two months later, in August of 2021, the Israeli Supreme Court handed down its ruling. They’d cancel all the eviction orders if the Palestinian tenants would recognize the Jewish ownership of the land and pay a symbolic rent of roughly $420 a year, which entitled at least one member of each family to a lifetime of protected tenancy. The families appealed, and in October of that year, the court came back with a similar compromise. The Jewish trust also promised not to seek additional legal action for the next 15 years.

The Palestinian families were split. Half refused outright. The other half considered it. And in the meantime, Hamas and the PA turned up the pressure, calling on all the families to resist the temptation to end this battle and simply live in their homes.

The families refused the compromise. And in March 2022, the Israeli Supreme Court ruled that at least four Palestinian families from Sheikh Jarrah could not be forcibly evicted until it decided once and for all who owns the land. Since then, these Palestinian families have been counter-suing, claiming that the land is in fact theirs. While this battle stretches on, Palestinian families are safe from eviction. But I don’t think that anyone – Jewish or Palestinian – truly believes that this matter is settled. Because as we’ve said, it’s not really about who owns Sheikh Jarrah, is it? These court cases are an apt distillation of the two competing narratives that govern this city, this country, this land. And that doesn’t seem like a conflict that’s going to be settled any time soon.

So that’s the story of Sheikh Jarrah, and here are your five fast facts.

- Sheikh Jarrah is a small East Jerusalem neighborhood whose existence dates back til at least the 12th century CE. The area we now call Sheikh Jarrah also includes a Jewish quarter called Shimon HaTzadik, where Jews have maintained a documented presence for thousands of years.

- In 1872, two Jewish organizations jointly bought the tomb and the land that surrounds it. But after the war of 1948, the Jewish residents were expelled or fled. By the mid-1950s, Jordanian and UNRWA moved in Palestinian refugees who they promised would receive property rights to the land. That never happened.

- Things changed again in 1967, when East Jerusalem came under Israeli control. The neighborhood’s Palestinian population declined the Israeli government’s offer to apply for citizenship, and today, 95% of East Jerusalemites hold an awkward “residential status,” somewhere between full citizens and guests who can be deported.

- A 1970 Israeli law says that Jewish Israelis have the right to reclaim the property they lost in ’47 and ’48. In 1972, the Jewish organization that bought Shimon HaTzaddik’s tomb 100 years before started demanding rent from the Palestinian families. They’ve been duking it out ever since.

- Multiple Arab families have been evicted from their homes since 2008. The situation escalated dramatically in May of 2021, inflaming a short but nasty conflict between the IDF and Hamas – and between Jewish and Arab Israelis. In late 2022, the Israeli Supreme Court ruled that there would be no further evictions until the matter of ownership is settled – which might not happen in our lifetimes.

Those are the — complicated! — facts, but here’s one enduring lesson as I see it.

Ever heard of the literary term synecdoche? Basically, synecdoche is a figure of speech in which the part is substituted for the whole. Like, when I asked for my wife Raizie’s hand in marriage, I wasn’t just asking for her hand, you know? The hand is synecdoche for the whole person. Well, in my opinion, Sheikh Jarrah is synecdoche for the whole Palestinian-Israeli conflict. It’s a tidy encapsulation of a much larger history of property dispute and conflict and anger and mutual, competing claims – to the land, to legitimacy, to justice.

If Sheikh Jarrah is a real estate dispute, then so is the entire Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Which is why, though we just spent 20 minutes detailing the background to the unglamorous, prosaic details of property deeds and ownership disputes, at the end of the day, I don’t know if they actually matter when it comes to shaping public opinion. Or, more accurately, it’s why different people can look at the exact same facts and come to wildly different conclusions. Because as with the entire conflict, we’re wired to shape the facts into a narrative that supports our prior biases and convictions.

We believe things because we want to believe them. Because they resonate on an emotional level. And nothing could be more emotional than Sheikh Jarrah — a neighborhood that represents two ancient and competing claims.

Bias, emotion, irrationality, seeing what we want to see, seeing only the things that confirm the beliefs we already hold — it’s all a part of human nature.

Kenneth Stern — the American Jewish Committee’s antisemitism expert, and yes, that’s an awesome job — observed in his book The Conflict Over the Conflict: The Israel/Palestine Campus Debate that this bias creeps in even when we’re trying to become better-informed. I hate the terms “pro-Israel” or “pro-Palestinian,” but in this case, they’re useful: “pro-Israel” folks are more likely to see the news as biased against them and favorable towards the other side. But “Pro-Palestinian” folks report the exact same phenomenon, but in the opposite direction. In short, both sides see the exact same articles, listen to the same podcasts, and watch the same TV reports… and believe the reporting is stacked against them.

And this is reflected in the language that we use.

Are we fighting over Sheikh Jarrah, the 12th-century neighborhood named for Hussam al-Din al-Jarrahi? Or are we fighting over Shimon HaTzaddik, whose existence predates Islam by nearly a thousand years? Is this a matter of ethnic cleansing, or a question of restoring the neighborhood, even symbolically, to its oldest remaining owners? Are Israelis “settlers,” who have come to dispossess Palestinians and steal their homes? Or are they descendants of the neighborhood’s native inhabitants?

The way we answer those questions speaks volumes about how we see the conflict.

So that’s not why I’m telling you the story of Sheikh Jarrah. I’m not trying to change your mind, or convince you of anything! What I’m actually trying to do is create empathy. Behind every statistic, every Ottoman census, every property deed, every legal dispute is a human story. And if we don’t recognize that, we’re doomed.

So I want to end, aptly, with a teaching from Shimon HaTzaddik. I’m quoting here: “Shimon HaTzadik would say, the world stands on three things. Torah, the priestly sacrifices of the Temple, and g’milut hasadim.” G’milut Hasadim is one of those cool Hebrew concepts that lacks a direct or easy translation. In English, it’s most often defined as lovingkindness — one word. And I think, honestly and truly, that g’milut hasadim is our only way out of this. We have to extend lovingkindess to each other. We have to see our neighbors’ stories as legitimate. We have to empathize with the kids who have grown up under threat of eviction. With the families who have spent decades battling for their right to live in their homes. True, Jerusalem is a small city. But its history is long, and its story is big enough for two nations to tell.