Schwab: Welcome to Jewish History Nerds, where we do exactly what it sounds like, nerd out on awesome stories in Jewish history.

Yael: I’m Yael Steiner, and my childhood dream was to stay in school forever.

Schwab: I’m Schwab, and I am in school forever.

Yael: Oh, wow. No first name today, Schwab.

Schwab: Do I usually say my first name?

Yael: You’re getting, like, intimate with our listeners.

Schwab: I am. It’s more familiar and comfortable when I go just by my last name.

Yael: Amazing.

Schwab: What are we gonna be talking about today, Yael?

Yael: Have you ever heard of a literary salon?

Schwab: Sure. People get together and read and talk about different ideas, I wanna say probably dress up nicely and, and eat fancy foods also.

Yael: Very similar to The Finer Things Club on The Office.

Schwab: A hundred percent.

Yael: So a literary salon is, as you mentioned, usually hosted in someone’s home. And the intellectuals of the area often gather, painters, artists, poets, authors, to talk about the high-minded ideas of the day. And today, we’re gonna be talking about a remarkable Jewish woman, Sarra Copia Sullam, who was born in Venice in 1590 and hosted one of the first literary salons that we’re aware of in modern history. And through her participation in the intellectual community of Venice, found herself embroiled in several scandals over the course of her life.

Schwab: It’s such a change of pace that we’re gonna talk about someone involved in art because we usually talk about business, politics, antisemitism or war.

Yael: So the antisemitism here is a bit more muted. And even I can’t believe I’m saying that because she did live in the Venetian ghetto. Jews were ghettoized. So when I say that the antisemitism was muted, I mean that it wasn’t violent.

Schwab: It was just like the normal part of her everyday life as it was in, what was it, 16th Italy for everybody.

Yael: Exactly. It was the everyday antisemitism that they had grown used to, unfortunately.

Schwab: It’s that everyday antisemitism that you gotta watch out for.

Yael: The black-tie antisemitism we can handle. But the contempo-casual is a little more dangerous.

Schwab: (laughs) How’d she get into this literary scene?

Yael: Great question. She came from a relatively upper middle-class, almost affluent family in the Venetian ghetto. Towards the end of the 16th century, moneylending was winding down as the primary profession for Jews in Venice. Because, the Christians lifted their own ban on moneylending.

Schwab: So Christians were allowed to lend money to each other, which meant that it was no longer monopolized by the Jews.

Yael: Yes. Absolutely. And this was also around the time when Shakespeare was writing “Merchant of Venice,” so it’s sort of ironic that one of the most famous stories about Jewish moneylending was written around the time that this phenomenon was really waning. That being said, her father and her husband had both made a nice, tidy sum in the moneylending business. So she was affluent and she was actually encouraged by her father, who perhaps saw in her some intellectual stirrings, a brightness of intellect, maybe saw some potential in her and encouraged her to start this literary salon.

Schwab: Huh.

Yael: And I think it’s important to note that this salon was attended by a variety of Venetians both Jewish and non-Jewish. Because although the Jews of Venice were ghettoized, the ghetto was only closed at night. The Jews were free to come and go and visitors were free to come and go during the day. So-

Schwab: So this salon was during the day when people were allowed to come?

Yael: Presumably.

Schwab: I kind of just always imagined if people are gonna get together and talk about the arts or something that it would be at night. But I guess I have to change my mental image of this thing and imagine this… the sun shining in through the windows.

Yael: That’s because you’re not a lady of leisure.

Schwab: (laughs)

Yael: Or a man of leisure.

Schwab: Right.

Yael: Both can be people of leisure.

Schwab: Uh-huh.

Yael: I really loved learning about her. I think I have a lot of soft spots for this story for a variety of reasons. One is that I did not realize that women at that time in that place, particularly Jewish women, were so well-educated, that they could be the hostesses of these high-level discussions and that their homes could be the epicenter of high culture.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: I would love to be in the position to be someone who sits at home and welcomes very smart people to talk about really cool things. Uh, it sounds like a lovely existence.

Schwab: What are we doing right now?

Yael: Very fair, but it would be nice if we were also, you know, drinking tea and eating scones. Maybe we could get that together for the next recording session.

Schwab: For the next episode. Yeah.

Yael: We probably should get some snacks. There are two other soft spots that I actually have here. One is, I traveled to Italy in 2018 by myself, and I was fortunate enough to spend a Shabbat in Venice. And I stayed not in the ghetto, but very close to the Venetian ghetto and went to services on Friday night that were held outside in the plaza of the Venetian ghetto. And I remember, during that experience, feeling so fortunate as a Jew that I could pray so openly, that we were dozens of people sitting outside, singing songs, welcoming Shabbat in a place that was once very much an epicenter of persecution for Jews. And there we were, celebrating and singing freely, and it was very meaningful to me. So to read and research this story about the Venetian ghetto brought me back to that feeling. And the other is that one of the scandals that we’re going to talk about is her exchange of letters with a Genoese monk who had written a play that she had read and loved and their epistolary friendship which is something that I’ve always been very drawn to. I love books and movies that have men and women corresponding about literature. That’s kinda my guilty pleasure.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: So I did like a lot of things about this.

Schwab: You’re drawn to the idea, not personally drawn to epistolary correspondences with Genoese monks.

Yael: Correct. I don’t currently have one of those relationships. That’s not to say one won’t develop.

Schwab: I like the currently. I did at one time have a pen pal with this Italian priest.

Yael: I did have a pen pal named Eunice in third grade. Total side note.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: So let’s get into some of the scandals that she is well known for. She is married off quite young to a gentleman named Jacob Sullam. It’s not clear what the emotional connection, if any, was between them. We know that they stayed married for a while. Unfortunately they lost a small child. And she also suffered, we know, at least one miscarriage. So they did not have any surviving children. Other than that, we don’t know much about their marriage and their relationship. But she was married.

Schwab: Uh-huh.

Yael: She reads a play called L’Ester in the year 1618 which is about Queen Esther, the heroine of the Purim story.

Schwab: Cool.

Yael: And it is written by this Genoese monk named Ansaldo Cebà. She becomes obsessed with this piece of literature. She loves it. And she starts writing to the man who wrote it, Ansaldo.

Schwab: These are, like, fan letters or these are-

Yael: These are fan letters to a, certainly by 16th and 17th century standards, salacious degree.

Schwab: Oh. Oh, okay. So it’s not just “Wow, I love this play and this scene,” but it’s more like, “You must be so talented, and I’m really enjoying reading your work,” type of stuff.

Yael: So she sends him a letter that says that she loves his work and she sleeps with the book under her pillow every night.

Schwab: She really loves his work. Okay.

Yael: And that she carries it with her everywhere.

Schwab: Wow.

Yael: I don’t know if that was her first letter to him or one of the firsts, but later on in their correspondence, which consists of dozens of letters, he tells her that he sleeps with her portrait under his pillow at night.

Schwab: Okay. But I’m just checking. He’s a monk, right?

Yael: Yes, he is a monk and he lives-

Schwab: So he’s not really supposed to be doing whatever this is.

Yael: Correct. They wrote each other some fairly salacious letters. Not all of their letters were love letters. But some were. And I’m just gonna read you some of the letters. We have his letters to her. It’s not clear that any of her letters to him were salvaged, but he actually published his letters to her. He wasn’t keeping this under wraps.

Schwab: Yeah. And the sending the portrait thing, like, even in our modern times, sending a picture of yourself is very clearly a romantic probably-

Yael: Yeah. Early modern sexting.

Schwab: Yeah. It’s a propositional thing to do, I guess is a good way to put it.

Yael: So here is some language from one of his letters to her. “Oh, how many things does the love that you bear my verses make you say, and how many does the craving that I have for your salvation make me say? I admit that because of it, I also feel incited by a certain passion that perchance is not so criminal. But for me, it is so suspect that if you were where I am, you would recognize the consequences of my servitude, yet not see the features of my face.” And while, you know, we would have to parse-

Schwab: it’s too bad this is a podcast because I wish that people could see the features on my face right now reacting to everything you just read.

Yael: And then he goes on, to talk about not only how much he loves her and loves her mind, but that he wants her to convert to Christianity.

Schwab: Okay. Now, I was gonna say because, um, in the first line there, there was sometimes about her salvation and, like, what does he mean? Salvation sounds pretty convert-y to me.

Yael: Yes. So he ends the letter, Ansaldo Cebà, your ladyship’s most indebted servant. But at the same time, he is basically telling her that she’s in the wrong. So he’s negging her a lot.

Schwab: Hmm. (laughs)

Yael: He says, “I disagree with you and will always disagree with you as far as the profession of Judaism is concerned. But for the rest, I make you and will always make you as much a mistress of my will as you may be of yours.”

Schwab: Wow. Okay. This is amazing.

Yael: It’s really great stuff.

Schwa: Yeah.

Yael: And he even writes to another individual, I’m assuming a friend of his, named Gitan Battista Spinoia. I probably am totally butchering that name. I apologize. “You did well to awaken me with your letters, Signore Giovanni Battista, for on the subject of corresponding with friends, I confess to slumber sometimes more than I should. I said, quote, unquote, “with friends.” From these, I exclude Signora Sarra, who is my mistress as you know.” And he goes on to say, “I should mention she has been as close to dying as she is from converting. I regret her obstinacy. Help her for pity’s sake with your prayers.” He goes on to talk about how distressed he is that his mistress, Padrona, is not getting closer to Christianity. So I think when you look at the letters as a whole, it’s clear to me that there are obviously romantic stirrings there. Or at least lustful stirrings. But it’s not clear to me whether or not those can be extricated from his desire to convert her.

Yael: So he does seem to be into her.

Schwab: Right. It’s not all an act just to convert her. He’s both interested in her and interested in her salvation.

Yael: So I know that this will come as a shock to many of you, but men in the 17th century sometimes were unclear about what they wanted. And also did not wanna define the relationship.

Schwab: (laughs)

Yael: I’d like to say that things have changed. #notallmen. But no, some of this rings true to me.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: And one of the most amazing tidbits that rang the truest to me, actually, because I feel like this is something that could happen with someone that you’re talking to on a dating app.

Schwab: Yeah.

Yael: Sarra Copia Sullam is her full name. The word coppia means couple in Italian. And early in her life, she spells Coppia, which is the spelling of the word couple, C-O-P-P-I-A. And he writes to her that like the two Ps in her name, they are united as a couple, in this word coppia.

Schwab: (laughs) Okay.

Yael: And she immediately starts spelling her name with one P.

Schwab: Definitely the best part of this entire story.

Yael: I love that story so much because I feel like that is a reaction that my friends and I could have to some creepy line on a dating app that’s supposed to be romantic, but comes off as super, super gross.

Schwab: Yeah. And then you have to change your name. Then you have to change your, like, contact info on the app.

Yael: It’s just hilarious to me because she obviously is interested in him as well. But, apparently, he took one step too far.

Schwab: She’s like, “Oh. Whoa, this has all gone way too far. He misunderstood why I sent him my portrait.”

Yael: Like, maybe he could’ve said, “We’re two peas in a pod.” But the two Ps in a couple was, was too much.

Schwab: So she changes her name.

Yael: Exactly.

Schwab: Wow.

Yael: So she becomes well known for her hosting of the salon and also for her correspondence with Ansaldo. And-

Schwab: Yeah, you said he publishes these.

Yael: I think he publishes them in 1623, which is five years after she first reads his book.

Schwab: Oh, so it’s not, not like every time he’s writing her, he’s also, you know, putting it out in the newspaper. This is the latest letter.

Yael: No.

Schwab: Okay.

Yael: I don’t believe so. We have 53 letters that he wrote to her. So if you take that and add the letters she wrote to him, we’re talking about, really, several dozen pieces of correspondence.

Schwab: Uh-huh.

Yael: And I think that because we also see that he wrote to his friends about her, it’s clear that this was not a secret. He also, apparently, wrote to her husband to bolst-

Schwab: That is a bold move.

Yael: It is a bold move. To encourage him to encourage her to become a Christian.

Schwab: (laughs) And I’m guessing that did not work.

Yael: It did not work. Again, we don’t know a ton about the emotional nature of her relationship with her husband. So, uh, you know, it could have been a loveless marriage, it could’ve been a marriage of convenience or it could have been a happy, romantic marriage.

Schwab: But even if it was a loveless marriage of convenience, I think most husbands probably not thrilled to be getting letters from Genoese monks about how their wives should convert.

Yael: So even, even in his most flowery and expressive letters about his love for her, he always ends them with his desire for her to convert. So the Christianity portion was definitely a big part of it.

Schwab: Yeah.

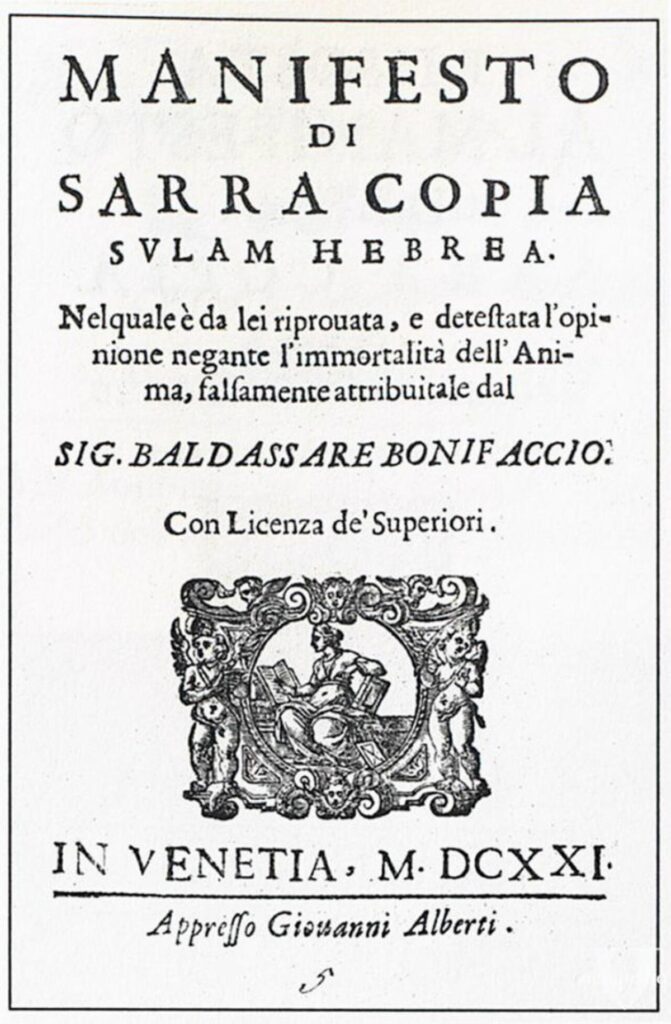

Yael: She, I think she is known in her circle a little bit as a dilettante or someone who is not quite as smart as she thinks she is. And at a certain point in time, she comes under attack by a gentleman named Baldassare Bonifaccio, who is a Christian, and I believe he is a member of her salon or a member of her community. And he is the one who accuses her of not believing in the immortality of the soul, and he makes this very public claim against her.

Schwab: I’m trying to understand the context because right now, I feel like if that charge was levied against someone in 21st century America, you know, “This person does not believe in the immortality of the soul,” it doesn’t seem like it would be the most important thing you could say about a person. But at the time, that was a very big deal, you were saying?

Yael: Yes, it was. It was something that would get you canceled in cancel culture. And I just wanna mention, her family was very, very close with Leon de Modena, who was the chief rabbi of Venice. They were not estranged from the mainstream Jewish community. We don’t know how, quote, unquote, “observant” they were by today’s modern standards, but they certainly were not outcast in the Jewish community. So to say that she does not believe in the immortality of the soul is strange and controversial.

And she immediately publishes a manifesto to challenge this notion that she doesn’t believe in immortality of the soul. It has an extremely-

Schwab: Does the, does the manifesto need to include much more than “I believe in the immortality of the soul”?

Yael: I think she does include some exegetical or analytical details.

Schwab: Oh, she’s gotta defend her position. She’s like, “I’ve always believed in the immortality of the soul. Here’s the justification for that belief. Here…”

Yael: (laughs) Exactly. One thing that she does that is really an instance of form meeting function is that she dedicates her manifesto to her deceased father. And saying, “You say I don’t believe in immortality of the soul. Joke’s on you. I’m dedicating this manifesto, in which I bolster my belief of immortality of the soul, to my dead father because I know that even though he’s dead, his soul is immortal and he can read this.”

Schwab: Huh. Seems like she’s able to put up a pretty strong defense of her belief of the immortality of the soul.

Yael: She is, but I’m not sure how well it goes over. I think that like many things in life, once the accusation was levied, that was the story that really took root and, and spread. She lost her relationship with Ansaldo thereafter, which maybe was not a bad thing. But she sent him a copy of the manifesto, and he did not respond to her for many, many months, which was unusual, for the speed of their general correspondence. And when he ultimately did respond, he was cold to her. And you could tell it was sort of the beginning of the end for them. She became a little bit of a joke in the intellectual circles in Venice. A satire was written about her, Le Satire Sarreidi.

Schwab: Because of this thing. Not because of her salacious correspondence with the monk, but because-

Yael: Correct.

Schwab: Which was all published.

Yael: The letters were published two years after the accusation.

Schwab: Ah. So it’s like whoa. Everybody knows this story, but he’s like, “Actually, do you know I’ve been writing letters back and forth to her for many years? Here’s all of them. And I’m not embarrassed about them!”

Yael: Right, But, that doesn’t mean that people didn’t know about the letters. I don’t know for a fact. But in terms of actual publication of a bound book or pamphlet, her manifesto was a pamphlet.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: The letters were published later on. And her life kind of goes downhill from there. Subsequent to this, the people who worked in her household stole from her… maybe she was disliked by them or disliked by others. She goes from being the socialite of the year in Venice, the person whose home everyone wants to be invited to and everyone wants to be around, to being just another disgraced wannabe woman author. There is a lot of cool information out there about her, I wanna talk about why we think this relationship developed, why she got so ensconced in this salon culture which really took off in Europe and was actually fairly centered around the Jewish community for several centuries. When you get to the 19th century in Germany, you really see Jewish women as the epicenter of these intellectual circles. I’m interested to hear your thoughts. But a lot of it to me, I think, stems from the fact that women at this time were literate. It’s likely that she was learned in Hebrew, Latin and Greek. But they were not permitted to study Torah. They were not permitted to study Jewish texts.

Schwab: That’s how they then wind up in the art scene.

Yael: Exactly.

Schwab: It’s so similar to, like, so many things that are, that are relevant in our modern world of like, “Well, if you get really involved in the art scene or in your campus culture, you know where that leads.” To questioning the belief of the immortality of the soul. You know? You get sucked into college campus and then it leads to the questioning of religion or the surrounding culture is going to infect with all of its ideas.

Yael: Right, and you’re gonna end up as prey for a Genoese monk. Who is, you know, gonna sleep with your picture under his pillow.

Schwab: Mm-hmm. And all he really wants is to convert you.

Yael: Exactly. You know, she is, to me, both an aspirational character in terms of her ability to bring together people who talked about a lot of important ideas and to educate herself and to have the outlet of writing and painting and poetry. She wrote some sonnets, I believe, as well. But at the same time, she is somewhat of a cautionary tale.

Schwab: But she doesn’t ever convert.

Yael: No, no, no. She, when she is accused by Bonifaccio of not believing in the immortality of the soul, she immediately takes it upon herself to refute that claim and to refute in a way that exemplifies her devotion to Judaism and its tenets, one of which is the immortality of the soul. So she does not ever go down the road of Christianity and she is not swayed by Ansaldo’s letters. We hear from him time and time again in his letters, “You are the most beautiful. You are the light of my life. You are this. You are that.” And then in the last two lines, it was like, “The only thing that concerns me is that, you know, fire and brimstone is going to befall because you have not accepted Christianity.”

Schwab: (laughs)

Yael: And she never goes there. You know, she was able to stand strong in that way.

Schwab: Which is sort of like the counterweight to that idea we were talking about before of, like, her falling prey to these things. Actually she has a lot of agency and her own ability to stand up for what she believes and what she wants. And, for all of the, the dangers of the world that she falls into, she, it sounds like, pretty steadfastly is, is true to herself and to her background.

Yael: Exactly. It’s a great advertisement for giving women the wherewithal to learn, and internalize what they learn so that they can put up a defense against these wayward influences out in the world.

Schwab: It’s so funny that the play that kicks off all of this is the story of Esther, which is so much that. Like, a young women who, you know, finds herself in the king’s court but does remain true to who she is and doesn’t, you know, change her identity and stands up for her people.

Yael: That’s a really amazing point that I had not considered. Esther could have very easily gotten to the palace and been like, “Eh, kinda nice here.”

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: “I’m treated pretty well. Why should I risk this existence by standing up for myself and the Jewish people?” And she doesn’t. She really takes matters into her own hands. I think that’s an amazing parallel, and I’m really glad you brought it to my attention.

Schwab: Huh, great.

Yael: So salacious, a little interesting, a little bit for the romantics among us. I don’t know if this story has a happy ending from a romantic perspective.

Schwab: It sounds like not really, right? You said, she sort of becomes a laughingstock and, and her household, people steal from her.

Yael): But does that mean it wasn’t worth it? Is it not better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all?

Schwab: Yes.

Yael: Nobody should take romantic advice from me.

Schwab: Yeah. Cool. Thank you so much for sharing this one. This is definitely an original character. I feel like we have not talked about a story that is like this in any way.

Yael: And I think obviously, our war heroes are important. Our government officials are important. And people who do crazy heroic things or crazy revolutionary things are important.

Schwab: Mm-hmm.

Yael: But she was just kind of a regular woman. I mean, obviously her defense of her religion and of her beliefs is certainly notable. But it is nice to talk about a different kind of person every once in a while.