Noam: Hey, everyone. Welcome to Wondering Jews with Mijal and Noam. And I’m Noam, and this podcast is our way of trying to understand the Jewish world. We don’t have it all figured out, and we’re going to try to figure some things out together. It’s what we do.

Mijal: I’m Mijal.

Mijal: Our absolute favorite part is hearing from you, so please email us at wonderingjews@jewishunpacked.com. And now, Noam, we have a question from our listener, Rachel. What is a kind act that someone did for you this last week?

Noam: Wow, that is, a lot of people are kind. Everyone’s kind. People are good people. People are good people! But the kindest act, I think for me, I was looking for a good sandwich

Mijal: What?

Noam: And, and I, and I asked my friends for their suggestion of the best tuna sandwich in town. And I got a great suggestion, which was, basically start making your own tuna. You go to the X bagel store, I won’t say. But to go to that bagel store, have it scooped out, onion bagel, put some honey mustard on the bottom, and then tuna, and then avocado. And I just thought that it was a really kind suggestion to me as someone who loves a good sandwich.

Mijal: Okay, Nam, I feel like we need to do more kind acts towards you, Nam, and not just suggestions of what sandwiches do.

Noam: I feel great. I’m looking forward to that now.

Mijal: Okay, that’s good. Well, I’ll just say I had an insane day today, was running back to back. And then when I stopped and had to do a lot of Zoom calls, I opened my bag and realized that I forgot my computer charger, which is really bad if you have to open up your computer and do stuff. But then somebody very kindly who I was supposed to meet with went out of her way and got me a computer charger. So that was a small act of kindness that made a really big difference in my day.

Noam: It is actually a really great thing. And I’d love our two examples, naturally your example is better than mine, but I will say that I think that when we think of huge acts of kindness or just being generous, we think of these tremendous moments, but I just love when people do little things like respond to text messages, emails, and those basic behaviors are just what leads to a kind culture.

Mijal: Yeah, agreed.

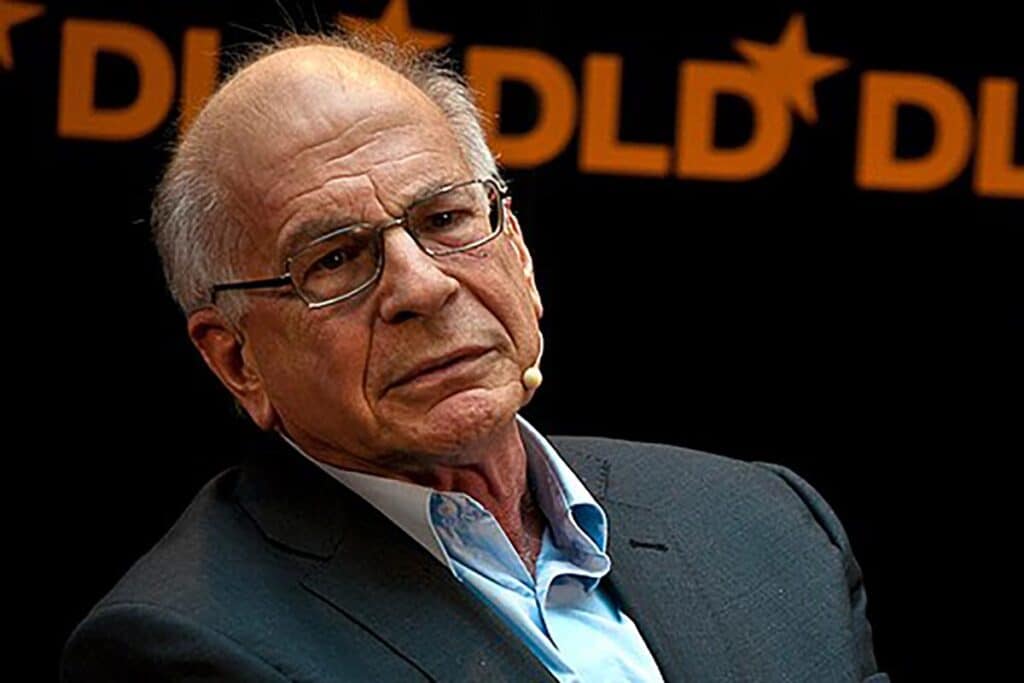

Noam: That’s what I think. Simple as that, simple as that. So here’s what I wanna do today, Michal. Today or last week was quite the heavy week in which we lost a few major giants in the Jewish world. One of them is Daniel Kahneman, Professor Daniel Kahneman, who is a Nobel Prize winner for doing things that I will not claim to understand. But he integrated psychological insights into economics and he fundamentally changed our understanding of decision-making. He wrote an amazing book called “Thinking Fast and Slow.”

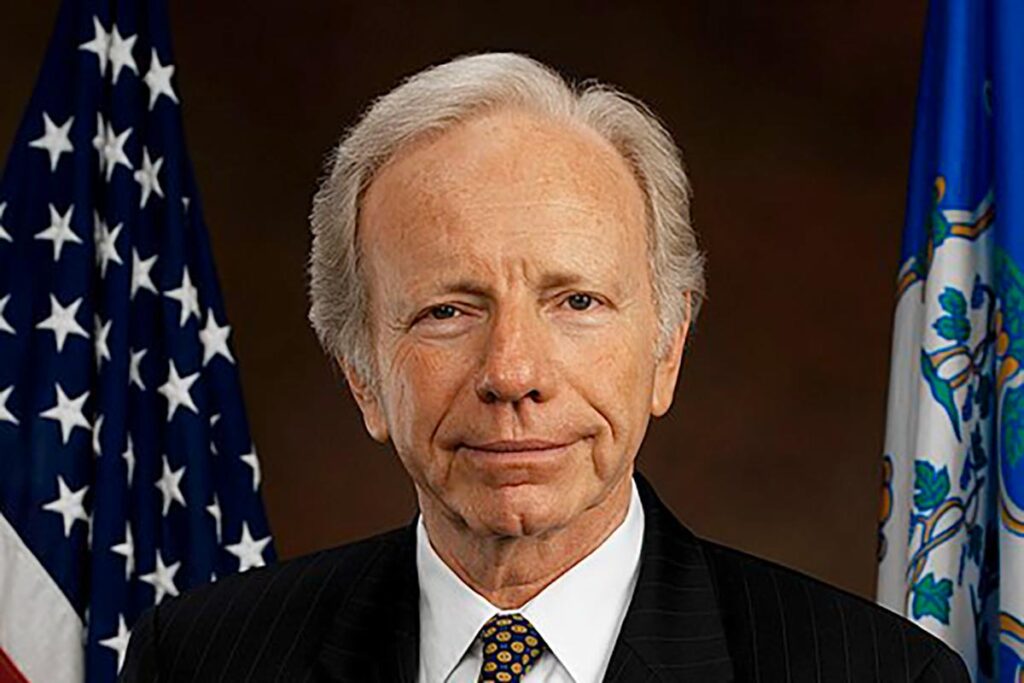

We also lost Senator Joe Lieberman, Senator Joe Lieberman, who was the first Jewish nominee for vice president and he was a major senator and a major leader. And on the same day, we lost both of them.

By the way, also, we also lost Professor Abraham Grossman, who was a major scholar in the world of biblical analysis and biblical study. A lot of people that we lost. And I want to just reflect on, maybe if we could reflect on Professor Kahneman and Senator Lieberman to talk about their lives and how that can influence the way we think about the world.

Mijal: Yeah, and I think that’s also just note, Noam, when we think about just the Jewish practices and Jewish culture, when people pass away, part of the way that we honor them is by trying to figure out what their lives meant and how we can learn from them in our own lives. So that feels like a good way to do it.

Noam: Yeah, so let’s start with Professor Kahneman. And again, this isn’t his bio. I’m not gonna do this sweeping eulogy of him, but I wanna talk about something that he said, or really that Cass Sunstein said about him, and get your reflections on that.

Cass Sunstein wrote in the New York Times recently, right after the death of Professor Kahneman, he explained that Professor Kahneman was able to work with a lot of people and specifically he was very interested in ensuring that people who strongly disagreed with each other knew how to speak to each other and that he believed that what happens is when you bring a difference of opinion together, you’re able to actually see disagreement that leads to something positive. Cass Sunstein explained the concept as adversarial collaboration, which meant that when people who disagree work together to test a hypothesis, they’re involved in a common endeavor. They are trying not to win, but to figure out what’s true. He says they might even become friends. How do you relate to that in terms of like today, in terms of the challenges of the day?

Mijal: Well, so I know that Professor Kahneman really wrote a lot and that he tended to work very closely with intellectual partners, sometimes for like years or like a really long time. I didn’t know that he would work with people who disagreed with him strongly. So can you tell me a bit more about that?

Noam: It’s even more than disagreed with him strongly, by the way. There’s a dynamic that he described as angry science, in which there were people who, once they proved whatever the hypothesis was, whatever their theory was, let’s say they would write a book on a topic or publish this grand article. Well, what happens when you publish a grand article on a topic? Your identity becomes tied up with the opinion you’ve been espousing all along. And the person that critiqued his work, Professor Kahneman reached out to, and actually said, I want to work together with you to figure out the truth. And that is, I think, remarkable to be able to do something like that.

Mijal: Right, that’s really cool. I’m just really curious, who was that professor, what was that example? I want to learn more.

Noam: Okay, I don’t remember the name of the professor, but what I remember is the argument was what leads to happiness. And can wealth lead to happiness? And Professor Kahneman made an argument on one side of the debate. This other scholar made an argument on the other side of the debate. And they both said, this is what we believe. Then they worked together. And then after working together, what they figured out was something that was actually quite fascinating. This is what was said.

They figured out that asking how a disagreement might actually be resolved tends to turn enemies focused on winning and losing into teammates focused on truth. And they found something that was much more complex as a result of what it is that they studied.

Mijal: Yeah, that’s awesome. I mean, some of what comes to mind, I think we spoke once about Abraham Lincoln and there’s all these like theories around Lincoln that he surrounded himself with like a team of rivals. And there’s actually a book about him called Team of Rivals. And it sounds very similar to what you’re describing to intentionally set up collaborative structures with people who really disagree with each other. I would also say it sounds really Talmudic. I mean, part of the methodology of Talmudic study and the way that Jewish law developed was literally coming up with like a Bet Midrash, like a house of study in which disagreement wasn’t just tolerated, but it was written down in the books as something we should study and that can lead to different kinds of conclusions.

Noam: Can I tell you what my absolute favorite teaching in the entire Torah is? And I just thought of it now after we started talking about this.

Mijal: You only discovered now that it wasn’t 4:14 from Esther. That’s your favorite verse in the book.

Noam: No, no, okay. All right. I understand. I have a lot of favorites. No, but it’s my favorite idea, one of my absolutely favorite ideas, that really helps me think about the exact same thing that Professor Kahneman spoke about, which is the story of the Binding of Isaac in which the Kotzker Rebbe, who lived in the late 18th, early 19th centuries, and just a very eccentric rabbi, a fascinating rabbi, someone who preached authenticity to the extreme. He explains this idea that I’m just like blown away by all the time, which is that the test of Abraham when he was sacrificing Isaac, and it’s a much bigger story, but his uniqueness was when he said, Now I know that you are a God-fearing person, said God to Abraham. That only takes place when Abraham, who had spent all of his moral and mental and spiritual energies going to slaughter his son. And then he only says, now I know you’re a God fearing person, when he chooses not to do that. And the idea is that when we commit ourselves to an ideology, when we commit ourselves to a worldview, what ends up happening is, we start to worship that identity. And so what I think is so awesome about what Professor Kahneman did is he says–

Mijal: Wait, wait, I still, I didn’t get your favorite idea.

Noam: Okay, the idea is when God says to Abraham, now I know you’re a God-fearing person, he only says that after he chose not to go forward with everything, with the idea being that he was gonna go forward with it, but I know that you’re God-fearing because you sacrificed yourself to this identity that you held onto to be willing to do this to your son Isaac, and then you pulled it back, and your ability to not tether yourself to the identity that you built up and to say, I have a unique and distinct identity and I’m not just going to worship that which I was about to do. Now I know you’re a God-fearing person. What Professor Kahneman is saying is the exact same idea as the Kotzker Rebbe, the exact same idea.

Mijal: I don’t know if he’s saying the same idea as the Kotzker Rebbe, but if what you’re saying is there’s something deeply Jewish and deeply powerful about having powerful and strong ideologies, but not having those ideologies kind of shape who we talk to or learn from, 100%. I’ll tell you, by the way, the other thing that I find really Jewish about his work.

So a lot of his work, and he’s Israeli by the way, which I didn’t know until after he passed away. I just thought he was like an American scholar. But, so much of his work around behavioral economics, it was really the marriage of psychology and economics. And I think one of his key ideas was that we are irrational beings and that we have all of these biases and loopholes.

Noam: Well, I’m rational. Everyone except for me.

Mijal: Everybody except for you, Noam. Yes, the whole humanity except for you. We are very irrational and we have biases and we have all the things. And part of what he was saying is like once you understand that, then you can actually create like systems to help you live better lives. So even like, once you understand that your brain gets triggered by seeing healthy food in front of you, you’re going to stop pretending that we’re all rational people who only eat what we’re supposed to and actually put more healthy food in front of people to help us eat healthier. And to me, I think that’s a very, very Jewish idea to like take deeply into account like human nature and to work with it, as opposed to pretend like it’s not there.

Noam: Yeah, I think that’s a great insight. Not just because my cabinets are filled with chips and sour sticks, and I try to stay away from them, but I look at them like, oh, that looks delicious. But what are ways that you think that in Judaism that is like, like what are other examples of that?

Mijal: Well, even like, we’re reading Leviticus in this week’s and it’s all about like sacrifices and offerings. And, and part of the way that I understand it is human beings have always had a need for like a physical conduit to the divine and the sacred. And so Jewish tradition and God and later the rabbis really came up with ways to work with human nature to help us come closer. You can think about the laws of kosher food as helping us like moderate our own eating habits. So I think that part of what I love about Jewish tradition is that I understand it as a tradition that takes into account human flaws and human biases and helps us become better.

Noam: Yep, works for me.

Mijal: By the way, Noam, I’ll give you just one more example.

Noam: Please.

Mijal: I was speaking with a, with a friend lately and helping her, like negotiate a work position. And I told her, listen, all the research tells us that women are just less good at negotiating. We are less confident in asking for certain money. We have certain biases that makes us more agreeable and less able to negotiate like a guy would. And I said to me, this is actually really empowering because once I know all of this, I’m going to work really, really hard to train myself in how to negotiate and to figure out what do I have to do to understand that I have been socialized, right, to be more agreeable. I’m so agreeable, right, Noam?

Noam: Ha ha.

Mijal: All the time. Whatever. Like, how am I going to make sure that I actually understand the way that I work, that I’m imperfect, that I have all these biases, and actually try to help myself with this in mind?

And to me, it’s like a feminist kind of like calling. Like instead of pretending that this, you know, that you and I are gonna negotiate in the same way, I’d rather kind of understand where I am and then train myself to get better.

Noam: Okay. Yeah. Yep. I feel like you’re a better negotiator than I am.

Mijal: I don’t know, no, we should try this out. We should try this.

Noam: By the way, I think it’s important to say for public consumption that I did on Saturday afternoon on Shabbat day, I give a lecture mostly, most often on Shabbat afternoons, and I publicly declared that Mijal Bitton, I changed my mind after she sent me a piece about the question that we explored in a previous episode about the Haredim and conscription. And I said, you know what? Mijal’s right. I am wrong and I publicly said that and I’m publicly saying that now. So thank you for helping me change my mind on an issue that I said I was persuadable but I did have a position on it. So there you go. You got it.

Mijal: Well, I love knowing that I was right, but what’s the connection between this and between our biases?

Noam: I’m just saying in terms of negotiating. Persuasion, negotiation, they’re all part of the same categories.

Mijal: Right, but a key lesson there, so I think we looked at two lessons that we learned from Professor Kahneman. Sorry, Kahneman, Kahneman. The H throws me off, I can write it, I can’t say it. I have that with English as third language. But one is that we should really work and collaborate with those who disagree with us.

Noam: Kahneman, Kahneman… yeah. Yeah. I know. I know, I know.

Noam: We really should. I love the concept of adversarial collaboration. I just think it’s so important. It’s so hard though. It’s so hard for people to do.

Mijal: Do you have a deep adversarial collaboration?

Noam: Yeah, with you. This doesn’t count?

Mijal: I don’t think so not, but I don’t know. Okay, give me other examples and then I’ll decide if this counts.

Noam: I think, well, I don’t know if I’ve, no, I haven’t launched any formal adversarial collaboration, but I was gonna ask you, and you beat me to the punch here, I was gonna ask you the question about whether or not there is an example of something that you have committed your life to, or you’ve committed some aspect of your identity to, only to be presented with other information, or another, you know, to use the Kahneman example, another study that was done.

And then instead of going back into a world of angry science where there’s a nasty world of critiques, replies, and rejoinders, and as a context where, as Kahneman said, where the aim is to embarrass, as Kahneman said. I wanna know, like, is there an example for you? Where you have seen an idea of yours that you said, like, that Kotzker Rebbi sort of approach of, you know what, I see this differently now, I’m going to be different about this issue. It’s very hard.

Mijal: Yeah, so I can speak, maybe I’ll give two examples. One is somebody who I think when we first met, we were adversaries, like politically and intellectually, particularly in terms of our views on Israel. This was like maybe 10 years ago. I think with this person, I think we had like an initial quick dislike of each other and being like, oh, we’re in different teams. And I think over the years, we actually learned to respect each other’s point of views and we’ve remained close interlocutors.

Noam: Hmm.

Mijal: We probably both changed our views, not because of each other, but in general, just, you know, maturing.

Noam: Do you both use the term interlocutor? See, I couldn’t say that word. I couldn’t say the word interlocutor. There you go. And it’s my first language. It’s my first language. And I couldn’t say it. Well, because you both use the term. By the way, there it is. We figured it out. If you have something in common, like using terms like interlocutor, then you could figure things out together. That’s a real win.

Mijal: We both use the term, we do, we do, that’s what bonds us. Interlocutor. Yeah, but he’s also, he’s somebody that I send articles to being like, hey, I know you’re gonna disagree with 95% of what I wrote, which is why I’m sending it to you. And I just want you to tell me, are there places where I’m obviously being not smart? Yes, yes, yes.

Noam: That’s great. Like your blind spot, their blind spot. Yeah.

Mijal: Yes, and I’m like, please give me the most, tell me what’s my weakest places so I can think about them, not because I’m gonna change my argument, but because I really respect you. So that’s one example, and then I have others. I definitely think, I’m actually usually afraid of the other thing, Noam, I’m afraid that I’ve changed my mind too much on some things across my life. Because I think, well, cool or not cool, you know?

Noam: Wow, that’s cool. That’s different. Yeah, I think it’s, I’m saying, I think it’s cool.

Mijal: Thank you, Noam, I’m not sure if it’s cool though.

Noam: Why?

Mijal: Because I think that, because I think there’s both dangers. There’s like the danger of being rigid and staying in your echo chamber and never changing. And then there’s a danger of being like so open-minded and so open to changing that you become less able to hold principal positions and sticking with them.

Noam: But here’s the thing, Mijal, I don’t, we’re close. Can I say we’re close? We’re close, we’re buddies.

Mijal: I thought we were adversaries.

Noam: Okay, we are close adversaries. I don’t think my guess is something that Mijal Bitton has to work on is becoming less principled. That’s, I think you’re good on that front.

Mijal: (27:55.966)

Okay, okay, no.

Noam: Well, so I want to transition, speaking of being with God, to a man that lived his life in an incredibly spiritual way, Senator Joe Lieberman.

Mijal: I was so sad. I was so sad. I had a really emotional reaction when I heard that it passed away.

Noam: Same, and why did you have such a strong reaction?

Mijal: I think, well, I didn’t know him, but I have like some, he was the stepfather of a rabbi that I looked up to, Rabbi Ethan Tucker.

Noam: Ethan Tucker? Yeah.

Mijal: and I’ve observed him throughout his public life. Number one, Senator Lieberman just came off as this incredible mensch. Like, just like, how do you translate mensch into English? Like good person in a world where politics have just turned nasty. And I think to me, he represented like certain values that I’m afraid our society is moving away from. So it felt like a real loss about somebody who embodied really, really amazing values and principles that we don’t have enough of.

Noam: Yeah, the words that come to my mind are principled, integrity, bridge building. And also I want to say another word, which is something that you and I have been speaking about, sacrificial. He was someone who was willing to sacrifice for his principles.

Mijal: What example comes to mind when you say that?

Noam: Well, the most obvious example that comes to mind is Shabbat, is his commitment to observing.

Mijal: Mm. Yes, He has a whole book on Shabbat.

Noam: He has a whole book on Shabbat, and I got to play you this clip. I know it’s silly, and Senator Lieberman, and it’s a serious topic, but did you ever hear this clip of John Stewart and Steve Carell talking about Senator Lieberman? Okay, I’m going to play it for you right now. I want to get your reaction.

[DAILY SHOW CLIP]

Mijal: No. That’s really awesome. I love that. But it makes me sad. I’m so sad.

Noam: Okay, yeah, yeah. Yeah, but it is sad, it is sad that we lost him.

Mijal: But it’s, it’s not just him. It’s what he represents. Somebody who wears his Judaism on his sleeve and his patriotism on his sleeve. I actually, you know, I taught in my class as part of his speech when he accepted the vice-presidentship nomination. Can I read you something from there, actually?

Noam: Yeah. Please, please, yeah.

Mijal: It’s a magnificent speech, we can put it in the show notes, but he speaks about a certain version of the American dream that is now not popular. He starts off saying, is America a great country or what? And he says, in my life I have seen the goodness of this country through many sets of eyes. I have seen it through the eyes of my grandmother. She was raised in Central Europe, in a village where she was often harassed because of the way she worshiped God.Then she immigrated to America. On Saturdays, she used to walk to synagogue, and often her Christian neighbors would pass her and say, Good Sabbath, Mrs. Manger. It was a source of endless delight and gratitude for her that here in this country, she was accepted for who she was. Later on, he speaks about his own work. He was active in the civil rights movement.

He says, I have tried to see America through the eyes of people I have been privileged to know. In the early 1960s, when I was a college student, I walked with Martin Luther King in the March on Washington. Later that fall, I went on to Mississippi when we worked to register African-Americans to vote. The people I met never forgot that in America, every time a barrier is broken, the doors of opportunity open wider for everybody. And it continues, and It’s to me, like when I moved to America when I was 12 and I was young but I already loved America and I had this idea of what it was and everything Senator Lieberman stood for, his ability to work across the aisle, his pride in being a Jew and being an American, his decency, his care for like the environment and people’s like rights to have access to healthcare, like all of these things, this decency, this patriotism, I was laughing when I heard that and I’m also just so, I’m really sad.

Noam: I’m really sad also, and I’m sad for every single reason that you said. And also because of the idea that his stepson, Rabbi Ethan Tucker said in his eulogy, which was that he described Senator Lieberman as a man whose insides reflected his outsides and vice versa. And meaning that he was a person of integrity.

He was a person of principle. He was someone who was genuinely kind. I didn’t know him. I’m not gonna claim to know Senator Lieberman in the sense that I’m spending time with him, but I was with him on a Passover program probably 10 years ago in Princeton, New Jersey. And, he didn’t act like he was Senator Lieberman.

And so for eight days, you could see someone, you could watch someone, you could see how they hold themselves in line when they’re getting food. He didn’t act differently. And I was blown away by his integrity, by his seriousness, but also his just like down to earthness, just in line with anyone else. You’re gonna grab another slice of pastrami, you’re gonna have some chicken, you’re gonna go vegetarian, where you going with? That’s who Senator Lieberman was to me.

Mijal: And you know what I wonder now? I was really thinking about this because I often look at this, I felt this way also when John McCain passed away, like a deep sense of loss beyond, and they were friends. They were such good friends, yeah.

Noam: Yeah. And they were politically not exactly the same.

Mijal: Not the same at all. And I felt a deep, deep sense of loss. And I wonder, I think there’s like this human proclivity, this human nature thing, to always look at the past and be like, oh, the good old days, the good old days when we had decency and loyalty. Back then we had good values and kids weren’t all like entitled and.

noam weissman: right? kach- kachayinu! kachayinu, this is the way it was, it was amazing

Noam: You know what? Ed Koch, the former mayor of New York said, it never was the way it was.

Mijal: But, but, right, I know, so, but, but here maybe it was a little bit, and you know, there.

Noam: Maybe it was the way it was yeah.

Mijal: Yeah, and I think there is this Jewish idea of like looking at our elders and those who came before us, and actually learning from them. Like I think part of what, for me, part of what it means to be a traditional Jew is that I am, the past is not just something I want to escape, but I want to revere and learn from, you know. We have what to learn, yeah.

Noam: Yeah, yeah, 100%. I love that, I love that, I love that. I want.

Mijal: You know, we say in our community, you know, we say, I don’t know how to say it in English. It’s like, there’s like a certain grief and loss for those we have lost. And we have the grief, right? We are bereft.

Noam: Yes, exactly. Speaking of being bereft, there was something else that he said that I struggle with that I don’t know what to do with. He was on one of our good friends’ podcasts, David Bashevkin’s podcast, 18Forty.

Mijal: Senator Lieberman?

Noam: And I’ll play the audio for you, he said the following. He tells a story where his family, where he was just told he had the opportunity to become the vice president for Al Gore. And Vice President Gore said to me, Lieberman, I decided a couple weeks ago that you were my choice, but I really felt it would be irresponsible if I didn’t ask some people I trusted privately, did they think America was ready for a Jewish vice president, or would it make it impossible for our ticket to win? And this is like where I start getting a little bit like sad. He said it was fascinating because I asked some of my Jewish friends and counselors and among them there was anxiety and uncertainty and some actually said don’t do it how America’s not ready. He said by contrast every Christian friend counselor asked about it said, oh don’t even worry about it. It’s not going to be a problem at all. Then he told a little joke which was since I know that there were so many millions more Christians than Jews in America I can make the choice that I wanted to make.

Mijal: Wow, wow, wow. Noam, what do you make of that? What do you make of the fact that like, even then, Jews have so much anxiety?

Noam: So is it… well, I think… It’s not just Jewish anxiety to me. It’s a lack of Jewish self-confidence and, dare I say, Jewish pride that is comfortable with someone to wear a kippah, a yarmulke on their head to be able to be externally and proudly Jewish and to realize that Judaism can bring to the United States of America an ability to fulfill its finest and most ethical ideals and to not be ashamed of that. I don’t know if Senator Lieberman is right or not right or if the story with potentially president Al Gore, you know, whether or not it’s right or, I don’t know, but the story rings true to me. And I think Jewish people feel uncomfortable at times with public displays of one’s Jewishness. And friends, game on. Let’s go.

Mijal: Yeah, the only thing I would say now I’m with that, I think a year ago I would have agreed with how you put it, lack of Jewish pride, today. I literally read an article in Jewish Review of Books a couple of months ago, but I forgot the author’s name. But what I think he said is that one of the only ways to prevent antisemitism is to actually not have prominent Jews in offices around the world, because when you’re a prominent, whatever, I do think that there is, I just want to say there’s like a line between like not having pride.

Noam: This just makes me laugh.

Mijal: Yeah, and having anxiety. I would say this is part of why, but part of why I’m sad, Noam, is that I do think some things have changed in America. Like, I do think, I don’t know how things would be right now if Joe Lieberman, you know, started his career because of how, you know, the cover in the Atlantic a few weeks ago about almost like the end of a golden era for American Jews? Franklin Farr wrote, the golden age of American Jews is ending. And it’s a really, it’s a worthwhile article to read and grapple with. I’ve been thinking a lot about it, but I do sense something there that I agree with that a certain golden era and age is ending and Senator Lieberman’s stature, I think, symbolized when he was at its height. Like this ability to confidently hold America and Jewishness together and America accepting that and Jews accepting that and feeling comfortable expressing a certain patriotism, that it’s just so much less normative right now. And I am sad not only because of his passing, but also like he symbolizes a certain end of an era, I think.

Noam: Yeah, well, it’s our job to pick up the pieces that Senator Lieberman and Professor Kahneman left for us and to…

Mijal: And they both believed in friendships across the aisle. You know what I mean? It’s, yeah.

Noam: Exactly. Yes. Friendship across the aisles, being willing to engage with people with whom you disagree, being able to be principled. That doesn’t mean not being principled. Taking a stand and what you believe is also strongly okay. Highly recommend it. And to have what the term of adversarial collaboration without just totally marrying your, and your ideas with your selfhood and to be able to separate the two without and I like what you said, I really like what you said, Mijal. I really like what you said about the challenge of, just because we believe in the ability to change our mind doesn’t mean we should be so open to the to the point that we are not anchored in our ideas. I think that is so incredibly important. So I love that point.

Mijal: Yeah, at different times when you talk about pluralism and its dangers and possibilities. But you know, Noam, the expression that we say when someone passes away, one of the expressions that we use after their names is zichronam l’v’racha, which means may their memory be a blessing. And we can think about that almost like in a theological way, spiritual way, but to me it’s almost like a rejoinder to us here on earth, to ask ourselves how do we take their memories and use those inspirations for us to bring more blessing into the world, inspired by them.

Noam: Yeah. So may Professor Kahneman’s memory be for a blessing, may Senator Lieberman’s memory be for a blessing.

Mijal: Okay. All right. Great to see you.

Noam: All right, see you next week.