For such an exceptional guy, Moe Berg had a pretty unremarkable childhood. He was born in the early 1900s to immigrant parents and lied about his last name to avoid antisemitic bullying from the neighborhood kids.

By the age of 3, Berg was begging his mom to let him go to school, where he excelled at sports, academics and languages. On top of that, he had a photographic memory.

It’s no surprise he ended up at Princeton, where his skills attracted the attention of Major League Baseball scouts. For all his success on the diamond, Berg often felt like an outsider. After all, he was in one of the fanciest, waspiest institutions of 1920s America. Being a Jew wasn’t exactly an asset.

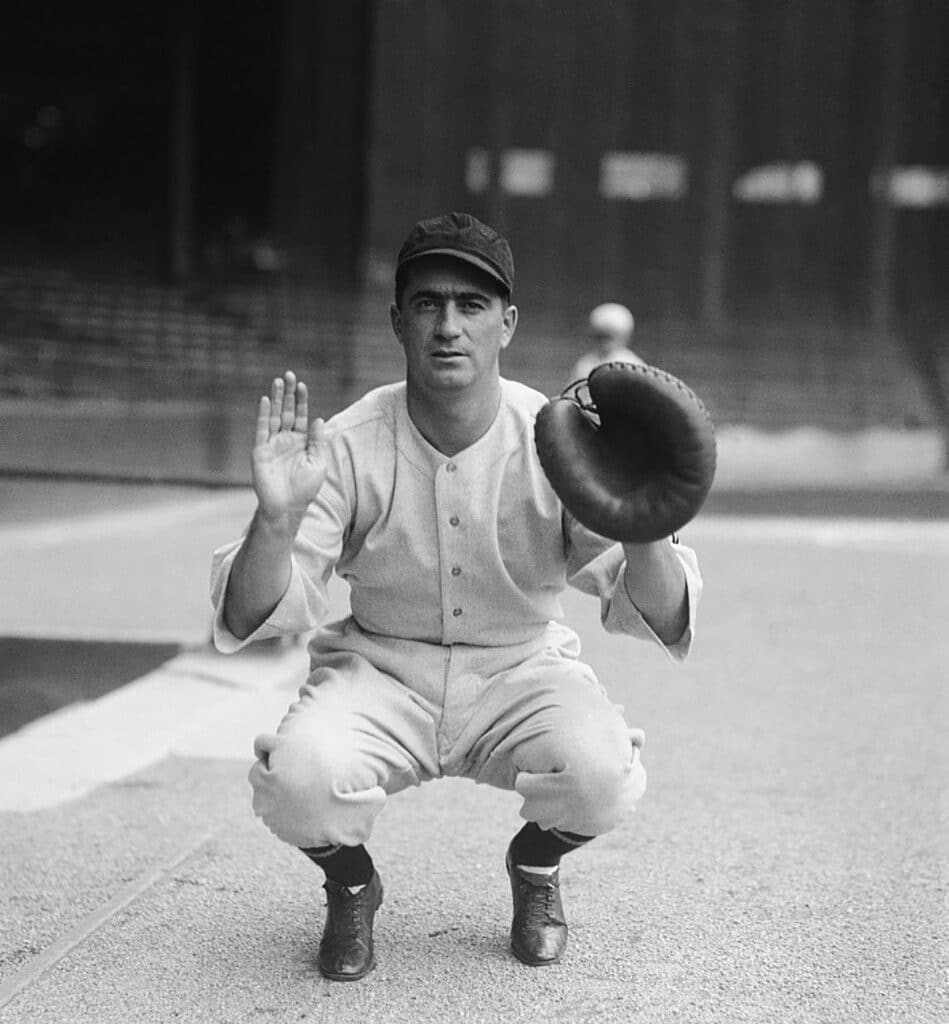

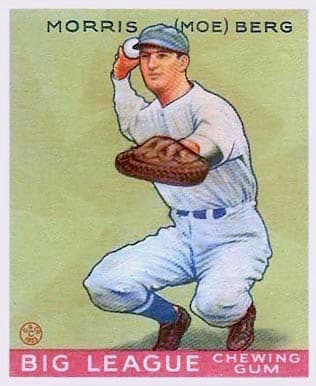

Things started looking up for Berg when he landed a spot on the Brooklyn Robins. When he wasn’t on the field, he was in the classroom, eventually earning a law degree from Columbia in between baseball seasons.

Berg wasn’t the best baseball player around. Although he played for a series of big-name teams, including the Red Sox and the White Sox, as far as major-league athletes go, he wasn’t anything special. However, that didn’t stop him from touring Japan with the biggest names in baseball, like Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. It was this 1934 tour that would change the course of his life.

Berg brought a portable film camera with him to Japan, which he used to film everything he saw. There are different accounts as to why he showed up with a camera. Some believe that he’d been recruited by the government, which was keeping an eye on Japan.

Others say that he’d offered his services to a newsreel production company. Whatever the reason, Berg filmed all of downtown Tokyo. For nearly a decade, the footage sat somewhere in his house, an exotic souvenir from his stint in East Asia.

After his world tour, Berg took a step back from playing and started coaching rookies. He wrote an essay that the New York Times called “one of the most insightful works ever penned” about baseball. He went on radio quiz shows, fluidly answering question after question like a 1930s Ken Jennings.

When Japan attacked the U.S. in December 1941, Berg broke the mold for aging athletes. He started working for the government, eventually landing a position with the U.S. Office of Strategic Services, which would eventually become the CIA.

What did an American intelligence agency want from a semi-retired athlete?

For one, Berg had a fluent command of multiple languages. Plus, he was a coach and an athlete, so he was a pretty good candidate to train his fellow Americans for secret parachute drops into enemy territory.

He was also a good candidate to oversee the kidnapping of Italian rocket scientists. He managed to coax a high-level Italian aeronautic engineer to the U.S. Moe Berg had landed a big fish, and President Franklin Roosevelt commented, “I see Berg is still catching pretty well.”

Berg’s most exciting mission didn’t rely on his athletic skills. It relied on his famous brain. The American government was understandably very concerned about the Nazis’ nuclear project.

The OSS, the predecessor to the CIA, sent Berg to Switzerland to hang out with Werner Heisenberg, a key scientist behind the Nazis’ nuclear program. In between his nuclear research, he lectured abroad.

He came to Heisenberg’s lecture with three things: a self-taught overview of nuclear physics, a pistol, and a clear directive from his bosses at the OSS. If Heisenberg indicated at any point that Germany was close to developing a bomb, Berg was told to shoot him on the spot.

Lucky for Heisenberg, the Germans weren’t close to developing a nuke, but the only way to know that was to send in a man who understood science jargon and could ask intelligent questions in a variety of languages.

Berg returned to the United States, and in time, the United States returned to the status quo. The OSS disbanded. The government started handing out medals to all the heroes of the war effort — including Berg. He refused to accept the Medal of Freedom, saying it “embarrassed” him. Berg’s brother said later that he was different after the war: moody, irritable, listless. No one is really certain why.

It may have been due to the CIA refusing Berg’s request to send him to the newly-created State of Israel in the early 1950s, or because his very last mission for the organization ended in failure. He had made some valuable contacts during WWII, and the CIA was very interested in what those contacts knew about the Soviets’ nuclear project, but Berg came back from Europe with nothing.

After that mission flopped, Berg never really worked again. He disappeared from public life and moved in with his siblings. He wasn’t a total shut-in. He traveled and saw close friends. But as he got older, he spent much of his time absorbed in his books.

However, Berg was a baseball lover through and through. According to his nurse, his last words were, “How did the Mets do today?” After his death, his sister accepted his long-deferred Medal of Freedom and donated it to the Baseball Hall of Fame where he is now recognized as a proud American Jew.