Remember middle school field trips?

Too many kids piled onto a bus, just absolutely out of their minds with giddiness about not being in school. There’s just something about all those kids gathered in one place, doing something new, that gives them all that loosed-from-the-cannon energy. Didn’t matter where you were going, either. A nature preserve, an Orioles game, a museum. I remember very few details about these childhood field trips.

But I do remember one extra-special field trip: getting up ridiculously early to travel from Baltimore to New York City to participate in the Israel Day Parade. (Which is exactly what it sounds like, by the way: Jewish kids in matching t-shirts marching down the streets of New York waving Israeli flags and singing songs.)

It was on our way to my very first Israel Day Parade that I first heard the names that would become a major part of my life. Because at some point, in between the chaos, the adults shut us all up long enough to tell us about four strangers a million miles away. Their names were Zachariah, Yehuda, Zvi, and Ron. Names that any of us could have had. I knew several Zachs, a Yehuda or two, at least one Zvi, and I have an uncle named Ron.

But these boys weren’t my age, and they weren’t on their way to a parade. They were IDF soldiers, who had been missing for about as long as I’d been alive. And yet, there they were, invisible ghosts on a bus full of young American Jews. Reminding us of the heavy price of defending Israel.

I don’t remember much of the parade that day. But I remember the stories of those captured soldiers. Zachariah was an American, just like us. He’d moved to Israel at the age of 10 — just like half of my super Zionist middle school. Gone to a yeshiva, just like I would one day. Joined the IDF, like a handful of my friends from my senior class in high school.

But unlike anyone else I knew, Zechariah had manned a tank during one of the worst battles of the 1982 Lebanon war. A battle in which 21 IDF soldiers died, another five taken prisoner. Two of the missing soldiers were later returned to Israel alive. But Zechariah — and his fellow soldiers Yehuda and Zvi — were not so lucky. By the time I heard their names in 1996, they’d been MIA for 14 years. Vanished without a trace.

And then there was Ron, shot down over Lebanon in 1986 and presumed to be held by the Lebanese. No, the Syrians. No, the Iranians. No, he had died in captivity. No, he was alive. A decade after his capture, and still, no one knew a thing. And in 1997, we added another name to the list: Guy Hever, a 20-year-old soldier who went missing in the Golan Heights and hasn’t been seen since.

By the time I reached high school, these names were like a litany. A camp I went to in Israel that summer even gave us all dog tags etched with all five names. Literally and figuratively, Zechariah and Yehuda and Zvi and Ron and Guy stayed close to our hearts. We prayed for them in school every Monday and Thursday when we read for the Torah. We would say a special prayer, or mi she’berach, for these soldiers who were MIA. I don’t recall anyone thinking or believing they’d be returned to Israel alive. But that’s not why we prayed. We prayed because they deserved our prayers. Because their families deserved healing, the tiniest scrap of closure. Because of what it means for us in Baltimore, Maryland, to make sure we were connected to our Jewish brothers in Israel. And because, who knows about the strength of prayer? Who knows?

But, when I pause, I reflect and say, it’s a little insane, right? Can you name all the MIAs from your country’s army? Because I’ll tell you right now: I’m an American. My country’s been at war for most of my adult life. But if there are any American MIAs in Afghanistan or Iraq, I don’t think I can name a single one. Even high-profile cases of people who are basically kidnapped by other countries — the Brittany Griners or Otto Warmbiers — don’t command the same kind of power. Sure, we kinda know who they are. We may have heard about them and said that’s terrible. But I haven’t seen bumper stickers with their faces, or protests and rallies in their honor for years and years. I haven’t seen mass demonstrations outside the UN or protest tents at the White House.

But those bumper stickers and protests and rallies and marches and tents and social media campaigns: that’s what Israelis do when one of their own is kidnapped. And it’s important for us to understand why. Why do captured Israeli soldiers haunt the Israeli psyche? Why are kids five thousand miles away wearing dog tags with their names? What makes Zechariah and Yehuda and Zvi and Ron and Guy different from Brittany Griner or Otto Warmbier? And as we go through this episode, I also want you to think about this question: is this collective fixation a good thing for Israel? Should the public’s sentimentality drive Israeli policy decisions?

But there’s another value at work here, too. And that’s the Jewish concept of pidyon shvuim, the ransoming of captives. Yes, Jewish law has a lot to say about kidnapping, it turns out. (I guess kidnapping was pretty common back in the day.) Jewish scholars were unequivocal about the community’s responsibility toward a captive Jew. According to Maimonides, AKA the Rambam, the 12th-century rabbi, doctor, philosopher, and absolute giant of Jewish law, quote “There is no religious duty more meritorious than the ransoming of captives.” The Shulchan Aruch, the 16th-century codex of Jewish law, agrees: “Every moment that one delays unnecessarily the ransoming of a captive, it is as if he were to shed blood.” Clearly, pretty serious stuff.

Pidyon Shvuyim is considered a mitzvah rabbah, a great mitzvah. And as former Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett said in 2022, “Redeeming prisoners is a Jewish value that has become one of the holiest values of the State of Israel… It defines us and makes us unique. We will continue to act to bring our sons home from anywhere.”

Israel is a secular state. But the religious injunction to redeem captives is hard-coded into the Jewish DNA. Why? I’m guessing here, but I’d chalk it up to two reasons: one is the principle of areyvut, of belonging, of Jewish people making sure they are literal guarantors for the other. And also to a couple thousand years feeling pretty vulnerable, subject to the changing whims of local leaders. For millennia, Jewish lives were disposable. Cheap. We had no power. We had no one to rely on but ourselves.

But that’s not the case anymore. The concept of Pidyon shvuim now has the backing of an entire government, an entire military, an entire intelligence apparatus. And so, the question has never been should the State of Israel ransom a kidnapped soldier? It becomes instead what price are we willing to pay? And make no mistake: the price is growing increasingly steep. Israel’s enemies know exactly how to exploit this weak spot in the Israeli – and Jewish – psyche. And that loops the question back around on itself: does Israel’s policy of bringing its captives home actually incentivize future kidnappings?

Because the terrorist groups who kidnap teenagers operate under a sick calculus. MIAs are Israel’s weak link — the country’s most vulnerable soft spot. Imagine the least imaginative kidnapper in a bad hostage thriller. Who is he kidnapping to extort the hero? The kid? The wife? The brother? Terrorist groups use the exact same logic on Israel. You want to hit the country where it hurts? Kidnap their kids. Take a teenager, a young person, sacrificing years of his or her life to defend their state. Hold him for years. And squeeze every ounce of leverage you can from your shiny young bargaining chip. An IDF soldier is everyone’s daughter. Everyone’s son. Everyone’s brother, sister, cousin, grandchild, neighbor. And I don’t know about you, but if it were my brother or sister or kid, I’d do anything to get them back.

But I’m a private citizen. I’m not the leader of a country, responsible for millions of sons and daughters and brothers and sisters. And that’s where it starts to get complicated. I’m going to tell you four brief stories, stories that give you a glimpse into the important stories of captured soldiers in Israel. Each illustrates a different facet of this no-win equation. And each explains a little piece of why Israel makes the difficult decisions that it does to bring back its kids.

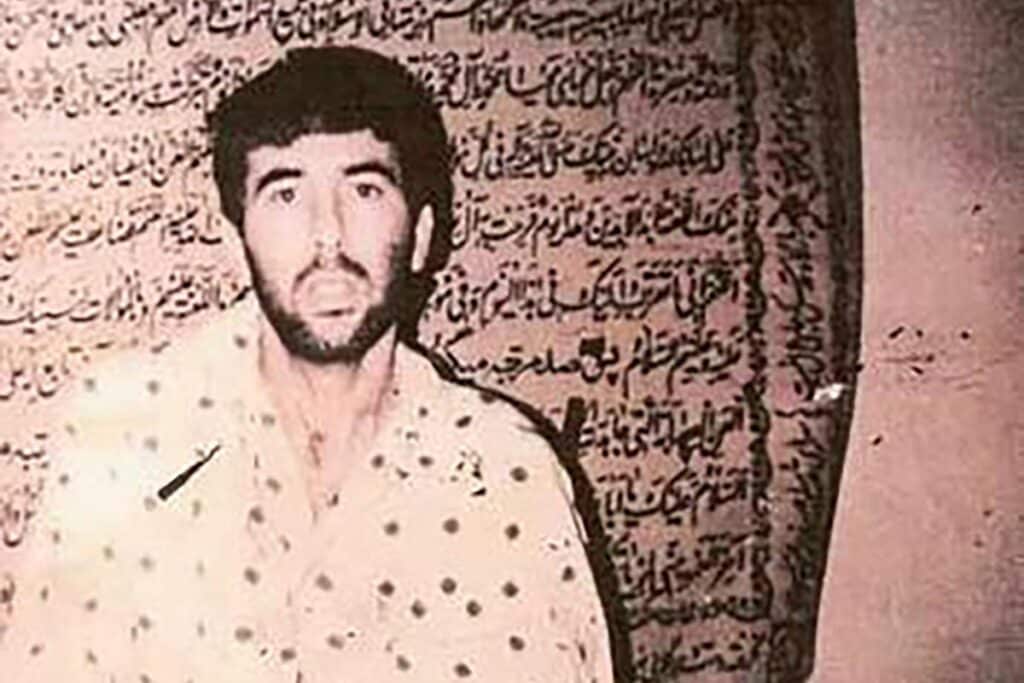

Number 1: Ron Arad, 1986

Ron Arad was 27 years old in 1986. He had a beautiful wife, a 15-month-old daughter, an unfinished house he was hoping to move into soon, and a promising career as a chemical engineer with a degree from one of Israel’s top universities. Arad had served in one of the most prestigious units of the Israeli army — the Air Force. But like most Israeli veterans under 40, he never quite finished his army service. Every year, he was called back for reserve duty. So when he was called back in October of 1986, he went.

The mission was routine: bomb a PLO target in southern Lebanon. Easy peasy. But something went wrong. One of the bombs rebounded on the jet, and though the pilot of his jet was able to parachute to safety, Arad was not. Wounded, he fell into the hands of the Amal militia — which, nerd corner alert, spent decades fighting the Palestinians. They also had beef with Hezbollah. But this was no enemy-of-my-enemy-is-my-friend situation. The Amal militia were not good guys.

Arad was an Air Force navigator. A husband, a father, and at 27, still so heartbreakingly young. The Israeli government was desperate to get him back. According to Israeli journalist Ronen Bergman, in his book Rise and Kill First — which I feel like I talk about all the time, and seriously, all of you should read it, it’s awesome — Israel launched, quote, “the biggest search operation ever conducted in modern history for a single person. There was no stone that we left unturned, no source that we didn’t enlist, no bribe that we didn’t pay, and no scrap of information that we didn’t scrutinize.”

But Operation Body Heat — yes, that’s what it was called, and I’m sorry, but that name is gross — turned up nothing. Israel even kidnapped the former head of the Amal militia, as well as a member of Hezbollah, to try and find out what happened to Arad. Under interrogation, the prisoners suggested that Arad had likely been held in Tehran for at least a little while. But no one seemed to know where he was now. Though Israeli intelligence concluded in 2016 that Arad probably died sometime in 1988, the search for him continues. Indeed, in 2021, then-Prime Minister Naftali Bennett alluded to a recent operation to locate Arad’s remains — an operation that has, once again, turned up nothing concrete.

And now, it’s 2023. Arad’s daughter Yuval is 38 years old — more than a decade older than her father was when he went missing, a mother herself. The house her father began building when he disappeared in 1994? It stands empty, waiting for Ron to return home. It’s a tragic story, to be sure. And I don’t want to minimize the Arad family’s pain. But you’d be forgiven for wondering, doesn’t Israel have better things to do with its resources than track down a ghost? And that’s a fair question. One that a number of Israelis have asked. Even Arad’s wife Tami has begged the intelligence community not to risk the lives of soldiers just to get her husband’s remains. In her words, quote, “We also asked that if it is discovered that Ron is not alive that they don’t pay a price to bring [his body] back. Not because it is not important to us to bring him home but because we believe this message will save the lives of captives in the future. We have requested and continue to request that they continue to search for Ron as long as possible, with the condition of no risk to life.”

And so the search continues, presumably. And why? Well, IDF Reserve Brig. General Ephraim Segoli has some thoughts as to why Arad sticks in Israel’s collective imagination.

“Okay, first of all it’s the halo of an airman that disappeared and the promise that we have to bring our fighters, no matter where they come from, back home and it was not done. This aircrew that was sent to this mission was not brought back home and it opened a trauma or a wound in our society which was much beyond the Air Force.”

Listen to that language. A promise. A trauma. A wound. It’s as though the IDF has a contract with its soldiers. You defend this country, and we will protect you. We won’t leave you behind. And when that promise is broken, what is left? The fear that you, or your son, your brother, your husband, could be next. And in a tiny country that drafts the majority of its citizens, that fear is neither irrational nor theoretical. It animates every operation. Every raid, every skirmish, every intelligence-gathering mission. How can a country ask children — teenagers, some of them! — to risk their lives without a guarantee that the state will do everything it can to bring them home, dead or alive? Ron Arad has long since ceased to be just a man to anyone but his family. For the rest of us, he’s a symbol of a promise, not yet fulfilled. One that the Israeli government is still trying to rectify.

So that was the story of Ron Arad. Neither the first nor the last of Israel’s captured soldiers. Less than a decade later, Israel would experience another collective trauma. But this time, the tragedy had a resolution.

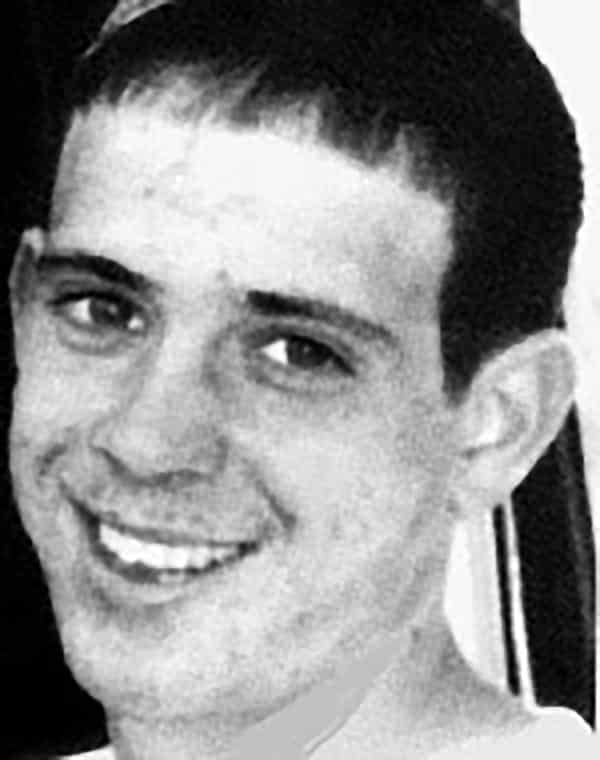

Number 2: Nachshon Wachsman, 1994

Remember our episode on Oslo? Link is in the show notes, but here’s the gist: as the Israeli government and the Palestinian Authority took tentative steps towards recognizing each other’s right to exist, terrorist groups like Hamas and Islamic Jihad stepped up their reign of terror, murdering 37 Israelis in 1994 alone.

Among the most traumatic of these operations was the abduction of 19-year-old soldier Nachshon Wachsman. Wachsman was the third of seven sons in a deeply religious family in Jerusalem. His mother was born in a Displaced Persons camp to two Holocaust survivors and moved to Israel in the 60s, certain that the Jewish state was the only place for a Jew to be. She was proud of her sons, serving in the IDF! Like his older brothers, Nachshon was determined to serve in an elite unit, and he ended up in a prestigious commando unit called Orev Golani.

It was in his capacity as an Orev Golani soldier that Nachshon was called to attend a training course up north. He left on October 9th, 1994.

Two days after Nachshon was supposed to have returned, his family got the worst call I can possibly imagine. Israeli Television had gotten a video tape from a Reuters photographer. Could they come to the Wachsmans’ house and show it to them privately before they broadcast it to the public? Stunned and horrified, the Wachsmans watched the tape, which showed their son tied up and held at gunpoint by a man with a keffiyeh wrapped around his face. The man held up Nachshon’s ID and rattled off his information: address, ID number. And then, with a gun pointed at his head, Nachshon spoke too. I’m being held by Hamas, he said. Please free Sheikh Ahmed Yassin and 200 other Hamas prisoners or else I’ll be executed on Friday at 8pm. (For a refresher on Ahmed Yassin, check out our Hamas episode, linked for you in the show notes.)

Israel had four days to figure out what to do.

Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin told the world in no uncertain terms that he would not negotiate with terrorists. The Wachsmans, who were American citizens, reached out to anyone they could — including representatives of American President Bill Clinton. Even Yasser Arafat got involved, calling up the Wachsmans and personally assuring them he’d “leave no stone unturned” to find their son.

I remember being 9 years old, watching this story unfold. We were watching, but it kind of felt like praying, in front of the 25-inch box TV in my parents’ bedroom. The days passed, agonizingly slow. 24 hours before Nachshon’s planned execution, one hundred thousand Jews showed up at the Kotel to pray. Nachshon’s mother later described the scene: “Chassidim in black frock coats and long side curls swayed and prayed and cried, side by side with young boys in torn jeans and ponytails and earrings. There was total unity and solidarity of purpose among us — religious and secular, left-wing and right-wing, Sephardi and Ashkenazi, old and young, rich and poor — an occurrence unprecedented in our sadly fragmented society.” That same night, Rabin and Arafat won the Nobel Peace Prize for their work on the Oslo Accords — an odd and bitter irony considering the ticking clock.

Unbeknownst to anyone, the elite Sayeret Matkal unit was gearing up to rescue Nachshon, who was being held in an Arab village inside Israel, barely ten minutes from the Wachsmans’ home. But the operation was a failure. Nachshon was being held behind a solid steel door that the unit failed to breach. With the element of surprise lost, the unit heard the gunmen shooting Nachshon dead. Though Sayeret Matkal managed to kill three of the Hamas men, they lost another one of their own in the firefight: the team’s commander, Captain Nir Poraz.

It was a national tragedy. Thousands attended Nachshon and Nir’s funerals. And every day of the shiva, the traditional week-long mourning period for the family, Israeli radio began its broadcasts with the words “Good morning Israel, we are all with the Wachsman family.” Meanwhile, Prime Minister Rabin defiantly addressed the press in a news conference: “This is part of a policy of fighting terror til its bitter end.”

For the six days of his captivity, Nachshon was everyone’s son. Everyone’s brother. His family appealed to the country, begging them to pray, to light Shabbat candles, to get just a little closer to Judaism in honor of their son. And the country complied. In the span of four days, Jews across Israel sent the Wachsman family over thirty thousand letters describing the mitzvot they were taking on in Nachshon’s honor.

It was beautiful. And it was heartbreaking.

Like the case of the Ma’alot massacre — yes, link is in the show notes — the Nachshon Wachsman story shook Israel’s confidence. This was the country that had once rescued Jewish hostages from Uganda (link in the show notes). The country that had sneaked into Lebanon — dressed in drag, no less — to blow up PLO installations and come home without a scratch (again, link in the show notes). But in trying to rescue a soldier — someone’s son! Everyone’s son! — the government had accidentally sentenced another of Israel’s sons to die.

Was this the price of a rescue mission? Was this the price of a soldier’s life?

Nachshon never made it onto the dog tags with Zechariah-Yehuda-Zvi-Ron-Guy. In his case, there was no uncertainty. He had been missing for six days, and now he was gone. But you’d be hard-pressed to find an observant Jewish kid coming of age in the 90s who didn’t know his name. And the legacy of the failed rescue operation to bring home one of their boys, would haunt Israeli leaders for years.

So next up, a story that feels very familiar, but also very different…

Number 3: Elhanan Tannenbaum, 2004

Elhanan Tannenbaum wasn’t the most stand-up guy. I feel gross saying that, considering what he went through. But it’s true. When he wasn’t serving as a colonel in the IDF reserves, Tannenbaum was searching for his next shady deal — mainly revolving around drugs. And unlike the others on this list, he wasn’t a kid captured in the line of duty. He was a 54-year-old businessman in serious debt, who willingly flew to an enemy country under a fake passport to conduct what he thought would be a lucrative drug deal. He didn’t know that the guy arranging the deal — an Arab Israeli he’d known all his life — was working for Hezbollah. He certainly didn’t expect to be beaten with a club, sedated, packed in a crate, and sent to Lebanon, where he’d languish for over three years.

Israelis were… let’s say conflicted about Tannenbaum. Of course, no one particularly liked to think of how Hezbollah might treat an asthmatic 50-something Israeli Jew with deep knowledge of the IDF. But the wellspring of sympathy and support, the demonstrations, the bumper stickers – they were tellingly absent. Tannenbaum hadn’t been defending his country when he was taken. He’d willingly traveled under false pretenses to an enemy country to discuss his potential role in flooding Israel with drugs. He didn’t feel like Israel’s son. If anything, he was Israel’s slightly embarrassing sleazy uncle. I don’t remember an outcry about Tannenbaum. No bumper stickers. No mass protest.

And still, Israel paid a steep price for his safe return. In 2004, then-Prime Minister Ariel Sharon orchestrated a controversial prisoner swap for Tannenbaum, trading 435 Lebanese and Palestinian prisoners, as well as the remains of three deceased IDF soldiers held by Hezbollah. Many of the prisoners were convicted terrorists. And, most heartbreakingly, according to the head of the Mossad, the prisoners freed in the Tannenbaum swap went on to kill an additional two hundred and thirty one Israelis. Was this the price of Tannenbaum’s life? 231 Israelis, murdered by terrorists who should have been behind bars? It was a calculus that would dog Israel over the next few years, and especially during perhaps the best-publicized kidnapping case in Israel’s history.

Which of course, leads me to Story #4…

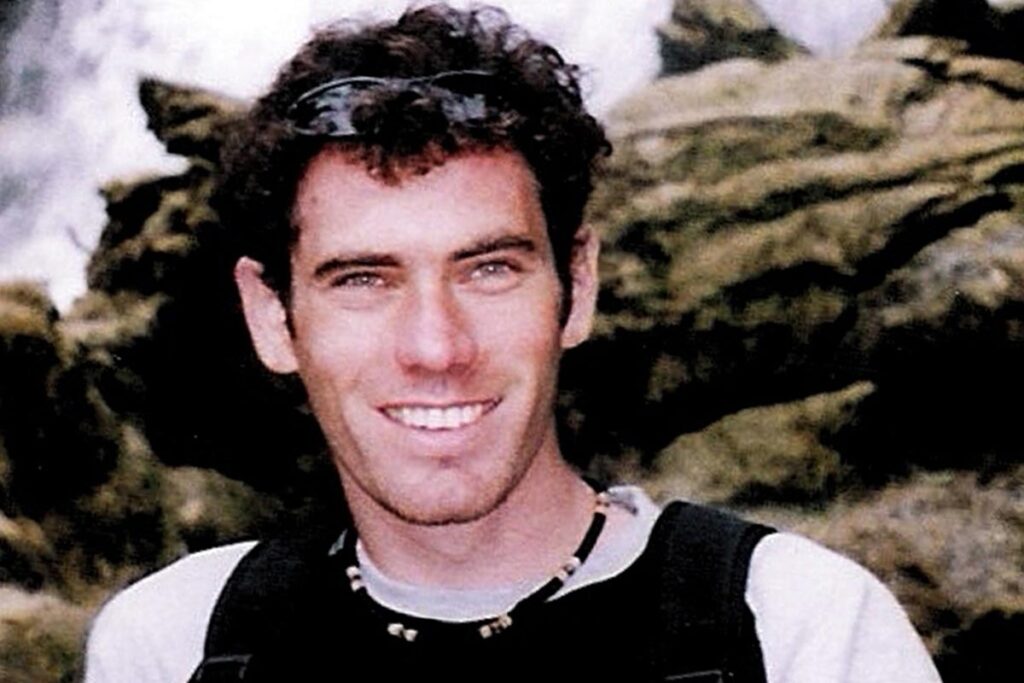

Number 4: Gilad Shalit, Ehud Goldwasser, and Eldad Regev, 2006

The summer of 2006 was a bad one for Israel. Just one year after the Jewish state unilaterally disengaged from Gaza — and yes, we have an episode on that, check it out — tensions were high on the border. Military intelligence suggested that Hamas was planning to abduct a soldier. But no one could have predicted that this abduction would be the first of three that summer, and that the nightmare would last for years.

June 25. An army base in southern Israel, close to the border with Gaza. The eight Palestinians who crossed underneath the fence separating Gaza from Israel took the base by surprise. They killed two soldiers, wounded 19-year-old Corporal Gilad Shalit, and dragged him to Gaza. His flak jacket was later found hanging on the fence through which he’d been dragged.

Israel retaliated immediately. Operation Summer Rains destroyed Gaza’s power station. Gaza was sealed, its neighborhoods ransacked. “Israeli tanks and armored infantry units massed near the border with the Gaza Strip today and intensive diplomatic efforts continued to try to gain the release of an Israeli soldier. 19-year-old Corporal Gilad Shalit was captured early Sunday in an attack on an Israeli border post by a group of militants, including members of Hamas, which now leads the Palestinian government.” But despite arresting dozens of Hamas operatives, Israel learned little of Shalit’s whereabouts.

As the southern border burned, the northern border simmered. Hezbollah, the Lebanese terror group, had no intention of letting Hamas have all the fun. “On the 12th of July, Hezbollah fighters infiltrated the order into northern Israel and ambushed an Israeli army patrol. In the attack, three Israeli soldiers were killed and two were captured. The captured soldiers were Ehud Goldwasser and Eldad Regev. Hezbollah quickly whisked them away into Lebanon.”

Are you keeping track?

There were eight names, now, on the dog tags. Zechariah. Yehuda. Zvi. Guy. Ron. Gilad. Ehud. Eldad. And this time, the abductions came with a death toll. Because aside from launching Operation Summer Rains in the south, Israel also responded to Hezbollah’s provocations in the north. With rockets pouring in from Gaza and Lebanon and three soldiers kidnapped, Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert needed a decisive response.

Hezbollah wanted to capture soldiers? Then Olmert would show them just how much those two lives would cost. The strategy, in his words, was simple: the boss has gone crazy. Here’s military analyst Yoav Limor explaining the rationale: “Hezbollah didn’t expect that Israel will go crazy, and it didn’t expect that Israel will begin a war.” Nasrallah threatened ‘We will destroy all the houses in Tel Aviv.’ But we heard of Hassan Nasrallah speaking later of miscalculations, and if he would have known, he wouldn’t have attacked Israel, etc. etc. He wouldn’t have kidnapped the two soldiers.”

But Hezbollah did capture the soldiers. And here’s the thing about the boss going crazy: sometimes, it doesn’t work. Hezbollah may have had their regrets at the end of the war. But Gilad, Eldad, and Ehud were still missing. And no one knew a thing about their status. Were they alive? Were they okay? It was the kind of uncertainty that the families of Zechariah and Yehuda and Zvi and Ron and Guy had been living with for decades. That punishing, crushing, rip-you-open-from-the-inside anxiety. That burning need to know.

And the entire nation felt it. The country seemed to mobilize within minutes. Gilad’s parents, Noam and Aviva Shalit, went from anonymous private citizens to the country’s biggest celebrities. Ehud’s wife Karnit shocked the world with her poise and determination, even traveling to the UN so she could accuse Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmedinijad of war crimes.

“My name is Karnit and I am the wife of Goldwasser, who was kidnapped by Hezbollah to Lebanon more than a year. You’re the responsible for this new bio support (?). I’m asking how come you’re not allowing the Red Cross to go and to visit them? How come you’re not sending us a sign of life more than a year? How come you’re not answering me?”

Ahmedinijad was silent. And after a bit of a kerfuffle in which the Iranian president ignored all questions that seemed even remotely pro-Israel, Karnit was escorted out by UN security.

The Goldwassers and the Regevs and the Shalits did everything they could. After two horrible, arduous years of back and forth with Hezbollah through a German intermediary, after meetings with world leaders and demonstrations at the UN and endless Facebook campaigns, Ehud and Eldad’s families had their answers. Unfortunately, they were sad ones. Because Ehud and Eldad were killed. They’d been dead since the start. The whole time that their families were agitating for their release, begging for a sign of life, they were unwittingly begging for bodies.

Bodies that came home in 2008, in exchange for five living Lebanese prisoners, as well as the remains of 200 Lebanese and Palestinian terrorists. (Yes: Israel keeps the corpses of prisoners too. You need leverage when you’re negotiating with terrorists.) Among these living Lebanese prisoners was Samir Kuntar, who we’ve talked about in another episode, obviously link in the show notes. This was a guy who, as a teenager, shot and drowned a young Israeli father and bludgeoned his four-year-old daughter to death with the butt of his pistol. And now, here he was, walking free.

Even in the Knesset, it was a controversial exchange. MK Yuval Steinitz publicly criticized the deal: “We are playing to the hands of our enemies…This is very much in favor of our enemies’ interest and it will encourage them in future cases.”

And whether you agree with Steinitz or not, there was some truth to what he was saying. Because three years after Ehud and Eldad came home, Israel signed another controversial deal, the most expensive one of all. In 2011, after five years of demonstrations and protests and rallies and negotiations, Gilad Shalit finally came back home alive. The price? You want to hear the price? Here’s the price: 1,027 prisoners, including many serving life sentences for murdering Israelis.

The heads of the Mossad and the Shin Bet had advocated strongly against the deal, compiling a report that showed that 45% of released prisoners resume their terrorist activities the moment they’re freed. Meir Dagan, the head of the Mossad, was particularly fervent, reminding anyone he could about the Tannenbaum deal that later cost the country 231 Israeli lives.

And yet, 79% of Israelis cheered the Shalit deal. Their boy was coming home. And I’m not embarrassed to tell you that I was just as overjoyed, just as relieved. When he was released, I found a livestream of his homecoming and stayed up all night to watch him come home, tears in my eyes. A decade later, the entire country cheered when he married his longtime girlfriend in the summer of 2021.

But Israelis weren’t the only ones cheering Gilad’s homecoming. Palestinians were watching closely. And they liked what they saw. Shalit had fetched a high price. Imagine what Israel would pay for the next abducted soldier, and the one after him, and the one after him.

A 2011 Telegraph article summarized the thought process nicely: quote, “For many Palestinians, particularly in Gaza, the release of so many prisoners for one man is evidence that Israel responds only to threats, making the path of peaceful negotiation espoused by Mahmoud Abbas, the president of the Palestinian Authority, and his moderate Fatah party nonsensical. ‘The people want a new Gilad, the people want a new Gilad,’ chanted the tens of thousands who gathered at a Hamas-sponsored rally in Gaza city to welcome home the freed prisoners.”

A decade after the prisoner exchange, Ashraf al-Ajrami, the former PA Minister of Prisoner Affairs, noted that “What happened in this Gilad Shalit deal with Hamas was the victory for the Palestinian people and also was a big achievement for Hamas movement.”

It’s an uncomfortable truth. I hate thinking about someone like Samir Kuntar going free, being greeted like some kind of conquering hero. And I hate thinking about the fact that Israel has an obvious weak spot. I’m not the only one.

In fact, all the way back in 1986, the IDF implemented a shadowy, controversial plan called the Hannibal Directive. But what does the suicide of a Carthaginian military commander from the second century BCE have to do with anything?

Well, the IDF’s Hannibal Directive – which is both shadowy and subject to constant amendment – is as follows. Do everything you can to avoid getting captured. If you see a comrade getting abducted, respond with force – even if you’re putting them at risk. All targets are legitimate if you’re trying to stop a kidnapping.

The logic of the directive is that a dead soldier is better than a captured one. There’s no ambiguity with a dead soldier. No agonizing anxiety about whether or not they’re alive. There’s no prospect of a dead soldier spilling state secrets. And there’s less pressure for a high-profile prisoner exchange. Trading terrorists for live soldiers? That’s tempting. Trading them for coffins? Less so. In fact, Hamas still has the bodies of two IDF soldiers, Hadar Goldin and Oron Shaul, killed in action in 2014.

But unsurprisingly, the Directive is controversial, and news of its existence only reached the public in 2003. No one wants to think about Israeli soldiers – brothers! – potentially killing one another rather than be taken hostage. And though IDF Chief of Staff Benny Gantz said in 2011 that the directive does not permit soldiers to kill one another, the directive is still mysterious and vague enough to be controversial. In fact, during the 2009 war between Hamas and the IDF, one commander instructed his troops:

“I don’t need to tell you this, but no soldier from the 51st battalion can be kidnapped, at any cost, not in any circumstance. That can mean that a soldier should detonate his hand grenade and blow himself up [together] with the person trying to abduct him.”

Hannibal Directive, indeed.

To this day, no soldier has been saved through the deployment of the Directive. So what’s the calculus here? Die rather than be taken alive? Get taken alive and later traded for hundreds or thousands of prisoners with blood on their hands? Get taken alive and languish for years? The Knesset understands how tangled and agonizing this calculus is, and how high the stakes. In 2014 — three years after Gilad came home — the Israeli Parliament voted 35-15 to stop these disproportionate prisoner swaps. It wasn’t personal. Everyone was relieved to have Gilad back home. But the IDF had just arrested sixty of the prisoners released in the Shalit deal. Israel was wasting resources, catching terrorists it had already put behind bars. Now, the law didn’t prohibit all prisoner swaps. But it did make it harder for the worst of the worst to go free. A prisoner serving a life sentence can no longer simply have his sentence cut short. To be considered for a prisoner exchange, he must have already served 15 years.

It doesn’t sound that prohibitive, right? But the law acknowledges that these disproportionate prisoner exchanges might be more damaging than helpful. That there’s a gray area here. Because where’s the line between ransoming a captive and giving in to a terrorist’s demand? Between saving one life and endangering so many others?

Some Jewish scholars point to the case of the Maharam, Rabbi Meir of Rothenburg, who was kidnapped by King Rudolf I of Habsburg in 1286. (Side note: weird thing for a king to do, right?) The king demanded an obscene amount of money for his release – and though the community would have been willing to pay for it, the Maharam point-blank refused. I’m not worth it, he said. We don’t ransom captives for more than they’re worth.

But how can you put a price on a human life? What is a single Israeli soldier “worth”? And who gets to decide that? Their mothers? Their fathers? Their husbands and wives? The government? The will of the people? The heads of the intelligence agencies, who calculate the risks of freeing terrorists? The Maharam decided his own worth for himself. He died in prison after nearly eight years in captivity. But Zechariah and Yehuda and Zvi and Ron and Guy and Gilad and Ehud and Eldad — they didn’t get to decide.

And neither do Avera Mengistu or Hisham al-Syed.

Uhhh…. Who, you ask?

Well, they’re the fly in the ointment. The wrinkle in the story. Because, you see, there are two more living Israelis being held captive in Gaza. Avera Mengistu was 28 years old when he crossed voluntarily into Gaza. Israeli soldiers watched him go and assumed he was an African refugee — perhaps from Eritrea or Sudan — sick of life in Israel. But Mengistu is a Jew. He is Black. He is poor. He is deeply mentally ill. And he is being held in Gaza under unknown conditions. And like Mengistu, al-Syed was a mentally ill man in his 20s when he crossed voluntarily into Gaza in 2015. And like Mengistu, al-Syed is a minority in Israel: a Bedouin citizen.

A cynic might note the discrepancies between these cases and those of Zecharia and Yehuda and Zvi and Ron and Guy and Gilad and Ehud and Eldad. Some might say that the others are white. At least two have dual citizenship — Zechariah is an American; Gilad French. Could the government be neglecting the cases of Mengistu and al-Syed due to their demographics?

But a less cynical person might point out that Mengistu and al-Syed wandered into Gaza of their own accord. That they weren’t kidnapped soldiers. Like Elhanan, and unlike the others, they did this to themselves. Both had been exempted from the army — Mengistu because of his mental health issues; al-Syed because he is Arab. And both had a long history of mental-health concerns. Of leaving their homes for days on end without a word to anyone. No one forced them into a dangerous position. No one sent them to fight a war or patrol a border, knowing they might not come back.

While some have accused Israel of racism and neglect, I think that’s a less-than-fair take. To start, the Israeli government has negotiated with Hamas to bring home Mengistu and al-Syed. The deals have fallen through — just like the first few iterations of the Shalit deal. As to why the Israeli public hasn’t rallied behind their cause? Well, it’s the same reason that no one was printing out bumper stickers that screamed “bring Elhanan Tannenbaum back.”

Tannenbaum, Mengistu, and al-Syed were the architects of their own captivity. That doesn’t mean they deserve to be held captive, god forbid. But it does explain the attitude of the general public, I think. Because I genuinely believe that Mengistu and al-Syed were of sound mind, if they’d been captured as soldiers, their names and faces would be plastered everywhere in Israel. And — again and again — it’s proven itself more than willing to make ridiculous sacrifices for even a scrap of news about captured soldiers, including mounting a Mossad fact-finding mission in 2019 to gain some information about Ron Arad. 2019! That’s 33 years after his capture! Because every soldier is one of “our boys.” And Israel will do anything to get them back.

So that’s the story of captured soldiers, and here are your five fast facts.

- Pidyon shvuim, or the ransom of captives, is considered a “great mitzvah.” And yet, over the centuries, Jewish scholars have debated whether it’s appropriate to pay an exorbitant ransom for a captive.

- But this isn’t a theoretical question. The official policy of the State of Israel reads “The Government will do everything in its power to secure the release of POW’s and MIA’s… and to bring them home.”

- The Israeli government doesn’t negotiate with terrorists… unless it does. The government has negotiated the return of POWs with enemy states since the War of Liberation in 1948. And terrorist groups know that Israel is definitely willing to do, shall we say, disproportionate exchanges.

- Over the years, Israel has released thousands of prisoners, including convicted terrorists, to get back captives. The most famous of these is Gilad Shalit, abducted by Hamas in 2005 and held until 2011.

- Critics have pointed out that the policy only further encourages terror, and argue that the Israeli government should not make policy decisions based on emotion. Still, nearly 80% of Israelis believe that the government should ransom captives at any cost. Because for better or worse, the Jewish people are a family. And you’ll do anything to get back your family.

Those are the five fast facts, but here’s one lesson as I see it.

If you’ve ever been to a shabbaton, and even if you haven’t, just hear me out, you know that eventually, after the sun has gone down on Saturday night, there’s a strong chance that someone’s gonna pulls out a guitar and start strumming the opening chords of the Jewish summer camp classics. Ba’Shana HaBa’a. Kol Ha’Olam Kulo. A little Tov le’hodot. Maybe Al Kol Eleh. And inevitably, when everyone is feeling sentimental and a little high on life, they loop their arms around each other’s shoulders and start swaying to the minor-key refrain of Acheinu. I’ll spare you my singing, but here’s a beautiful version:

אַחֵינוּ כָּל בֵּית יִשְׂרָאֵל, הַנְּתוּנִים בְּצָרָה וּבַשִּׁבְיָה, הָעוֹמְדִים בֵּין בַּיָּם וּבֵין בַּיַּבָּשָׁה, הַמָּקוֹם יְרַחֵם עֲלֵיהֶם, וְיוֹצִיאֵם מִצָּרָה לִרְוָחָה, וּמֵאֲפֵלָה לְאוֹרָה, וּמִשִּׁעְבּוּד לִגְאֻלָּה, הַשְׁתָּא בַּעֲגָלָא וּבִזְמַן קָרִיב.

Our brothers, the whole house of Israel, who are in trouble or captivity, whether on sea or on dryland, may God have mercy on them and bring them from distress to comfort, from darkness to light, from slavery to redemption, now, quickly, and soon. Let’s say Amen.

And that song — no matter who is singing it or where — encapsulates this episode. It’s in that first word. Acheinu. Our brothers and sisters. That means the entire house of Israel, regardless of language or culture, skin color or socioeconomic status or political affiliation. This sentiment is encoded in our Torah, the Hebrew Bible: Love your neighbor as yourself. Don’t be jerks to each other. (That’s a loose translation.) The book of Exodus even describes how the Jewish people accepted the Torah “as one,” “with one voice.” And that’s because, as the Talmud tells us: All of Israel is as a single soul. All of Israel is responsible for one another.

And now, for the first time in two thousand years, that sentiment has institutional backing. The State of Israel was established as a safe haven for any Jew in distress! And as we talk about often, the Jewish state takes its responsibility seriously, risking Israeli lives to rescue Jews in danger. The Mossad has flown to Uganda to rescue Jewish hostages. Airlifted Jews from Yemen and Ethiopia. Launched a series of revenge attacks for the murder of Jewish athletes at the 1972 Munich Olympics. Israeli volunteers have flown to the Ukrainian border to help get Ukrainian refugees to Israel.

But… why? After all, Israel is a secular country. It isn’t bound by Biblical injunctions. And let’s face it: these missions are dangerous and expensive. So why would the state go to such lengths to help Jews across the world? Why would the army or the intelligence services endanger its people to rescue a single hostage? Why would the government free thousands of terrorists just to get back one young soldier?

I’ve been thinking a lot about this question. And all I can offer is my own take which I learned from my barbers, Avi and Alon. Two Israeli guys living in South Florida. We end up shmoozing every time I’m in there. I tell them what I’m researching for this podcast. They politely try not to laugh at my Americanized Hebrew accent and teach me new slang words. It’s beautiful. And I was curious. I wondered if maybe I was exaggerating. Wondering if I was really telling the truth when I say things like Israelis are all family. So I asked them. Avi. Alon. What do you think about the prisoner exchanges? Do you think we should have given up this many prisoners just to get Gilad back?

They looked at me like I was insane. Honestly, I’m glad the haircut was over at that point, because that could have gone really badly for me. And finally, they answered, in this tone of affectionate disbelief, like, check out the idiot American. As though they were telling me the most obvious thing in the world. Achi! Hem achim! Bro. They’re our brothers.

And that was it. That was my answer. I wasn’t sentimentalizing. I wasn’t telling myself some cute story. These were Israelis who had left their home. Who had chosen, for whatever reason, to make their lives elsewhere. And yet, across thousands of miles, they felt it. They’re our brothers. So we’ll do whatever it takes. Acheinu, kol beit yisrael.