With Israelis arguing over everything from the judicial overhaul to the separation of religion and state, some Israelis have started wondering if it’s time to split up.

A proposal currently on the fringes of political discussions would have the State of Israel split into two: one liberal, secular state called Israel, and one religious, traditional state called Judah.

While the idea is only being promoted by a relatively small number of Israelis, it has sparked a slew of op-eds and public polls examining the idea.

So, is this the magic solution? Do Israelis need to shake hands and split?

To understand both the proposal and fears of such a divide, we first need to journey back nearly 3,000 years to the era of the first Israelite kingdom.

Judea and Israel: Two nations, one people

After the Israelites entered the Land of Canaan under Joshua, they remained largely tribal. They occasionally coalesced under the leadership of various judges and, a few centuries later, unified significantly under King Saul.

The people remained relatively united (despite temporary rebellions and unrest) under King David and King Solomon. However, the dynamics shifted dramatically when Solomon’s son, Rehoboam, took power.

Upon his coronation, the people implored Rehoboam to reduce the heavy taxes imposed by his father. Ignoring the wise counsel of his elders to yield to the people, Rehoboam instead decided to do the opposite and raise the taxes even more.

This decision sparked widespread discontent with the people crying out, “We have no portion in David!” They chose Jeroboam — who had been told by a prophet that he would lead a split-off kingdom after Solomon — as their king.

Subsequently, 10 of the 12 tribes rallied around Jeroboam, creating the Northern Kingdom of Israel. Conversely, Judah, Benjamin, and segments of the Levi tribe stayed loyal to Rehoboam, forming the Southern Kingdom of Judah.

Jeroboam took immediate steps to sever ties between the two kingdoms. He introduced golden calves for worship within his kingdom and erected barriers to prevent pilgrimages to the Temple in Jerusalem.

The results were tragic. Both kingdoms were marred by extensive periods of unrest and domination by neighboring empires, and the practice of idol worship spread throughout the two kingdoms.

Approximately 200 years after it was formed, the Northern Kingdom fell to the Assyrians. Most of its inhabitants, representing 10 of the original tribes, were dispersed among other nations and lost their distinct identity over time. These 10 tribes are now commonly referred to as the “Lost Tribes.”

Roughly 130 years after the Northern Kingdom’s fall, the Babylonians conquered the Southern Kingdom. This devastating event marked the end of the first Temple era and propelled the Jewish people into a 70-year exile, culminating in the construction of Second Temple.

So, what brings these ancient kingdoms into the spotlight in 2023?

Is Israel the Jewish State or the State of the Jews?

Ever since early Zionists first conceptualized the modern state of Israel, and especially after its establishment in 1948, there has been an ongoing debate about the identity of the Jewish homeland.

Present-day Jewish Israeli society is generally split into four main groups: secular, traditional, religious Zionist (similar, but not identical, to America’s Modern Orthodox), and Haredi. Opinions about the essence of the Jewish state and the nature of Judaism often align with these categories, though the boundaries between them can sometimes blur.

Central to this debate in Israeli society are the questions surrounding religious, cultural, and ethnic divides. The crux of the matter is often distilled into “Is Israel the Jewish State or the State of the Jews?”

In other words, should Israel be a state where the public sphere is guided by halakha (traditional Jewish law), or should it be a state where Jewish and non-Jewish citizens decide what the public sphere looks like without needing to follow Jewish law?

Highlighting this dilemma, a recent survey by the Jewish People Policy Institute in Jerusalem (JPPI) found that most Israelis (62%) interpret the term “Jewish state” as a state for the Jewish people.

Yet, diving deeper into the religious affiliations, a quarter of religious Jews and 44% of Haredi Jews view the term as denoting a state for the Jewish religion.

The survey also found a perception divide: most secular Jews feel that there is significant religious coercion in Israel, while about 61% of Haredim perceive significant secular coercion. Interestingly, both groups perceive minimal coercion from their own side (for instance, 61% of secular Jews believe there is little to no secular coercion in Israel).

How Judaism is defined is also debated among Israelis. According to JPPI’s Israeli Judaism poll, 43% of Israelis see Judaism mainly as a religion, 26% view it as a nation, 20% perceive it as a culture, and 10% consider it an ancestral lineage.

Recent contentious issues — such as the judicial overhaul, discussions about whether public transportation should run on Shabbat, debates over educational curriculum content, and whether to extend draft exemptions for Haredi yeshiva students — have brought these complex societal tensions to the surface.

Should Israel get a divorce?

As Israel grapples with existential questions regarding its identity, some Israelis at the margins of political discourse are asking whether it is time for a parting of ways.

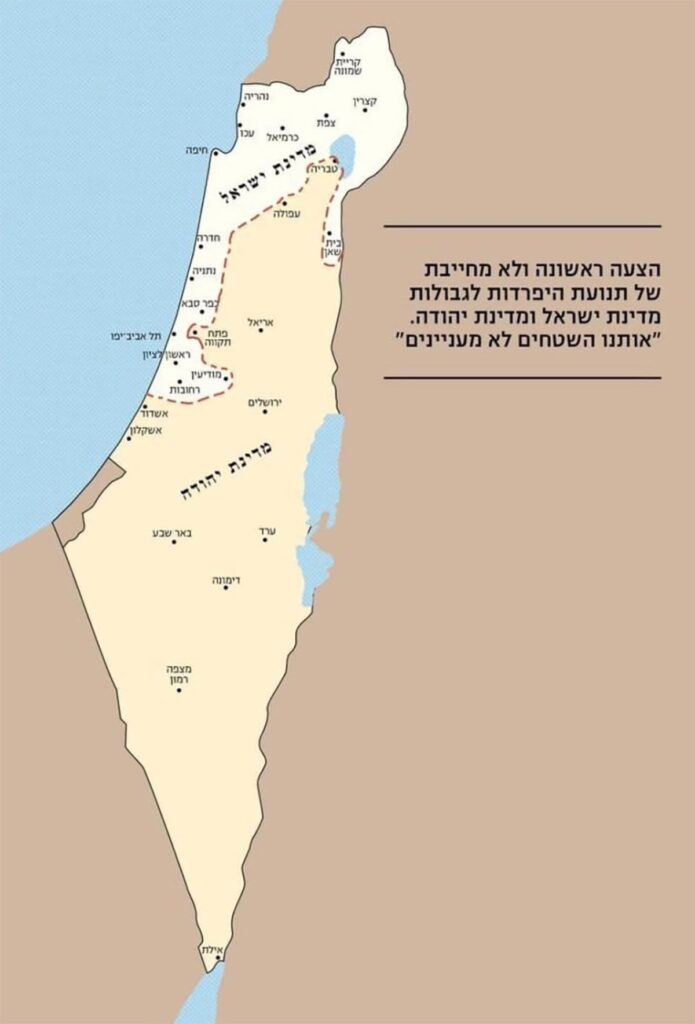

A budding faction calling themselves the “Separation Movement” has risen amid the crisis, proposing a division where “Israel” encompasses the center and north, while “Judah” would claim the remainder of the country and the West Bank.

Concurrently, other proposals have surfaced, suggesting federations comprised of multiple states bound by a central parliament.

The talk of separating isn’t entirely new in Israeli discourse. It has previously appeared in Israeli media, most notably through the miniseries “Autonomies.” This production envisioned a dystopia where Israel is bifurcated by a steel barrier, resulting in a secular State of Israel headquartered in Tel Aviv and a Haredi Autonomy based in Jerusalem.

The provocative miniseries stirred profound debates within Israeli society. For many, the depicted scenario was a bleak, dystopian version of what continued societal tensions could lead to. Yet, a Haaretz op-ed speculated if such a division could actually offer a remedy to Israel’s internal schisms.

Additionally, on Israel’s Independence Day this year, the political satire show “Eretz Nehederet” (“A Wonderful Land”) envisioned what it would be like if the opposition and coalition held separate Independence Day torch-lighting ceremonies.

Eyal Kitzis, the show’s host, expressed disbelief: “Look at the situation you all have led us to. We’re so not united that we’re not even able to celebrate our independence together.”

Dramatically, the two sides then proclaim the inception of two new countries: the “State of Isra” and the “Kingdom of El.” Each new country adopted half of the Star of David for their flags, with a barbed wire fence delineating their territories.

This tongue-in-cheek portrayal elicited a mix of laughter and reflection from Kitzis, the live audience, and Israelis.

Where do we go from here?

The current tensions are not the first time the modern State of Israel has faced fundamental questions of identity, and it most certainly won’t be the last. So, where do we go from here?

In the early days of the state, the IDF faced a dilemma: how to protect the ability of religious soldiers to follow their religion while also ensuring the freedoms of secular soldiers.

The issue came to a head with the “Case of the Cooks.” In this incident during the War of Independence, two IDF cooks refused an order to prepare a meal on Shabbat. The two were tried and convicted for insubordination and sent to military prison.

The incident sparked outrage among religious Israelis. Then-Religious Affairs Minister Rabbi Yehuda Leib Maimon resigned from the government, arguing that such an army is unfit to be a Jewish army.

As religious and secular leaders convened to seek a solution, both sides began to support a proposal in which religious soldiers would only serve in religious units, and secular soldiers would only serve in secular units.

Rabbi Shlomo Goren, the IDF’s inaugural first chief rabbi, vehemently opposed this idea, arguing that it would erode the army’s Jewish essence. In the end, Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, recognizing the importance of maintaining a cohesive IDF in that moment, concurred with Goren’s perspective.

Fast forward to the present, it seems many Israelis agree with Goren as well.

According to the Israel Democracy Institute’s Israeli Voice Index for May, an overwhelming majority (73%) of Israelis oppose the idea of dividing the country into two states. Over half responded that they were “strongly opposed.” Additional recent polls found similar results.

In his book, “Impossible Takes Longer,” Daniel Gordis wrote that, in recent decades, the Israeli public increasingly agrees on harmonizing secular nationalism and Jewish tradition. Even predominantly secular Israelis often engage with Jewish traditions, whether through cultural engagement, education, or observance of holidays.

Most Israeli Jews identify as secular, but widespread practices like the Passover seder and the observance of Yom Kippur point toward a shared understanding.

In the closing of his book, published as the judicial reform controversy escalated, Gordis wrote:

“Israel… was born out of contradictions, and it will likely remain a bundle of contradictions. Strange though it may sound, I believe that, to survive, Israel needs to celebrate those contradictions. For they are what make Israel both fascinating and resilient.”

Originally Published Aug 31, 2023 05:06PM EDT