Listen to this article

Editor’s Note: This is a breaking news story and has been updated to reflect the developments of Jan. 19, 2022.

Depending on the headlines you are reading, you either are hearing that Sheikh Jarrah is:

- An illegal land grab by Jewish settlers

- An ethnic cleansing of Palestinians by Israel

Or:

- The eviction of illegal squatters by Israel

- Jews reclaim their neighborhood which has always been rightfully theirs

Both sides seem to be in agreement on one thing: the fate of this neighborhood has become a flashpoint moment for Palestinian and Jewish rights in Jerusalem.

Related: How to talk about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict with your friends

But first, what’s the latest?

Overnight on January 18th, 2022, Israeli police demolished a home that was on property slated by the Jerusalem Municipality to become an Arab school.

כך פותחים את הבוקר בשיח' גראח. החלה הריסת הבית של מחמוד סאלחייה לאחר שכוחות גדולים פשטו על הבית בשלוש לפנות בוקר והוציאו את בני המשפחה. עוד בוקר קשה בשיח' ג'ראח. pic.twitter.com/p6ga4JBEse

— Jack khoury.جاك خوري (@KhJacki) January 19, 2022

The family claims that they purchased the property after they fled from the western Jerusalem neighborhood of Ein Kerem during the 1948 War of Independence but had not yet registered it with the Jordanian authorities prior to the Six Day War in 1967. Such registration was not possible once Israel annexed the city from Jordan after the war.

According to Israeli media, police raided the house around 3:30 A.M. and evicted the family and activists staying with them. At least 18 people were arrested, according to an attorney who represents the family. Many of the detained were released hours later.

A year ago, a Jerusalem district court judge ruled in favor of the city and allowed the eviction to proceed. The city maintains that the family is squatting illegally on the land.

It’s more complicated than flashy headlines

Boiled down, the situation in this small East Jerusalem neighborhood is a property rights battle in an area that has changed hands many times.

In order to better understand the politics, emotions, and legality of what is happening in Sheikh Jarrah, we need to start from the beginning. It actually is important to look back at the history of this neighborhood because what happened thousands of years ago is playing out in real time today. In fact, property records dating back to the Ottoman Empire have been used to settle parts of this dispute already.

What other court cases are taking place?

Israel’s Supreme Court heard the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood case on Monday, August 2, 2021, and basically sent the case back to arbitration. That ruling stated that there would be no immediate evictions as the court has ruled that the two parties still need to iron out the details of the land’s ownership.

תראו מה קורה בחוץ pic.twitter.com/o7dSWSLqzL

— نير حسون Nir Hasson ניר חסון (@nirhasson) August 2, 2021

According to a proposed compromise made by the court, the Palestinians living in the neighborhood would be given “protected status” and not evicted. They would then have to pay a small rent fee to a settlers’ association that obtained the rights to the land in the 1980s.

A 1970 Israeli law is at the center of the legal debate over the evictions of the 58 Palestinians. The law gives Jewish Israelis the right to reclaim East Jerusalem properties that were once owned by Jews before 1948, as long as they could show proof of ownership or expulsion by the British or Jordanians. Palestinians who lost their land do not have the same legal right to sue for property lost after the war.

In 1972, the Sephardic Community Committee (which previously owned the tomb of Shimon Hatzadik) first sued for ownership over a property in the neighborhood, and the court ruled in their favor in 1976.

Then in 1982, residents signed a legal agreement that allowed them to remain in a Sheikh Jarrah property as long as their status changed from owner to tenant and that they would pay rent. Since then, the Palestinian signers say they were coerced into signing and no longer recognize the agreement. This agreement was at the center of the Supreme Court’s ruling on Aug. 2nd.

The families at the center of the Supreme Court case were reportedly offered a similar deal by Jewish developers but that was turned down. The offer allowed the Palestinians to stay in their homes paying rent as long as the signee was alive.

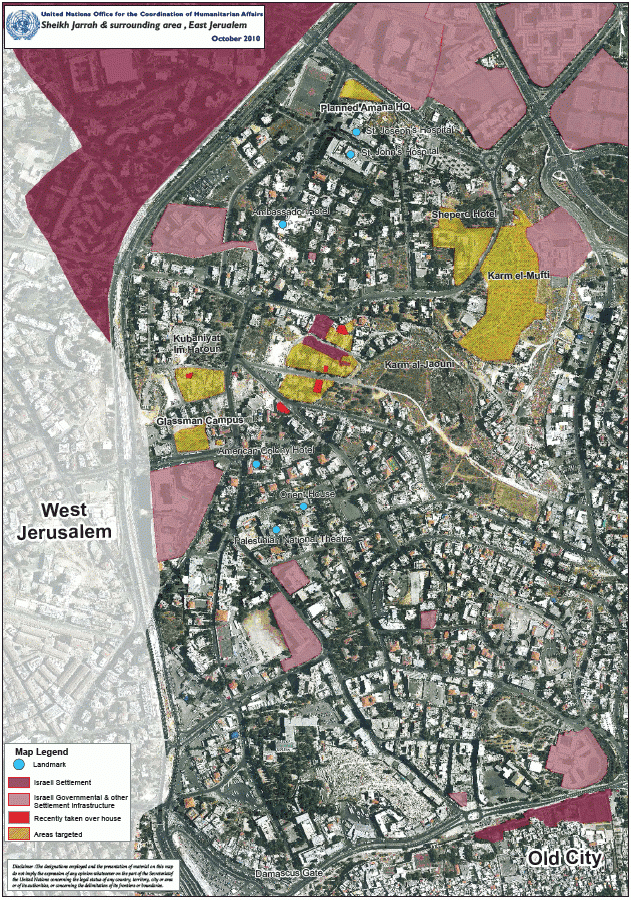

Sheikh Jarrah shot into the international spotlight in the 2000s when Israeli courts ordered the evictions of three Palestinian families following a series of lawsuits. There have been no court ordered evictions since 2009, but new cases have been making their way through the legal system like the current case that is making headlines.

In May the Israeli Supreme Court delayed its decision by a month, saying that it will honor a Palestinian request asking for Israel’s attorney general to weigh in on the case.

Israel’s attorney general notified the country’s Supreme Court in June that he will not intervene in the decision surrounding evictions.

“In view of the many legal proceedings conducted over the years in relation to the real estate at the center of the dispute, the attorney-general came to the general conclusion that there is no room for him to appear in the proceedings,” a statement from the office of Avichai Mandelblit said. His office went on to say that the case was “too weak” adding that his legal opinion would not be able to prevent the evictions.

The Supreme Court’s ruling now puts the legal dispute back in the hands of the two parties involved (Jewish and Palestinian). The court will review the developments of the case in the future, however no date has been set.

Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood

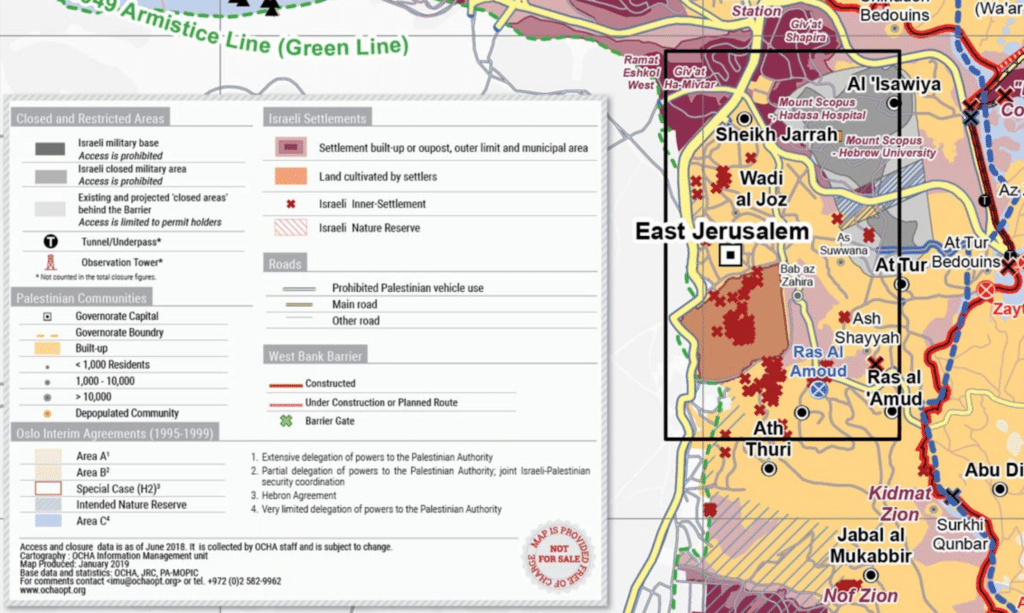

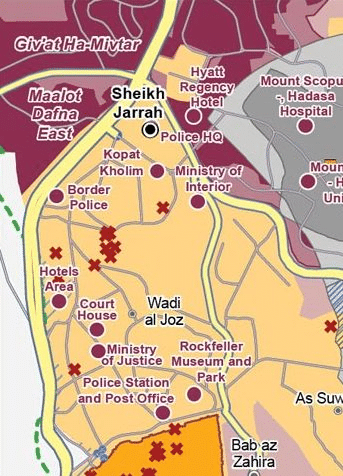

Today, Sheikh Jarrah is a predominantly Palestinian neighborhood in East Jerusalem roughly a mile (or 2 kilometers) away from the Old City. Currently 3,000 people call the neighborhood home.

Here’s where it gets complicated and where history plays an important role in today’s debate over the evictions of 58 people.

The neighborhood is old, ancient in fact, with the first records showing up in the 12th century. Historians say for thousands of years there has been a permanent Jewish presence living in Sheikh Jarrah next to the tomb of Shimon Hatzadik (also known as Simeon the Just) who was a Jewish High Priest during the time of the Second Temple (he died in the 3rd century BCE). Many Jews until today refer to the neighborhood as Shimon Hatzadik. His tomb and the surrounding compound was actually purchased in 1875 by the Sephardic Community Committee and the Ashkenazi Assembly of Israel.

Now fast forward to the 1900s. In 1905, an Ottoman census that included Sheikh Jarrah and its surrounding areas found 97 Jewish families living in the area alongside 167 Muslim and six Christian families.

Following Israel’s War of Independence in 1948, the Jewish population was expelled from Sheikh Jarrah since the area fell on the Jordanian side of the new border.

Eight years later, in 1956, Jordan relocated 28 Palestinian families who were displaced during Israel’s War of Independence to Sheikh Jarrah. The move was approved by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA), and the organization stipulated that the families would be given ownership of their homes after three years which would then end their refugee status. The Jordanian government never did formally transfer over the property rights to the Palestinians.

By the 1950s Sheikh Jarrah had changed hands several times from Ottoman rule, to British Rule, to Jordanian rule, to Jordanian rule with assistance by UNRWA which was in part stipulating property rights in the area. By this time the Jewish population, which had been documented living there for thousands of years, had completely moved out or was expelled and a Palestinian population had moved in or was relocated to the neighborhood.

Enter 1967. Nineteen years after 1948, East Jerusalem (including Sheikh Jarrah) came under Israeli control following the end of the Six Day War. Since then, the international community considers the area occupied by Israel which claims authority over the region.

Sheikh Jarrah and East Jerusalem

East Jerusalem’s Arab population has grown from an estimated 44,000 in 1967 to 327,700 in 2016. Only a few hundred Jews were left in other East Jerusalem neighborhoods in 1967 due to their expulsion in 1948. In 2016, the Jewish population of East Jerusalem was listed as 214,600.

In 1967 and 1981, Israel offered Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem the right to apply for citizenship. However, the vast majority of the people declined. Today East Jerusalem residents fall under the jurisdiction of the Israeli government and have “resident status,” but not full citizenship (95% of East Jerusalem’s residents do not have citizenship status). There are paths to full citizenship, but critics say that Israel makes it extremely difficult to achieve. Israel says the process is improving, citing increasing numbers of applicants and approvals (in 2016, seven out of 1,081 requests were approved; and in 2018, 353 out of 1,012 were approved).

Sheikh Jarrah residents, like all East Jerusalem residents, pay Israeli taxes and receive social security benefits and state healthcare among other things. In 1980, Israel annexed East Jerusalem placing the area under the law, jurisdiction and administration of the state.

Political tension

The UNRWA says the majority of the Palestinians under threat of eviction were relocated to Sheikh Jarrah under a sponsored housing scheme in 1956. A spokesman for the U.N. high commissioner issued the following statement:

“In practice, the implementation of these laws facilitates the transfer by Israel of its population into occupied east Jerusalem. The transfer of parts of an occupying power’s civilian population into the territory that it occupies is prohibited under international humanitarian law and may amount to a war crime.”

In a televised statement, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu responded to the criticism:

“Jerusalem is Israel’s capital, and just as every nation builds in its capital and builds up its capital, we also have the right to build in Jerusalem and to build up Jerusalem. That is what we have done and that is what we will continue to do.”

Jerusalem City Council member Yonatan Yosef, a resident of Sheikh Jarrah, told The Times of Israel:

“For me, history begins thousands of years ago, when Shimon Hatzadik was buried there. Shimon Hatzadik was a Jewish neighborhood, is a Jewish neighborhood and will stay Jewish.”

The European Union and the United States have also expressed concerns over the case and the rising tensions in the region.

Rising tension

Since the last eviction in 2009, there have been steady protests in East Jerusalem and Sheikh Jarrah — by both Israeli and Palestinian activists — over the evictions. At their peak in 2011, thousands were taking part in demonstrations after Friday prayers.

After nearly a decade of quiet, the situation has since escalated with tensions reaching a boiling point ahead of the expected Supreme Court ruling.

75,000 worshippers at Al Aqsa Mosque during holiest night of Ramadan, Laylat al-Qadr.

— لينة (@LinahAlsaafin) May 8, 2021

Thousands of Palestinians in 48 made their way to Jerusalem, were initially stopped by Israeli police so many of them decided to walk. Others forced the roads open خاوة pic.twitter.com/ba1TNF1vrv

Friday night worshippers left the Al Aqsa mosque complex chanting “bomb Tel Aviv” and clashed heavily with police in some of the city’s worst violence in years. More than 200 Palestinians and 17 Israeli police officers were wounded. Officials estimate that 90,000 people attended evening prayers that night.

Former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert told Israeli news outlet Kan the following day that “a kind of intifada is brewing, which is possible to prevent.”

Saturday night there were more riots by Palestinians following evening prays at Al Aqsa mosque and more than 100 were injured.

A senior Hamas official tweeted over the weekend: “We salute the people of al-Aqsa, who oppose the arrogance of the Zionists, and we call on our people in Palestine to support their brothers by all means.”

Hamas has also responded by firing several rockets into Israel from Gaza and setting fire to several areas in the south of Israel.

Israeli officials also say that they thwarted a “major attack” by terrorists in the West Bank on Friday. Two out of three suspects were killed after they opened fire toward a Border Police officer. Earlier in the week, a 19 year old Jewish teen Yehuda Guetta was killed, and two others were seriously injured (they were also 19), in a driveby shooting in the West Bank.

On Monday morning, clashes continued on the Temple Mount after thousands of Palestinians gathered at the holy site overnight while collecting rocks and other weapons. Over 300 Palestinians, as well as 21 police officers, were reported wounded in the clashes. The Temple Mount was closed to Jews as a result, and a Jewish Israeli reportedly survived an attempted lynching outside the Lions Gate of the Old City after being attacked by a mob of Palestinians.

This afternoon, Hamas issued an ultimatum that if Israeli security forces didn’t leave the Temple Mount and Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood by 6 p.m., it would attack Israel. Just after 6 p.m. Hamas launched seven rockets towards Jerusalem and Beit Shemesh, forcing thousands of Israelis to run to bomb shelters, including those marching in the Flag March in Jerusalem while celebrating Jerusalem Day. Hamas also fired a barrage of rockets toward Ashkelon and communities surrounding the Gaza Strip. Israel responded by attacking Hamas targets in northern Gaza. Islamic Jihad has threatened to resume the firing. This is a developing story.

Related Story: Why did this start? We answer your questions on what’s going on in Israel

Concluding thoughts

If you’ve been watching the news or reading the stories online, you’ll notice that flags are one piece of this very complicated story. During the Friday night clashes at Al Aqsa, Palestinian and Hamas flags were seen waving in the air. Right below the complex, Jewish worshippers were seen at the Western Wall under the glow of Israeli flags dotting the area. And last week, while Palestinian residents of Shiekh Jarrah were meeting for nightly iftars (the traditional break fast meal held during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan), Jewish extremists entered the neighborhood waving Israeli flags. Israeli police had to shut down the area due to the clashes that followed.

This is not a question of moral equivalence, and we are not political pundits and commentators. We’re educators and journalists who look for symbolism, asking our students and our readers to make meaning out of symbolism. That’s why we’re concluding with this poem by the famous Israeli poet, Yehuda Amichai, who writes about Jerusalem and its many flags. This Jerusalem Day, may we draw some inspiration from Yehuda Amichai’s words in his poem titled “Jerusalem.”

Jerusalem Yehuda Amichai On a roof in the Old City laundry hanging in the late afternoon sunlight the white sheet of a woman who is my enemy, the towel of a man who is my enemy, to wipe off the sweat of his brow. In the sky of the Old City a kite At the other end of the string, a child I can't see because of the wall. We have put up many flags, They have put up many flags. To make us think that they're happy To make them think that we're happy.

@jewishunpacked ASK US ANYTHING about Israel-Palestine! Veteran journalist will be answering questions all day + unpacking the latest. ##BreakingNews ##Israel ##MidEast

♬ Hope (feat. Faith Evans) – Twista

Originally Published May 10, 2021 09:04AM EDT