I’m a dad. And a nerd. And I host a history podcast, so you know I love a dated reference. Which might explain why I’m opening this episode with an Israeli pop song from two decades ago. The pointed social commentary of funk band Hadag Nachash seems doomed to be eternally relevant (seriously, check ’em out – we’ve linked some cool stuff in the show notes and one of their lead guys, Sha’anan Street is seriously cool.)

Their 2003 song “Misparim,” Numbers, catalogs some of Israel’s most relevant stats. Including a number that is deeply, tragically familiar to Jewish people everywhere.

ועדיין המספר הכי גדול עד היום

שמגלם את התקווה אבל ממחיש את האסון

הוא זה שכשאומרים אותו

כל אדם שפוי עובר לדום הוא שש מיליון

Translated, that means something like: The biggest number till today – that embodies the hope yet illustrates the catastrophe – is the number that makes every sane person stand still – six million. Okay, it sounds a lot better in Hebrew. But even in English, the message is powerful. Because every Israeli, and I’d wager most Jewish people, knows what this number means. One-third of global Jewry, erased in under a decade, gone.

This kind of collective remembering isn’t an accident, and it isn’t spontaneous. Jewish institutions – including the Israeli government – have gone to great lengths to cultivate a collective Holocaust consciousness. And I’m prepared to bet that many of you, listening, have been on the receiving end of those efforts. That you’ve been to a Holocaust museum at least once, or heard a survivor give a speech, or maybe even visited a death camp.

And yet, I feel reasonably confident that if I asked your average affiliated (hate that term) Jewish millennial what they know about the Holocaust, few would mention John Demjanjuk, and if I asked 100 people about the “famous trial” where Israel tried a Nazi war criminal, 99 of them would mention Eichmann, not Demjanjuk. And it’s fair; I mean, I hadn’t heard of him until 2019, when Netflix released a documentary series called “The Devil Next Door,” and I do Jewish education for a living. I really recommend that documentary, by the way. It was a helpful resource for our team as we put together this episode. Because like it’s much better-known counterpart, the Eichmann trial, this almost-forgotten episode of Israeli history ignited an incredibly important conversation about Holocaust consciousness, memory, forgiveness, and justice.

Why does this story matter – especially in an episode of a show about Israeli history?

And to get inside my head, one thing I kept wondering about is, in researching and thinking about John Demjanjuk and his trial: what really is justice?

One more introductory note from me as we get into this story. My psyche is divided in half. Half of me is energized to tell this story. The Holocaust has caused inner turmoil of epic proportions for generations of people. Holocaust movie after Holocaust movie is produced, trips to Holocaust museums are mandatory in some places, and Holocaust education remains critical to understanding Jewish identity today.

And yet, and yet! How sad this is, not just because shaping an identity that is based on how others perceive you and treat you is the surest way to insecurity, and not just because a positive affirmation, a positive identity, that is not morbid or death centered is so much, well, healthier, but also because there is much of Jewish history that is not merely defined by non-Jews hating Jews. And when we focus exclusively on the Holocaust or antisemitism, I think it misses part of the picture, and therefore, part of our identities are not formed in healthy or complete ways.

I hope that made sense, and I think it’s worth keeping in mind. But for now, let’s get to the story of an ordinary Joe, or ordinary John in this case.

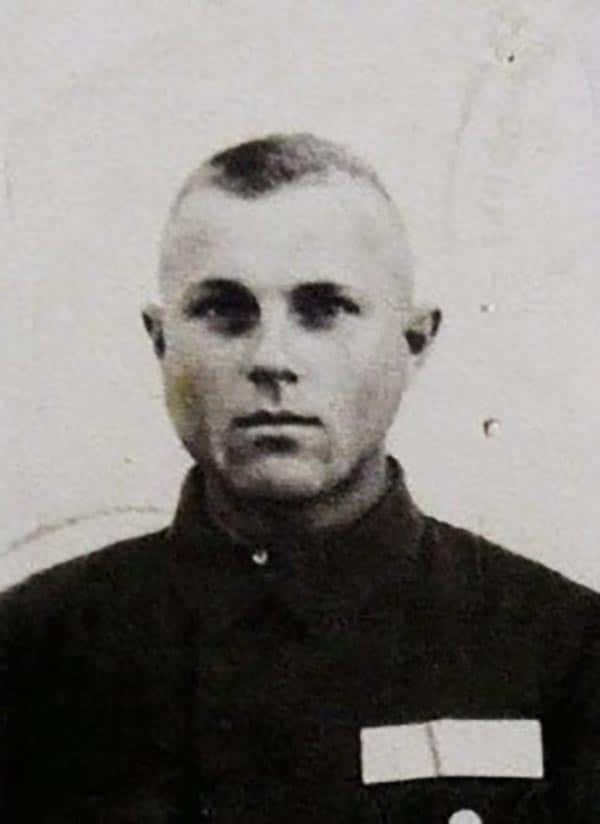

Like many other immigrants in his town of Seven Hills, Ohio, Demjanjuk worked at the Ford auto plant. Attended Ukrainian church with his family. Was generally considered a good neighbor and a stand-up guy. So it came as a shock to his friends and family when the U.S. government filed proceedings against him in 1977 to strip him of his American citizenship. Their grounds? John – formerly known as Ivan – had lied on his citizenship application. Now, that’s already a major no-no. You really shouldn’t lie to the United States government, it’s just generally not a good idea. Especially not about being in the SS. That’s right. The U.S. government alleged that mild-mannered John – the immigrant success story, the American everyman – had served as an SS guard in a number of Nazi camps during WWII. And the survivor testimony about his behavior there was bloodcurdling.

But before we get there, quick nerd corner: You’ve heard the term SS, or Schutzstaffel. The SS was originally established as Adolf Hitler’s personal bodyguard unit, and became an elite part of the Nazi Reich. But it would later become specifically charged with the implementation of the “Final Solution,” i.e. the murder of European Jews.

Okay, now back to Demjanjuk. See, something interesting happened. See, usually, when a denaturalized citizen gets deported, they get sent back to their country of origin. Makes sense, right? But not Demjanjuk. Because for the first time ever, the State of Israel made a special request of the US government. Send him to us. We’ve got some unfinished business. And the United States agreed. That’s how John Demjanjuk ended up on a plane to Israel on February 27, 1986.

By the way, if you caught the 9-year delay from the U.S. deciding to strip him of American citizenship to when he was actually extradited to Israel, sharp ear! Why the heck did it take so long? Well, after the US decided to extradite Demjanjuk to Israel, his defense team raised complicated legal challenges, not to mention the delicate political and diplomatic complexities that the US had to dance around.

Anyway, the 66-year-old spent the next year in solitary confinement at the Ayalon prison, waiting for his trial to begin. From the start, he and his family vigorously maintained his innocence. They spent months searching for an Israeli attorney to join his defense team. But no one wanted to touch the case. Except for one guy, Yoram Sheftel. I’m going to play you a couple of clips from “The Devil Next Door,” because Sheftel might just be the most outrageous character we’ve ever featured on the podcast, which is saying something. So I want to let him speak for himself:

“There is a Yiddish expression called auftzeluchesdicker. It’s a person that refuse to obey the general norms, to behave exactly as expected, a troublemaker.”

“And you enjoy being this?”

“Yes. Yes. I don’t have to put too much effort towards it. It comes out of me naturally.”

As you might imagine, this flavor of troublemaking – defending a Nazi accused of almost cartoonish sadism – didn’t earn Sheftel any admirers in Israel. Eli Gabay, one of Demjanjuk’s prosecutors, said of Sheftel: “He embodied, for me, a traitor.” Israeli reporter Noah Klieger, who covered the trial, agreed: “I can’t tell you what I think about Sheftel, because he’d sue me immediately. But I’m sorry that there are Jews like Sheftel.” And that’s why, when I told my friend Dani Ross to check out this documentary, he texted me: “This guy is the worst person on earth.” Dani was so disturbed, he followed up with, “That’s one of the most horrible things ever learnt about or seen…There is something very wrong with you, Noam.” Thanks, Dani. Now, Dani is wont to exaggerate, but I want to reiterate how wild that is! He wasn’t saying that the SS guard was the worst person on earth – he was saying that Sheftel, the lawyer defending him, was!

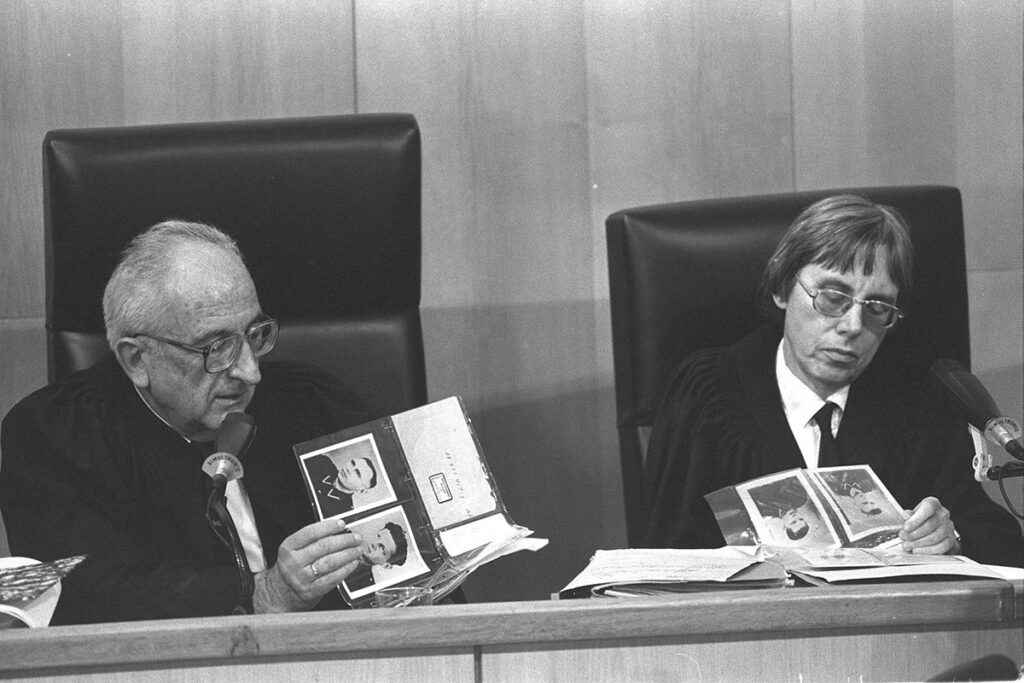

And it was bad enough that Sheftel was defending an SS guard. But the accusations against Demjanjuk were harrowing. The trial opened on February 16, 1987, and it’s hard to describe what a big deal it was. It was the first fully televised trial in Israel. Not only was everyone in Israel watching, everyone had an opinion. Each side presented a wildly different, and sometimes inconsistent, version of events. But the prosecution’s case shocked the nation, because its key witnesses had been victims, they claimed, of Demjanjuk’s brutality. And their stories were beyond imagination.

The prosecution’s case shocked the nation because its key witnesses had been victims, they claimed, of Demjanjuk’s brutality. And their stories were beyond imagination.

So, what do we know? Everyone, including Demjanjuk himself, agrees that he served in the Soviet army until he was captured by the Germans in 1942. Andddd, that’s where the stories begin to diverge. Because Demjanjuk claims that he spent the rest of the war as a POW, suffering along with all the other prisoners in a German concentration camp. But others who were there – fellow Soviets POWs, SS guards, and Jewish prisoners alike – tell a very different story. They contend that Demjanjuk was no mere POW. That he volunteered to join the SS, who were only too happy to accept a Soviet recruit.

By 1942, when Demjanjuk was taken prisoner, the Nazi regime had already begun implementing Operation Reinhard – a remarkably bloodless name for their plan to murder every single Jew in German-occupied Poland. It was for this purpose that they built the three death camps of Belzec, Treblinka II, and Sobibor.

Nerd corner alert: you may have heard of Sobibor, or at least the incredibly powerful Holocaust movie, “Escape From Sobibor.” But you may not remember that Sobibor was a particularly horrific death camp, in which more than 160,000 people were killed over only 2 years. That’s just under 250 people a day, which is honestly hard for me to wrap my mind around. At the end of the war, only around 50 people – TOTAL – survived Sobibor. And Sobibor, Belzer, and Treblinka II, well, it’s weird to think about the logistics in the face of this sort of death, but to run places like that, you need overseers. You need guards. You need people to power the machinery of death.

People like Demjanjuk. According to the prosecution, he learned how to be an SS guard at Trawniki, a concentration camp turned SS training ground. And then, depending on who’s telling the story, he was sent to work at Flossenburg. Or Sobibor. Or Majdanek. Or some combination.

According to survivors, Demjanjuk later ended up at Treblinka — a labor camp that expanded into an extermination center in 1942. If you want to be technical about it, Treblinka was a labor camp; Treblinka II was the death camp. Its only purpose was killing people — mostly but not exclusively Jews from Warsaw and the surrounding areas. But even a death camp needs forced labor, right? Someone to “welcome” new arrivals and confiscate their valuables. Someone to sort through these stolen goods and send them off to Germany. Someone to clean out the boxcars that brought thousands upon thousands of terrified Jews to the doors of hell, and prepare each train for the next transport. Someone to herd prisoners towards the “showers” and haul their bodies out to the crematoria once the gas did its job.

These jobs fell to sonderkommandos – Jews forced to burn the bodies of their friends and neighbors and loved ones. I don’t believe there’s a hierarchy of suffering. That one group of Holocaust victims had it “worse” than another. But I will say this: sonderkommandos experienced a unique and particular kind of horror. The horror of being forced to participate in the systemized genocide of their own people, before they too were murdered and replaced with new arrivals.

It was these sonderkommandos who testified to Demjanjuk’s legendary cruelty at Treblinka. Jewish prisoners knew their SS guards only by their first names, or their nicknames. They didn’t know the name Demjanjuk. They knew only that the guard with the harsh face and the cruel eyes was named Ivan. Their nickname for him was Ivan Grozny — Ivan the Terrible, after the brutal 16th-century Russian czar. Pinhas Epstein was only 17 years old when he was forced to become a sonderkommando, removing corpses from the gas chambers to the crematoria. This is his testimony:

“I saw a large man, and he was operating the engine. [Afterwards], they ordered [us] to open the doors and take out the corpses. This Ivan would come out of the engine room and beat us [terribly] with his pipe. Sometimes, he would carry a sword. And he would crush skulls, cut ears, and torture the prisoners. It was unbelievable. Your Honors, we took out corpses. It was horrific to see. People with crushed faces, people with knife wounds, pregnant women stabbed in the gut, people with eyes poked out. There are no words.”

I remind you: this was broadcast all over Israel. How could the public tear themselves away? And how could they not believe the survivors? How could they not hate Demjanjuk and everything he represented? Nearly one million Jews and an unknown number of others were murdered at Treblinka. Fewer than 70 Jews survived. Fewer than seventy.

Survivor after survivor pointed to Demjanjuk as Ivan the Terrible. And still, he proclaimed his innocence, even trying to shake one survivor’s hand. The survivor — a former sonderkommando at Treblinka named Eliahu Rosenberg — shouted “How dare you, murderer,” and most of the courtroom followed suit. Think about who was sitting there. People who had seen — and survived — the worst moment of Jewish history. They wanted justice for their murdered mothers and fathers, their siblings, their children, their neighbors and spouses and friends. They wanted justice for an entire vanished world. And all their anger, all their grief, all their horror and trauma and loss focused on the portly 60-something who sat impassively in the courtroom, listening to a simultaneous Ukrainian translation of the proceedings through a large pair of headphones. Of course he was a murderer, this placid monster, who showed not a whit of emotion as survivors detailed his atrocities

Demjanjuk’s defense team didn’t help his image. His American lawyer, Mark O’Connor, shared a deep and mutual loathing with the three judges presiding over the case. He’d even asked the judges to disqualify themselves — kind of an odd choice for a person trying to save his client from the death penalty. But perhaps worst of all, O’Connor had dared to ask Rosenberg why he, a sonderkommando who knew that new arrivals were being herded to their deaths, never helped or warned them. Rosenberg — and, I’d wager, the entire Israeli public — seemed shocked by the question, finally shouting, “Don’t ask me. Ask him. Ask him what he would have done to me if I had tried.”

It was a tasteless question. But it was also a sign of how far the Israeli public had come. You might remember from our Eichmann, Kastner, and German reparations episodes that early Israelis had a complicated relationship to the Holocaust. (And if you don’t remember those episodes, go back and listen — they’re linked for you in the show notes.)

For the first decade of Israel’s existence, too many Israelis viewed Holocaust survivors with disdain, maybe even cruelty at times. At best, no one wanted to know their stories. At worst, they were accused of horrifying things. How was it possible that out of six million, they survived? What did they do? Who did they collaborate with? Who did they sell out?

That was the context of the Kastner trial of 1954, when it was the presiding judge, Benjamin Halevy, who posed the unanswerable questions to survivors.

Back in ’54, it was almost as though Israel was putting survivors on trial. But 33 years later, at the Demjanjuk trial of 1987, the state seemed to concentrate all its pain and trauma on a single SS guard, a sadistic but ultimately minor player in the wider story of the Holocaust. In so many ways, the case symbolized an evolution in how Israelis thought about the Holocaust. They weren’t ashamed of their survivors. They were fiercely protective. They wanted the entire world to know that forty years on, the wound hadn’t healed. Might never heal.

The prosecution called survivor to survivor to the stand. Their testimony was raw and impassioned and powerful. But it was also, sometimes, inconsistent. Humans are unreliable narrators at the best of times. Remembering is an imperfect process. But the survivors on the stand weren’t recalling the best of times. They were elderly people reaching back over 40-something years to excavate the worst moments of their lives. Their memories may have been entirely accurate. Or they may have been twisted and curdled by trauma and pain.

And perhaps that’s why one survivor, when asked how he traveled from Poland to Florida, responded “by train.”

Perhaps that’s why Eliahu Rosenberg, who stared into Demjanjuk’s eyes and swore they were the cruel flat eyes of Ivan the Terrible, had once sworn that Ivan had been killed during a 1943 prisoner uprising. Sheftel, smelling blood in the water, seized on these inconsistencies and ran, and the Israeli public hated him for it. They called him a kapo. A collaborator. A sympathizer. And Sheftel’s attitude did nothing to help his case or his client’s. He repeatedly referred to the trial as a “show,” and to this day, he mocks the witnesses called to the stand. “Some of the witnesses were liars. Some of the witnesses were seniles. And some of the witnesses were seniles and liars.”

Yikes.

But the survivors weren’t the only ones who offered inconsistent testimony. Because each time Demjanjuk took the stand, his story seemed to change. He was in a POW camp the whole time. No, he was in Sobibor. No, he meant he was working on a farm at Sobibor, as a prisoner of war. No, he had once had an SS tattoo marking his blood type, did the court want to see before he got it removed?

Sheftel plotzed as his client incriminated himself repeatedly, and to this day, he still refers to Demjanjuk as an ignorant peasant. The prosecution, on the other hand, was having a field day. And so was the public. It was one thing for an aging survivor to misremember a detail. But a Nazi’s ever-changing stories were clearly proof of guilt.

The judges handed down their decision on April 25, 1988.

The verdict: guilty.

The sentence: death.

Like Eichmann, Demjanjuk was a symbol of evil. And though his death couldn’t undo a single thing, it could, perhaps, nudge the balance of the universe ever so slightly toward justice. Across Israel, survivors cheered and cried. Even one of the judges teared up. Demjanjuk, seeming to show emotion for the first time, crossed himself repeatedly, looking shell-shocked.

But that’s not the end of the story.

It takes a long time to put someone to death. Demjanjuk was sentenced in April of 1988, then sent back to solitary, where he could hear workers constructing the gallows from which he’d hang. Meanwhile, his family and defense team prepared to appeal. You see, Demjanjuk was still awaiting his fate in the winter of 1991, when the Soviet Union dissolved. And with its collapse came a stream of previously undiscovered documents. Statements from SS guards that the Soviet Union had tried and sentenced. Many mentioned a particularly cruel guard named Ivan. But his last name wasn’t Demjanjuk. It was Marchenko. And each description of him varied wildly. Was he tall? Short? Brown eyes? Gray? Blue?

Was John Demjanjuk Ivan Marchenko?

It was this question that anchored Demjanjuk’s appeal. The lack of concrete and consistent evidence. The unreliability of witnesses. No one doubted that Demjanjuk had been an SS guard, or even that he had done bad things. But was he this particular SS guard? Was he being put on trial for being a terrible person, or for being Ivan the Terrible? The five Israeli Supreme Court judges who investigated Demjanjuk’s appeal were unanimous. Demjanjuk was an SS guard. And he was terrible. He may have even been the terrible SS guard that haunted Treblinka survivors so many years later. But they just didn’t know for sure. And so, in July of 1993 — more than five years after Demjanjuk’s original sentence — the Israeli Supreme Court handed down a 405-page decision overturning his prior conviction.

This is nuts!!

There was enough reasonable doubt about his identity that they simply could not convict him. And so, after years in solitary confinement, on the Israeli equivalent of death row, Demjanjuk was a free man.

The survivors who had testified against him were crushed. Can you imagine??

Somehow, justice had slipped through their fingers. If Demjanjuk wasn’t Ivan the Terrible, as they had said, then what did that say about their memories? Their experiences? A denial of the pain caused is often more painful than the pain itself. After hearing the judges’ decision, survivor Yosef Cherney told reporters, “I am in shock, great shock. The justices made a mistake. They have done an injustice to millions… They tell me I am not authentic! I wonder if it was worthwhile at all to survive the camps. The 6 million buried in Europe will ask me, what did you do for us, Yosef Cherney, and I will say to them, I did my best.”

Because ultimately, the judges and the public had two very different directives. In the words of Mordechai Kramnitzer, then-head of the Hebrew University Law School:

“We don’t make a decision about the historic truth. All we do is make a decision about the legal truth. This is a legal truth and not more.”

Survivors — and the wider public — cared about the historic truth. And the Israeli courts could have easily fallen into that same trap, convicting Demjanjuk on the basis of, well, being a Nazi. And maybe that’s what they would have done if the trial had taken place earlier, in 1950 instead of 1993.

But the Israel of 1993 didn’t need to convict and punish Demjanjuk for being a Nazi. The entire world had heard the survivor testimony. The entire world knew about the atrocities of the Holocaust. More importantly, Israelis heard. Israelis knew. Israelis were acutely conscious of the legacy of trauma. And I have to say, for me, this is really important, and really hard. Whether we like it or not, the Holocaust and the Jewish state are inextricably linked. I do not subscribe to the notion that Israel exists because of the Holocaust, it always makes me cringe when I hear it. BUT, I very much subscribe to the idea that if there were already an Israel, there would have been no Holocaust. And that is why these trials take on a national consciousness. So, the very fact that the Israeli justice system let him go free because of an element of doubt says a heck of a lot about how the Israeli legal system works.

I do not subscribe to the notion that Israel exists because of the Holocaust. But I very much subscribe to the idea that if there were already an Israel, there would have been no Holocaust.

So back to Demjanjuk — sending one elderly Nazi to the gallows might have felt beside the point. Could a single, elderly Nazi’s death ever even the scale? How to measure one brutal but ultimately bit player against six million deaths? It wouldn’t be enough. Nothing could ever be enough. Israeli journalist and historian Tom Segev told the press in 1993: “It’s a great day for the system… Yet at the same time, a man who has been declared a war criminal gets to go free, and that makes everyone feel uneasy.”

And I gotta tell you, I’m uneasy with the Demjanjuk verdict too. A big part of me thinks, who cares if he was Ivan the Terrible or just a terrible dude named Ivan? HIS BEHAVIOR WAS TERRIBLE. Evil. One less Nazi in the world can only be a good thing. But the other, more rational part reminds me that emotion and historical memory and even human morality aren’t the purview of the legal system. That it’s a good thing that the Israeli Supreme Court overturned the conviction. That as much as it hurt, the court simply was not willing to sentence a man to death on sketchy evidence. So after nearly a decade in an Israeli prison, Demjanjuk was free.

But that’s also not the end of the story. Demjanjuk returned to the United States, where he fought for five years to restore his citizenship. He won his case in 1998, only to be stripped of his citizenship a second time in 2002, on grounds that he had been an SS guard, at Trawniki and Sobibor and Majdanek and Flossenburg, if not at Treblinka. Once more he was deported from the United States — this time to Germany, where he’d stand trial as an 89-year-old for crimes committed in his 20s.

Demjanjuk had spent most of his life fighting. And now, he was fighting the German government, protesting that he was too old and sick to stand trial. And, you know, just Google pictures of Demjanjuk on trial in Germany. He looked…sad. Pathetic. He was almost 90, couldn’t walk or even stand. He entered court in either wheelchairs or a hospital bed. And according to his family and lawyers, he was also living with severe mental ailments. But the trial carried on. 16 months later, Demjanjuk was convicted and sentenced for the last time. He’d worked as an SS guard. He’d been an accessory to thousands of deaths – specifically, 28,060 murders. For his crimes, he’d serve five years in prison.

Demjanjuk died in 2012, a month shy of his 92nd birthday, without ever having served his sentence. But his case marked an important precedent in German legal history. For the first time, German prosecutors argued that SS guards — you know, the little guys, the guys who were just following orders — were just as culpable in the deaths of their prisoners as the big guns, the planners, the Hitlers and the Himmlers and the Eichmanns.

But by then, the world had mostly moved on. After all, it had been almost 65 years since the Holocaust. No one outside of his family or his legal team thought much about Demjanjuk or Ivan the Terrible. There’s an old Hebrew curse: yemach shemo. May his name be erased. And for a few years, until the Netflix documentary dug up the past, Demjanjuk’s name was, if not erased, then at least mostly forgotten.

So that’s the insane story of the Demjanjuk trial, and here are your five fast facts.

- In 1977, the United States stripped a seemingly ordinary guy named John Demjanjuk of his citizenship, alleging that he’d been an SS guard at the Treblinka extermination camp.

- At Israel’s request, the US extradited Demjanjuk to stand trial in Israel for crimes against humanity. The star of his defense team was a flashy and controversial attorney named Yoram Sheftel, who took on the case out of sheer contrariness, much to the disgust of his fellow citizens.

- Every moment of the Demjanjuk trial was recorded and broadcast to a rapt Israeli public. The eyewitness testimony was particularly harrowing, and though Demjanjuk steadfastly maintained his innocence, all three judges – as well as most Israelis – found him guilty, sentencing him to death in 1988.

- But the sentence was never carried out. When the USSR dissolved in 1991, a treasure trove of documents from the Soviet archives introduced enough doubt about Demjanjuk’s identity to overturn his conviction in Israel. After nearly a decade in an Israeli prison, he returned to the US and campaigned for his citizenship to be restored.

- But Demjanjuk had only a couple of years to enjoy his restored American citizenship before it was stripped for a second and final time, again on grounds that he’d served as an SS guard. In 2009, Demjanjuk was deported to Germany, where he was indicted and convicted of being an accessory to over 28,000 murders. He died in 2012 while appealing his case.

Those are your five fast facts, but here’s one enduring lesson as I see it.

Grappling with genocide is a process. And not always a graceful one. Just a couple years after the war, the United States was wooing former Nazis into NASA and the CIA. As difficult as it is to stomach, while these guys were really bad dudes, they were also useful in the fight against the USSR. And really, didn’t that serve the greater good? Even Israel recruited former Nazis in the fight against Egypt. (Links to all of this in the show notes.) Moral dilemmas are one thing. Survival is another.

And the struggle was even harder on a personal level. It took more than a decade for Israelis to begin letting go of some of the shame and disgust they felt toward Holocaust survivors. For thirteen years, Israelis refused to listen to survivors. But all that changed with the Eichmann trial of 1961. At last, survivors were allowed to tell their stories. At last, Israelis could really listen to those stories without judgment or anger, marveling at their fellow citizens’ resilience and their strength. The entire trial was a sort of collective catharsis — the moment that Israelis opened up to the possibility that the Jewish people were survivors, not merely victims. And all of this happened on the world stage. Finally, the entire world began to understand a fraction of what the Jewish people had suffered. And the entire world saw as the man who implemented the Final Solution was tried, convicted, and sentenced to death by the people he’d tried to annihilate.

There was no doubt about who Eichmann was or what he had done. But there was some doubt about Demjanjuk. And so Israel did something painful and difficult. The Supreme Court let him go, understanding, perhaps, that human judgment is no match for — well, whatever is beyond us. That killing this old man might not serve the cause of justice. What would serve the cause of justice? I don’t know the answer to that, and I don’t think it’s my place to decide. That’s up to the people who were there. But there are fewer and fewer of them every day. Soon, there won’t be any survivors left. But it’s not just the survivors who are leaving us. It’s also the men and women on the other side. The ones who carried out the orders. Who herded prisoners into gas chambers with bayonets and manned the engines that released the poison gas. Did they take with them all hope of justice? Of forgiveness? Who is left to face justice, or to dole it out? Who is left to forgive?

I don’t know the answer to that.

But I know this. We weren’t there. And we can never, ever stand in judgment of someone who was. But we can honor their legacy. Like the survivor Yosef Cherney, we can carry the legacy of “the six million buried in Europe” who will ask us “what did you do for us?” And like Yosef Cherney, we can say to them only, “I did my best.”

We do our best by remembering. We do our best by telling their stories. By staring their murderers in the face. By recounting their crimes.. By knowing the names of the places they were killed. Flossenburg and Treblinka and Sobibor and Majdanek, Belzec and Chelmno and Auschwitz and Dachau. And by remembering the stories of fierce resistance.

Like the resistance of Emmy Cortissos, whose son, Rudolf, testified against Demjanjuk during his 2009 trial in Germany. The Nazis had picked Emmy up in a routine sweep and herded her on a train to Germany, where, they promised, she’d be given work. Before the train pulled out of the station, taking Emmy to her death, she tossed a letter out the window, hoping someone in her family would find it. She told her husband and children: “I promise you I will be tough and I will definitely survive. Hope to see you again soon. Bye bye. Many kisses.”

Emmy was not able to fulfill her promise. But her son, Rudolf – who was 70 years old in 2009 – did his best to fulfill his promise to her. Our promise to the Jews who came before us, who were murdered simply for being Jews.

Remember. Each life was an entire universe. We owe it to them to tell their stories.

So, those two sides of me I mentioned at the beginning? I am still grappling with it. Even as I grapple, I feel it is my obligation to tell these stories no matter what. To understand the Jewish psyche. To understand Israel. To understand the Jewish people.