Schwab: Welcome to Jewish History Unpacked where we’ll do exactly what it sounds like, unpack awesome stories in Jewish history.

Yael: I’m Yael Steiner and my childhood dream was to stay in school forever.

Schwab: And I’m Jonathan Schwab and I am in school forever. So Yael, what do you have for us today?

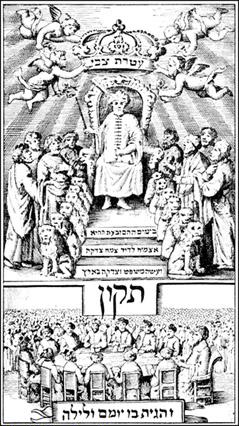

Yael: Well, I have my favorite kind of story today, which is about a very good looking, very charismatic young man. You may have heard of him. His name is Shabbetai Tzvi.

Schwab: Heard of him, yeah.

Yael: And he was a leader of a very large and very interesting Messianic group in the 1600s. One of the most successful, if not the most successful, false Messiahs in Jewish history.

Schwab: And that’s a high bar, false Messiah. Being successful at that is not easy.

Yael: What do you know about Shabbetai Tzvi?

Schwab: I know basically what you said. He was a false Messiah. I don’t think I offhand would’ve remembered that it was in the 1600s. The other thing that I know is that, as his life went on, his ideas and behavior went more and more off the rails. I don’t remember all the exact details of that, but it just got further and further from what was generally considered acceptable.

Yael: Social media would have loved him. He would have been trending for quite a while.

Schwab: People love a train wreck. Or I guess watching something go off the rails is something people love.

Yael: Yes. We all love rubbernecking. He was born in 1626 in Smyrna or İzmir, which is now part of Turkey, and I think was part of Turkey then or the Ottoman Empire. And from a young age, he was really notable in his community. He was very bright. He was a student who was exceeding the knowledge of his teachers by the age of 12. He was, as I mentioned earlier, very handsome, never hurts. And he also had a beautiful singing voice.

By the age of 18, he had been ordained as a hakham, which is a similar title to a rabbi or really the equivalent of a rabbi in some of the Sephardi Jewish communities, though I do believe he was not Sephardi.

Around that time, probably between the ages of 18 and his early 20s, began to exhibit some odd behavior. There is a consensus now among historians that Shabbetai Tzvi feel likely had some sort of bipolar mental condition. I personally get very uncomfortable saying that someone has a mental illness without being a psychiatrist or having met them. He certainly experienced fits of mania, followed often by bouts of depression, so he does fit in broad strokes, and you would know a little more being married to a psychiatrist and all.

Schwab: My wife is a psychiatrist so I can diagnose historical figures.

Yael: Exactly. So there does seem to be a consensus that he was bipolar. And when he started having these fits of mania, he began telling his community that was already bewitched by him because of his charisma and his good looks, and his smarts, that he was having these illuminations.

And the reason that these illuminations, which I’ll get into exactly what they were in a moment, were so compelling, is that this was a time when the ideas of Kabbalah were really starting to stream into Europe from Safed in Israel, these ideas that were espoused by the Arizal who was Rabbi Isaac Luria, who I believe was the forebear of Kabbalah.

And because we’re now in an age where there is a printing press and travel is getting slightly easier, and literacy has grown, literacy among women, particularly in the Jewish community, had grown, and I think that was a big driver in ultimately people following Shabbetai Tzvi because it might be hard to get a family out of the house if the woman is not on board.So the notions of Kabbala are coming up from Safed.

And we are also in the aftermath of the Chmielnicki pogroms in Eastern Europe, which were very devastating to the Jewish community and created a large refugee population that begins streaming into different areas of Europe. So you have people who are displaced, who are seeking something both geographically, seeking a home, permanence. And I think that seeking this ideological permanence or something to grasp onto is probably very compelling to them. So you have these two factors creating a perfect storm for a charismatic leader to gain some followers.

Schwab: It’s so interesting because you mentioned the printing press and increased literacy in the spread of ideas. And I usually think of those things as tied to Enlightenment and philosophy, and an increase in very rational scientific thought. And Kabbala is a lot more about an organized mysticism, but it sounds like being able to spread more printed materials allowed for what I wouldn’t usually characterize as a rational philosophy.

Yael: Correct. It’s not only the scientists who are able to utilize the printing press. It’s very much the difference between going to the supermarket and picking up the National Inquirer versus picking up The Economist. Those are two magazines that are spreading two very different stories of the world.

Schwab: And that’s such a great point. The easier it is to hear people’s thoughts or for them to express them, doesn’t always mean we’re getting the most rational and scientific perspectives on things.

Yael: Correct. And this is something that has been in the news a lot lately, but has been true since the beginning of the concept of freedom of speech, is with freedom of speech comes the freedom to express positions that could be wrong, or could be dangerous, or could be hurtful to people.

So even back in the 1600s, this was an issue, and even back in the 1600s, different type of information was spreading around the world.

So clearly the printing press had a big influence. So all sorts of ideas are spreading at this time, and newly literate people are eager to follow up on things that they’re reading that are interesting. All of a sudden, you’re getting news from places that isn’t just your individual village, and there’s a big world out there and in a big world, there are big ideas.

Schwab: We haven’t even gone to what his ideas were, but how far were his ideas spreading?

Yael: His ideas had spread definitely to the Holy Land. Ultimately the first person to declare him as a messiah was a man named Nathan of Gaza who was, as his name indicates, of Gaza. Before we get there, let’s talk a little bit about what these ideas were that he had during his periods of illumination, which many now say were fits of mania.

Schwab: And Shabbetai Tzvi, is that a pseudonym or that’s his name that he was born with?

Yael: That is his name. It is his first and middle name. I don’t know if he had a surname. I’ve never seen one. The only reason I know that Tzvi is his middle name is because in some of the literature, his last wife, and the reason I say his last wife is because he had at least three human wives, and he also…

Schwab: Sounds like there’s a really good story there.

Yael: He married a Torah scroll, actually under a chuppah, had an officiated service in which he pledged himself in marriage to a Torah scroll, so at least three human wives and a Torah wife.

But his last wife, Sarah, is referred to in some of the literature as Sarah Tzvi. And a very, very knowledgeable historian of Shabbetai Tzvi points out that her name wasn’t Sarah Tzvi because Tzvi was indeed Shabbetai’s middle name. Back to the illuminations. The illuminations basically were notions that he had very much influenced by Kabbalah that the age of the Messiah is near. And what we can do to bring about the Messiah is bring these shattered pieces of the universe, which is a notion that comes from Kabbalah, and put them back together by doing Tikkunim, which are fixes, repairs of the world.

And in Kabbalah, in traditional… It’s weird to call it traditional Kabbalah, but in traditional KabbalahSchwab: Not the modern kind.

Yael: Yeah, not the Madonna version.

Schwab: That I was going to say, not the Madonna version of Kabbala.

Yael: Exactly. But in the 15th Century Kabbala, these Tikkunim the way that you did these repairs was through good works and traditional mitzvot.

Schwab: That sounds good.

Yael: Shabbetai Tzvi was antinomian, which is a new word that I just learned, which is he threw aside the traditional rules of Judaism, but he wasn’t an anarchist. He didn’t believe in no rules. He had just turned the rules, on their heads. He announced that certain tragic days in Jewish history should now be days of feast and celebration, notably Tisha B’Av which is the saddest day on the Jewish calendar, memorializing the destruction of the temple. He also claimed to have been born on Tisha B’Av which maybe he was, maybe he wasn’t. But how good of a story is it if you’re going to be a false Messiah, that you were born on Tisha B’Av?

Schwab: If you want to be the Messiah, you’ve got to have the right origin story.

Yael: Exactly.

Schwab: But you’re saying maybe that was the way he told his origin story.

Yael: I’m saying nobody submitted a signed birth certificate.

Schwab: We don’t have the receipts to prove.

Yael: We don’t have the short form. We don’t have the long form. We just don’t know. Okay. So Shabbetai Tzvi threw a lot of these societal mores on their heads…

Schwab: And that’s the way to repair the world, he’s saying.

Yael: Correct. And most compellingly probably for a lot of people was he particularly did not like sexual norms. He encouraged a lot of sexual exploration. He did not believe in monogamous sexual relationships. He did not believe in private sexual relationships. And obviously there’s a rabbit hole here that we can go down, but basically it’s good publicity when you’re somebody who says, “Hey, you can do what you want in that realm.”

Schwab: And not just because it’s interesting for you, but this is actually, you’re doing good for the world. I can see how he would get a big following from that.

Yael: Exactly. It’s not a hard sell.

Schwab: And there was antisemitism and pogroms in the mix, so it sounds like people were looking for something positive or feeling a sense of empowerment, or that they were making a difference.

Yael: Absolutely. That’s a great point. People were looking for something that made them happy, made them feel good, and was something where they felt like they belonged. And especially if you had grown up in a traditional home where maybe a lot of these notions were forbidden or not talked about, this is something that’s very exciting and compelling.

Schwab: And I know that that’s also, when horrible things happen and when there’s tragedies and we try to make sense of them, it’s very appealing to think, well this is you know, the birth pangs of the messiah.

Yael: And that was the notion that was being spread from Rabbi Isaac Luria in Safed, and that was something that Shabbetai Tzvi grasped onto. So he starts to gain followers and he starts to become popular because he has some pretty cool ideas about how we can live our lives.

Schwab: And he had this hype man, Nathan.

Yael: Yes. So in the 1660s he crosses paths with this individual Nathan of Gaza, and Nathan of Gaza takes Shabbetai Tzvi from the amateur level to the professional level. He’s the hype man that he needs. And Nathan proclaims Shabbetai Tzvi to be the Messiah, and Shabbetai Tzvi is like “Cool, I’ll be the Messiah.”

Schwab: If you’re going to call me the Messiah, I’m not going to say no.

Yael: Exactly. I don’t know too much about Nathan, and based on what I’ve read and conversations that I’ve had with people who are significantly more knowledgeable than me, there is a little bit of a whole in the historical research on Nathan, and if there are any budding Jewish historians out there, I think we would all really benefit from some in-depth research on Nathan of Gaza, how he crossed paths with Shabbetai Tzvi, and what it was that compelled him to make this declaration.

I do believe that Nathan of Gaza desired to follow Shabbetai Tzvi in his later travels, but for reasons that I’m not sure of, and I don’t know if anyone is sure of, he never ultimately left Gaza.

So Nathan makes this proclamation and he shoots Shabbetai Tzvi into the stratosphere, but then he disappears into the background, at least for this part of the story.

Shabbetai Tzvi returning from the Holy Land up into the area where he had come from, sees what’s going on in the Holy Land and in Jerusalem, that it is being ruled by the Ottomans and goes to the Sultan in Constantinople to declare that the Sultan should make him the person in charge of Jerusalem.

At this point in time, Shabbetai Tzvi has a lot of followers and he has followers who have sold all of their belongings and followed him to Constantinople.

Schwab: Very dedicated followers. They’re not just reading his books. They’re wearing the Shabbetai Tzvi merch, going on tour with him.

Yael: They’re Shabbetai Tzvi roadies, and they have sold all their belongings. They have moved from places all over Europe to follow him to Constantinople.

And I think this is, as I said earlier, literacy had spread to both men and women. And I think that’s important because the women were also very taken by his message. And that I think also probably was helpful in getting these families to migrate behind him.

The problem is… Small problem.

Schwab: I feel like maybe there are a few problems, but I’m curious which one is going to come up.

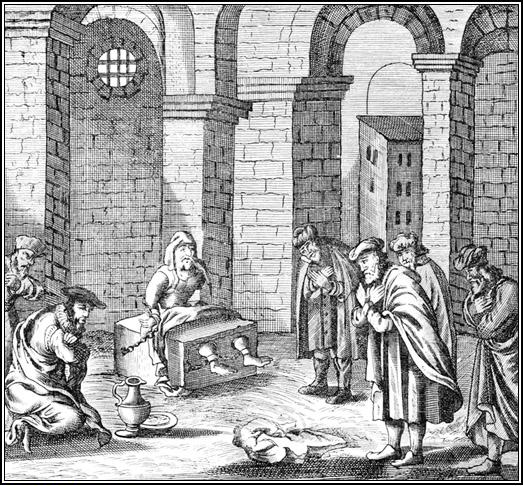

Yael: The Sultan does not want to give Shabbetai Tzvi control of Jerusalem. He’s not into that. He is not taken by this gentleman and he basically says, “I’m going to throw you in prison, (which he does,) “But I’ll let you out if you convert to Islam.”

Schwab: Oh boy. I feel like I know what happens next.

Yael: And I’m not exactly sure how long it takes, but it’s not that long, and Shabbetai Tzvi and his wife Sarah, who is the last wife that I told you about earlier, they convert to Islam and they’re released from prison.

This is super disappointing to a lot of people

Schwab: I imagine.

Yael: Yes. So this is where the canonization or idealization of Shabbetai Tzvi ends for a lot of people. And he himself as a figure doesn’t really come back from this. He’s not revived in the people’s eyes. But his notions, ideas of these tikkunim don’t die out that quickly, probably because a lot of them are fun and a lot of them are interesting.

In addition to some of the things he changed that we talked about earlier, one proclamation he made was that all of the three large Jewish festivals, Passover, Sukkoth, and Shavuot should be celebrated within one week rather than at three different times throughout the year. And as I know both of us are now coming off a holiday season in which…

Schwab: It does sound very appealing in terms of managing work schedule.

Yael: Exactly. Cooking, getting the family together.

Schwab: You just have one week where you do it all. You have the rest of the year to recover.

Yael: I could see why that would be compelling as well. So his message outlasts him. Sabbateans, as his followers are called, continue to exist in the Jewish community for at least 100 years I think, and they aren’t really cast out of the Jewish community. The mainstream Jewish community does not consider them to be others. It’s the way in today’s Jewish community, there are people with a lot of different beliefs and some people who are considered to be on the fringes, but we still have room for them in the big tent, and so his ideas continue.

Part of the reason why I think his ideas continue is that a lot of his followers were descended from conversos, who are the Spanish and Portuguese Jews who were forced to convert at the time of the Inquisition, and maybe are finding their way back to Judaism right now, so they’re looking to reconnect to something. Shabbetai Tzvi is offering them something, and I think now that they’ve found it, it’s a little hard to give it up.

Schwab: That’s interesting that also that people who have that history of conversion in that case to Christianity, now their leader converts to a different religion.

Yael: And it’s interesting, there’s actually a group of his followers who think that Shabbetai Tzvi’s conversion to Islam is a part of this process of the birth pangs of the Messiah. Rather than casting him off as a failed leader, they say, ‘Oh, this is just part of the process,” and they become these quasi Muslim-Jews, a community called the Donmeh, which actually still exists today really, obviously its in small numbers. They were people who were so compelled by Shabbetai Tzvi and believed in his arc as the Messiah so fully that they didn’t want to see his conversion as a failure. They saw it maybe as oppression of him, and in solidarity, they continued to follow a lot of his ideas and maybe adopted some principles of Islam.

Schwab: It’s so interesting because we’ve had many leaders and ideas and there’s the people and there’s the ideas, and can there be really good ideas, even if the people don’t turn out to exemplify all of those? Then it sounds like there are people who see them as, “Well, we’re so taken in by this person that everything must be part of it. We can’t set aside the person but keep the ideas. We are going to take the whole package.”

Yael: Even though there are so many tidbits and fun facts about him that I think are interesting, I just want to throw in one more thing before we talk about what you just mentioned and how this really resonates with us today, is his relationship with women. In addition to casting off a lot of the rules, the Halachot of Jewish life, one of the things that Shabbetai Tzvi did was really include women in the public sphere and in ritual Jewish life. He allowed women to be called up to the Torah for Aliyot.

Schwab: Wow. Ahead of his time.

Yael: Yeah, very. And that’s something that clearly resonates with a lot of people today. It’s certainly something that’s right that’s in the conversation.

Schwab: A big question of how do we make sure that people are included and feel included in our ritual observances.

Yael: But at the same time, he had a very weird relationship with women. His first two marriages ended in divorce and were never consummated. Subsequent to that, that’s when he really came forward with his pronouncements on sexual activity as being a way to reach God, as being part of the Tikkunim So you can make of that what you will. Maybe another question for the psychiatrists in our lives.

Schwab: So he has these two failed marriages to women and then he marries a Torah at some point.

Yael: Yes. He marries a Torah and then he marries Sarah.

Schwab: And that marriage worked out.

Yael: I think the marriage to the Torah worked out. I’m honestly not sure how things progressed there. And then he married Sarah, who had a very salacious reputation, came from a refugee family in the wake of Chmielnicki Pogroms. She was known to be a woman of the world, as they might call her. And some people say that he even married her for that reason. The prophet Hosea was known as having taken a wife with a checkered past, I think is the euphemism that’s used when they talk about her, and maybe by marrying Sarah, he was bolstering his claim to be the Messiah.

Schwab: Interesting. Here I’m doing this prophetic thing.

Yael: I apologize. That’s not true because he married Sarah a year or two before he met Nathan, so it was maybe bolstering his claim to have this connection to God, not necessarily to be the Messiah, because the Messiah claim came after.

Schwab: I just keep hearing a lot of doubting. Maybe it wasn’t just him, maybe he was the real Messiah. And I don’t know, what if it was all real?

Yael: Listen, I do not claim to have all the answers. It’s certainly something to think about. And I think you make a good point in that charismatic leaders, do we know that our current charismatic leaders are not in the lineage of the birth pangs of the Messiah. And obviously some of our charismatic leaders disappoint us.

Unfortunately, we all know of leaders, particularly in the Jewish community who have long esteemed careers and are found out later on in life to have been doing things that are illegal, dangerous, inappropriate.

And that’s a challenge for all of us. I know that in my own life there have been teachers and rabbis who I’ve found to be wonderful educators, charismatic leaders, and I’ve learned later on have used that charisma for the negative, and it is hard to grapple with.

Schwab: Yeah. Unfortunately, a lot of examples of that more than we can even get into now, and without even going into specifics, I think it is really hard to think about and how does this color then the ideas that they might have stated or good that they might have done in the world? Can we take a good idea or an appealing idea, or some good that someone did in the world if they also did some bad?

Yael: Right. I mean, we talk about this, even, let’s take it out of the Jewish community. Thomas Jefferson was a slave owner and a very, very important figure in the founding of this country, and wrote the Declaration of Independence. And if you study the history of the writing of the Declaration of Independence, did actually want to include some language against slavery while simultaneously owning slaves. People are complicated. Very complicated.

Schwab: Yeah. And how do we balance that if we’re not doing that with also respecting and valuing people who were hurt? And it sounds like there probably were people who were hurt by Shabbetai Tzvi, not in the same way, or who were… It sounds like there were followers, but there were also probably people who felt very betrayed by…

Yael: Listen, a lot of these people who followed him to Constantinople had given up all of their worldly belongings. They had really believed that they were going to be under the wing of a man who was going to be in charge of Jerusalem and that they would go to Jerusalem., And the age of Messiah was not even upon us, it was on us, and they were going to build the temple.

So people’s lives, and then they were horribly disappointed and in a new place with no money and no belongings, probably didn’t speak the language. So there were people whose lives were really horribly impacted.

Schwab: It’s such an appealing idea because it allows us to make sense of things that are painful in the world. We see horrible things happening. You can say, “Well, that’s reflective of the fact that the world is broken,” and it is within our ability to take steps to repair it.

Yael: Yeah. We want to feel like redemption is near, and everything that’s painful that’s happening is because we’re so close and we can get over that line if we take it upon ourselves to do these Tikkunim.

The world moves so fast nowadays, who knows if this will even be relevant by the time anybody’s listening to us have this discussion. But if Shabbetai Tzvi had had a shoe deal with Adidas, do you think you would’ve kept it?

We’re dealing right now with a lot of charismatic figures in the news. Kyrie Irving, a basketball player for the Nets, was suspended last night for amplifying the message of a highly antisemitic film on Amazon.

And if you look at social media, if you look at the news, there are people who are highly, highly devoted to these individuals and believe that any punishment that comes to them or any consequences to their actions is the result of a cabal of Jews trying to ruin the world or take over the world.

Schwab: Because it’s so hard for us. Not personally very into Kanye West, but I can see how if you hold somebody on a high pedestal and think that they’re speaking a lot of truths and values, that when they seem to fall from that, it’s very easy to say, “well, it’s not their fault. It’s some force working against them in some way.”

Yael: Or it’s just part of their greatness.

Schwab: Or this is part of it. That’s interesting also because there’s a real connection here with this question of mental illness and how much of this is that versus well, this is part of the brands and part of the plan all along and these things are somehow deeply true.

Yael: Or part of what makes this person unique and what makes this person such an outlier. Even with our political leaders, I think we were talking about this a little bit earlier. I think whatever party or ideology you identify with, I think our political system has gotten so outlandish that you could be someone who follows a candidate or believes in a candidate, and if you had been asked hypothetically three years ago or five years ago, would you support a person who does X, Y, and Z, you could have said, “Oh, I would never support a person who does that.”

But now, because we’ve become so enamored with personalities of our political leaders, because that personality espouses the idea, that same person who said five years ago, “I would never support X, Y, or Z,” is saying, “Well, I support it now because it’s part of the movement. It’s part of what we need to redeem our country.”

Schwab: There’s a shift in the normalization, like Shabbetai Tzvi starts out talking about, “Let’s repair the world and let’s question some of the things that we’ve always done and let’s think about different ways of doing things, and let’s celebrate the holidays all at once, and turn fast days into feast days.” Okay, I’m with you so far.

Yael: Have a little fun! And nothing that he originally espoused was dangerous.

Schwab: And then all of a sudden he’s converting to Islam, but not all of a sudden. It really is a progression that’s taking place over time. And people are getting swept up in that.

Yael: Convincing people to give up all their earthly belongings and follow him.

Schwab: Well, any good cult leader knows that’s not the first thing you do. You got to draw people in.

Yael: Yes. You have to draw them in. Yes. I learned that from a lot of after school specials. I don’t know if any of you watch Boy Meets World, but there’s one episode where Cory has to go rescue Shawn from a cult because Shawn lost his mother, his father’s on the road all the time, and he needs to grasp something, and there’s this really charismatic cult leader. I can’t believe I’m talking so seriously about Boy Meets World, but there’s this really charismatic cult leader who gives him something, who gives him something emotional to belong in a place where he feels like he belongs. And then Cory has to rescue him.

Schwab: And that sense of belonging and meaning in a world that’s confusing and difficult, it is really important.

Yael: Yeah. And sometimes that sense of belonging or the need to belong is so strong that we don’t realize what it is that we’re giving up in order to be a part of it. We don’t see it until it’s already slipped away. We don’t see ourselves migrating away from friends or family, or giving up values that were very important to us because the feeling of belonging is a really good feeling.

Schwab: Yeah. Well this is great because I always knew a little bit about Shabbetai Tzvi and thought I was going to learn a lot more about his colorful history, which I did, but…

Yael: We have not even scratched the surface.

Schwab: Yeah. It sounds like there’s so much more.

Yael: His last wife, Sarah, who I mentioned before, he divorced her and said that the reason he was divorcing her was because she was a leper, and he needed to rid himself of leprosy. And then he remarried her immediately. This guy just… he would have been Twitter darling.

Schwab: Oh my gosh. People would’ve loved it. There’s no bad Shabbetai Tzvi stories. Every story about him is amazing.

Yael: Correct.

Schwab: But in so many ways, the story, or at least the way I’m thinking about it, is he’s a really colorful, interesting figure, but it’s the people and the followers, and his ideas and how they all grappled with it that’s the really interesting part.

Yael: Yeah. If Shabbetai Tzvi never meets Nathan of Gaza, who knows? And again, this is a pitch to all you budding historians out there. Somebody write a book about Nathan of Gaza.

Schwab: Yeah, I thought you were going to say this is a pitch to everybody out there of there are 1,000,001 false Messiahs, but the way to really make it happen is everybody needs a Nathan of Gaza.

Yael: Yeah. Or there are 1,000,001 false Messiahs, but there’s only one me. Now I have to get my ideas in my head. No, I’m just kidding.

And I guess what do we take away from this? Be healthily skeptical of our leaders, not trying to pull anyone away from a leader that they feel really strongly about and who inspires them. Those are really important people to have in our lives. And walking this fine line, it’s a challenge for me. I’m sure it’s a challenge for many of you.

Schwab: Yeah. And we can always balance that. We can hear some of what someone is saying, but being wary of following them down every road that they go.

Yael: There doesn’t have to be a purity test. People can have good ideas and also have bad ideas. Both things can be true.

Schwab: But if people do want to sell all of their earthly possessions and sponsor future episodes of the podcast, we do accept that, right?

Yael: Correct. And we won’t take you to Constantinople. We’ll let you stay exactly where you are.

ENDING:

Thank you for listening to Jewish History Unpacked a production of Unpacked, a division of Open Door media. If you like this show, subscribe on your podcast app of choice and give us five stars and write us a review on Apple Podcasts. Check out Jewish Unpacked for everything Unpacked related, and subscribe to our other podcasts. And of course, check out our TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter. Just look for @JewishUnpacked, and most importantly, be in touch with Yael and Schwab. Write to us at Jewishhistoryunpacked@jewishunpacked.com.

This episode was hosted by Jonathan Schwab and Yael Steiner. Our education lead is Dr. Henry Abramson. Audio was edited by Rob Pera and we’re produced by me, Rivky Stern. Thanks for listening. See you next week.