This podcast might be called “Unpacking Israeli History,” but today, we’re going global.

Cause today’s episode is about world Jewry — and in particular, how the global Jewish community mobilized to bring Soviet Jews from out behind the Iron Curtain.

And that means that today’s story is about identity. What it means to be Jewish in a country that persecutes you for it, and what it means to be Jewish in a country that’s free. It’s a story about heroes from different parts of the world. But most importantly, it’s a story of a people who had a second chance to make a difference, and spoiler alert, boy did they deliver….

What’s that about? It’ll all come together. I promise.

If you’ve been listening to this podcast for a while, you already know that I love a “fun fact” — one of those implausible historical tidbits that makes you an absolute boss at bar trivia and a total weirdo in a normal conversation.

Like, for example, the fact that Abraham Lincoln, samurais, and fax machines overlapped for like a 20-year-period, so technically, President Lincoln could have sent a fax to a samurai. (Is this actually true? I’m not 100% sure. But I want to believe that it is. No one correct me!) But perhaps more relevant to this particular podcast is the fact that way back in 1949, the head of the Israeli Workers’ Party, Mapam, reportedly said this: “The Soviet Union is the fortress of world socialism, it is our second homeland, the socialist one.” A second homeland?? As one of my favorite 90s show’s main characters, Martin, always said… Damn, Gina!

Turns out, the USSR and Israel? Kind of a weird relationship. What other country has gone from supporting the creation of the Jewish state to hating the Jewish state, to upending Israeli society and demographics, all over a few decades?

I can name countries that hated Israel and now love it. (Hi, UAE!). Countries that loved Israel, and then hated it. (Hey, Uganda!) And countries that sent floods of refugees into the only Jewish state, dramatically reshaping its culture. (Shalom shalom to the entire Arab and Muslim world!)

But the USSR is the only country that fulfills all three of those criteria. Its relationship to Israel is utterly unique. Sui generis, some might say. And because the story of the USSR and Israel is full of twists and turns, we’ve got to go back to the beginning, which in this case is the Communist Revolution of 1917, so it’s not exactly the beginning, but still earlier, which seemed, at first, to be Good News for the Jews.

In the words of Boruch Gorin, chairman of Moscow’s Jewish Museum, quote, “There was great and undeniable enthusiasm among basically all the elements that made up Russian Jewry.” I mean, of course a heavily persecuted minority group fully embraced the promise of equal rights. For a few years, Jews enjoyed an almost unheard-of level of tolerance and integration in Russia.

The optimism continued through WWII. After all, it was Soviet soldiers – Jewish and otherwise – who liberated Auschwitz. Plus, Joseph Stalin actually supported the creation of the State of Israel, hoping the socialist Jewish state could act as a Soviet ally in a fractious region. The USSR was the second country, after the US, to officially recognize Israel, and Moscow even indirectly supplied Israeli forces with weapons.

So of course Mapam’s leader spoke of the USSR as a second Jewish homeland. Russia loved Israel. Israel’s workers loved Russia. What a boon for the tiny Jewish state to have a big bad empire in its corner.

But nobody puts the USSR in a corner. At least, no one who is also courting the Americans.

See, like any country trying not to get annihilated by its much larger neighbors, Israel was hedging its bets. So as the Cold War heated up, the Jewish state tried its best to stay neutral in the boxing match between the US and the USSR. But that neutrality didn’t last long. Because in June of 1950, North Korea invaded the Republic of Korea (aka South Korea). The USSR backed the North. The US supported the south. And for a number of philosophical and pragmatic reasons, Israel lent its voice to the chorus of countries condemning North Korea, essentially saying, hey, we’re with the US on this one.

Well, the USSR really didn’t like that. The cozier Israel got with America, the angrier Stalin became. And the Israelis didn’t help matters when they gently suggested to Stalin that perhaps the USSR’s Jews belonged in Israel. But Stalin insisted that, like all Soviets, Jews were happy and productive in Russia! They didn’t need another form of nationalism. And they certainly didn’t need to feel special or different from the rest of the masses. According to Stalin, they were Soviets first, and Jews second, or third, or tenth – if at all.

Some Soviet Jews agreed. Jewish journalist Ilya Ehrenburg wrote in 1948: “The State of Israel has nothing to do with the Jews of the Soviet Union, where there is no Jewish problem, and therefore no need for Israel.”

But the Israeli government generally assumed that, all things being equal, most Soviet Jews would probably choose to leave the USSR in favor of a Jewish state. And the best proof of this was the 1948 visit of Israel’s very first ambassador to the USSR: one Golda Myerson, aka future Prime Minister Golda Meir.

Though Stalin welcomed Golda, Soviet authorities warned local Jews to stay away from the Israelis. But the Soviet Jewish community came out to Golda Meir’s Rosh Hashanah address at the Moscow Choral Synagogue in droves.

As she later wrote, quote: “Instead of the 2,000-odd Jews who usually came to synagogue on the holidays, a crowd of close to 50,000 was waiting for us. For a minute I couldn’t grasp what had happened — or even who they were. And then it dawned on me. They had come — those good, brave Jews — in order to demonstrate their sense of kinship and to celebrate the establishment of the State of Israel.”

And at the end of that first visit, as she was bundled into a taxi, she simply said in Yiddish, and I’m sorry if I butcher this a little bit, and I will, ‘A dank eich vos ihr seit geblieben Yidden.’ (Thank you for having remained Jews.)”

Stalin, however, was less than appreciative. He seeded the crowd with MGB agents — that’s the precursor to the KGB — who took note of names. Within a matter of months, many of the Jews who had come to greet Golda Meir were in exile or prison. And Stalin began to use the state press to attack any Jews who dared to dream of a life in Israel.

By the early 50s, Stalin’s anti-Jewish purges were in full swing. He executed 13 members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee — the Jewish group that had churned out anti-Nazi, pro-Soviet propaganda during WWII, raising millions of dollars for the Soviet war effort in the early 40s. A year later, he accused nine doctors — six of whom were Jewish — of plotting against Soviet leadership. Under brutal torture, they confessed, of course.

Stalin died just a few days before their quote unquote “trial” — and I’m putting that in heavy air quotes, because you know this trial was a sham.

But the damage was done. The press had already attacked these doctors as being, quote, “mercenary agents of a foreign power.” It was a classic blood libel. In fact, Stalin planned to use the trial to further mass protests, arrests, and deportations of Soviet Jews. He simply died before he could make it all happen.

Stalin’s successors weren’t quite as fanatical about wiping out Soviet Jewish life. But they weren’t exactly good to the Jews. By the early 60s, Jewish life in the USSR was intolerable. Anti-Jewish quotas restricted Jews’ access to education and jobs. The threat of the secret police lurked behind every corner. Jewish identity and pride were shoved deep underground.

The few synagogues that weren’t shut down were crawling with KGB agents. Journalist and author Yossi Klein Halevi writes that, quote, “most worshippers were too terrified even to speak with Jewish tourists from the West; those few who did would only allow themselves to brush up against a visitor and whisper urgently, “They don’t let us live,” or, “Why are American Jews silent?” before slipping back into the Soviet oblivion.”

In 1965, an Israeli newspaper sent Elie Weisel — yes, that Elie Weisel — to investigate the situation of Soviet Jews. His subsequent book, “The Jews of Silence,” described the nearly complete severing of Soviet Jews from their identity. It was a risk to discuss Judaism. To celebrate Jewish holidays. To speak Hebrew or Yiddish. To be proud to be Jewish. And yet, Weisel described a fierce – and dangerous – defiance. He wrote that, “Despite everything, they wish to remain Jews.”

So let me ask you. What makes a Jew? Is it a Jewish school? A kosher butcher? A synagogue? A mikvah? A community scribe? A Hebrew teacher? A mohel to perform brit milah and a rabbi to perform weddings? A seder? A latke on the first night of Chanukah?

The American-Russian musician Regina Spektor, who spent the first nine years of her life in the USSR, reflected in an NPR interview that “there wasn’t really any kind of like religious — you couldn’t go to synagogue, you couldn’t do stuff like that — but we did have little, like, relics of religion. Like we, my grandmother, my mom’s mom would always make sure that we, we knew when Passover was and she would somehow get – through a connection of a connection, we would have matzo. And, and so she would make, you know chicken soup with matzo balls. But then we would have bread alongside that because we didn’t know that you are not supposed to eat bread.”

And I want to pause on that for a second. I want to really think about the fact that so many Soviet Jews were simultaneously disconnected from their heritage… and committed to celebrating however they could. Like Golda Meir had noted back during her 1948 visit, they wished to remain Jews despite the odds stacked against them.

Meir wasn’t the only person who was deeply touched by this commitment. A world away, American Jews, or Jewish Americans, whatever you prefer, were watching. And what they did next changed the course of world history.

You know the Passover story, right? Moses tells Pharaoh to let his people go; Pharaoh refuses; miracles ensue; and eventually the Jewish people end up on the shores of the Sea of Reeds with the Egyptians at their backs, wondering if they’re going to make it to the Promised Land after all.

According to the midrash, God doesn’t split the sea immediately. In an incredible show of faith, a man named Nachshon the son of Aminadav wades into the water. And even as the waves surge around his knees and his chest, people follow him, inspired. Only then does God split the sea.

If the global movement to save Soviet Jewry had a Nachshon, it would probably be a name many people have not heard of…He’s not a big rabbinic leader, never won a Pulitzer, or a Noble prize…His name is Jacob Birnbaum. As Yossi Klein Halevi put it, quote, “In the early spring of 1964, an imposing man in his late thirties, tall, with a…beard, a British accent, and a Russian-style fur hat, appeared on the campus of Yeshiva University… and began knocking on dormitory doors. For weeks, he went from room to room, soliciting support for a cause of which few people had yet heard: Saving the Jews of the Soviet Union.”

He called their plight a “spiritual genocide.” And he insisted that American Jews had the power, resources, and responsibility, to end the second Jewish genocide of the 20th century.

Remember folks, we’re less than two decades removed from the Holocaust. One third of world Jewry is gone. And over a million Soviet Jews are trapped behind the Iron Curtain. Birnbaum was determined to convince global Jewry to do everything in their power to help.

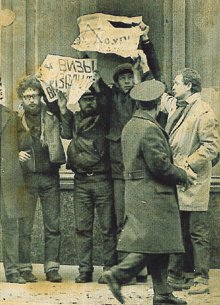

Birnbaum wasn’t the only mover and shaker of this movement. But his organization, the Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry, or SSSJ, inspired others. And soon, that first protest in 1964 swelled to a massive movement, attracting senators, celebrities, and a Who’s Who of future Jewish leaders.

Like Rabbi Haskell Lookstein, once called “the second most influential Rabbi in America,” whose sermons are brilliant, I’ve heard them, they’re amazing, and they’ve been covered in the New York Times, whose synagogue Kehillat Jeshurun and school Ramaz are household names in the Jewish education world. And fun fact, my wife Raizie went to Ramaz for high school.

Like Rabbi Avi Weiss, founder of the Open Orthodox movement and the first to ordain female Orthodox rabbis.

Like Rabbi Meir Kahane, the controversial firebrand who founded the Jewish Defense League, which broke into Soviet diplomatic offices in the US to protest their anti-Jewish policies.

Like Zeesy Schnur, the executive director of the Greater New York Conference on Soviet Jewry.

And legions more besides, from every denomination, every institution. From Israel. From the US. And, of course, from the USSR. It would take an entire podcast to name them all. There were so many heroes of this movement. So many people who devoted everything to this cause. Global Jewry had never been so united. And I don’t think I’m just being nostalgic by saying that. Jews were standing up for one another. And they’d never been so proud to be Jewish.

Because right as the movement was gaining steam, the Six Day War changed everything. Over the course of a week in 1967, Israel fought off three armies, more than tripled its territory, and set the entire Jewish world on fire with a new sense of pride.

Including, in the Soviet Union. To quote, again, from Yossi Klein Halevi, “The war created widespread public identification with Israel. Young Moscow Jews greeted each other by covering one eye, simulating who? That’s right, Moshe Dayan’s eye patch. For the first time since the 1920s, when the Bolsheviks destroyed the Zionist movement in the Soviet Union, Zionist circles began operating openly in major Soviet cities.”

The USSR, which had backed Israel’s enemies, immediately broke off relations with the Jewish state. But the mighty empire just kept getting humiliated by those pesky Jews! In 1967, a Moscow University student named Yasha Kazakov made international headlines when his open letter to the Kremlin was smuggled out of the USSR and published in the Washington Post. He wrote: “I consider myself a citizen of the State of Israel. I demand to be freed from the humiliation of Soviet citizenship.”

Almost immediately, Kazakov was granted a visa to Israel. But the rest of his circle was not so lucky. Boris Kochubiyevsky (I hope I said that right), an engineer from Kyiv, was sentenced to three years in prison for writing to Soviet officials, quote: “I will do all I can to leave for Israel. And if you find it possible to sentence me for that, then all the same. If I live until my release, I will be prepared to go to the homeland of my ancestors, even if it means going on foot.” For this, he earned the dubious honor of becoming the first so-called Prisoner of Zion, a Jew who is imprisoned or deported for being an active Zionist. Sadly, he was far from the last.

Because as you might remember from our episode on UN Resolution 3379 — well, let me just play it for you: “the U.S.S.R really didn’t like being made to look foolish in front of its own satellite states. The Kremlin’s propaganda campaign against Jews was swift and vicious… The KGB chairman Yuri Andropov was explicit about the U.S.S.R’s aims: ‘We needed to instill a Nazi-style hatred for the Jews throughout the Islamic world, and to turn this weapon of the emotions into a terrorist bloodbath against Israel and its main supporter, the United States.’”

The propaganda was bad enough, but declaring Zionists to be “enemies of the state” made Zionist activism outright dangerous. Not that this swayed the fearless Soviet Jews from applying to emigrate to Israel from the USSR.

Some made it, representing the first, small Soviet Aliyah of the 70s. But most applications were refused, for a variety of trumped-up reasons. Stuff like “You can’t leave! You know state secrets!” (Listeners, I’m prepared to bet that not a single one of these applicants actually knew state secrets. But I digress.)

And the Jews whose applications to emigrate were denied were known as refuseniks, a fun name for a very un-fun status. Because, you see, once they applied to leave, the refuseniks became official enemies of the state. Their applications cost them their jobs, their homes, their privacy and their safety, as they became targets of the secret police. Inevitably, they were arrested and sentenced to prison or hard labor for years on end.

And still, Jewish refuseniks kept agitating. They studied Hebrew. They learned as much as they could about Jewish holidays and culture. They sought out other Jews. They wrote letters of protest to any media outlet they could. They passed around samizdat, contraband literature, which was sometimes copied by hand on notebook paper and passed from person to person. Examples of samizdat included the work of Vladimir Jabotinsky, as well as Leon Uris’ novel Exodus and the poetry of Chaim Nachman Bialik. (Side note: check out the links in the show notes for more on Jabotinsky and Bialik.)

As if passing around contraband literature wasn’t enough, one group of refuseniks decided to take matters into their own hands. If the government wouldn’t let them emigrate to Israel, they’d get there themselves.

How do you get from the USSR to Israel? Oh, easy. You just hijack a plane. And yes, each one of these stories is absolutely crazier than the next.

Now, this was not some kind of Entebbe situation. (Of course, link in the show notes to that episode.) These dissidents didn’t hurt anybody or take any prisoners. Instead they planned to buy every single seat on a small 12-seater plane and simply… fly it to Israel under the radar, disguised as relatives en route to a wedding.

They called their plan, and I love this name, Operation Wedding. And it would be easy peasy. No one would get hurt. Everyone would win. But the KGB was watching. Mere steps from the plane, the refuseniks were arrested on charges of “high treason,” and two of them were sentenced to death.

The one woman in the group — Sylvia Zalmonson — was sentenced to 10 years of hard labor in the gulag. And yet, she was undaunted, telling the court at her show trial, quote, “If you had not deprived us of our basic right to leave the Soviet Union, we would have simply purchased an airline ticket to Israel… Even now…, I believe the day will come that I will be in Israel. A faith that has lasted 2,000 years is giving me my hope. If I forget you, Jerusalem, may my right hand forget its cunning.” What. A. Boss.

I don’t know if the group really thought they’d get to Israel or if Operation Wedding was a highly risky publicity stunt. But either way, it worked. Within a matter of days, massive demonstrations in Europe and the US convinced Soviet officials to commute the death sentences to a “mere” 15 years in jail. And in the meantime, Sylvia became a symbol — one of many heroes of the dissident movement.

She was far from the only one. The movement was full of brave, mostly-young men and women who made international headlines with their chutzpah and grit. Like Ida Nudel, who had applied to leave for Israel in 1971. Her family got their exit visas. She didn’t. For the next seven years, she was one of the KGB’s favorite targets. They finally sentenced her to four years of exile in Siberia for the crime of hanging a banner over her balcony emblazoned with the words “KGB – GIVE ME MY EXIT VISA.” Seriously, these people are legends! (Side note: the KGB charged her with “malicious hooliganism,” which would be hilarious if it weren’t so terrible.). By the way, malicious hooliganism… kind of sounds like my high school years, not gonna lie.

Perhaps the best-known of all these prisoners of Zion is Natan Sharansky, who had applied for an exit visa in 1973 and was – surprise, surprise – refused. His future wife, Avital, was luckier. One day before she was due to leave for Israel, the couple married in a Jewish ceremony in a friend’s apartment – a marriage that the Soviet authorities, of course, did not recognize. Avital and Natan hoped to be reunited within the year. Instead, he was followed and harassed constantly by the KGB for three years, until he was finally arrested in March of 1977 on charges of treason and espionage.

He was convicted in 1978 and sentenced to 13 years in a Siberian forced labor camp. For much of the first 16 months of his sentence, he was held in solitary confinement. A Washington Post article from 1988 reflects, quote, “His health is still fragile, reflecting the ordeal of starvation diets that reduced his weight at one point to 77 pounds. He still suffers from… a weakening of the heart muscles, and recently was gripped… by the biting chest pains and sharp headaches that marked his long days in the punishment cell.”

Avital, who had made it to Israel, spent years campaigning on his behalf. She met with diplomats and heads of state – anyone who could help her husband. Of all the stories of courage and defiance, the Sharansky story sticks out. Not because their situation was particularly unique. But because for the nine years he languished in prison, Natan Sharansky resisted with every breath. The Washington Post reporter Glenn Frankel described Sharansky’s attitude as, quote, a “perilous existential ballet.” He “knew from the start that had he ever given in, decided to cooperate on even the smallest matter, he would have been lost forever.” Even after his release, when KGB officers demanded he walk in a straight line towards the airplane that would fly him to freedom, he refused, cutting a zigzag through the snow in defiance.

That same conviction animated every one of the Soviet refuseniks. It’s a conviction that has lasted. Because well after the fall of the USSR, post-Soviet Jews are still falling in love, all over again, with the Jewish identity that was robbed from them by so many years of oppressive policies.

When I was in college, I was lucky enough to travel to Belarus, with a program called YUSSR: which stands for Yeshiva and University Students for the Spiritual Revival of Soviet Jewry. I went twice: once in the summer, to lead a summer camp for teenagers. And once the next year, to help make Passover in a tiny village called Orsha.

My campers spoke no English. I spoke no Russian. We communicated primarily through a translator and really ridiculous hand gestures. But you didn’t need a translator or a dictionary to see how much these kids loved Judaism. They didn’t keep Shabbat or kosher. They didn’t have bar or bat mitzvahs. Some of them didn’t know what my tefillin were! And yet, when I put them on, the boys asked if they could try next. And they were so emotional when I showed them how to wind the straps around their arms. So excited. So full of love for this gesture that connected them to a wider Jewish community.

I get goosebumps thinking about that, reflecting on those memories.

Passover in Orsha was no less amazing. Unlike my campers, most of these villagers were older. They had lived most of their lives under the Soviet regime, and it wasn’t hard to see the parallels between the story in the Haggadah and the story playing out in real time, right in front of my eyes. Like my campers, most of these folks knew very little about Jewish observance. I’m not entirely sure they knew the details of the Passover story. For some reason, we didn’t even have maror, bitter herbs, on the seder plate.

What they lacked in bitter herbs, they more than made up with passion. They belted out old Zionist songs with such excitement, such overwhelming love, that it put us college kids to shame. Hevenu Shalom Aleichem. Yerushalayim Shel Zahav. HaTikvah. Listen, none of those are Passover songs, but that didn’t matter. These songs were how they’d kept the spark alive. This was the product of decades of defiance. Of generations of refusal to let the fire go out.

But if the Jews of the USSR were animated by defiance, their Western counterparts were powered by a different conviction.

Guilt. And also a deep and abiding love.

What did American Jews have to feel guilty about? They’re not the ones who brought the USSR to power. But in 1973, Rabbi Joseph Ber Soloveitchik made a radical suggestion. He said that on Yom Kippur, when Jews confess their sins, American Jews should consider adding a new one. ‘For the sin that we have sinned before You by seeing the suffering of our Jewish brethren who called to us and we did not listen.’ I’ll play his own words here:

“When the Holocaust took place, American Jews did not react properly. You could have saved many, many, many. Of course, you know, Roosevelt was no good, and the State Department was antisemitic, and Secretary Cordell Hall, I mean… But we did not exert any pressure. Not exert any pressure. Not at all!”

Does that make you as uncomfortable as it makes me? Because I believe fully that every iota of blame and shame for the Holocaust rests squarely on the Nazis and no one else. And yet, the American Jewish community nonetheless felt that they had not done enough. And it’s good they felt that way! Jacob Birnbaum wrote as much in his pamphlet announcing the SSSJ’s inaugural meeting: quote, “We, who condemn silence and inaction during the Nazi Holocaust, dare we keep silent now?” At marches, the SSSJ hoisted signs reading “This Time We Won’t Be Silent” and “I Am My Brother’s Keeper,” making their sense of collective responsibility clear.

And it worked. It was this activism that led, directly, to the passing of the Jackson-Vanick Amendment to the 1974 Trade Act. That’s a mouthful, but the amendment basically denied certain economic privileges to non-market economies that restricted the human right of free emigration. Which, again, is a convoluted way of saying that the US government hit the USSR where it hurt – in the pocketbook – because of their attitude towards Soviet Jews. The pressure was on.

By the mid-80s, the Soviet economy was in shambles, and the plight of Soviet Jews was the cause du jour. And the USSR’s new – and, it turned out, last – leader took notice. Some historians even point to the SSSJ as a defining factor in both the reforms of Mikhail Gorbachev, and in the eventual dissolution of the USSR. How’s that for making a change?

So as Gorbachev and Reagan prepared for a historic summit in Washington, D.C., the movement sprang into action, organizing a march on Washington that drew hundreds of thousands of Jews.

Including: Natan Scharansky. Yosef Mendelevitch, one of the refuseniks who had planned Operation Wedding. American Vice President George H.W. Bush. House Speaker James Wright. Senate Minority Leader Bob Dole. The Israeli ambassador to the USA. And, of course, ordinary Jews from all over the United States.

Between 250,000 and 300,000 of them, holding signs that read FREEDOM FOR SOVIET JEWS and ISRAEL IS OUR HOMELAND and LET MY PEOPLE GO.

They called it Freedom Sunday. It was the biggest mobilization of American Jews ever. And. It. Worked.

Gorbachev announced that any Jew who wished to emigrate to Israel would become welcome to do so. I don’t know what he expected, but I doubt it was what happened next: a flood of Jewish immigration, mostly to Israel. Between 1989 and the collapse of the USSR in 1991, half a million Jews streamed out of the USSR. Roughly 70% came to Israel. A decade later, over a million additional post-Soviet Jews had joined them.

And that changed everything, and I mean everything. Canadian-Israeli journalist Matti Friedman writes, quote: “Within a decade more than 1 million people immigrated to a country whose population in 1990, at the beginning of the wave, wasn’t even five times that number.”

But where the Israel of the 1950s had nearly buckled under the wave of immigrants, the Israel of the 1990s flourished. In many ways, and here is a secret most of us don’t realize, it was the Soviet aliyah that turned Israel into the tech powerhouse it is today. Soviet Jews brought with them highly advanced degrees in math and science, swelling the ranks at Israel’s most prestigious research university, the Technion. They brought with them high culture: classical music and opera; advanced chess players; a deep literary tradition. They brought with them unfamiliar customs like Novy God, Russian New Year, and new foods like adjaruli khachapuri, a Georgian dish that aside from being delicious is just fun to say. I LOVE KHACHAPURI!! Thank God for this movement!

The Soviet Jews also brought with them almost mythical stories of courage in the face of oppression. Prominent refuseniks like Natan Sharansky and Yuli Edelstein found new careers in politics, advocating for the integration of Soviet Jews into Israeli political life. In a surprise blow to the aspirations of Israel’s left-wing parties, Soviet Jews tended to vote with the right — not out of religious conviction but out of a deep skittishness towards anything that smacked of socialism or communism.

But immigrating is not easy, and neither is integration. Many Soviet Jews struggled at first — with the language and the heat and the constant violence, with what they perceived as “coarse” Israeli culture. And, with a sense of imposter syndrome. See, in Russia, though they knew little about Judaism, they had been Jews. Ironically, in Israel, where they were finally able to live as Jews, they were seen as Russians. Many were not even considered Jewish by the Orthodox rabbinate.

For some, it’s a bit of a slap in the face. That sense that you’ll always be Other-ed.

And it’s also the story of immigrants everywhere. The first generation of immigrants has it hard. But their kids? And their kids, and their kids?

They’re Israelis. And they’ve shaped the country’s character in complex and indelible ways. In fact, if you’re looking for a human story about the Russian aliyah, check out the second episode of another one of our podcasts from Unpacked, a narrative podcast, called Homeland: Ten Stories, One Israel. Of course, it’s linked for you in the show notes.

So that’s the story of the Russian aliyah, and here are your five fast facts.

- After the Communist revolution, Soviet Jews were not allowed to acknowledge their Jewishness, even while they were singled out for terrible treatment.

- Though the Soviets had at first backed Israel, they quickly turned against the Jewish state. Jews who tried to emigrate were denied.

- But the global Jewish population was watching, and they launched a campaign of such fervor and persistence that world governments began to pay attention. The Jewsh community had never been so unified.

- The pressure worked, and Gorbachev allowed Jews to emigrate. From 1989 until the USSR’s collapse in 1991, half a million Jews left the Soviet Union, and within the decade, over a million Jews from the former USSR had emigrated – mostly to Israel and the US.

- The Russian aliyah upended Israel’s demographics and culture, and both Soviet Jews and native Israelis struggled to mesh. But today, the kids and grandkids of these Soviet Jews are mostly integrated into Israeli society, a critical component of Israel’s success as a nation.

Those are your five fast facts, but here’s one enduring lesson as I see it.

Our head writer, Adi, told me a story that’s going to stick in my mind for a long time. She heard it from one of her high school teachers, who had spent his winter breaks traveling to the USSR with his students before its fall. It’s mind-blowing: high schoolers risking their lives to bring their brothers and sisters across the world just a tiny piece of their shared heritage.

To say nothing of the bravery of these Soviet Jews, who risked imprisonment, forced unemployment, hard labor, and maybe worse, just to accept these symbols of their heritage, brought from thousands of miles away. Anyway, in their suitcases, they carried artifacts of Jewish life, like prayer books, Shabbat candles, and kiddush cups. The students had been trained on what to say when questioned by Soviet authorities — and make no mistake, they were always questioned by Soviet authorities.

During one of these trips, the student delegation visited a family who had made a curious interior decorating choice. On their wall they’d hung an empty bag of Bamba or Bisli – some of my favorite Israeli snacks. Truth is, I prefer Bissli to Bamba, but let’s not get into it. Adi’s teacher asked them what the deal was. I don’t know what kind of answer he was expecting. But I know it wasn’t the one he got. Which was a loud and passionate cry of: “Ivrit! Ivrit!” Hebrew, Hebrew.

I can’t get that out of my mind. To us, these empty bags of Bissli or Bamba are basically trash. But to them, they were precious samizdat, contraband, a shiny “F You” to the Soviet policies that tried so hard to stamp out Jewish identity. Barred from celebrating their Judaism publicly, these Soviet Jews did the next best thing. They sought out whatever piece of their heritage they could find, and they cherished it.

Ivrit, ivrit.

I don’t mind telling you that hearing this story sparked a mini-existential crisis. Because here’s the thing. I’m lucky. It’s hard for me to remember a time I had to hide my Judaism, outside of that village in Belarus. Never felt compelled to tuck my kippah under a baseball cap. Never been denied the privilege of practicing Judaism however I want. And I’m so, so grateful for that. So grateful!

But that also means that I’ve never pinned an empty bag of Bamba up on my wall. Never risked death, or imprisonment, or hard labor, to remain Jewish. Never had to sacrifice much of anything.

And sometimes, a small, dark part of me wonders whether that’s a good thing. Whether, in the long run, we’re at our strongest when we’re under threat, whether the provocative and influential rabbi Arthur Hertzberg was right when he said about Jewish identity that the only thing more dangerous than antisemitism is NO antisemitism. Whether we would have survived if not for, you know, all the [bleep] that’s happened to us for the past two thousand years.

The Student Struggle to Save Soviet Jewry was the last time in living memory that the global Jewish community united, wholeheartedly, behind a single cause. Does that mean that we needed antisemitism to bring us together? What do we lose when things are too easy, too good?

What I’m really asking is, what keeps us Jewish? What’s gonna keep the next generation excited about their Judaism? What is our Student Struggle to Save Soviet Jewry? Is it antisemitism? Is it Kanye running his mouth, or attacks on Jews in the street, is it BDS?

I hate thinking this way. Hate it! It’s depressing. It’s reductive. And it does Judaism a disservice.

In late 2021, the Editor in Chief of the Jewish Journal, David Suissa, a good friend of mine, wrote an op-ed that I can’t get out of my mind, it’s great. He called it “The Best Way to Fight Anti-Semitism is With Happy Jews.” I’m going to read part of it to you, because it sums up exactly what I’ve been thinking about as I’ve researched this episode.

Quote: “Acknowledge that there’ll never be a cure for Jew-hatred and develop a vaccine that will inoculate Jews. This vaccine, it turns out, has been staring us in the face. It is Judaism itself.… The “pro-Judaism” movement needs to make a lot more noise. And I don’t mean just promoting “Jewish pride.” I mean disseminating more knowledge, more love for Judaism and its tradition. We don’t need more education about Jew-hatred; we need more education about Judaism.”

So what does that mean? When we’re building the next generation of happy Jews, how do we balance the grim stories of antisemitism and persecution with the joy of being Jewish? How do we acknowledge our resilience and resistance without making them the sole focus of the story?

I don’t have an exact answer. There’s no formula – one part happiness to two parts tears. And maybe every Jewish community has to strike a different balance, between learning about the challenges and celebrating the triumphs.

But I urge every single one of us to wrestle with this question.

If you’re Jewish, what keeps us Jewish?

If you’re Jewish, what does our Judaism mean?

And what cause will help guide this generation of Jews to stoke their fires and passions?