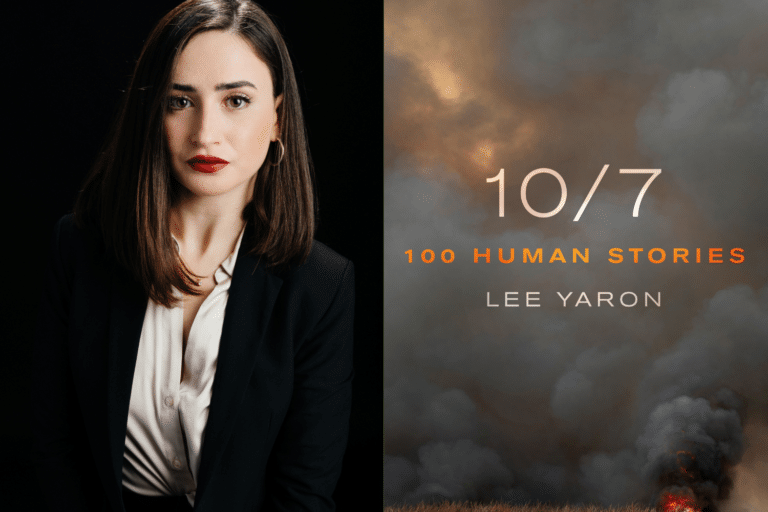

Israeli journalist Lee Yaron, who splits her time between New York and Tel Aviv was in the United States on Oct. 7. She immediately flew back to Israel, and spent the next few months interviewing hundreds of loved ones of those murdered by Hamas.

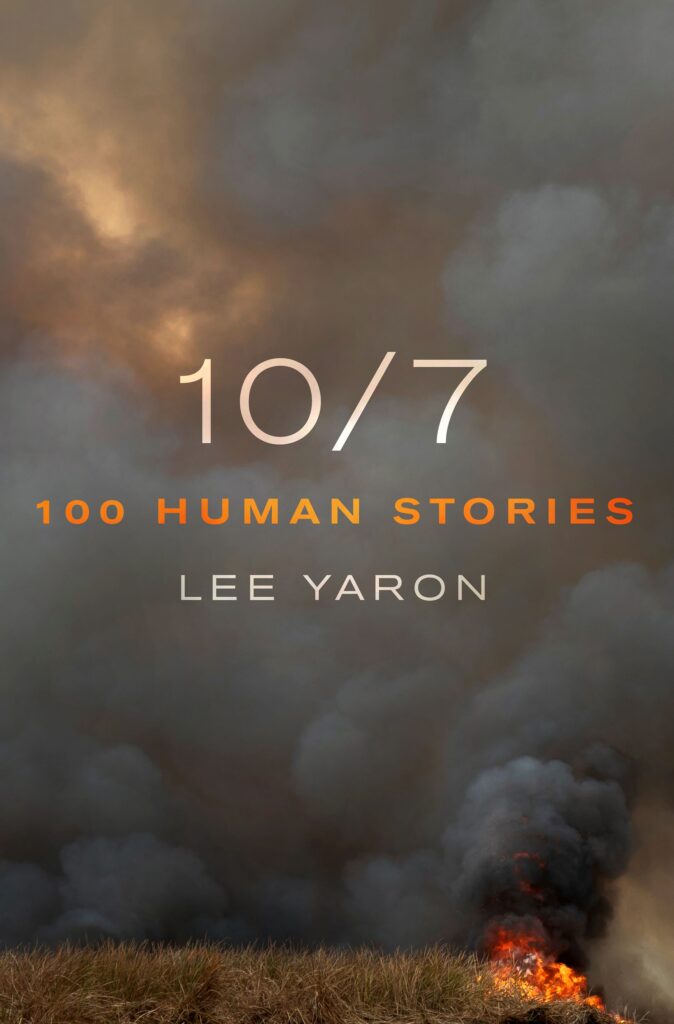

A reporter for Haaretz, one of Israel’s largest newspapers, Yaron was used to doing interviews. But for her new book “10/7: A Hundred Human Stories,” she spoke to hundreds of people who knew Hamas’ victims, but also those who had survived the violence. Lee Yaron spoke to Unpacked about her experience writing her new book about Oct. 7 and how, despite the horrific violence, she still hopes for peace.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

When you first heard about October 7, was your main reaction anger, fear, or a mixture of both?

I felt a lot of things, but I hoped my family in Ofakim would be okay. Forty-nine residents would be murdered. Members of my family hid in their homes. They were saved because they were lazy — they didn’t go into the shelter.

Have there been moments from your interviews that continue to stay with you months later?

There’s the story of Eitan, this kid that was an orphan from Ukraine and he left after Russia’s invasion to go to Israel, and then a Hamas rocket hit his home. I know Eitan felt this anger. He said “I don’t understand, once I felt Putin’s rockets. Now I feel Hamas’ rockets. What does everyone want from me? I just want a normal life. I don’t care about politics.”

Then you hear about the kibbutzim. So many of the victims were from the pro-peace community. They dedicated their lives to a two-state solution. They donated money to Gaza and took Palestinian kids to hospitals for treatment. When you speak with some of these families, you feel their anger and how they feel foolish that all of their lives they believed in making peace, and now their family is dead. For many, everything they believed in, they don’t believe in it anymore.

As a grandchild of Holocaust survivors, has working on this book made you reflect on history? Have you seen parallels?

What I’ve learned from the interviews is that Oct. 7 isn’t part of just Israeli history. Oct. 7 is part of Jewish history. When I was writing this book, I felt my work is the work of connecting this day to the wider context of the wound of generations feeling persecution from the pogroms. I feel it from my father’s side, Jews who survived the Holocaust. But I also felt it from my mother’s side that has family that came from Portugal on the eve of deportation.

Q: Prior to Oct. 7, did you think the security fence could not be breached?

When the fence broke on Oct. 7, it wasn’t just the physical barrier that crashed. It was a dream of generations of safety. I heard it time and again from the families of victims, from people who came from the Soviet Union, and immigrants from many other countries

Also, the idea of “Never Again” was so shaken. Shachar Zemach was a peace activist who did tours in Hebron and was active in trying to create a two-state solution, and on Oct. 7 he took his weapon and defended the clinic he worked at until he ran out of bullets. He put his hands up and he told the terrorists, “I’m not your enemy. Don’t kill me.” But they did. When you speak to Shachar’s father, Doron, he speaks about his mother, who was only 13 when she survived the Farhood pogrom in Baghdad in 1941. She saw Arab neighbors murdering Jewish neighbors, so she fled to Israel because she wanted a safe place for her sons and grandchildren.

In your book, you provide testimony of the sexual crimes against women. Yet some “journalists” go on podcasts and claim sexual violence did not take place on Oct. 7. Do you find it hurtful when they make these false claims, or do you ignore them and write them off?

I needed to see so many things I can’t share with people to write this book. I saw a lot of the pictures of sexual violence, especially from the Nova Festival and the kibbutzim. To be honest as a woman, these images are haunting me.

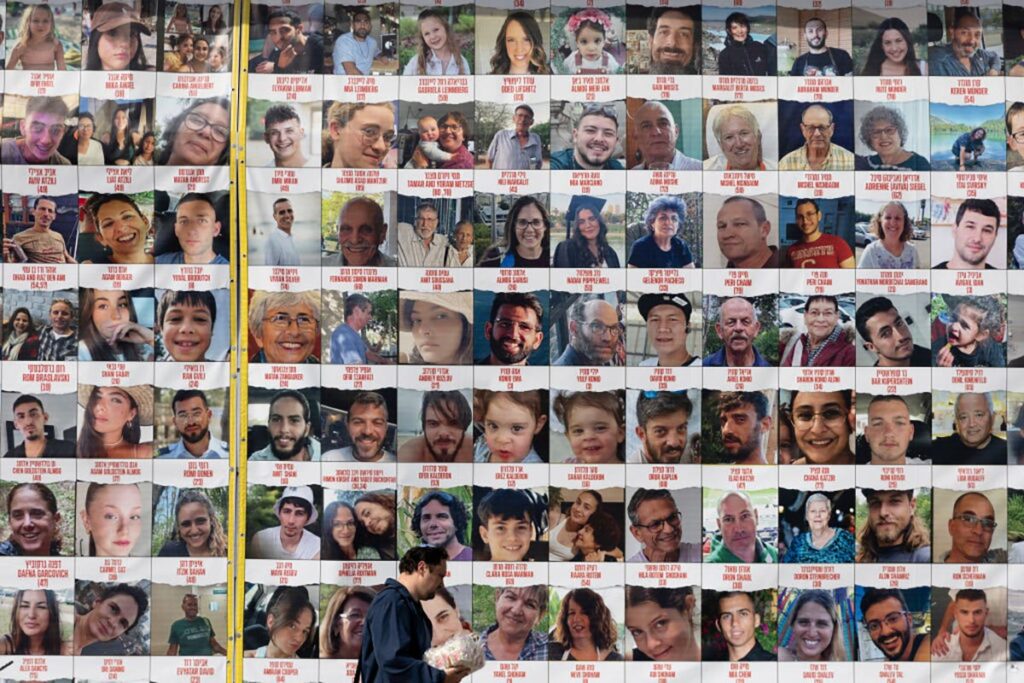

We live in a very difficult time where everything is so polarized and politicized. It’s painful and in many ways, the goal of my book is to go beyond a political agenda and numbers and statistics and reclaim the story of Oct. 7 from any political agenda, and talk about the real people that suffered from it. The point is to give readers a ground-level view of the people who suffered. I spoke with the victims’ parents who know how their children’s lives ended. When there are people who deny it, it does feel like a betrayal.

Some therapists who work with trauma patients require therapists of their own to cope. Did you worry that hearing the specifics of many horrific stories could traumatize you?

When I was writing this book, one of my closest friends Gal Eisenkot, 25, died in Gaza. He was a soldier on a mission to rescue hostages. The book is dedicated to Gal. He was a student who wanted to be a doctor. He was not a military man, but felt like so many others that he had to do what he could to protect Israel. From the moment Gal died, everything was mixed up. I tried to have some boundaries between my journalism and my personal life, but I found myself feeling like the people I was documenting. I felt like I was on the other side of grief. It was very painful and difficult.

In many ways, it was helpful for me to work on this book because it gave me a mission. I could be a voice for the people who were silenced. I could do something for their families. We can’t bring them back to life again, but we can bring them to life on paper. They should be remembered as who they were and not numbers or statistics.

Were you surprised that some ripped down hostage posters and supported Hamas at rallies?

I heard people chanting from the river to the sea at Columbia University and I heard settlers saying it in the West Bank. There is enough space between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea for all of us.

I understand protestors who want to achieve justice for Palestinians. Like many Israelis, I am horrified by those dying in Gaza. There are people who had nothing to do with the attack who died. I know we can’t achieve the perfect justice that protestors are imagining.

For me, Intifada is not a chant. My first memories are of the Intifada. When I was two months old, my mother was holding me and a bomb exploded near us. We have to understand we can’t change the past, but we can change the present and the future. I think people who want peace and safety for Palestinians have to understand that the fate of Israelis and Palestinians are intertwined. Like it or not, it’s reality. Seven million Jews have no other place to live. Two million Palestinians have no other place to live. And there are about 5 million Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank.

I hope we can work together and not against each other. I feel like we forget when we speak about Jewish victims, they are civilians. In other conflicts, people make a distinction between the government and the people but when it’s Israel, they don’t make that distinction. We need empathy. We need to build bridges between us and there is no better way than human stories to tell. It’s difficult to capture the humanity that was lost. I hope all of this energy can be used to unite people who want peace.

What is something people don’t speak about in relation to Oct. 7 and the IDF?

Something I’d like to point out is the gender aspect. There are no women in the war cabinet. There are barely any women in top leadership roles in the IDF. In Hamas, of course, there are no women leaders, and they live under Sharia law. Both sides of the conflict have only men making the decisions. There was a huge peace march of mothers on Oct. 4 who asked leaders to go to the negotiation table. One of the peace activists, Vivian Silver, was murdered in her home three days later.

Is Oct. 7 taught in Israel, Gaza, and the U.S. as far as you know?

People are living Oct. 7 every day. You don’t need to teach any kid in Israel or Gaza. This is their reality. I think it’s important for the future when the war is over and hopefully the hostages will be home, we will be able to think about that day. I think it’s more important in the US to know about it.

Reflecting on a possible deal, why was Israel in favor of the 2011 deal in which it released 1,027 prisoners for soldier and hostage Gilad Shalit?

I think it’s something deeper in our identity. We have mandatory military service. There is a kind of social contract that you don’t leave anyone behind. This contract allows parents to send their kids to the Army. I think with Gilad Shalit, people felt that if we broke this contract, we didn’t know what would be left of Israeli identity. It is such a core value. Even now, in making a deal. Sure, we’ll pay a price. But the price we will pay if we don’t make a deal will be heavier in terms of our identity as Israelis.

What is the most important thing you want people to take away from your book?

I want people to remember the victims. I want them to remember their stories. In reading the book some of the stories will affect them and maybe they will share it with others. I promised the families that their loved ones wouldn’t be forgotten.