On October 12, 1958, 50 sticks of dynamite exploded near the entrance of the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation in Atlanta, Georgia. The attack wasn’t simply a white supremacist assault on Jews, but an attack on the bond between the Jewish and Black communities in the South and their joint fight for Civil Rights.

While no one was injured, the attack had a dramatic impact. That bomb was, metaphorically, placed directly on a key fault line in the Jewish community, and the reverberations would be felt – across the American Jewish community.

How Civil Rights Became a Jewish Issue

Beginning after the Civil War and Black emancipation in the late 19th century, Black Americans still faced significant discrimination across America, and in the South they lived under a system of racial segregation that came to be known as the Jim Crow Laws. The US Supreme Court upheld these laws by ruling in Plessy v Ferguson that separate facilities were legal, as long as they were equal. While this meant that state and local governments could have separate but equal services and facilities for Blacks and whites, in reality, Black schools, buses, train cars, parks, and more were underfunded and inferior – if they existed at all.

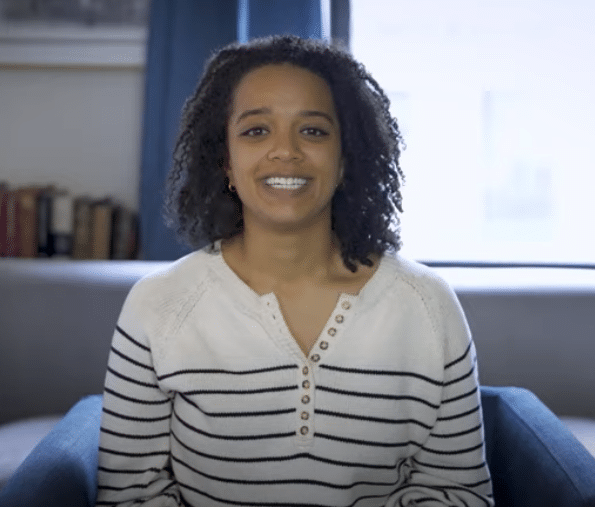

A personal perspective

We spoke to Kylie Unell, a Dean’s Doctoral Fellow at NYU concentrating in Jewish philosophy, about her family’s story. Kylie was named an “aspiring Jewish philosopher” by the New York Jewish Week’s 36 Under 36 and is a writer, podcaster, and the co-producer of the comedy show, Sweepstakes Comedy.

My hometown of Kansas City was not above such discrimination, especially in the school system. Yet, something really special about Kansas City is that it was home to incredible leaders in the fight against segregation: community organizers, ministers, and journalists.

One unexpected name on that list is Esther Swirk Brown. In 1948, this synagogue-attending homemaker was chatting with her Black housekeeper, Helen Swann, and found out about the inferior conditions of Helen’s children’s school. A brand new school had just been built for the White children, while Black children were learning in a one-room school built in 1888. Black parents had filed a lawsuit but the school board used the power of bureaucracy to avoid making changes.

Esther was no armchair activist and was well connected in the Black community. As in many cities across the country, housing codes in Kansas City discriminated against Blacks, Jews, and Catholics. This forced Jews and Blacks into the same neighborhoods and enabled the communities to recognize their shared struggle.

Esther helped Helen and other Black parents form an NAACP branch, file legal action, coordinate a boycott— and she raised money from the Jewish community for the cause. She continued her activism despite harassment, an FBI smear campaign, getting fired from her job – by her own father-in-law – and her husband being forced to resign from the Air Force Reserves on account of her activism.

After a 2-year legal battle, the Kansas Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Black plaintiffs in the case. Esther continued to raise funds for the legal crusade against school segregation in Kansas; the result of one of these cases being the US Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown (Oliver, not Esther) vs Board of Education, the landmark 1954 decision that prohibited segregation in all US public schools.

A year after the Brown v Board of Education decision, a 14-year-old Black boy named Emmett Till was lynched in Mississippi. While such a terrible event was not so unusual and hardly made headlines normally, a brutal posthumous photo of Till went the 1955 equivalent of viral causing an uproar. Then, later that year, a seamstress and active member of the NAACP, Rosa Parks, famously refused to give up her bus seat to a White passenger. These three events brought the civil rights movement to the forefront of the American consciousness and inspired many people to join the fight.

Over the previous half-century, Blacks and Jews had increasingly come together to fight discrimination, so by the 1950s, no one was surprised that Jewish activists made up a huge percentage of the non-Black people involved in the struggle. American Jews played a key role in the founding and funding of some of the most important civil rights organizations.

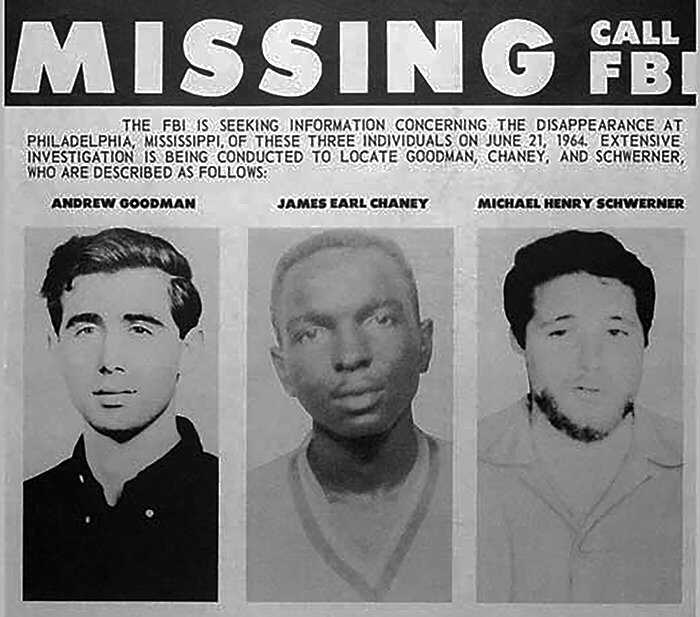

In 1964, a campaign known as the Mississippi Freedom Summer brought volunteers from across the country to help register Black voters in Mississippi. Black and White college students from the North—with a disproportionate number being Jews—were bussed down for the effort.

Early that summer, two Jewish activists, Michael Schwermer and Andrew Goodman, and one local activist, James Chaney, were arrested by a sheriff who was also a member of the Klu Klux Klan. Shortly thereafter, all three were driven out to a deserted area and murdered by a group of Klansmen. While the murder of Black men in the South rarely made national headlines, news of the murders of two white activists further publicized the unchecked, institutional violence of Southern segregationists.

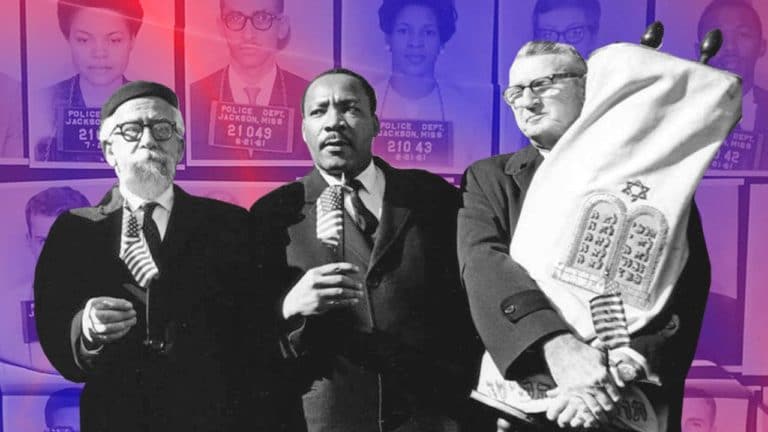

Just after Cheney, Goodman, and Schwermer disappeared, 17 rabbis were arrested alongside Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and others. Their crime? Sitting and praying at a “Whites Only” restaurant.

This was no isolated incident. King shared a long, fruitful relationship with many Jewish leaders. Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel walked arm-in-arm with Dr. King in his 1965 March on Selma, and Rabbi Joachim Printz warmed up the crowd for his good friend Dr. King to deliver his iconic “I Have A Dream” speech. AJC treasurer Stanley Levison was a close friend of Dr. King – he drafted some of his articles and speeches, prepared his tax returns, and raised money for organizations Dr. King supported.

Despite all of this cooperation, there were pockets of the Jewish community, especially in the South, that did not support and even opposed desegregation. The South was home to many Jews in the 1950s living on the periphery of a dominant white culture and a minority Black culture, both of which had their share of antisemitism. While a minority of Southern Jews supported segregation, others opposed it, and still others were simply afraid to rock the boat. A 1961 poll found that 40 percent of Southern Jews deemed the Supreme Court ruling to desegregate schools “unfortunate.” This was compared to 97% of Northern Jews who supported the decision.

The pressure Southern Jews faced is exemplified in the story of Atlanta’s Hebrew Benevolent Congregation. Their rabbi, Jacob Rothschild, was a rare, outspoken critic of segregation in the South, and he had his community’s support. After Rabbi Rothschild publicly supported the Brown v Board of Education ruling, white supremacists bombed the Temple, which was empty at the time, and then, made anonymous phone calls to community members threatening further violence.

Two years later, a bomb was thrown into a synagogue in Alabama. The bomb failed to detonate, but terrified congregants fled the building into an ambush – where the bomber shot at them, injuring two people.

All of this led to a split within the Jewish community over whether national Jewish organizations would show public support for desegregation. Some Southern Jews argued that Jewish organizations should focus on Jewish issues, and segregation was not a Jewish issue but a Black issue. The vast majority of Jewish supporters of desegregation argued that institutional discrimination was a threat to all minorities, including Jews and, therefore, the civil rights movement warranted public Jewish support. The split led some Southern Jews to withdraw from national Jewish organizations that had taken public stances against segregation.

Once again, Kansas City stands as a proud example of Jewish support for desegregation. Two years before his “I Have a Dream” speech, Dr. Martin Luther King spoke to 400 people at Congregation B’nai Jehudah, where Esther Swirk Brown was a proud member. Dr. King spoke that night about non-violent resistance, but he also had a message that was deeply relevant to a national Jewish community facing an unprecedented internal crisis. Dr. King counseled the congregants of B’nai Jehudah, “One can deal with an unjust system and still maintain love for those who, perhaps by training, were caught up – in the system.”

Overall, the role Jews played in the Civil Rights Movement remains a source of pride and represents a meaningful bond between two communities that continues today. While there is no longer a conflict over civil rights in the Jewish community, time and again, the Jewish people face internal strife. My hope is that the Jewish people, and all people, are able to embody Dr. King’s words in B’nai Jehudah, persevering in the fight for justice while preserving love and understanding for one another.

Originally Published Feb 9, 2022 12:03AM EST