Whatever you may have seen online, possibly tweeted by your least favorite uncle, Jewish people DO NOT “run” Hollywood. Studios today are small units of giant corporations, run by all sorts of people.

However, it is true that Jewish-Americans, many who were recent immigrants (i.e.: Carl Laemmle, Adolph Zukor, Samuel Goldwyn), were some of the founders of key Hollywood studios, along with others who were not Jewish (like Thomas Ince, Mack Sennett and Walt Disney). What inspired so many Jews to join the early film industry, and what was their lasting impact on American culture?

(Read more: Should non-Jews play Jewish roles in Hollywood?)

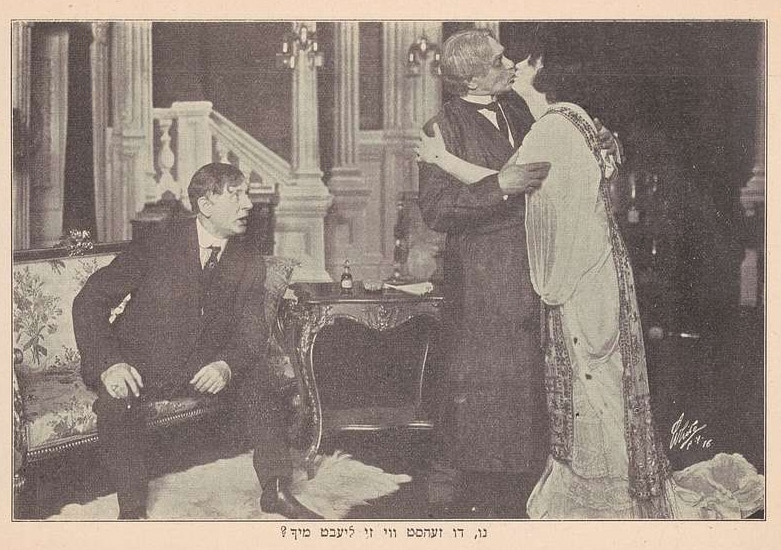

Many of these Jewish-Americans came from vaudeville and the garment trade, two industries notably hospitable to Jews. Vaudeville theaters presented variety shows: a singer followed by an animal act, followed by slapstick comedy, and so on. Theaters in immigrant neighborhoods had shows in different languages, including Yiddish. This appeal to immigrants, and low ticket prices, made the overwhelmingly white, Christian upper class look down on vaudeville, so they did nothing to keep Jewish entrepreneurs out of the business. Jewish immigrants, many of them arriving with tailoring skills, similarly thrived in the garment industry since it didn’t require much training or money to open a small clothing factory.

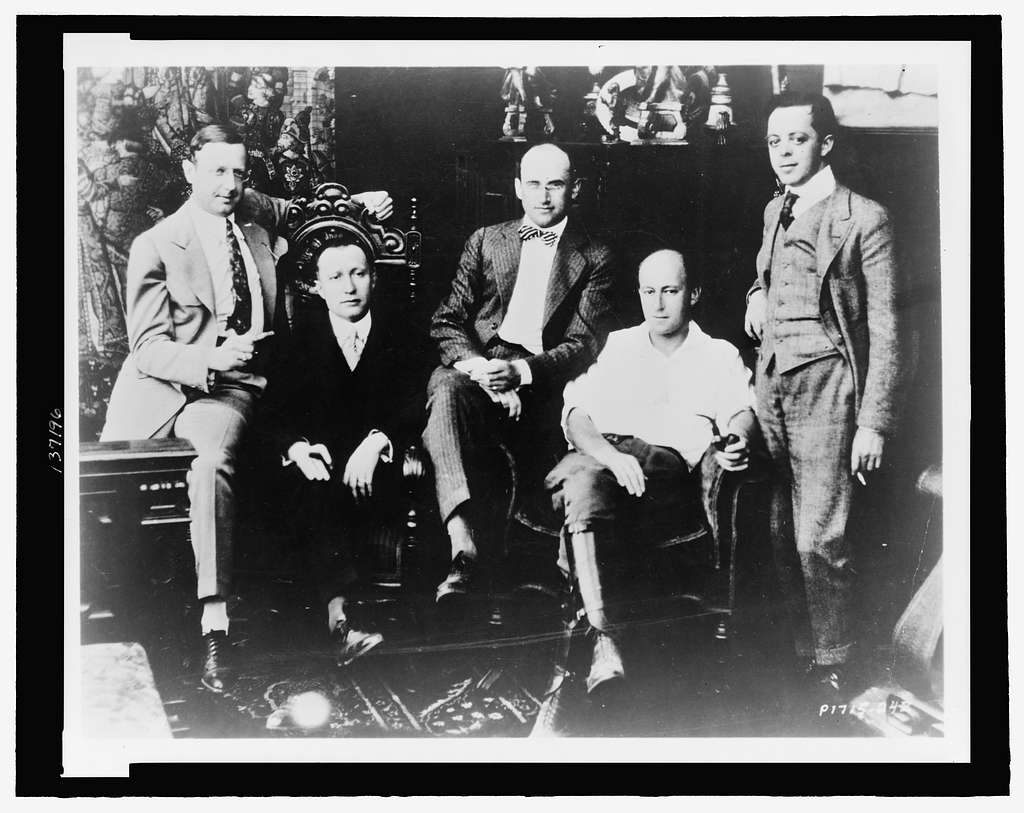

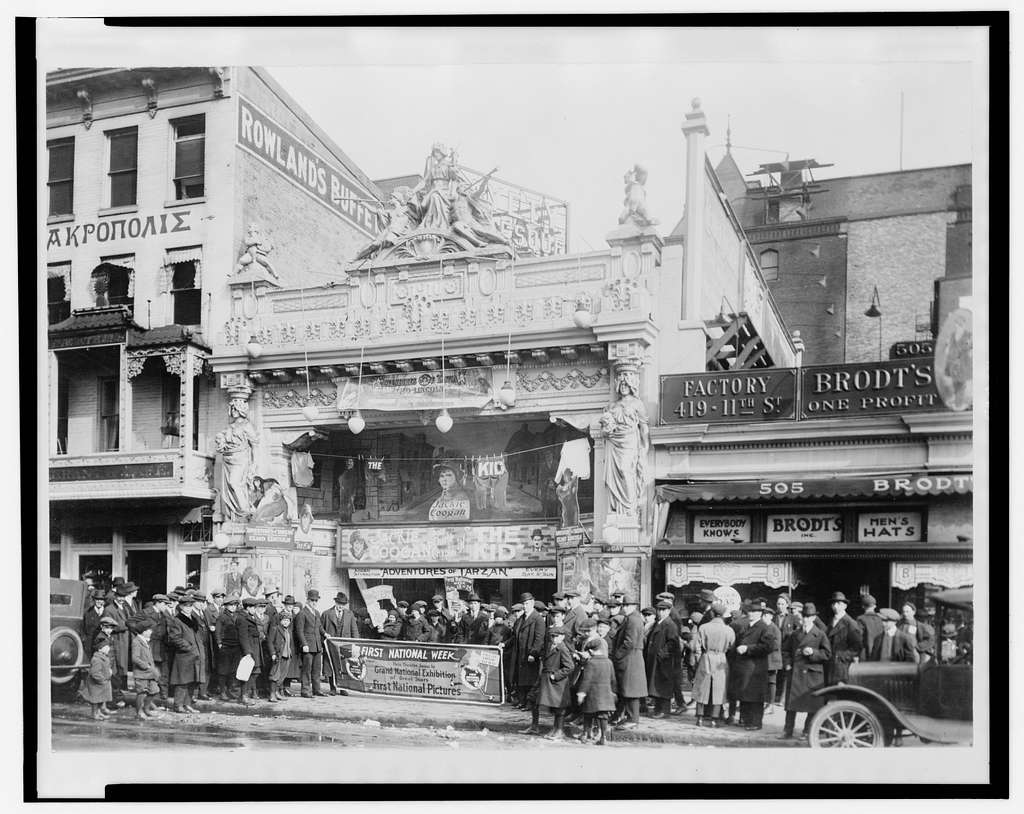

When movies were introduced in the late 1890s, success in this new industry required many of the same skills as vaudeville and the garment trade. Salesmanship was the big one: film producers had to sell their movies to theater owners, and theater owners had to then sell to audiences. For example, Carl Laemmle (a German-born Jew) marketed clothing before starting Universal Pictures. Adolph Zukor (a Hungarian-born Jew) sold furs before founding Paramount Pictures, and Jesse Lasky (an American-born Jew), one of his partners at Paramount, was previously a vaudeville horn player. And there were many others, like Shmuel Gelbfisz (a Polish-born Jew) who changed his name to Samuel Goldwyn once he quit selling gloves and entered the film business. Marcus Loew (an American-born Jew) also came from vaudeville before pivoting to movie theaters (AMC Loew’s) and production.

These Jewish-American entrepreneurs succeeded because motion pictures were widely popular and gentile industrialists largely wanted nothing to do with the business. The moviegoing audience was primarily the working-class and immigrants: tickets were cheap and silent cinema had no language barrier. This audience made the mostly-Protestant cultural elite dismiss film as “lowbrow”, and major investors considered it a passing fad. Some Catholic institutions even mobilized against motion pictures, believing they were a corrupting influence. But Jews were unaffected by Catholic teachings and mostly unbothered by this snobbery.

Instead, Jewish-Americans in the film industry were affected by other prejudices. Jewish studio owners were eager to assimilate as Americans, like many Jewish immigrants of their time. They sought to publicly embrace their American identity and leave Old World antisemitism behind, though the studio chairmen didn’t anglicize their names like some Jewish performers (Edward G. Robinson, Kirk Douglas, Lauren Bacall). In fact, studio executives’ Jewish last names were used as antisemitic dog whistles. Bigotry remained a persistent concern for the businessmen laboring to grow their production companies from tiny start-ups into the Hollywood studios still operating today.

For example, Marcus Loew bought the small studio, Metro Pictures, in 1920 to feed movies into his theaters. When Metro needed to grow to keep up with demand, Loew bought out Samuel Goldwyn’s company, Goldwyn Pictures. They later merged with another company owned by Louis B. Mayer (a Russian-born Jew). Their combined company was called Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. The head of MGM, Louis B. Mayer, was so eager to be perceived as an assimilated American, he adopted the Fourth of July as his birthday and celebrated it lavishly every year with his employees.

The movies produced by the Hollywood studios downplayed cultural and religious differences, and instead projected inclusivity onto American screens. However, social barriers around race proved much harder for the movies to overcome. Hollywood movies created a new, homogenous, white American cultural identity that was so widely embraced by the moviegoing public, it became THE American identity. The movies offered a vision of the Great Melting Pot that American society was still striving to become. Jewish creators and businessmen seeking assimilation ultimately invented the culture that defined 20th Century America; ironically, leaving it up to later generations to make that culture more inclusive of other identities such as race, gender, and sexual orientation.

Eventually, the first generation of Jewish-American studio honchos retired or passed away. Their successors faced a changing industry. By the 1960s, Hollywood studios were making fewer, more expensive films, at greater financial risk. To hedge against these risks, the studio owners sold their companies to larger corporations. Kirk Kerkorian, a major investor in Las Vegas casinos, purchased controlling interest in MGM in 1969, and Paramount Pictures was sold in 1966 to the Gulf + Western Industries Corporation, a conglomerate that included manufacturers of auto parts, clothing, and mattresses. This shift from independent businesses to divisions of larger corporations proved permanent for the Hollywood studios.

Nevertheless, the Jewish-American founders of the major Hollywood studios left their mark with the culture they created: enduringly popular movies that emphasize what’s shared in American and Jewish values, blurring the hyphen between “Jewish” and “American” until generations to come could consider these identities one and the same. They told stories about love for family, community, and country. Stories about earning an honest living through hard work, and conducting one’s business fairly. Stories about protecting the less powerful and standing up to bullies. Stories about braving the wilderness and braving a new country to find a place to call home. Stories about faith, hope, healing, truth, justice, and the American way.

Originally Published Jun 10, 2021 08:59AM EDT