Welcome to the final chapter of our three-part Yom Kippur War miniseries. If you’ve been listening since the beginning — awesome! You rock! If you’re just tuning in now, go back and listen to the last two episodes, because this one is full of spoilers. Seriously…I’ll wait.

Our first episode covered the lead-up to the war — including the post-’67 euphoria that blinded Israel to the warning signs that Egypt and Syria were poised to attack. Our second focused on the disastrous first days of the war, and the battles that turned things around. But Part Three might be the highest-stakes episode of all — a story of two superpowers playing nuclear chicken while the Jewish state fought desperately for its survival.

Chapter Three: The Halls of Power

Yom Kippur 1973. Washington DC. It was six AM — on a Saturday, no less — but already, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger was having a bad day. Just yesterday, he’d been riding the high of a productive meeting with the Egyptian Foreign Minister Mohamed el-Zayyat, who had just confirmed starting US-mediated peace talks with the Israelis next month.

But now he was being shaken awake at the crack of dawn by a cable from the U.S. Embassy in Israel that went something like Egypt and Syria about to attack STOP doesn’t look good STOP help yes/no? OVER

Okay, it turns out I have no idea what a cable is or how it’s different from any old-timey telegram thingie, but that’s how I’m imagining it, so no one correct me, k?

Kissinger immediately sprang into action. He called the Israelis, telling them in no uncertain terms not to attack first. He made contact with the Soviets, asking them to pretty please calm things down. He reassured the Egyptian ambassador to the U.N. that the Israelis wouldn’t attack first, so could Egypt please just chill? And finally, he sent messages to the Jordanian and Saudi kings asking them to help moderate. Like, c’mon guys. Let’s not do this.

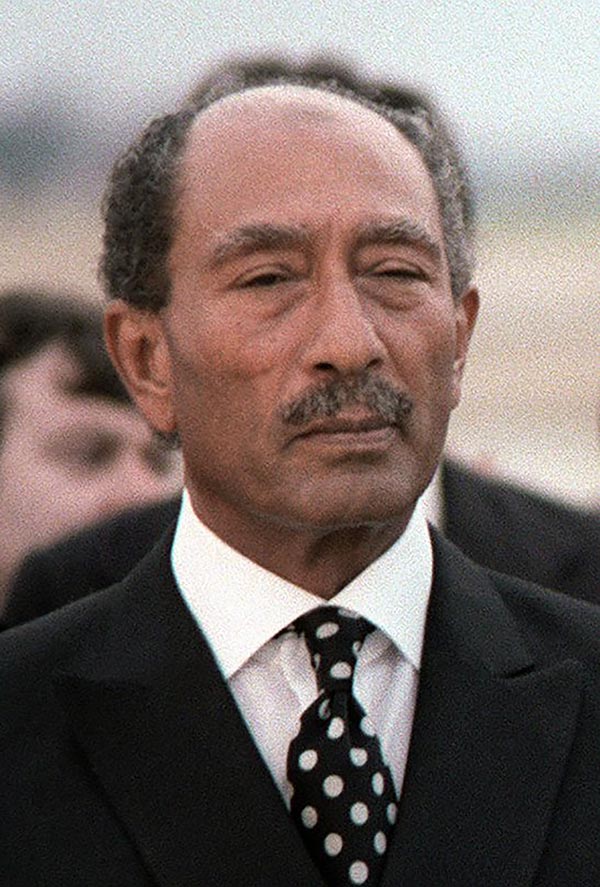

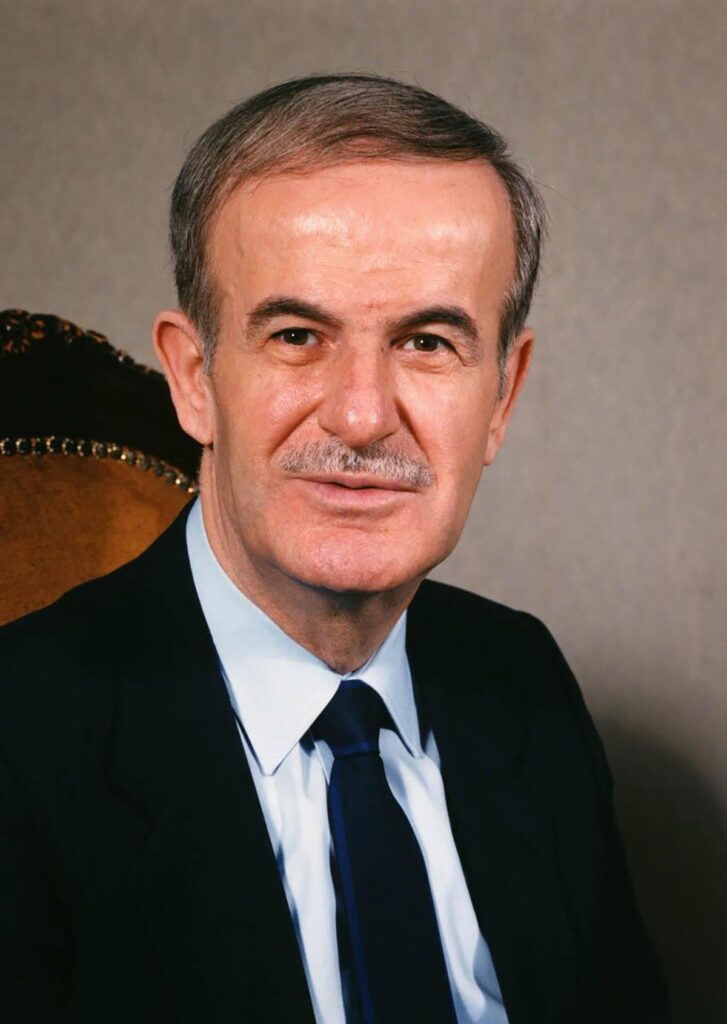

But when Middle Eastern dictatorships are feeling frisky, very few people can stop them from doing what they want, and that includes the US Secretary of State. (Because let’s be real — Sadat and Assad were both in the Soviet camp. Or so everyone thought…)

Less than two hours after Kissinger received that initial cable — despite the desperate flurry of calls in that time — he got another unwelcome update. Egypt and Syria had attacked. War had begun. And it threatened both to upend the US’s ambitious Mideast peace plan and potentially set the entire world ablaze.

Wow, Noam, dramatic much?

Well, yes, because I’m a podcast host and it’s kind of my job to get our audience invested, so…those Apple reviewers who say I could be a bit passionate and intense at times…Feedback heard, but I’m gonna stick with it because nothing I’ve said is an exaggeration. Because remember: we’re in the middle of the Cold War. So this wasn’t just a conflict between Israel, Egypt, and Syria. If the two superpowers didn’t restrain themselves, they risked shattering their uneasy detente and dragging the entire world down with them.

Their uneasy what now?

Nerd corner alert: Detente is a fancy French way of saying that things weren’t as bad as they could have been. No, seriously, it literally means “loosening” or “relaxation.” Both superpowers were acutely aware that their, uh, let’s say polite disagreements could very well lead to a global nuclear holocaust. In 1968, they agreed to a Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, ushering in a period of — if not warmth, then at least a distinct thaw in their relationship.

They even signed a Strategic Arms Limitations Talks agreement in 1972! To simplify drastically, these agreements signaled that both countries were committed to making sure that the Cold War didn’t turn hot, and by hot, I mean nuclear.

But now, the Yom Kippur War threatened to put this detente to the test. Could the Americans and the Soviets work together to convince their respective allies-slash-clients-slash-proxies to chill the f out? Or would diplomacy fail, miring both global superpowers even deeper in conflict?

For the first couple days of the war, both Washington and Moscow expected another miraculous ’67-style victory. In fact — and this is fascinating to me, I hope it’s fascinating to you — Moscow was even actually kind of hoping that the Israelis would show Egypt’s president, Anwar Sadat and Syria’s president, Hafez al-Assad, a thing or two. The two Arab leaders had ignored all of Moscow’s warnings to just be cool. So the Kremlin was kinda looking forward to kicking back and watching the two strongmen get a lesson in humility, courtesy of the legendary IDF.

Nerd corner alert again, and you’re going to be hearing lots of those: if you’ve been paying close attention, then this probably sounds like a total reversal in Moscow’s attitude towards Israel. After all, the Soviets were not thrilled about Israel’s miraculous victory in 1967.

But both Washington and Moscow were in for an unpleasant surprise. Because if you’ve listened to our last episode, you know that the first few days of the war did not go particularly well for Israel.

As the war unfolded, the Israeli ambassador flooded Kissinger with increasingly desperate pleas for more weapons. Which put Kissinger in an uncomfortable position. On the one hand, he didn’t want to alienate the oil-rich Arab world, or risk shattering the fragile detente.

On the other, he had grand plans for a US-brokered peace deal — one that required the Israelis’ trust. He initially tried threading the needle by discreetly sending some arms to Israel in El Al planes, but as the Israeli requests for arms became increasingly desperate, he held off on significant — or public — shipments.

In fact, Kissinger was trying to balance against another, surprising consideration. On the second day of the war, he received a message from Sadat. On the surface, it was nothing remarkable: if you want this war to end, then the Israelis have to withdraw to ’67 borders; Egypt won’t back down from this position, etc. etc.

But underneath this standard-issue bluster was a radical message — an assurance that Egypt had no intention of “deepening the engagements or widening the dispute.” Sadat’s predecessor, Gamal Abdel Nasser, had been distinctly resentful of the US. But Sadat’s message to Kissinger, though subtle, was clear: we have no beef with you. Egypt was turning away from the Soviet Union and towards the US. And that gave the US an opening to broker not only a ceasefire, but a lasting peace agreement. All of this was absolute catnip to an American Secretary of State.

But three days into the war, neither side was ready for a ceasefire. Elated by his early successes, Sadat wanted to press his advantage. And Israel — which was bleeding — needed some kind of victory if it wanted to keep even a shred of deterrence intact.

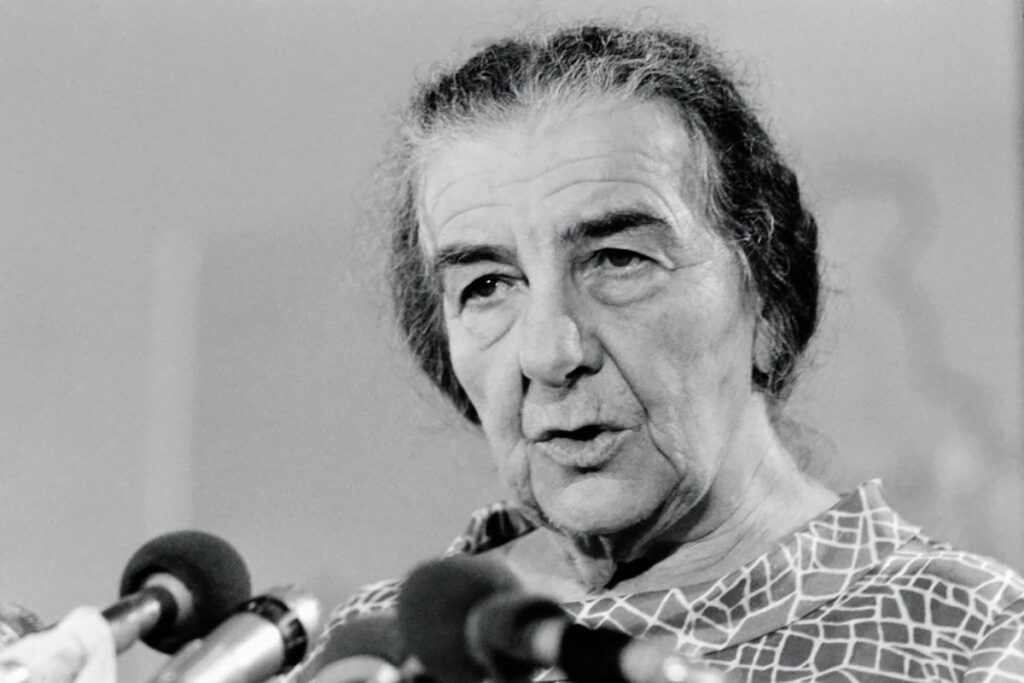

By the end of the fourth day of the war, Israel was down an eighth of its airforce and a quarter of its armor. The Americans had promised to replace all of Israel’s lost weaponry, but they seemed to be dragging their feet. So Golda Meir made a hail-mary proposal. What if she flew to Washington to ask Nixon for help in person? But Kissinger nixed that idea immediately. No way, he said. Did she really want everyone to know how desperate her country was?

Golda didn’t go to Washington. And Israeli casualties kept piling up.

By Day 4, the IDF had pretty much pushed the Syrians out of the Golan, but the southern front was still on fire. And all signs pointed to the Syrians regrouping, thanks to a generous resupply from the Soviets. True, Moscow hadn’t been thrilled with Egypt and Syria for poking the hornet’s nest. But to everyone’s surprise, the hornets seemed much weaker than usual. So as Egypt pressed its advantage on the battlefield, the Soviets found themselves, well, kinda thrilled. Look at what the Egyptians were doing with all that Soviet weaponry! Back in ’67, they’d embarrassed themselves – and, by extension, the USSR. But who was getting humiliated now, huh?

So even as they promised to help the Americans negotiate a ceasefire, the Soviets were encouraging Sadat to keep pushing. Worst of all, they’d placed their own jets on high alert — an ominous signal that Soviet soldiers might join the fight.

Well. Washington wasn’t going to take that lying down. Kissinger warned the Soviet Ambassador that if they got directly involved, the U.S. would respond in kind. At this point, he was all but ready to give up on detente. As he wrote later, quote, “Once a great nation commits itself, it must prevail.”

Is your head spinning yet? Because the rapid-fire changes are giving me whiplash. Let’s just recap for a second:

- The U.S. and USSR had tried to prevent the war by urging both sides not to attack.

- When the war started, both were kinda rooting for Israel — the U.S. because it wanted to stick it to the USSR, who had armed the Arabs, and the USSR because it was ticked off at Sadat and Assad.

- But as the war dragged on and Israel suffered catastrophic losses, the USSR changed its tune, egging on the Arabs even as Sadat was sending secret messages to Kissinger that signaled that he’d be open to parlaying with the US.

- Meanwhile, as Israel begged its strongest, and let’s be honest, only real, ally for weapons, Kissinger held off, not wanting to risk detente or alienate the Arab world.

- It was only when the Soviets started re-arming their clients that Kissinger decided screw detente, I’m not letting the USSR get away with their nonsense.

Guys. Seriously. What is this? What even IS geopolitics? It’s nuts. There are like human beings here who are being affected on the ground…This is all so complicated, my head feels like it’s going to explode. Can you imagine what would have happened if the US and USSR had come to blows on the battlefield?

I can. Two words: nuclear winter.

But luckily for the entire world, the Soviets weren’t quite ready to call all-in and see whether Kissinger was bluffing. They had significant incentives to keep being the US’s frenemy. Like, for example, their crumbling economy – and the possibility of some attractive trade agreements with the US.

Nerd corner alert…so many!: those trade agreements ultimately never came to pass thanks to a little something called the Jackson-Vanik Amendment in 1974. Doesn’t sound familiar? Well then, go back and listen to our episode on Soviet Jewry.)

So despite their belligerent rhetoric and their extensive military aid to Syria, Soviet leaders eventually agreed to a ceasefire in the most hilariously petulant way possible. No, seriously, listen to this language. They were, quote, “ready not to block the adoption of a ceasefire resolution” at the UN. Gotcha, thanks, Soviets.

The war was six days old. The Americans were urging a ceasefire. The Soviets agreed. And the Israelis, who had been reluctant at first, were on board too.

But Sadat continued to refuse, pushing for one last offensive in the Sinai to break Israel’s momentum. So he wasn’t gonna stop now.

There’s no record of this, but I am fully prepared to bet that when Kissinger heard of Sadat’s refusal, his first reaction was GAHHHH.

It was time to get the U.S. President involved. President Nixon was, shall we say, preoccupied, dealing with both the fallout from Watergate, and his vice president’s resignation that same week(!) on charges of tax evasion and accepting bribes. That’s a rough week.

But though his life may have been in shambles, there was no way Nixon was going to let the Kremlin get away with winning a war in the Middle East. No way! The Soviets wanted to arm the Arabs? Fine. Then he would arm the Israelis. The Arabs wanted to play ball? No problem, American weapons would help even the score. And everyone knew that when Israel played ball, they played to win.

So on October 13th, one week into the war, Nixon okayed Operation Nickel Grass (no, not Nickelback, nickel grass…dad joke), which brought literal tons of American weaponry into Israel.

Nixon and Kissinger were well aware that this public show of support would alienate the Arab world. They were prepared for the possibility of an oil embargo. Europe, however, was not. And that presented the U.S. with a bit of a problem. U.S. cargo aircraft couldn’t fly directly to Israel without needing to refuel. Spooked by the possibility of an oil embargo, no European nation wanted to be seen helping America help Israel. So every US ally on the entire freaking continent refused to allow US planes to refuel on their territory en route to Israel. Well, every country but Portugal. And that’s only because Kissinger sent a spicy letter threatening, and I quote, “to leave Portugal to its fate in a hostile world.”

Savage.

The first major shipment of Operation Nickel Grass arrived in Israel on October 14th. But by then, as you know, Israel had pushed back the Egyptians. And now that the IDF was in a position of strength at last, it was Jerusalem that had no incentive to accept a ceasefire. In fact, those crazy kids were planning to cross the Suez Canal and invade Egypt proper.

Meanwhile, the Arab world was fuming. On October 17, as Israel was — and please excuse this fancy military terminology — kicking serious butt at this point, the Arab countries began that embargo that had so spooked Europe. By October 20th, the Saudis announced a 10% cut of oil production, and reiterated that they’d be embargoing all oil shipments to any country that supported Israel (not that there were that many, TBH).

In the US, the price of oil quadrupled. Gas became both scarce and ridiculously expensive. (Nerd corner alert, and this is insane: Nixon even debated sending the military to seize the oil fields of the Gulf states. Luckily, the embargo ended through peaceful means before he could start another war halfway across the world.)

You’d be forgiven for asking, would the US still have helped Israel if they knew this was the price? And while I can’t answer that with any certainty, my gut feeling is absolutely, yeah. Because the Yom Kippur War was just as much about honor as it was about land. The Egyptians and the Syrians — and by extension, the USSR — wanted to feel, well, less humiliated. The Americans wanted to show the Soviets that they were the biggest, baddest wolf in the forest. And that meant they weren’t going to back down from the USSR or be held hostage by the Arab world. And Israel? Well, Israel learned a hard lesson about honor, too. But we’ll get there.

Sadat may have regained Egyptian honor and pride in the first days of the war, but by October 22, he finally admitted that it might, after all, be a good time for a cease-fire. Sixteen days into the war, the U.N. Security Council passed Resolution 338, calling for a ceasefire and commencement of negotiations.

Crucially, though, the ceasefire wouldn’t go into effect for 12 hours. And the Israelis planned to use every single one of those hours to break the back of the Egyptian army. Sadat, in the meantime, had a plan of his own. Yes, his position was bad. But he could still fire a couple of Scuds into the battle zone, just to show that he could.

No one agrees how many Scuds were actually fired. Sadat’s memoirs say two. Egyptian Army Chief of Staff General Shadhly reported three. The Israelis say just one. Regardless of the number, at least one missile cost the lives of seven Israelis. And the Egyptians weren’t done yet. Minutes before the ceasefire went into effect, the Egyptians strafed the Israeli army with artillery, mortars, and rockets, killing sixty soldiers.

The ceasefire didn’t hold. Through the night, the Egyptians fired RPGs and bullets towards Israeli tanks, and the Israelis fired back. Frustrated with the Egyptian interpretation of “ceasefire,” Dayan okayed an assault in the southern sector, aimed at blocking the road between Cairo and the Suez.

On the northern front, Assad was making plans of his own. Sure, the Syrian army had taken a beating. But the Syrian president had bolstered his forces with some Palestinian commandos, as well as troops from Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Morocco. Compared with Israel, he had five times the tanks and four times the men — odds that might even regain him the Golan. He planned to attack on the morning of October 23, while Israel was distracted on the southern front.

But the fight never happened. Assad understood that if he attacked, Israel had the power to completely destroy the Egyptian Third Army. With Egypt’s military in shambles, it could no longer come to Syria’s aid if the Israelis turned towards Damascus. Reluctantly, Assad accepted the ceasefire that he had so vehemently refused — quite a lesson in humility for a man who had vowed to regain the Golan.

The fighting in the north was over. But the fighting continued in the south, as the IDF pinned the Egyptian Third Army between the Suez Canal and Israel’s 401st Armored Brigade.

With his army now entirely cut off, Sadat begged Kissinger to enforce the cease-fire by any means necessary — including use of force. The Soviets backed him up, ending their message with an unmistakable threat. “If you find it impossible to act jointly with us in this matter, we will be faced with the necessity urgent to consider taking appropriate steps unilaterally.”

In other words, call off the Israelis or we’re getting involved. And during the Cold War, them’s fighting words.

The U.S. sprang into Defcon-3 — the highest level of alert during peacetime — meaning, if necessary, the Air Force would be able to mobilize in 15 minutes. In the meantime, the U.S. sent Sadat a message asking him to please reconsider asking the Soviets for help. When the U.S. sends you a message that reads, quote, “I ask you to consider the consequences for your country if the two great nuclear countries were thus to confront each other on your soil,” you should probably listen.

But the U.S. wasn’t going to leave everything in Sadat’s hands. Knowing that Soviet intelligence was watching, the Americans began preparations for war — which included bolstering their Mediterranean fleets and repositioning B-52s with the ability to carry nuclear bombs.

NUCLEAR. FREAKING. BOMBS. WHAT!

Finally, through the Israeli ambassador, Kissinger sent Golda Meir an astonishing message. If you had to completely destroy the Egyptian Third Army, could you do it? And Golda, shocked, said yes.

The (nuclear) ball was now in the Soviets’ court. But the USSR had no intention of going to war with the U.S. over Egypt and Syria. Hadn’t they told Egypt and Syria to freakin’ cool it before the start of the war? They definitely had. Now, it was time to tell them, We told you so. But before the Soviets could tell Sadat anything, he reached out first, canceling his request for Soviet troops. Instead, he’d ask the U.N. to send a peacekeeping force.

The crisis was averted. Now, everyone involved just had to figure out how to make peace.

But the Egyptian Third Army was still under siege in the Sinai. And here is the weirdest and most touching story of the war for me. Despite the ceasefire, Egyptian and Israeli soldiers were still sniping at one another. At the edge of Suez City, an Israeli tank battalion traded shots with Egyptian commandos until UN peacekeepers intervened. The Egyptians were the first to lay their weapons down. And then, they did something…kind of incredible.

Defenseless, they crossed U.N. lines and approached the Israelis. The company commander radioed his lieutenant colonel to report that Egyptians were crossing over in droves. The commander ordered him to take them all prisoner. But the soldier corrected him. “They don’t want to surrender. They want to shake hands.” As their officers bellowed for them to come back, the Egyptian soldiers kissed the Israelis they’d been shooting at just moments before.

You can’t make this stuff up.

A similarly touching scene played out further along the Suez, when an Israeli paratroop company stationed near Ismailiya came across a group of Egyptian commandos. The Israeli captain braced for confrontation, shouting “Cease-fire! Peace!” But the Egyptian company commander told the Israelis that he had no intention of violating the ceasefire. But what he said next shocked the Israelis. “Sadat wants peace with you,” he informed the Israelis. Not just a ceasefire. Peace.

He was right, by the way. The two countries wouldn’t sign a peace treaty until ’78. But in the meantime, the two companies made a peace of their own, meeting up each day to make coffee and play games and talk about girls. They even held joint kumzitsim — an untranslatable Yiddish word for “singing spiritual songs around a campfire,” and yes, this is a real thing, and no, I’m not making this up — though I do wonder what songs the two companies had in common.

The Egyptians would bring freshly slaughtered sheep. The Israelis would bring their care packages from home. And me? I’m bringing my feelings to this freaking crazy, beautiful, tragic, messed up story. Because don’t these coffee dates and backgammon tournaments and soccer matches and kumsitzes suggest that we could have had this all along? Why did so many people have to die before we recognized each other as human?

It was a question that rang throughout Israel. Why did so many have to die?

And it wasn’t going away. Four months after the war, Motti Ashkenazi – who had commanded the only Israeli fort along the Bar-Lev line that didn’t fall to the Egyptians – stood outside of the Prime Minister’s office holding a sign that read Grandma, your Defense Minister is a failure and 3,000 of your grandchildren are dead.

Nerd corner alert: He wasn’t far off: Israeli casualties numbered 2,656 dead and 7,250 wounded — triple the death toll of the Six-Day War.

Every day, more people joined his silent protest. By March, more than 5,000 Israelis showed up to demand that government officials resign. Everyone knew someone who had died or been terribly wounded or taken prisoner. Worst of all, everyone knew that so many of those deaths could have been avoided, if Israel had just been better prepared.

Prime Minister Golda Meir was well aware of the precarity of her position. Less than a month after the ceasefire, her government appointed a five-man commission, led by Shimon Agranat, president of the Israeli Supreme Court, to investigate why Israel had been caught so wrong-footed.

So who was responsible? Well, I’ll start with who wasn’t, according to the Agranat Commission: Defense Minister Moshe Dayan and Prime Minister Golda Meir. Instead, the commission placed the blame on the IDF Chief of Staff, as well as four high-level intelligence officers, recommending that all five be dismissed.

As for the sixth guy, the former chief of the southern command — well, the Commission wasn’t entirely sure about him yet, so they recommended he be suspended until they could finish their investigation. The public was enraged. Were the Defense Minister and the Prime Minister really going to get off scot-free?!

They weren’t. A week after the Commission released its findings, Golda Meir announced her resignation. Her entire cabinet would step down with her.

But none of this erased the cost of the war for the Israeli public. The wounded were still in recovery. The dead, still dead. The POWs, some who had been tortured and beaten in Egyptian and Syrian captivity, would carry the physical and psychological scars forever. And the vision of Israeli invincibility? That, too, was shattered.

In the background, you can hear the opening strains of Choref 73, Winter 73, written in 1993 to commemorate the sad winter that followed the war. Its writer, Shmuel Asfari, had lost his best friend, Yoram Weiss, on the battlefield. The chorus goes something like this: “You promised a dove/an olive leaf/you promised peace/You promised spring at home and blossoms/You promised to fulfill promises, you promised a dove…”

But 20 years after the war, and the grown-ups were still breaking promises. Asfari explains: “I went back home [after visiting Yoram’s grave], and it was pouring rain, and on the way home they reported that the hopes of the Oslo Agreements that broke through only a few months before probably wouldn’t work out. There were big arguments between Rabin and Peres and Arafat and Clinton, and the whole thing is about to collapse at any second. I got home in a terrible mood. I put the kids to sleep and I went to my room. And this song really wrote itself. I don’t remember myself sitting and writing it, or looking for the words. I just remember that the kids of winter ’73 — I thought about the kids I was working with at the time, who were in the military band. Those are the kids born after the war. And they’re in the army. And nothing has changed.”

We can certainly forgive Asfari for his cynicism. But I don’t agree. Because at least one thing changed in the wake of ’73. Egypt and Israel signed a peace treaty — one that’s held through multiple conflicts with other neighbors.

And maybe that’s why Avraham Rabinovich calls the war “a terrible war with a perfect ending.” Rabinovich also claims that far from diminishing the IDF’s reputation, the war actually burnished its mighty legacy. The Jewish state began the war on its knees and ended it less than three weeks later with its tanks pointed toward enemy capitals.

But the country paid dearly for this victory. And many of the soldiers who returned from war or captivity lost something. Limbs. Eyes. Friends. Brothers. Innocence. Hope. For decades, veterans of the war didn’t talk much about their experiences. Trauma tends to leave people pretty tight-lipped. But recently, TV shows like Sha’at Neilah, or Valley of Tears in English, have inspired a national conversation about the war’s legacy.

We asked Avigdor Kahalani, hero of the actual Battle of the Valley of Tears, how he felt seeing his story play out on the small screen. “When I saw the movie, they changed many facts and they’ve done many things. In fact, it’s Hollywood. But the result of this war, this movie, they gave the feeling of the new generation and the third generation, suddenly they saw what happened during the war and they start to ask questions about the Yom Kippur War.” “And this is good for us from my point of view that people ask many questions. What happened? Why?”

It’s knowledge that saves us from apathy. That reminds us of the stakes. I hope Israel never ever has to fight another war like Yom Kippur ever again. But if it does, I like to think that the Jewish state will be ready.

So there you have it. That’s the end of the Yom Kippur War, three episodes. And if you’ll indulge me, here are six fast facts — two per episode.

- On Yom Kippur, October 6, 1973, Egypt and Syria attacked Israel on two fronts, in an attempt to regain the territory they’d lost during the Six Day War of 1967.

- Israel was unprepared for the attack, convinced that the Arab nations wouldn’t dare come back for more after their spectacular humiliation six years earlier.

- The first three days of the war were particularly brutal, claiming over one thousand Israeli lives.

- Nuclear tensions between the US and USSR were at an all-time high. Though the US was initially reluctant to help Israel, President Nixon sent Israel a massive weapons shipment when he learned that the USSR had resupplied the Arabs.

- Thanks to a few miraculous battles, Israel ended the war 50 miles from Cairo and 25 miles from Damascus.

- Despite this astonishing military victory, the war left a deep scar on the Israeli psyche – one that has still not healed.

Those are your six fast facts, but here’s one enduring lesson as I see it.

What do people do after a crisis? That’s a real question. Seriously! What do you do when everything you thought you knew has been turned on its head? When your illusions are shattered, when your hope is gone, when there’s nowhere to go but forward, because the road back home has been destroyed?

Well, it depends. Some people break entirely, questioning their very existence. Why am I still alive? What’s the point of all of this? What am I even sacrificing for?

But some find their answers where they least expect them. For over 25 years, Israelis had done their best to become New Jews. Strong. Self-sufficient. Secular. Who needed God, if you had muscles and wits and the will to work hard?

God was a diaspora idea, a fairy tale that scared children told themselves to ward off the dark. But now that they had their own state, Israelis could ward off the dark just fine on their own, with guns and tanks and even nukes, if it came to that.

The Yom Kippur War shattered those illusions. Sure, Israel “won.” (And yes, scare quotes there, as we’ve talked about.) But the price of victory was certainty. The New Jew was a comforting fiction that Israelis used to reassure themselves that they’d never be kicked around again. But the Yom Kippur War exposed it for the lie that it was. Sure, the Jewish people had a state full of strong, brawny men and women who worked the land and wielded a gun with equal fervor.

That hadn’t stopped their enemies from attacking on the holiest day of the year. Just like in the Diaspora — a Jewish holiday, used as an excuse to attack. And now, nearly three thousand of Israel’s sons were gone.

Where do you go, when your comforting fictions no longer hold up? When your personal Bar Lev line has been breached? When fathers and sons wind up on the battlefield, fighting and sometimes dying side-by-side? Where do you go when your certainty is gone?

Ironically, that’s when you turn to faith. Daniel Gordis writes about the aftermath of the Yom Kippur War, quote: “The absolute rejection of religion and the utter commitment to secularism of the founding generation began to give way. It was too early to tell then, but Israel was going to move away from its early image of the new Jew — secular, confident, dismissive of religion — and would begin to search for meaning in places that previous generations would have dismissed out of hand.” Like religion.

Few places are more secular than your classic Israeli kibbutz — the socialist agricultural collectives that bred so many of Israel’s ruling elite, including Moshe Dayan. And few places embody Israel as much as the kibbutz. They’re small, tight-knit, familial — Israel writ small.

It was a kibbutz that symbolized the depth of Israel’s loss. Kibbutz Beit Hashita in northern Israel lost 11 men. The Canadian-Israeli journalist Matti Friedman writes: “One day after the war’s end, 11 small army trucks pulled through the kibbutz gates, headlights on even though it was daytime. Each bore one coffin. The dead men were the kibbutz’s next generation — young workers and fathers, most of them reservists. For a small and tightly knit community, it was a nearly incomprehensible loss.”

Eleven men. The highest losses per capita of any Israeli community. It was a loss that would haunt Israel for decades. In 1990, one of Israel’s most famous songwriters came to stay at the kibbutz. And it was in honor of the 11 men who had fallen that he composed a new tune for an ancient prayer. No one knows the exact origin of the Yom Kippur prayer Unetanah Tokef. But everyone knows that it symbolizes the fragility of human life before a divine creator.

As Matti Friedman writes: “The text of the prayer could not have been farther from the kibbutz’s militantly secular approach to Yom Kippur, which members had marked as a day of meditation and honoring the dead that had nothing to do with a God whose nonexistence they considered to be an article of faith.” And yet, the composer “introduced an unapologetically religious text into a stronghold of secularism and touched the rawest nerve of the community, that of the Yom Kippur war,” with “overpowering” results.

Just one of the changes sparked by the Yom Kippur War. But there were others, too. And that’s why I’m returning to a Biblical parallel.

The book of Numbers, aka Bamidbar, and I find this fascinating, recounts the following story. As the Israelites draw close to Canaan after 40 years of wandering the desert, they send a group of 12 spies — one from each tribe — to scout out this Promised Land. But 10 of the 12 spies come back with a devastating report. Sure, they say, the land is flowing with milk and honey. But it’s also lousy with multiple enemy tribes, some constituted by giants who make the Israelites look like grasshoppers. (Weird simile, but okay, it’s in the Bible.) The two spies who disagree are shouted down.

The Israelites are bummed. They immediately start kvetching in the most dramatic way possible. “You should have left us to die in Egypt, it’s better to die in the wilderness, why are you taking us to this promised land only to die by the sword,” etc. etc. etc. I don’t know why I did a New York accent, but I had to. Moses and Aaron try to placate the mob. God, on the other hand, is steaming. The doubters get punished, by which I mean that God makes good on his promise to “drop their carcasses in the wilderness.”

Eesh. The lesson is clear. No faith, no Promised Land. But as you know, the Israelites do eventually make their way to Canaan, led by Joshua — one of the two spies who had urged them to keep the faith. And at first, everything seems hunky-dory. Sure, the land is full of enemy tribes. But the Israelites are ready to take them on, starting with the walled city of Jericho.

For six days, the Israelite army circles Jericho, carrying the Ark of the Covenant and blowing the shofar – which, side note, sounds legit terrifying for the people under siege. On the seventh day, the walls of Jericho crumble and the Israelites rush in and take the city.

It was a stunning victory. But it came with a harsh lesson. See, Joshua had warned his men not to take anything from the city. No gold. No silver. No animals, no nothing. All the spoils were for God and God alone. But it only takes one guy to ruin it for everyone. So when some guy named Achan the son of Carmi helped himself to some of the loot, God was so ticked off he decided to teach all the Israelites a lesson.

Delighted by their easy victory at Jericho, the Israelites moved on to a place called Ai. As before, they send spies to check it out. And this time, the spies come back with an overly optimistic report. So the Israelites sent a small force, confident in an easy victory.

Do you see where I’m going with this? The people of Ai – Ai-ites? – mess them up, and Joshua freaks out. He lies on the ground, calling out to God, “When the other nations hear about this, they’re gonna destroy us! Our deterrence is gone!”

And God is like, yeah bro, this is what happens when you don’t listen. You want victories? Fix your life. It’s more respectful than that, but you get where I’m going. And because this is the Bible, “fix your life” means punishing the Israelites who were collectively ethically responsible for Achan’s actions as Micah Goodman beautifully describes. So, what happens? The second time around, the Israelites meet the Ai with a much bigger force and win.

What does any of this have to do with the Yom Kippur War? Well, think about it. The battle of Jericho is the Six Day War. It’s quick. It’s easy. And it results in a sense of euphoria that blinds the Israelites to the remaining threat. And the first battle with Ai? That’s the war of ’73. The Israelites paid for their overconfidence with their lives.

And that klepto, Achan, the son of Carmi? Who’s his parallel? That would be the Israeli establishment in the lead-up to the Yom Kippur War. In this analogy, Achan is the Chief Intelligence Officer who ignored warning after warning. He’s every general that sent his men into battle unprepared. He’s Moshe Dayan, refusing to mobilize troops in time. In other words, he’s the tiny group of army and government officials whose hubris and inaction and bad decisions led to 2,656 deaths. And the Israelites then…those are the Israelis of 1973. The Jewish people who felt they became invincible.

Harsh, I know. But also, I think, true. I came to this conclusion after reading this book of Micha Goodman’s.

So what do these parallels teach us? Well, a few things. The story of the spies teaches us that we can’t see ourselves as weak. If we don’t believe in our own strength, we’re toast. Without faith – in God, in ourselves, in the long arc of justice – the Jewish people wouldn’t have a state at all. But we also can’t be blind to our own flaws. We can’t look at our victories as proof of our invincibility.

So, sure, you could ask “Did Israel win the Yom Kippur War”? But I don’t think that’s a useful question. Instead, I’d ask what did Israel learn from the war? Is Israel the giants, or the grasshoppers? Are their adversaries Jericho, or are they Ai?

And as we researched these three episodes, I found my answer in the orchard of Ismailiya, where Egyptian commandos and Israeli paratroopers met to brew coffee and kick around a soccer ball. I found it on the sands of el-Arish, where in 1979, Israeli and Egyptian veterans fell on each other not with weapons but with hugs and kisses and cries of “to life, l’chaim!” And I keep finding it in the eyes of the dreamers and the visionaries who believe that another world is possible, and who fight every day to bring us all just a step closer to it.