The coolest thing about history is that so much of it is connected. That the story of the creation of the modern state of Iraq is also a story about 2,600 years of Jewish life. About Zionism, and Israel, and the Holocaust, and the sometimes-contentious narrative of Jews in Muslim lands.

And in today’s episode, we’re going to unpack all of these stories.

Like – how the Jews got to Iraq in the first place, and why they stayed for so long.

And why Iraq, which had once been good to its Jews, turned on them so quickly, in a devastating 1941 riot called the Farhud.

And why I, Noam, have a somewhat controversial opinion about a longstanding historical debate.

But as you already know from listening to three seasons of this podcast, history is a tangle of interconnected stories, not a linear chain of cause and effect. The story of the Farhud is actually six separate stories, each looping around the other. And the only way to unpick the wild snarl of factors that led us to the riot of June 1941 is to start four thousand years ago, with a man who heard the voice of God…

Story #1: Welcome to Iraq

Almost as soon as Abraham is introduced to us in the book of Genesis, God tells him to leave his home in what is now southern Iraq and set up shop in Canaan, aka modern-day Israel. Eventually, just as God promised, Abraham’s descendants become a nation: They take on a communal identity. They’re told to practice a single, unifying religion. They establish a monarchy. And they worship in their crown jewel: Solomon’s Temple, center of religious life.

But the Kingdom of Judah was small. And the empires of the ancient Near East were so, so big. And so, so mean. So when the neo-Babylonians showed up in 587 B.C.E., they weren’t paying a social call. They destroyed the Temple, tortured the king, burned Jerusalem to the ground, and hauled off most of Judea’s Jews to exile in Babylonia… aka modern-day Iraq.

The Jews, understandably, were pretty pretty pretty unhappy about this. The Biblical Psalmist laments: “עַ֥ל נַהֲר֨וֹת ׀ בָּבֶ֗ל שָׁ֣ם יָ֭שַׁבְנוּ גַּם־בָּכִ֑ינוּ בְּ֝כְרֵ֗נוּ אֶת־צִיּֽוֹן – By the rivers of Babylon/ there we sat/ sat and wept/as we thought of Zion…”

It’s a pretty inauspicious beginning to the remarkable 2,600-year-old legacy of Jewish life in Iraq. But the Jewish exiles wouldn’t weep for long. Because just 50 years later, the Achaemenids came along, incorporated Babylonia (today’s Iraq) into their empire, and told the Jews they could go back home.

But the Bible doesn’t call us the “stiff-necked people” for nothing. Because when confronted with the possibility of rebuilding their previous home, most of Babylonia’s Jews chose to stay put. Which made Biblical leaders Ezra and Nehemiah – the two leaders who supervised the Jewish return to Judea – very, very salty. But no amount of hectoring could bring back all of Babylonia’s Jews. So the two Jewish communities developed in tandem: one at home in Judea, and one in voluntary exile in Babylon.

But exile hits different when it’s a conscious choice. Between 70 and 135 CE. – 600 years after the destruction of the First Temple – the Jews of Judea, aka Israel, were unwillingly displaced yet again, when the Romans besieged Jerusalem, destroyed the Temple, suppressed a few Jewish rebellions for freedom, and sent most of Judea’s Jews into an exile that would last 2,000 years.

Many of the exiles ended up back in Babylonia, joining a thriving Jewish community that quickly became the center of global Jewish life. It was there that rabbis compiled the Babylonian Talmud, which parsed and codified the rules for every aspect of Jewish life. The great Babylonian academies of Sura and Pumbedita churned out generation after generation of Jewish luminaries. Slowly, the Jewish people fanned out across the world, transplanting their customs in new ground. But many of Babylon’s Jews remained. And that is the story of how the 2,600-year-old Iraqi Jewish community came to be.

Story #2: I pick a bone with historians

Until the 7th century C.E., Iraq’s Jews lived among Persians and Arabs, Kurds and Greeks, Zoroastrians and Christians. But everything changed with the rise of Islam. By the year 638, Iraq lay in Muslim hands. Soon after, Gulf Arabs began to stream in. And 1,500 years later, historians argue about what all this meant for Iraq’s Jews.

There are two schools of thought. And get ready, I have a hot take about both of them.

The first school says, basically, that Jews in Muslim lands – aka Mizrahi Jews, as they’re now called – had it good. Its proponents point to the Jewish Golden Age in Muslim Spain, the high-ranking Jews of the Abbasid period, the wealth of Baghdadi Jews in the late 19th century, the influence of Moroccan Jews in the 1900s. And on and on and on. Look all this stuff up.

The second school of thought contends that the Mizrahi experience was largely negative; that antisemitism boiled just under the surface, ready to erupt at the slightest provocation. Its proponents point to Jews’ second-class status across the Muslim world. To the forced conversions in 12th century Yemen. To the 15th-century Moroccan massacres. To the Damascus blood libel of 1840. And on and on and on. Look all this stuff up too.

Ready for my hot take??

I think both are wrong. That’s right, I said it. I think there are people who genuinely and honestly believe each of these neat narratives, but I also have seen both been exploited by bad-faith actors eager to push an agenda. Because you know who loves to talk up the toleration and coexistence and high status and good treatment of Jews in Arab lands?

Anti-Zionists. Who are – all too often – antisemites. I mean, take this charming little screed from Cairo University professor Abdel Fattah Ashour:

“Jews throughout history received no better or kinder treatment than that of Muslims. The egoism and greed of Jews subjected them to persecution… They found in Muslims – merciful brothers who regarded them as fellow believers…”

That’s from 1968. Want to guess Professor Ashour’s opinion on the State of Israel? I’ll give you a hint: it’s not nice.

By promulgating the myth of idyllic Muslim-Jewish coexistence, Professor Ashour and others like him are pushing an agenda: to prove that Jews have no need for self-determination, because their lives under Muslim rule were hunky-dory. And if Jews have no need for self-determination, then how can they justify the existence of Israel?

Obviously, this is demented for many reasons.

But, on the other side, the folks who insist that Jewish life under Muslim rule was uniformly horrible? They tend to have an agenda, too.

In the words of Princeton professor Mark Cohen: “the harsh depiction of Jewish life in the Arab-Muslim world… cropped up in response to the Arab propaganda campaign against Israel… It gained further prominence as evidence of anti-Semitism in the Arab world mounted.” In other words, they’re overcorrecting.

I think this debate is silly, characterized more by political point-scoring than a sincere desire to understand history. Any student of history understands that stories are always more complicated than that. (Nerd corner alert: check out the TED talk by Chimamanda Ngozie Adichi about the danger of a single story.)

So I’m not going to reduce thousands of years of Jewish life into a story of “good” or “bad.” Because we judge whether something is “good” or “bad” by 21st century standards. That’s natural. We’re 21st century people. But concepts like “coexistence” or “tolerance” or “democracy” just didn’t exist in the pre-modern world. So when people point out that Jews in Muslim lands were treated as “second-class citizens,” they’re kind of right. But they’re also applying 21st-century expectations to a pre-modern world.

Jewish life in Muslim lands was governed by a hierarchy. At the top were Muslims. At the bottom were enemies of the Muslims. And in the middle were dhimmis, or the “protected people.” (I’ve heard it pronounced D-immis and Th-immis. I have no idea which is right, but I feel smarter saying Th-immis, so I am sticking with this one.) This category automatically included monotheists like Christians and Jews, and often stretched to encompass other religious minorities.

Dhimmis’ lives were governed by a document called The Pact of Umar, which was codified into Islamic law in the 9th century. Everyone should check out this pact. It basically set out a bunch of rules that dhimmis had to follow – the tax they had to pay, the clothes they had to wear, the social norms that placed them firmly underneath their Muslim neighbors.

In 21st century America, this would be wildly unconstitutional. But again, remember that concepts like “unconstitutional” or “democracy” just didn’t exist in the 9th century. The enforcement of the Pact was left to the discretion of the ruler. Which meant that the Jewish experience varied wildly depending on who was in power.

So rather than calling Jewish life in Muslim lands “good” or “bad,” think of it like this: throughout our history, Jews have been Other. Tightrope walkers, sometimes unaware of our precarious position, our eternal high-wire act. To be a minority in this context is to realize, one way or another, that your fortunes could shift with the next king, the next famine, the next political ideology. It doesn’t really matter what word you use – dhimmi, minority, Other. What matters is what happens when your society chooses to remind you of your Otherness. And that is the context of the Farhud – the 1941 Nazi-inspired riot that signalled the beginning of the end for Iraq’s ancient Jewish community.

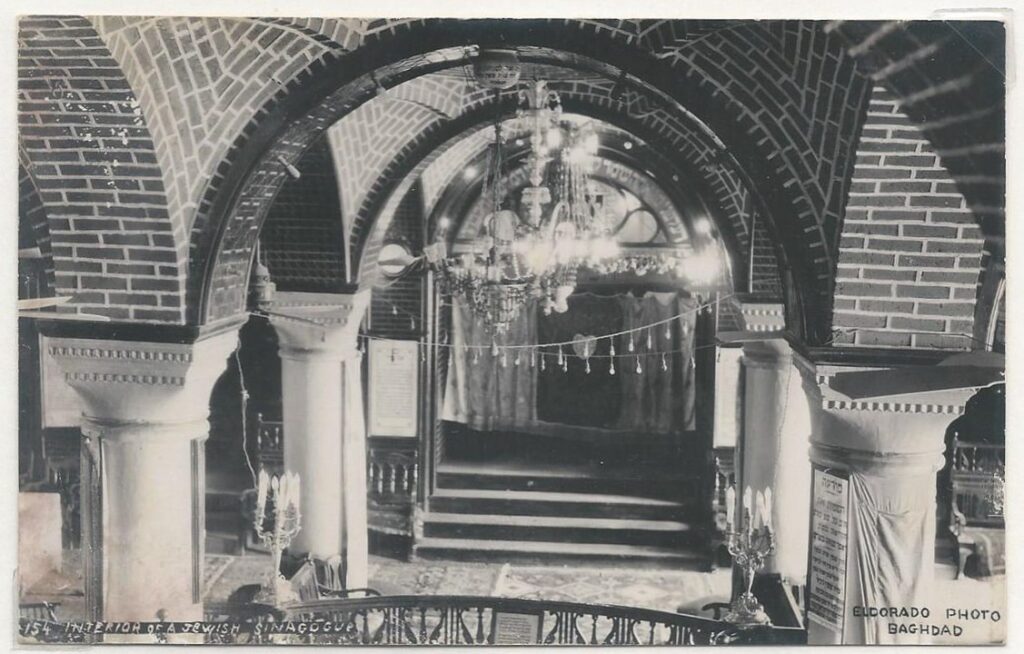

Story #3: An unlikely paradise

Because we have around 30 minutes and not, say, an entire semester, we’re gonna fast forward to the 1920s. You remember from our San Remo episode that the British barreled into the Ottoman territory of Iraq at the start of WWI. And though the Ottoman Empire wouldn’t officially dissolve until 1922, the British had no compunction installing Faisal I as king of Iraq in 1921.

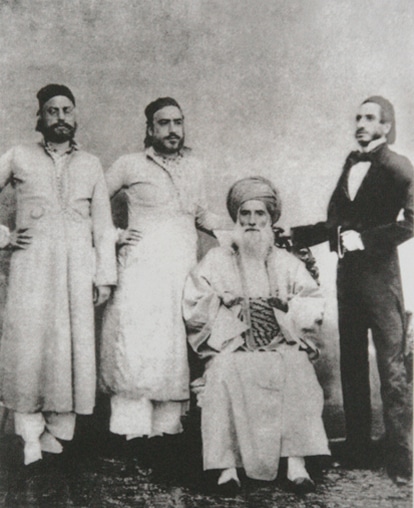

Faisal’s reign became known as Iraq’s Golden Age – at least, for Iraqi Jews. Which was fitting, considering that the country owed its existence to a Jew: Sassoon Eskell, son of India’s Chief Rabbi. According to a Times of Israel article published in 2016: “When Winston Churchill convened the Cairo conference in 1921 to discuss what would become Iraq, Jordan and Israel, Eskell was one of two Iraqis sent to determine the fate of his country and choose its king.”

And for about 20 years, things were pretty swell. My former professor Reeva Spector Simon writes: “nationalism in the new Iraq was supposed to be inclusive… Jews could identify with an Arab historical narrative that was not overwhelmingly Muslim. To them, Arab culture was their culture.”

Hand in hand, Jews and Muslims built Iraq’s culture. Here’s Jacqueline Horesh, who lived in Baghdad until 1966, describing her life in Iraq:

And here are Eileen Khalastchy and her sister Doreen, granddaughters of Hakham Ezra Reuben Dangoor, Baghdad’s Chief Rabbi:

But the thing about paradise is that eventually, you get kicked out. Every Golden Age has an expiration date. And by 1932, Iraq’s was coming to an end. King Faisal may have been personally tolerant of Jews and Christians and Shiites, and the Jews of Baghdad may have been well-connected and secure. But they did not account for the rise of Nazism.

Story #4: Nazis in Baghdad

The British Mandate in Iraq ended in 1932, making Iraq the sole independent country in the region. But before the Brits left, they managed to ensure that they – not the Iraqis – would control a significant percentage of the country’s oil.

And Iraq was not happy about this. The rage against the British began to simmer. And with it was mingled rage against the Jews, who, you know, had allowed the British to run roughshod over Arab lands. The Jews had helped the Brits install King Faisal, who was not Iraqi but Saudi! They had allowed the Brits to steal a significant percentage of Iraq’s oil! And perhaps worst of all, claimed the antisemites, the Brits and the Jews had worked together to seize Palestine from the Arabs.

But… why would Iraqis care about Palestine?

Well, for one, Baghdad was a hot destination for Palestinians eager to set up shop in an independent Arab country, who brought with them stories of thieving Zionists. Plus, Palestine was the region, where the third-holiest site of Islam was. And ever since the 1920s, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Hajj Amin Al Husseini, had been waging a highly effective antisemitic propaganda campaign all over the Arab world. (Check out our Hebron episode for more on that!)

By 1933, Husseini had found himself a powerful backer who could spread his lies even further: the Nazi regime.

Iraq quickly fell in love with Nazism. Radio Berlin broadcast antisemitic propaganda in Arabic. Gestapo agents wooed Iraqis with tales of British and Jewish depredations. And they weren’t above bribery, either: the Nazis made frequent use of cash and women to entice Iraqis to the dark side.

Here’s a clip from the amazing documentary Remember Baghdad, which is on YouTube.

“As disaffection with the British grew, the Germans promoted Hitler as a liberator, and in 1933 Mein Kampf was translated into Arabic. I met Shaul Menashe, who was a child in Basra. “There was a famous saying: God in the sky and Hitler on the ground.” (Recites saying in Arabic.) It sounds like a poem.”

Iraqi schools began teaching German. Iraqi youth movements borrowed heavily from the Hitler Youth. An Arabic-language version of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion made its way to Iraq. Thanks, Krushevan. (Don’t know who I’m talking about? Go back and listen to our Kishinev episode, which has too many parallels to this one for my liking!)

And as Nazism grew increasingly powerful in Iraq, Jewish rights began to erode.

It started with Jews being passed over for government jobs. Then layoffs of Jewish civil servants. Then quotas on import licenses. The writing was on the wall. From our vantage point in 2022, we can read it so clearly. We know what happens when Nazis come to town. We know that it’s just a hop, skip, and a jump from the loss of civil rights to the concentration camp.

But in the 1930s, Iraqi Jews did not know that. They thought they’d be fine. After all, many Jews hated the British just as much as their Muslim neighbors. Here’s Selim Fattal, who now lives in Israel, describing how he personally viewed the British: “I, and many others like me, the poor class, thought the British… you are robbing our resources. Our oil. And you are trying to tell us what to do. We don’t want any foreigners here. We want to rule ourselves by ourselves. Do not interfere. You have nothing to… go, go home.”

Similarly, the question of Palestine was not particularly pressing for most of Iraq’s Jews. While the Zionist movement gained some traction among Iraq’s lower-income Jews, the elites saw no reason to leave their comfortable homes to go farm in Palestine.

Iraq had been their home for the past 2,600 years. They had helped build the country’s cultural, financial, and political institutions. It was laughable to insinuate that they held multiple loyalties or that they were somehow not “real” Iraqis.

So as the propaganda got more vicious and the government more unfriendly and rights were chiseled away, Jews stayed, confident that all this madness would end soon.

They stayed when Zionism was banned. When Hebrew books and newspapers became illegal. When Hebrew teachers were expelled from the country. When Jewish schools were no longer allowed to teach Jewish history or the Hebrew language, for fear of fomenting “Zionism.” And as Reeva Spector-Simon writes: “Distinctions… between the Jewish religion and political Zionism began to blur, and Jews were requested to openly declare their loyalty to the Iraqi regime, which they did. ‘We are Arabs before we are Jews,’” they declared.

Not that these declarations of loyalty mattered. Jews were Jews. For that reason alone, they deserved to be punished. Here’s another clip from Remember Baghdad:

David’s aunt Eileen was a teenager when anti-Jewish attacks started happening nearby. “Once, my brother and myself, we went out for a walk on the riverside, and then a bicycle passed by. And suddenly I felt something hot on my back. It was burning, my dress was burning. He threw acid on me. Immediately, my brother tore my dress. It happened to a few girls.”]

By 1939, things were – and stop me if I sound too sophisticated right now – very, very bad. The Iraqi monarchy – led by Faisal’s young grandson – was nominally pro-British. But the King Regent who ruled in the young king’s stead walked a very fine line between the British and the hardcore Iraqi nationalists who had fallen head over heels for Nazism.

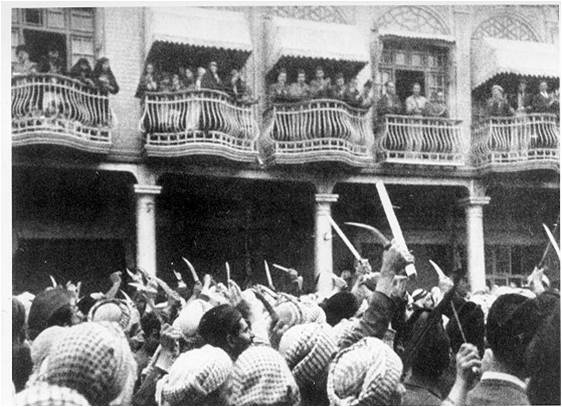

And in 1941, he was pushed off his tightrope when the nationalists drove out the royal family and seized control of the government. These pro-Nazi nationalists held power for about two months, until the British showed up, angry as heck that an oil-rich country might ally itself with the German enemy. So the British took back the country, leaving Baghdad in the hands of a “security committee.”

For Baghdadi Jews, this was a miracle. The British, and with them the pro-British King Regent, were coming back to restore stability! Soon, the anti-Jewish laws would be gone, and they could go back to enjoying their full and prosperous lives as Iraqi citizens. This return to normalcy coincided with the Jewish holiday of Shavuot, lending the festivities a particularly joyful air. But the Jews’ joy turned to horror on June 1, 1941.

I’m putting a trigger warning on this next section… so you can probably predict what happened next.

Story #5: The Dark Days

The British had taken back Iraq. But the pro-Nazi Iraqi nationalists weren’t going down without a fight. And if they couldn’t bring down the mighty British empire, they’d choose the next-best candidate: the Jews.

For two days, they sought to prove that though they had lost their coup, there was one group they could still kick around. Daniel Khazoom was eight years old during the Farhud. Nearly 70 years later, he cannot give his testimony of the riot without crying.

But not everyone was as lucky.

Historian Edwin Black writes: “Hundreds of Jews were cut down by sword and rifle, some decapitated. Babies were sliced in half and thrown into the Tigris river. Girls were raped in front of their parents. Parents were mercilessly killed in front of their children. Hundreds of Jewish homes and businesses were looted, then burned.” Honestly, reading that makes me so angry.

Steve Acre was nine years old in 1941, living in Baghdad with his widowed mother and 8 siblings. And his account of the day is gruesome. “Screams began to emanate from the house of [my] mother’s best friend… Later lots of men came outside and set the house on fire. And the men were shouting in jubilation holding up something that looked like a slab of meat in their hands. Then I found out, it was a woman’s breast they were carrying – they cut her breast off and tortured her before they killed her, my mother’s best friend, Sabicha.”

According to Professor Reeva Spector-Simon, “Through the first day of the Farhud, the regent and the British made no attempt to stop the violence.” Eventually, British forces restored order. But they could not restore the tremendous losses to Baghdad’s Jews. And the worst was yet to come.

Story #6: The Aftermath

The Jewish community in the region of Palestine were horrified by the news coming out of Iraq. But it was 1941. Reports of an unimaginable devastation were flooding in from Europe. And the British, who controlled Palestine, were being remarkably stingy with immigration quotas.

So while some Jewish Iraqis left for more hospitable corners – some to Palestine, some to India, some to Iran – most stayed put. And somehow, the rest of WWII left most Jewish Iraqis unscathed. It became easy for community leaders to rationalize the riot, to paint it as an unfortunate blip in Iraqi Jewry’s 2,600-year history. By January 1942, the community rebuilt itself, even going so far as to welcome Polish-Jewish soldiers fleeing Nazi-occupied Poland on their way to join British army. And when news of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising reached Iraqi Jews, they were so touched that they organized public memorials, wailing and cursing the Nazis.

But the normalcy wouldn’t last. After WWII, when the devastation of Europe’s Jews became clear, thousands of refugees sought entrance to Palestine.

And instead of feeling even a modicum of compassion, the Iraqis saw this as yet another example of greedy Jews taking, taking, taking. Let me rephrase that, because it’s so awful it’s almost hard to believe: at this point, the Iraqis were so antisemitic that they accused the Jewish community of making up or somehow provoking the Holocaust so they could justify stealing Palestine. As the UN geared up to vote on the partition of Palestine in 1947, Jewish life grew increasingly precarious. Pogroms began to punctuate ordinary days. The old blood libel reared its ugly, cliched head, claiming at least one life. Yet the Jewish Agency reported that Iraq’s Jews seemed determined to ignore the danger they were in, even as the government extorted their money and property.

When Israel declared independence in 1948, things really hit the fan. Azzam Pasha, the silver-tongued secretary-general of the Arab League, vowed that the 1948 Arab invasion of Israel – to which Iraq contributed troops – would “be a war of extermination and a momentous massacre.” But when Israel won, guess who the Iraqis took it out on? You guessed it, their resident punching bag, Iraqi Jews.

In June 1948, the Iraqi government dictated that “Zionism” would carry a prison sentence of seven years. Government agents swept Jewish homes looking for evidence of their Zionist sympathies; when they found none, they extracted confessions under torture, demanded financial compensation, and sentenced Jews to long stints in jail.

And though the Nazis had been defeated, the Iraqis were still borrowing from their playbook. They took away jobs. Froze assets. Boycotted Jewish businesses. Iraq’s wealthiest Jew was accused of sending cars to Israel, tried by military tribunal, fined $20 million, and hanged in his own courtyard, where a jeering crowd defiled his body.

No one was safe.

When a few thousand Jews managed to escape with a fraction of their money, the Iraqi government grew alarmed. Never mind that it had already crippled its own economy by turning its once-wealthy Jews into paupers and sending troops to fight against Israel. It focused on the assets of those Jews who had managed to flee with more than just the clothes on their backs.

Thinking himself clever, the Iraqi Prime Minister passed the Denaturalization Act, which – of course – applied only to Jews. As soon as a Jew left the country, they gave up their Iraqi citizenship. Their assets would be frozen, unable to be used outside of the country. And if a Jew registered to emigrate, they had to be out in 15 days.

The Iraqis figured they’d be getting rid of their poorest Jews – the undesirables, the drains on government resources. Instead, thousands upon thousands of Jews registered to GTFO.

There’s some debate about the exact number of Iraqi Jews in 1949. Some say there were over 150,000. Others, 130,000. But the most important number to know is that by 1951, roughly 120,000 Jews – 90,000 of whom lived in Baghdad – had registered to leave the country.

Which presented its own problems.

See, the traditional exit route involved sending Jews over the border to Iran, where they would wait in refugee camps until they could enter Israel. But the refugee camps quickly buckled under the strain of absorbing so many people. Plus, the overland route simply couldn’t handle the sheer number of refugees streaming out of Iraq.

So the Israeli Mossad teamed up with its old friend, Alaska Airlines, which had brought 49,000 Yemenite Jews to Israel between 1949 and 1950. Beginning in 1950, Alaska Airlines planes airlifted thousands of Iraqi Jews. But even working around the clock, the planes weren’t able to keep up with the sheer volume of Jews clamoring to get out of Iraq. And the Iraqi government was less than helpful. From showing up to the airport to abuse the departing Jews to dawdling painfully over the smallest bureaucratic details to threatening to send the remaining Jews to concentration camps, the Iraqis did everything they possibly could to make the exodus as difficult as possible.

But unlike their predecessors 2,500 years before, 20th-century Iraqi Jews were determined to make their way to Israel, no matter the cost. And the name of the operation that would get them there? You guessed it, Operation Ezra and Nehemiah, after the duo who enjoined Babylonia’s Jews to come back home to Judea in 536 B.C.E.

What a comeback tour.

But of course, the Iraqi government wasn’t going to let the Jews get away that easily. In 1951, they permanently and without warning froze the assets of all Jews who had registered to leave the country. To ensure that no Jew was able to access their assets before emigrating, the government cut the phone lines and closed the banks for three days. The Iraqi government stole hundreds of millions of dollars in today’s money in order to ensure that hundreds of thousands of now-penniless Iraqi immigrants would permanently cripple Israel’s already-strained economy.

It got worse from there. In March of 1951, the Iraqi government, eager to make life even worse for its Jews AND thoroughly destroy the Israeli economy, made two scary announcements.

One: it would stop issuing exit visas by May 1951. If a Jew wanted out, they had a limited window to leave. Tarry too long, and the chance to emigrate would disappear.

Two: Israel had until the end of 1951 to absorb every single Jew who had registered to emigrate. If Israel failed to take in the Jews who had registered to leave the country, the Iraqi government would send those Jews to a concentration camp. As you might imagine, this was a particularly effective – not to mention vicious – threat in 1951. So… Israel did it. By December of 1951, there were roughly 120,000 Iraqi Jews in Israel. Statistics vary about the number of Jews who chose to stay in Iraq after 1951. But all sources agree that fewer than 10,000 of Iraq’s Jews remained in the country. They would eventually leave too, sick of the unending fear and persecution. But that’s a story for a different podcast.

At the time, the Iraqis were delighted to get rid of the majority of their Jews. Even though, as Edwin Black reports: “Jewish firms transacted 45 percent of the exports and nearly 75 percent of the imports. A quarter of all Iraqi Jews worked in transportation… The controller of the budget was Jewish. A key director of the Iraqi National Bank was Jewish. The Currency Office board members were all Jewish. The Foreign Currency Committee was about 95 percent Jewish.”

In short, it’s not super surprising that today, Iraq totters on the brink of collapse.

And the Iraqis of 2022 are keenly aware of why that might be.

Edwin Shuker, who fled Iraq in 1972, returned to his birthplace in 2015. He reports, “There’s a dramatic change in the Iraqis’ attitude… They feel they’ve lost a valuable community and acknowledge that Jews were an important part of society there.” Other Iraqi Jews agree. Tsionit Fattal Kuperwasser’s Hebrew-language novel about the Jewish community in Iraq was translated into Arabic and became an Iraqi bestseller.

Her Iraqi friends tell her that: “the light went out on Iraq after the Jews were pushed out. That they want to rectify this injustice and bring [the Jews] home.”

But the feeling is not exactly mutual. A 2017 YouTube video shows a street poll of Israelis with Iraqi ancestry. Most say that they would be open to visiting the country of their parents and grandparents. But not a single one would agree to move back.

The first comment on that video reads:

As an Iraqi person, I am really sorry for what happened to you. My father and mother always told me how nice the jews in Mosul were.. I am sad you left…. Be sure that Iraqis don’t hate you. We love you and we always hear how nice Iraq was before you left…. we lost you, actually.

Iraq’s loss was Israel’s gain. Because while the flight of Iraq’s Jews temporarily strained Israel’s resources, the Iraqi community is considered one of the most successful Mizrahi communities in Israel.

They count among their number rockstars and novelists and professors, Chief Rabbis and Chiefs of Staff and many, many politicians. In fact, if you ask an Israeli for the dominant stereotype of an Iraqi Jew, they’ll tell you that Iraqi Jews are accountants and bankers and mathematicians. Which, as far as Israeli stereotypes go, is pretty innocuous.

Of course, stereotypes aren’t the whole story. And famous, successful Iraqis can’t represent an entire community. But for a community run penniless out of their home of over two thousand years, massacred and victimized and scapegoated, used as a pawn by hostile governments, the Jews of Iraq have done remarkably well in Israel and beyond. Their story is the Jewish story: they made the best of their exile until it was time to return home.

So that’s the story of the Farhud. Or rather, the six stories of the Farhud.

Here are your five fast facts

- The Jewish community in Iraq dates back to 586 B.C.E., when the Babylonians destroyed Jerusalem and carted off its Jews into captivity. By the time the second Temple was destroyed 600 years later, Babylonia – aka Iraq – was a center of Jewish life in the diaspora.

- Jewish life in Muslim lands was complicated, neither always good, nor always bad. One thing is clear: no matter where they lived, Jews were never allowed to forget that they were the Other, with a capital O.

- After WWI, Iraq became a British mandate. The British installed King Faisal, whose remarkably tolerant reign was known as the “Golden Age” for Iraq’s Jews. However, this came to an end in 1932, when Iraq officially became independent.

- Iraqi nationalists HATED the British, and soon fell in love with Nazism. When a failed coup in 1941 left Iraqi nationalists looking for someone to blame, they chose their Jewish neighbors. For two days, they murdered, raped, mutilated, looted, and destroyed Baghdad’s Jewish community. The toll was devastating.

- After the creation of Israel in 1948, life became intolerable for Iraq’s Jews. The government stole their money and threatened to send them to concentration camps if they weren’t out of the country by the end of 1951. Over two years, Israel absorbed nearly all of Iraq’s Jews, who have contributed hugely to Israeli society.

Those are your five fast facts, but here’s one enduring lesson as I see it.

Sometimes, I like to play what-if. Like, what if the Holocaust hadn’t happened? What would our world look like?

And I know I keep saying this, but as un-intuitive as it sounds, that question encompasses the Farhud. Because though it didn’t happen in Europe… though Germans didn’t do the actual killing… though there was no death camp, no partisans, no Nazi occupation… the perpetrators were stirred up by Nazi propaganda. Their victims were Jews. Historians make the explicit connection. The Farhud is a part and parcel of the Holocaust.

So imagine a different world, in which Faisal I’s vision endured. Where there were no Jews, no Christians, no Muslims. Just Iraqis. Where the Nazis never made it to Iraq, or better yet, where they never existed at all. What would the world have looked like?

Historian Edwin Black writes that the Farhud – and the subsequent dispossession of all of Iraq’s Jews – plunged Iraq into a disaster from which it has never recovered. In his words: “the rapid subtraction of Jews from the financial, administrative, retail, and export sectors was devastating.”

If Iraq had stayed democratic… if the Jews had been allowed to continue living their lives… Would Saddam Hussein still have clawed his way to the top of the Iraqi food chain? Would Iraq have lobbed 39 Scuds at Israel in 1991? Would it have gone to war with Iran? And would Iraq be in the state it is today?

It’s an impossible question to answer. But I’ll say this. The Arab and Muslim countries that expelled their Jews after 1948 cannot really be said to be thriving. I’m not blaming that entirely on the Jewish exodus, but I am pointing out a pretty clear historical trend.

Meanwhile, Israel – the only country in the world that was willing to absorb these refugees – is thriving. And I couldn’t be more grateful that these once-penniless, heavily abused refugees have a thriving home to go to.