Israeli historian Hillel Cohen makes a strong argument that, in fact, 1929 was the genesis of the Arab-Israeli conflict. This was the year that long-bubbling Arab resentment and fear of displacement burst into open, bloody revolt. The year that religious symbols took on a nationalistic dimension that would continue to spark a seemingly endless chain of conflicts. The year that all Jews living in Palestine (remember, that is what this area was indeed called then) – including Zionists and non-Zionists, Ashkenazi and Mizrahi – united with common cause.

And it started – perhaps unsurprisingly – in our holiest city: Jerusalem.

It is one of the sadder ironies of the Arab-Israeli conflict that we share so many of our holy sites. In the beautiful words of Palestinian intellectual and former president of Al Quds University, Sari Nusseibeh: “It’s remarkable how sacred sites that can arouse in us a sense of the ineffable mystery of life can also spawn a bare-knuckle brawl. This is a mystery only a metaphysician or a psychotherapist can make any sense of. I won’t try.”

This bare-knuckle brawl started because of the Temple Mount. If you’ve seen pictures of the Jerusalem skyline, you’ll remember the iconic golden dome that so strikingly catches the sunlight. That is the Muslim shrine known as the Dome of the Rock, which – along with the Al Aqsa Mosque – stands on the Temple Mount, named for the two Jewish Holy Temples that were once there. All that remains of the destroyed Temples is the outer wall of the Second Temple, known as the Western Wall, or the Kotel. Tucked into its stones are countless prayers scrawled on crumpled paper – the physical embodiment of two thousand years of prayer, longing, and tears.

But during the British Mandate, Jews had very little autonomy when it came to worshiping at our holiest site. Something as minor as adding benches so people could sit was tantamount to a declaration of war. So during Yom Kippur of 1928, a small and relatively innocuous action kicked off a firestorm of consequences. The Jewish community put up a mechitzah – a divider that separates men and women during Orthodox prayer. And though the barrier was only supposed to be up for 25 hours, it nonetheless infuriated the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem. The mufti had been appointed by the British and was basically the Arab community’s foremost legal and religious authority. (Think of him as roughly analogous to a chief rabbi.)

Unfortunately for the Jews of Palestine, the mufti was also a virulent antisemite. Maybe you’ve seen those pictures of the Grand Mufti cuddling with Adolf Hitler. Links are in the show notes. So the short-lived mechitzah was a delicious opportunity for him to reassert Muslim ownership of the Temple Mount. But when he demanded that restrictions be placed on Jewish worshippers, the British responded in a policy paper that while the Muslims owned the site, Jews were allowed to pray there.

Jews, 1. Mufti, 0.

So the Grand Mufti got creative, encouraging local Muslims to disrupt Jewish worship at the Kotel in any way they could – from launching construction projects nearby to holding unnecessarily loud religious ceremonies.

Honestly, I’d be laughing at this comically petty energy – except that it quickly turned deadly serious. Rumors, let’s call them conspiracy theories, began to circulate that the Jews, not content with their Wall, would come for the Temple Mount next. Proving that “fake news” is not a modern phenomenon, the Arab community circulated falsified pictures of damage to the Dome of the Rock, claiming that Jews had begun their campaign to destroy it.

Tensions seethed in the Holy Land… Until they erupted on Tisha B’Av, 1929.

Tisha B’av is the saddest day on the Hebrew calendar, commemorating the destruction of both Temples, along with a score of other historical tragedies… which made it a highly symbolic day for a protest about ownership of the Kotel. (Remember, the Kotel is all that remains of the Second Temple.) So a few hundred Jews marched to the Kotel, shouting “The Wall is ours!” and singing HaTikva, which would become the Israeli national anthem in just a few years.

As far as political demonstrations go, this was pretty tame stuff…Except for one thing.

Sari Nusseibeh writes that this was the moment that “the three thousand year long Jewish spiritual attachment to the Western Wall… turned into a nationalistic slogan, which in turn produced a nasty backlash among the Muslims.”

In his book Righteous Victims, Israeli historian Benny Morris expands on exactly what that means, explaining: “leaflets… were distributed by Husseini activists in nearby Arab towns and villages, enjoining them to attack Jews and to come to Jerusalem to ‘save’ the holy sites. One flyer… stated: ‘Rise up against the enemy who violated the honor of Islam and raped the women and murdered widows and babies.’”

Nusseibeh picks up on this thread. He explains that the day after the Tisha B’av procession, “Screaming ‘Islamiya,’ Muslims raided the Wall and tore up Jewish prayer books. Then a Jewish boy was stabbed to death after a quarrel on a soccer field.”

Soon, violence fanned out across the country.

The worst of it was centered on two ancient holy sites: Tzfat, or Safed, a city of mystics nestled high in the Galilee, and Hebron. We’re going to focus on Hebron, an ancient city tucked between the mountains of Judea, now commonly referred to as the West Bank.

Hebron is mentioned 87 times in the Hebrew Bible, and Jewish tradition holds that the four illustrious founding couples of Judaism – Adam and Eve, Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebecca, Jacob and Leah – are buried there, in a tomb known as Ma’arat HaMachpela, the Cave of the Patriarchs. After the Temple Mount, it is the second-holiest site in Judaism. And, if you’re keeping track of my son, Eyal’s Jewish education, it’s the first story he learned about in third grade Judaic studies. In Judaism, Hebron is kinda a big deal.

Still, in 1929, Hebron’s Jewish community, though ancient, was tiny – fewer than one thousand of the city’s 20,000 residents. Historian Tom Segev writes that the relations between Arab landlords and their Jewish tenants were “generally good.”

Yet he also recounts that as the Zionist community grew, so did Arab animosity. Soon, harassment, stone throwing, and even beatings became the norm, and the Jewish community made several, sadly prescient complaints “that the Hebron police force was not doing enough to protect them.”

But historians also agree that as news of the unrest in Jerusalem made its way to Hebron, the Jewish community was so confident that they refused to evacuate, or to accept Haganah protection – a decision that surely haunted them later.

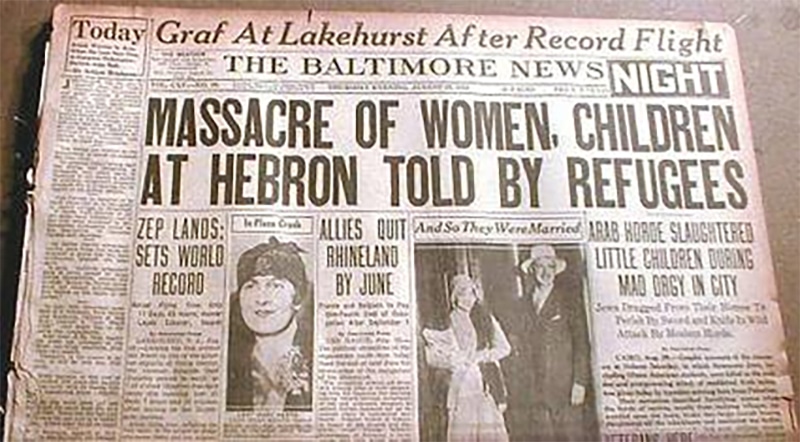

Newspaper accounts claim that the Jews were told that something was coming, with one reporting that “The Arab homeowners told their Jewish neighbors that today will be the great slaughter.”

The troubles began on Friday, August 23rd, as Arabs pelted people and property with stones. But things escalated quickly, and by 4 p.m., the mob had claimed its first casualty: 24-year-old yeshiva student Shmuel Halevi Rosenholz, stabbed to death outside the famed Hebron yeshiva. To add insult to injury, when he was buried later that day, the Hebron police – fearing that a large public funeral would only further arouse the rioters – limited attendance to six people.

As anxieties mounted, Eliezer Dan Slonim – a well-respected figure among Jews and Arabs alike – offered his home as a refuge to any Jews concerned about violence. Forty yeshiva students took him up on the offer – with tragic results.

Polish tourist Y.L. Grodzinsky, who took refuge in the Slonim house, later recounted that Shabbat morning service had just begun when he “saw several cars packed with Arabs bearing sticks, swords, knives, and daggers… As the vehicles passed the house, the Arabs spied the Jews and drew their fingers across their throats to signify slaughter.”

The brutality began shortly after.

As Grodzinsky later recounted: “The shrieks of the women and the babies’ wailing filled the house. With ten other people I put boxes and tables in front of the doors, but the intruders broke it with hatchets…. We…began running from room to room, but wherever we went we were hit by a torrent of stones… I looked out and saw a wild Arab mob laughing and throwing stones.”

Unfortunately, Slonim’s offer to take in yeshiva students had backfired.

See, as the manager of the Anglo-Palestine Bank and the son of Hebron’s chief Ashkenazi rabbi, Slonim was so well-connected that the Arab leaders of the massacre gave him an ultimatum. They told him they would spare all of Hebron’s Sephardi Jews if he just handed over the Ashkenazi yeshiva students hiding in his home. It’s a choice eerily reminiscent of the impossible calculus so familiar to us from Holocaust stories.

And I now need to give a bit of a trigger warning. For Slonim, the choice was clear. He refused and was shot on the spot, along with his wife and four-year-old.

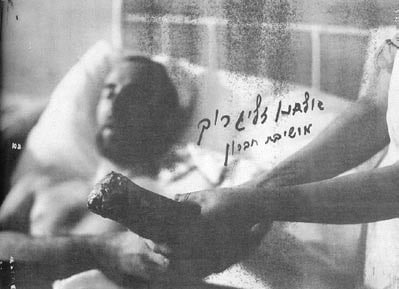

Grodzinsky, who along with a few others had survived the massacre by hiding behind a bookcase in the Slonim home, described the aftermath thus: “I could find no place to put my foot. In the sea of blood, I saw Eliezer Dan and his wife, my friend Dubnikov, a teacher from Tel Aviv, and many more… Almost all had knife and hatchet wounds in their heads. Some had broken ribs. A few bodies had been slashed and their entrails had come out.”

In a letter to the High Commissioner, survivors reported unthinkable atrocities: widespread rape. The castration of seven men, including rabbis in their 60s and 70s. A seventy year old tied to a door and tortured until he died. A two-year-old with his head torn off. A rabbi set on fire. An elderly disabled pharmacist tortured to death, his wife mutilated, his daughter raped and murdered.

There are many more eyewitness accounts I could share with you, and all of them are unbelievably brutal. But it hurts to talk about. And it hurts to listen. So suffice it to say: this massacre was ugly.

And yet, through the horror glimmered moments of humanity.

An American tourist named Aharon Reuven Bernzweig recalls that a neighboring Arab family protected him and 33 other Jews. “Five times the Arabs stormed our house with axes, and all the while those wild murderers kept screaming at the Arabs who were standing guard to hand over the Jews. They, in turn, shouted back that they had not hidden any Jews and knew nothing.”

Some of these Arab righteous gentiles saved Jews at great personal risk. Eliezer Dan Slonim’s sister Rivka later recounted the amazing story of the neighbor who saved her and her father: “The mob arrived at our house and we heard Abu Shaker’s voice: ‘Go away! You may not come here! You’ll have to kill me first.’ He was 75 years old, but a strong man. A man from the mob raised his sword and said: ‘I’ll kill you, traitor!’ Abu Shaker replied: ‘Go ahead and kill! There is a rabbinical family here, and they are my family.’ The sword pierced his foot, but he refused to move even after the mob had retreated. When we tried to bring him inside for treatment, he refused out of fear that they would return.”

Similar stories abound. Of the 550 Jews in Hebron that day, 67 were butchered. Roughly 130 hid, or pretended to be dead, or were lucky enough to live in homes left miraculously untouched. Approximately three hundred Jews were protected by 28 Arab neighbors.

Think about that for a second: 28 people saving 300. Neighbors protecting neighbors. In all this darkness, what a glimmer of potential hope for the Middle East.

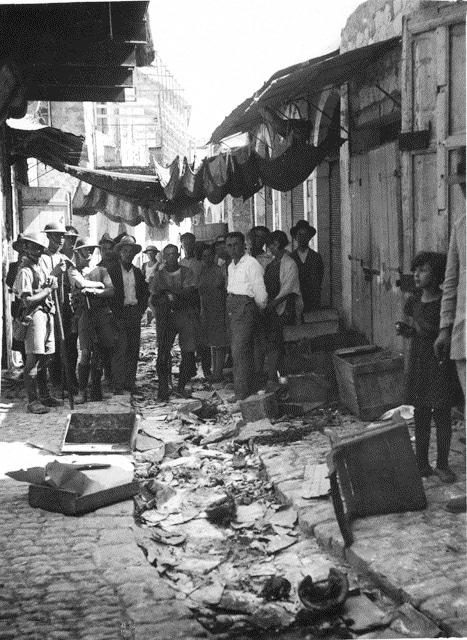

The Hebron riot ended at 10:30 that Shabbat morning – mere hours after it began.

But violence engulfed the region. During that week of terror – in Jerusalem, in Hebron, in Tzfat, in tiny towns in the Judean Hills – 133 Jews were murdered and 339 wounded. 116 Arabs were killed, mostly by the British… though there were reprisal attacks, too. Some Jews flouted the Haganah’s official policy of restraint and took matters into their own hands, killing several innocent Arab bystanders and, in one reported case, breaking into a mosque to burn books.

Among the casualties of the riots was an idea: the belief that the British were capable of protecting the Yishuv. Eyewitnesses reported that the British did little to stop the slaughter, and that even when the British tried to quell the rioting, they were painfully outmaneuvered and outmanned.

No, after 1929 it became clear that – even if they wanted to, which is highly debatable – the British were simply not in a position to act in the interests of Palestine’s Jews. High Commissioner John Chancellor warned London that the Arab world was awash in anti-Jewish propaganda. Should neighboring Arab countries invade Palestine to “help” their brethren in the fight against the Jews, the British would likely be powerless to stop them.

The British did not enjoy feeling powerless. In classic bureaucratic fashion, they sought to learn why the riots had happened, so they could formulate a coherent policy in response. The Shaw Commission – helmed by British jurist Sir Walter Shaw – considered the testimony of both Jews and Arabs before making its recommendation.

But as Arieh Avneri reminds us in his book The Claim of Dispossession, “policy in Palestine was not formulated solely by the British Government in London. The Mandates Commission of the League of Nations served as a kind of supreme supervisory body. Many countries were represented on this Commission, including members of the British Commonwealth, and winning their favor was a prime object of the political activity by both Jews and Arabs.”

Unfortunately for the Jews, the Arabs won this round.

In the words of American historian Naomi Cohen: “The Shaw Report… whitewashed the Mufti and the Palestine Arab Executive as well as the British officials in Palestine” and “criticized the immigration and land-purchase policies that, it said, gave Jews unfair advantages. The commission also recommended that the British take greater care in protecting the rights and understanding the aspirations of the Arabs.”

Here are three major takeaways from the Commission:

As the Commission put it “A National Home for the Jews… was inconsistent with the demands of Arab nationals.” In other words, the Arabs were very unhappy that there could someday be a Jewish state.

To the Arabs, the tide of Jewish immigrants represented an economic threat. Which brings us to takeaway number three…

As the report said: “A continuance of Jewish immigration and land purchases could have no other result than that the Arabs would in time be deprived of their livelihood and that they, and their country, might ultimately come under the political domination of the Jews.”

In short, as Naomi Cohen put it: “The Shaw report was a blow to Zionists everywhere.” Because the Commission recommended limiting Jewish immigration and land sales significantly, which had far-reaching results. For more on British immigration policy in Mandate Palestine, check out our Season 2 episode on Black Saturday.

So that sums up the relationship between the Jews and the Brits post-1929.

What about the other key player in this whole mess?

As you might imagine, the riots of 1929 demonstrated to the Jews that they could no longer rely on warm personal relationships with their Arab neighbors. It’s true that some Arabs saved and protected their community’s Jews. But thousands turned on them in an instant. This was painfully illustrated in thirteen-year-old Judith Reizman’s testimony about the Hebron riot, recounted here in a 1929 article from the Jewish Telegraphic Agency:

“When the Reizman girl had told her story in the breathless silence of the courtroom, the judge asked her if she could identify anyone… She calmly walked up to Ibrahim Abd El Assiz, a young Hebron merchant, her father’s next door neighbor, saying, “Yes, Ibrahim was nearest my father with a knife uplifted when the mob overtook my father.” Then addressing the Arab, who hung his head in shame, the girl asked him in the kindest voice imaginable, “Ibrahim, how could you?”

This last phrase – “Ibrahim, how could you” – heartbreakingly sums up the fractured relationship between Jews and Arabs in the wake of 1929. It was now painfully obvious to everyone – Jewish and Arab alike – that any common ground the two communities may have shared had just gone up in smoke.

This is why Hillel Cohen calls 1929 “year zero” of the conflict.

He writes “During the course of the riots, many – perhaps most – Jews and Arabs came to believe that they were caught in an unbearable, bloody conflict with each other, and this view became indelibly fixed in their minds.”

Beyond this, each side saw itself as the ultimate victim. Cohen writes that “in Jewish historical memory, the riots of 1929 became emblematic of Arab savagery, serving as ostensible proof that Arabs thirst for Jewish blood. At the same time, in the view of the Arabs, the disturbances were a legitimate national uprising.” Or, as Nusseibeh puts it in Once Upon a Country: “the mob, inflamed by an insanely simplistic nationalism, no longer made any distinction between Jews and Zionists. It was a black-and-white proposition: them against us. An awful precedent.”

This division was reflected in the hateful propaganda that swept the Arab street. Two weeks after the massacre, a British officer reported “a manifesto ‘full of falsehoods and inflammatory material which has been issued to Moslems in other countries.’” Yes, even in 1929, the power of “fake news” was strong: High Commissioner John Chancellor told the Colonial Office in London that: “The latent deep-seated hatred of the Arabs for the Jews has now come to the surface in all parts of the country. Threats of renewed attacks upon the Jews are being freely made and are only being prevented by the visible presence of considerable military force.” (By the way, for an episode that really delves into the power of “fake news,” check out our season 2 episode about UN Resolution 3379, and stay tuned for next week’s episode about the Kishinev pogrom of 1903.)

Keenly aware of their Arab neighbors’ vitriol, the Jews spent the remainder of 1929 getting serious about self-defense. It was hard to ignore the fact that other settlements, protected by the Haganah, fared better in the riots than Hebron and Tzfat, where the Jews were unarmed. Danny Gordis, Israeli historian, writes that in the wake of the riots: “The Haganah… transformed itself from an untrained military into a well-organized underground force. A Jewish army was beginning to develop.”

So too was the desire for revenge. While the Haganah itself preached restraint, its splinter groups – inspired by Ze’ev Jabotinsky – took the battle to the enemy. (For more on this, check out last season’s episode on Black Saturday. I’m telling you, check out that episode.) But these militias weren’t motivated solely by revenge. They had something to prove. They had to be intractable in order to build their country. Or, as Jabotinsky put it, they had to build an iron wall.

In his words, “There can be no voluntary agreement between ourselves and the Palestine Arabs. Not now, nor in the prospective future… The only way to obtain such an agreement is the iron wall, which is to say a strong power in Palestine that is not amenable to any Arab pressure.”

The 1929 riots broke the fragile trust between Jews and the Arabs, and we have never been able to fully rebuild it.

So that’s the sad story of the 1929 Hebron riots, and here are your five fast facts:

The 1929 riots were a turning point in Israeli history. According to Hillel Cohen, they represent the beginning of the Arab-Israeli conflict – the moment where both sides began to violently distrust the other, each building a narrative in which they and they alone are the victim.

The conflict erupted over religious symbols. Arabs feared that the Jews would encroach on their holy sites, while Jews demanded to be allowed to pray at Western Wall without restriction. Encouraged by the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, some Arabs published violent propaganda that encouraged ordinary people to defend Jerusalem from the Jews. Inspired by Jabotinsky, some Jews held a processional at the Wall during Tisha B’av, shouting “The Wall is ours!” Soon, the tension spilled over into brutal riots that the Mandate’s administrators were unable to contain. As Sari Nusseibeh reflects, this was perhaps the first time during the modern Arab Israeli conflict that the nationalist conflict took on a religious dimension, with both sides using their holy sites as emblems of their nationalist aspirations.

The bloodshed was especially bad in cities like Hebron and Tzfat, where the majority of Jews were unarmed, and entirely defenseless. The savagery was made all the more shocking by the fact that many of the perpetrators knew their victims personally. However, there were glimmers of humanity: roughly 300 of Hebron’s Jews were protected by their Arab neighbors.

The riots claimed 249 lives – 133 Jewish, mostly killed by Arabs, and 116 Arabs, mostly killed by the British. The riots made it very clear that neither the British nor the Arabs had Jewish interests at heart. Only the Zionist movement could save or protect them, and most of the Jews living in Palestine – Ashkenazi, Mizrahi, religious, secular, long-time residents and recent arrivals alike – united under the banner of Zionism. For their part, the Arabs no longer distinguished between Zionists and non-Zionists, Ashkenazi and Mizrahi, the immigrants or the locals who had lived in Palestine for hundreds of years.

Finally, the Shaw Commission, whose purpose was to investigate the riots, recommended changing the policy on Jewish immigration to Palestine, claiming that increased immigration, economic worry, and resistance to Zionism had spurred the Arabs to riot. British limits on immigration would have some far-reaching consequences on Israeli history. (Seriously, listen to our Black Sabbath episode!)

Those are your five fast facts, but here’s one enduring lesson as I see it.

Remember the start of this episode, when I told you that I disagreed with Sari Nusseibeh’s claim that the riots at the Kotel were the first time that Jews used their religious symbols for nationalist purposes?

Here’s why. I think that for all his insight, Nusseibeh misunderstands that Israel’s holy sites are inherently political. Our holy places and symbols played a nationalistic role for thousands of years before the modern concept of nationalism even existed – especially when outsiders threatened Jewish sovereignty.

Think about one example: the story of Bar Kokhba. Shimon Bar Kokhba was a military leader who led a rebellion against the Roman empire in 132 CE. And, he was briefly considered by the rabbinic leadership at the time to be the Messiah, sent to redeem the Jews. Why? He wasn’t a scholar or prophet. Why call him a Messiah?

Because the Jewish concept of the Messiah is inextricable from our ability to self-govern. The Tanakh is littered with references to the Messiah as a nationalist figure. And Rabbinic sources are even more explicit. As the medieval scholar Maimonides put it: The King Messiah will arise and re-establish the monarchy of David as it was in former times. He will build the Sanctuary and gather in the dispersed of Israel.

What I’m saying is, in Judaism, the religious and the political go hand in hand. Jerusalem has always acted as a symbol – not just of our religious faith, but of the seat of our nation. And throughout our many years of exile, Jerusalem represented our history of self-governance. After the failed Bar Kokhba revolt, the Romans barred the Jews from even entering Jerusalem. They understood the political power of religious symbols. A Jew who cannot enter Jerusalem is a Jew at the mercy of stronger nations. He is dispossessed. He is stateless. He cannot worship in his ancestral home.

So the 1929 devastation of Hebron wasn’t just political. As the Jewish people’s second-holiest city and the burial site of our foreparents, Hebron symbolizes our ancient connection to the land of Israel. After the riots of 1929, the city’s Jews fled in fear for their lives. The small community bravely re-established itself in 1931, only to be evacuated by the British in the wake of the 1936 riots. (Yep, more riots. Maybe we’ll cover them next season.) They wouldn’t be back until Israel’s miraculous victory during the Six Day War, in 1967.

And the first thing the Israelis who entered Hebron did? They went to Ma’arat Hamachpelah, “rededicating” it with a Sefer Torah. Because Jewish self-determination is inextricable from our ability to worship in our ancestral home. That has always been the case. It isn’t new. The 1929 riots simply made this painfully, heart-wrenchingly clear to the rest of the world.

This episode was produced by Rivky Stern. Our amazing team for this episode includes Adi Elbaz and Rob Pera. I’m your host, Noam Weissman. Thanks for listening, see you next week!