We’re curious…

With the release of a new film, “Farha,” on Netflix, and the passage of a new, pro-Palestinian resolution at the UN, the Nakba — and the story of Israel’s founding — is in the spotlight.

The “Nakba,” which means “catastrophe” in Arabic, is the Palestinian term for Israel’s establishment on May 14, 1948.

While Israelis celebrate Yom Ha’atzmaut around this time (on the 5th of Iyar on the Jewish calendar), Palestinians remember May of 1948 as the beginning of a 74-year-and-counting struggle to repossess their rightful land.

So, why is it in the news right now? The new film, “Farha,” by the Jordanian writer-director Darin Sallam, takes place in British Mandate Palestine in 1948. It includes a 15-minute scene in which IDF soldiers mercilessly execute a Palestinian family, including a baby.

The film’s opening credits say that it is “based on true events,” but it came under fire as being filled with historical lies.

Meanwhile, in a separate story, the UN just voted to commemorate the Nakba this coming year on its 75th anniversary, on Israel’s 75th birthday.

The resolution calls for “organizing a high-level event at the General Assembly Hall” in May 2023. It also urges the “dissemination of relevant archives and testimonies.”

The vote was 90 in favor, 30 against, and 47 abstentions. The countries that opposed it included Israel, Australia, Austria, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, the UK and the US. See the full results of the vote to commemorate the Nakba here.

The film and the UN resolution beg the question: What really happened in 1948? Did Israel expel Palestinians? Did IDF soldiers mercilessly kill Palestinians, as the “Farha” film tells the story? Here’s a recap of what happened, plus three key takeaways as we see it.

Diversity of perspectives

The Israeli-Arab activist Yoseph Haddad had this to say about “Farha”:

I saw the movie "Farha" and I can tell you that it is much worse than you think.

— יוסף חדאד – Yoseph Haddad (@YosephHaddad) December 2, 2022

The IDF soldiers are presented there as inhuman with unimaginable evil, all they care about is murdering and slaughtering without mercy (which is the exact opposite of the truth). >>> pic.twitter.com/QmBPVUWR9z

“This is a blood libel that will certainly increase antisemitism and incitement against Israel,” Haddad concluded. “If you haven’t canceled your Netflix subscription yet – do it now!”

According to the Jewish Chronicle, the Jordanian filmmakers “have a track record of inflammatory comments about the Jewish state.”

Last year, for example, the producer, Ayah Jardaneh, tweeted that “Israel is the real terrorist” and posted a “map of Palestine” that erased all trace of Israel. She also retweeted in 2014: “Hamas or his firecracker rockets is not a problem, but seven decades of Israeli brutality and oppression is.”

The release of the film on Netflix led “masses” of Israelis to cancel their subscriptions to the streaming service, Israel Hayom reported. Hundreds of thousands of people have also signed petitions demanding that Netflix remove it.

“Farha” and Netflix also drew condemnation from Israeli leaders, with outgoing Finance Minister Avigdor Liberman reacting: “It’s crazy that Netflix decided to stream a movie whose whole purpose is to create a false pretense and incite against Israeli soldiers.”

The creators of “Farha” condemned the “violent attack on the film” by Israeli officials and media.

“All the campaigning against Farha will not deter us from our goal which is to share the film and the story it tells with audiences worldwide,” the film’s creators wrote on Instagram.

They characterized the criticism as an attempt “to silence our voices as Semite/Arabs and as Women filmmakers, to dehumanize us and prevent us from telling our stories, our narrative and our truth.”

Meanwhile, with respect to the UN resolution to commemorate the Nakba, Israeli ambassador to the UN Gilad Erdan reacted on Twitter:

Today the #UNGA passsed a shameful resolution calling for an official event to commemorate the Palestinian “Nakba” on the 75th Anniversary of the creation of the State of Israel. By passing such an extreme and baseless resolution, the UN is only helping to perpetuate the conflict pic.twitter.com/RH3cHVWdT1

— Ambassador Gilad Erdan גלעד ארדן (@giladerdan1) November 30, 2022

In a speech to the UN delegates ahead of the vote, Erdan asked: “What would you say if the international community celebrated the establishment of your country as a disaster? What a disgrace.”

At the same meeting, the Palestinian envoy to the UN, Riyad Mansour, said to the delegates: “We are at the end of the road for the two-state solution. Either the international community summons the will to act decisively or it will let peace die passively.”

Mansour also condemned the 1947 Partition Plan, saying: “The plan was, and in many cases still is, to displace our people on their ancestral land.” He further claimed that there have been “75 years of Israeli policies aiming to uproot our people” since then.

Ted Deutch, CEO of the American Jewish Committee, also weighed in, tweeting:

On the day we remembered the 850,000 Jews who fled Arab nations following the birth of Israel, the @UN voted to commemorate the Palestinian "Nakba."

— Ted Deutch, CEO of American Jewish Committee (@AJCCEO) December 1, 2022

Not only does the UN ignore these stories, but it declares Israel's creation a catastrophe? Outrageous. https://t.co/sKrWjBcwWA

What does the Nakba mean to Israelis and Palestinians today?

In her book, “Israel: A Simple Guide to the Most Misunderstood Country on Earth,” Noa Tishby wrote:

“The Nakba is a branded term, used to attribute victimhood and heroism to a loss in a war that was initiated by that same losing side. If the Arabs had agreed to the U.N. Partition Plan, no war would have happened, no Nakba would have happened, and maybe we would have been living in peace ever since.”

The word “Nakba” itself emerged after a horrific incident in April 1948 that left as many as 200 Arab residents of the village Deir Yassin dead.

Despite certain details of the battle between Jewish and Arab forces still in dispute, what happened there on April 9, 1948 played an important part in the formation of Palestinian identity in the narrative of the Nakba.

Listen to our “Unpacking Israeli History” episode on Deir Yassin, which covers the incident in depth.

According to historian Benny Morris, “Deir Yassin had a profound demographic and political effect: It was followed by mass flight of Arabs from their locales.”

As of 2019, more than 5.6 million Palestinians were registered with UNRWA as refugees, of which more than 1.5 million live in UNRWA-run camps.

Today, the term Nakba is used often in Palestinian culture and is the theme of many popular books, songs and movies. Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish described the word as “an extended present that promises to continue in the future.”

Meanwhile, the Palestinian activist Raja Shehadeh, who lived under the Jordanian regime from 1948-1967, wrote that “The Nakba had effectively dismantled Palestinian identity,” adding that “Israel had succeeded in forging a national identity and Palestine had not.”

In his book, “Where the Line is Drawn,” Shehadeh recalled how the Jordanian regime suppressed Palestinian culture and identity:

“I grew up feeling only hostility toward the Jordanian regime. Even when I didn’t know what it meant to be a Palestinian, I knew I was not Jordanian. Meanwhile, the Israeli army was forging a national identity for the youth. I wished we had an army that could take the burden of having to create my own identity off my hands. How comforting it would be to have an institution like the military to mold our self-image and national identity.”

Nakba Day is marked on, or around, May 15th, the day of Israel’s declaration of independence on the Gregorian calendar.

In 1998, Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat proposed to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Nakba (prior to that, since 1949, there have been unofficial events marking the date).

Palestinians in Israel, the West Bank and Gaza, in Palestinian refugee camps in Arab countries, and in other places around the world mark the day with speeches and rallies. There have also been large Nakba Day demonstrations in New York City and London.

What really happened in 1948? Did Israel expel Palestinians?

The story of the Nakba is interwoven with the story of Israel’s independence. For the Jewish people, May of 1948 was a momentous occasion ushering in a new era of Jewish self-agency not seen for some 2,000 years.

That’s why this day is celebrated by Jewish communities around the world (and not just in Israel). But this was not the experience for everyone in the Middle East and its effects are still being felt to this very day in modern Israel.

Nearly 700,000 Palestinian Arabs either fled the area or were expelled before, during, or after Israel’s independence. So, what happened?

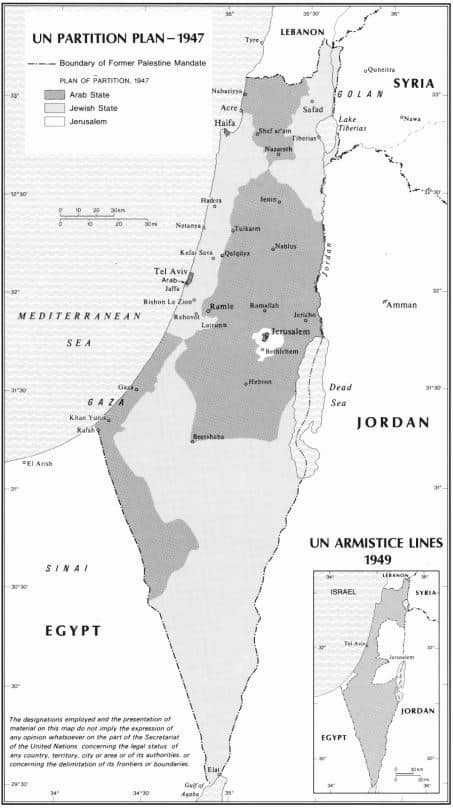

In 1947, the UN General Assembly adopted a Partition Plan, which called for both an independent Jewish and an Arab state in what was then British-controlled Mandatory Palestine.

The plan — Resolution 181 — was extremely detailed, as you can see in the map below.

Partition was hardly ideal for either people, as both states were left with vulnerabilities, separated territories, and Jerusalem — sacred to Jews, Muslims and Christians — designated as an international zone.

The Jewish leaders were conflicted about the partition proposal. In her book, “Israel: A History,” Anita Shapira explained (p. 85):

“Supporters saw it as the seed of an independent Jewish state, while for opponents it meant giving up the vision of the historical Land of Israel…Another group of opponents based their objections not on myth or history but on the rational argument that the partitioned Jewish state would be unable to sustain itself and to absorb and be a refuge for masses of Jews.”

But the proposal presented a real hope for Jewish sovereignty. Ultimately, the Zionists — led by David Ben-Gurion and Chaim Weizmann — accepted the plan. When faced with the best offer they’d gotten in millennia, they were not going to pass it up.

By contrast, the Arab leaders were united in their opposition to the plan. They opposed any territorial division that would give the Jewish people a homeland.

They also argued that the international community did not have a right to divide up land that the Arabs considered rightfully theirs.

Arabs launched a new wave of terror attacks on Jews, attempting to undermine the hope for stability promised by the Partition Plan.

Pan-Arabism reached a fever pitch, and the head of the Arab League, a coalition of surrounding Arab states, warned that partition would lead to “a war of annihilation.”

Even in face of these threats, on May 14, 1948, Israel’s provisional government declared an independent Jewish state in line with the Partition Plan.

The very next morning, seven surrounding armies invaded newborn Israel.

The remarkable turn of events is still talked about today. Jews successfully repelled the onslaught from the jaws of imminent destruction, but the repercussions of the invasion on both sides were devastating.

The chaos of war, along with the scramble to keep civilians safe, resulted in about 700,000 Arab refugees. There is scholarly debate over what exactly happened.

Some argue that Arab refugees left out of intense fear of the fighting, and some argue that they left on orders from Arab leaders to make way for strategic military operations.

It is clear that Israelis were directly responsible for the expulsion of tens of thousands of Arabs. Historian Anita Shapira wrote (p. 174):

In the first stage of the war, the Palestinian exodus from the areas assigned to the Jewish state was a consequence of the collapse of governmental systems in Palestinian society and the anarchy that reigned in their place.

In the second stage, following the Arab invasion, there were numerous instances in which the IDF expelled the Arab population and destroyed its villages to prevent its return.

The war was a matter of life or death, and the belief that Palestinians had caused this catastrophe hardened the hearts of officers and men who suffered harsh experiences of loss and displays of abuse by the enemy.

At a meeting of the provisional government on June 16, 1948, Moshe Sharett (who would serve as Israel’s second prime minister, for one year) addressed the issue:

“Had any of us said that one day we must get up and expel them all — it would have been considered madness,” he said.

“But if it came about during the upheavals of war, a war declared on us by the Arab nation, and as the Arabs themselves were fleeing — then it is one of those revolutionary changes after which history does not return to the [earlier] status quo.”

Meanwhile, in nearly every neighboring Arab country, civilian mobs directed their rage at local Jews who supported Israel’s creation. They committed waves of violence against Middle Eastern Jewish communities, some who’d been there for thousands of years.

About 850,000 Jews were forced out or relocated, and Israel absorbed nearly 700,000 of them.

Israel, whose total population doubled after the war, refused to allow back the 700,000 Arabs, either for demographic reasons or because many supported the invading Arab armies.

Adding to the tragedy, Palestinian Arabs were denied absorption into the surrounding Arab states that now hosted them, becoming forced refugees, a legal status still in effect for their descendants today.

According to Daniel Gordis, the new host countries “deliberately perpetuated their homelessness to foment international condemnation of Israel,” turning the Palestinian plight into a “genuine human tragedy.”

The difficult truth is that had those Arabs been allowed to return, Israel would not be able to be both a Jewish and democratic state, and it might have a hostile population within its borders.

Of course, no state could be built with a significant percentage hostile to its very existence. The 150,000 Arabs who stayed are now two million Arab citizens of Israel who make up 21% of the country’s population.

For Palestinian Arabs, their refugee status, the inability to return to their homes, and rejection by their host Arab nations sowed the seeds for deep bitterness toward the new Jewish state.

According to Shapira, the shock of defeat and refugeeism “further inflamed the myth of the return, perpetuating the refugee problem” (p. 175 – 176).

The Palestinian Arabs perceived “the 1948 war as an accident that would be swiftly rectified, since the demographic balance of power favored the Arab states and would enable them to triumph in the long term. This perception not only perpetuated the refugee problem but also was behind the refusal to make peace with Israel,” she wrote.

Since 1948, the Palestinians have rejected additional offers of statehood.

Three key takeaways:

- War is complicated and history is complicated. The film “Farha” is problematic not just because in this instance it is fiction, but because it lacks context. Did an IDF soldier really execute a Palestinian family, as the film depicts? We don’t know. We know that Deir Yassin happened. We know that there were also horrible atrocities committed by Palestinian Arabs during the war. “Farha” only shows the killing of a Palestinian family, with no context about the war or the invading Arab armies. We are in a media environment in which Israeli soldiers are already falsely presented as cruel and barbaric. In this climate, telling a story like this only adds fuel to the fire. It will increase antisemitism, misinformation, and incitement against Israel.

- We can empathize with the Palestinian perspective, while at the same time being passionate about Zionism and telling our own story. In his book, “Letters to My Palestinian Neighbor,” Yossi Klein Halevi addressed this poetically. Writing to his imagined Palestinian neighbor, Halevi explained the miracle of the Jewish people returning home “which I cherish as a story of persistence and courage and, above all, faith. But I could no longer ignore your counter-story of invasion, occupation, and expulsion. Our two narratives now coexisted within me.” We too can understand and empathize with the Palestinian narrative, while still maintaining love and pride in our own. We can be proud Zionists and Jews and understand a different side of the story.

- One of the best ways we can respond to films like “Farha” is with education. Just because so much of the world succumbs to propaganda, misinformation, and one-sided partisanship does not mean that we in the Jewish community should do the same. Instead, we should do the opposite of propaganda and indoctrination. Our best response is not “reverse propaganda,” but is education, exploring history in its full complexity with different perspectives. If more of us help educate about Israel, Israeli history and Israelis, then we will help people to be more critical consumers of films like “Farha.” Education won’t convince everyone, but it is a critical part of the fight against misinformation and hate.

Originally Published Dec 6, 2022 10:11AM EST